On Thursday, November 7th, rodolphe janssen gallery in Brussels presents its third solo show with NYC-based artist, Sean Landers, whose work explores the role and psyche of a contemporary artist, showcased through three distinct groups of paintings.

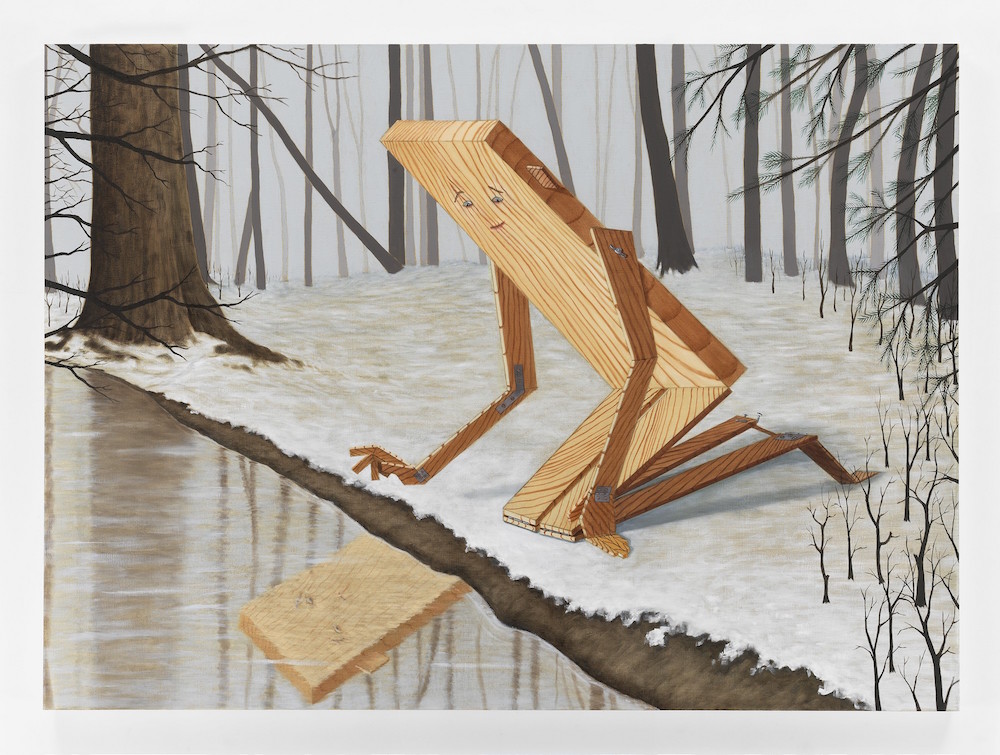

Over the course of a three-decades-long career, Landers has developed several singular series of work where he re-examines the relationship of the artist to their work. Arguably most recognized of them is a simple character devised from the materials which support a canvas. Sparked by a strong interest in Rene Magritte’s 1947-48 La Période Vache, Plankboy's birth and surreal experiences infuse the struggle of artistic endeavors and the odds which must be overcome in order to continue to create. This time around, he becomes the subject of Greek mythology, in pieces that inform an aspect of the artist's personal or professional life. The motif of wood