Ernest Hemingway first arrived in Valencia in the summer of 1925, following bullfighting legend Cayetano Ordóñez from Pamplona, with the intent to keep “the party going,” so to speak. He found himself in the center of the city at the Hotel Reina Victoria, with a balcony that gave him a panorama of the bustling town below. He was enamored. “In Valencia, it's damned stupendous at the beach or in the city to eat a melon washed down with a real cold jug of beer,” he wrote, and in that spirit, began his first novel, The Sun Also Rises, on that same balcony. Hemingway, the master of short prose and vivid precision, was nevertheless possessed with an eye for the grand view, a sweeping insight regarding his time in Spain. So immersed in the atmosphere, he wrote while absorbing the surrounding cultural noise. I arrived in Valencia during the 19-day Fallas festival, culminating in what I’d define as a riveting travel week, where I couldn’t help but dream of my favorite writer, his history, and imagining where he might have luxuriated over a cold beer on a warm Valencian evening.

I, too, stayed at the Hotel Reina Victoria, overlooking Plaça de l'Ajuntament and the main Fallas sculpture of the great Valencian street artist, Escif, whom I am here to visit and share in his landmark project. To put it mildly, the annual Las Fallas of Valencia is idiosyncratic, irreverent, and wonderfully serious. Fallas, historically, stems from an old carpenters’ tradition of celebrating the arrival of spring by burning their leftover and unused materials in the street as a sort of ritual of rebirth and the dawn of a new season. Every year from March 1 through 19, the city now bubbles with the energy of over 400 fallas built around the city, commissioned by neighborhood districts, and resulting in towering monuments of animated commentary. Closing out the ceremony, they are all ignited into burning symbols, a clearing before the start of spring, which encourages a friendly bit of ruckus among the hundreds of thousands of people swelling the city. This, too, is a dichotomy; massive fires burn around the city in what sounds and appears to be destruction and yet represents rebirth.

I arrive in Valencia in the early afternoon and am escorted directly to Escif’s work, an experience I found to be an almost mea culpa of the pandemic’s effect on our lives. I was supposed to visit in 2020 for this same purpose, to see Escif’s work go up in flames, though, of course, it was canceled, and yet in 2024, Escif was the city’s selection once again.

In front of the Ajuntament de València and to the left of the Font de la Plaça de l'Ajuntament, tower two white doves, symbols of peace, fight over, or carry, what appears to be an olive branch to the skies above. Or is it being brought down to earth? Are the birds being held down by these multi-story wooden structures to which they’re bound, caged, and unable to escape? Surrounding this struggle are a series of cartoonish, pop-cultural, political, and universally-reflective sculptures, slightly larger-than-life but not quite so intimidating.

All these elements are jarring, contradictory, and almost feel random. Walking through the square, teenage girls and adult women wear traditional regalia, a mix of centuries old dress and hair styles that could be the past and future in conflation. Overhead, a booming fireworks display, here known as a “mascletà,” pounds both the mind, ears, and heart as rhythmic explosions create an atmosphere of controlled chaos and celebratory elation. The decibel level reaches near 120, testing your ability to make a clear decision about what you’re seeing and hearing. Your heart vibrates. Your teeth ache. Your eyes shake. It’s 2 p.m., and the mascletà lasts five minutes, yet the energy lasts for hours. There's a contradiction between joy and violence that is unexpected to the senses. There is the sound, the sights, and there is this fury.

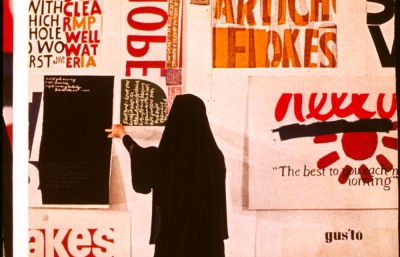

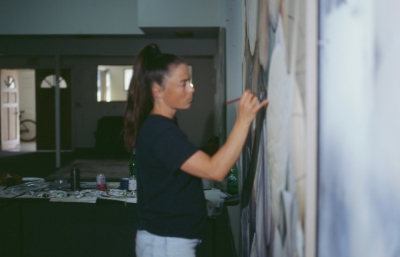

Knowing how Escif has made work over the years, whether illegal street pieces, murals, or his paintings and drawings, part of me thinks that this delay for his Fallas was more poignant.. The war in Gaza, for which Escif and his team started the Unmute Gaza project in late 2023, is evident even though works were planned before the war began. Escif likes to have the viewer think about the malleability of truth and opinion, where contradiction is part of Western life no matter how well-intentioned. At the heart of this installation, two doves of peace fight over an olive branch, and together, go up in flames. When I spoke with Escif about this, standing beneath the doves as the final positions for surrounding sculptures were being mapped, he spoke about worldwide tension and the omnipresent forces of good, noting later, “Two doves, one branch. War implies selfishness and rejection; peace implies empathy and acceptance. War separates us; Peace unites us. Fear and Love. Two peace doves fighting over an olive branch.” I couldn’t help but think of the famous line from Mexican poet and academic César A. Cruz when he said, "Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable." Escif does just that.

Again, dichotomy. In Valencia, I found the romance of its historic city center, swirling with the distant smell of cigarette smoke mixed with the sweet scent of orange blossoms in the air. The clinking of beer glasses echoes amongst the winding streets, intense conversation from outdoor tapas bars. Brutalist architecture intersects with the Baroque. After experiencing the booming mascletà, I enjoyed the expected: paella and a half-pint (or two) of beer. Our host, David, took us to Casa Baldo, an indoor-outdoor cafe that probably hasn’t changed since its establishment in 1915. The atmosphere is noisy, lively, and fun, as if the city is fully synchronized with the Fallas buzz. I’m fully into it, consumed in absorbing so much time thinking about Hemingway and his love for this city, and David says the magic words: “Let’s go to the museum.” We head to the IVAM (Institut Valencià d'Art Modern—Valencian Institute of Modern Art), which is adorned with an Escif mural on its large back wall, and features a beautifully brutalist interior. The museum is home to an incredible collection of works by modernist sculptor Julio González, a man who pushed iron to its limits. The IVAM was designed by Carlos Salvadores and Emilio Jiménez as the first modern art museum in Spain, and though only built in 1989, it has its own unique place in the city’s old quarter. We close the night at a wine bar, Boucan Winebar, and, once again, I can’t help but hear the distant echo of Hemingway when he wrote that "Wine is the most civilized thing in the world.” It’s all true in this moment.

The next day solidified this feeling I was having about Valencia, that it is a city that has been rewriting chapters of itself for nearly 600 years, although no eraser has ever quite wiped the page clean. All at once, there is a vision of past, present, and future possibilities. We take a bike ride through Parque Central, past the ancient 14th century city gates of Torres de Serrano, and into a complex known as the Ciudad de las Artes y las Ciencias, which could only translate to “spaceship from the distant future has landed to host the arts and sciences," if I didn’t know any better. Designed by Santiago Calatrava, the structures feel like their own city, and riding bikes through the architectural marvels I feel like a scene from That Man from Rio. This creates our next contrast as we head towards Casa Montaña, a tavern founded in 1836 that has many of the same qualities as its original state (including the wine cave) and lies in the center of Cabañal district, a working class neighborhood where many of the homes have been passed down through families for generations. The story goes that years ago, the city government attempted to extend a major thoroughfare to the beach, straight through the heart of Cabañal, thus displacing many local residents rather than the desired high-rise condos that would benefit big business and the gentrification of one of the city’s unique neighborhoods. The residents protested, organized, resisted, and, thankfully, won. This is the rare place in a city that preserves, discusses, and honors its history. “What is a city? What are its traditions?” if something like this is demolished. There is always the fine line, to not hold onto the past with an iron fist, while not fully eradicating the character of a place. A city shouldn’t fully erase itself from itself.

Perhaps my understanding was taking shape. We end the day back in the old city center at the Hortensia Herrero Art Centre, a newly opened museum in the midst of the ancient city infrastructure. The space houses Herrero’s sprawling collection in the former Valeriola Palace, one of the city’s oldest buildings, intertwined with ancient Roman, Jewish, and Islamic history. A part of the city’s DNA reconstructed, integrated, and honored.

The next day was a whirlwind of experiencing a city’s history and embedded identity. We started at the beautiful, bustling Central Market with brunch at Ricard Camarena’s Central Bar, then head to the nearby Silk Exchange, the historic economic center of the city. Here, orange blossom fragrance wafts through the area, a lingering reminder of some distant past. We wandered to the CCCC (Contemporary Cultural Centre of El Carmen), a former convent now housing contemporary art, highlighting Felipe Pantone’s newest exhibition, his op-art sculptures in perfect synchronicity as distant 2pm mascletà explosions provided an echoing soundtrack. As we head to the Ruzafa neighborhood for a late lunch of paella at Los Madriles, the buzz of Fallas is in full-force, with Valencians spilling out of every tapas bar and firecrackers almost rhythmic in their intensity. It had become a drum-beat for my heart.

As the trip was coming to an end and Escif’s work would go up in flames, as the distant sounds of pyrotechnics celebrated a place so ancient, I thought about how much life a city possesses, like the spaceship architecture that lies within eyeshot of the ancient city gates or the man playing a version of “Bohemian Rhapsody” on his flamenco guitar. I wonder what song Hemingway would have heard on that same street 100 years ago. We pass “Free Palestine” tags near the site of old Roman ruins. The hotel where Hemingway began his famed career now sits across from a Taco Bell. The past and present continue to collide wherever you look, but it is the preservation of this city’s infrastructure, and the hope that this can remain, that is of such vital interest for both residents and visitors. How can our past, present, and future co-exist? Do history and progress cancel out harmony?

In the end, two doves burned to the ground on March 19th, each symbolizing its version of peace and going down in flames in unison, becoming one. Mutually assured destruction. As Escif wrote of the piece, “La paz se alimenta de la unidad—Peace is fueled by unity.” It was a concept, created by an artist at the height of his powers, full of sound and burning with fury, signifying almost everything. —Evan Pricco

Thank you to David Arlandis and Visit Valencia for hosting Juxtapoz in Valencia, and Chantal for the bike tour around the city. This article was published in the SUMMER 2024 Quarterly.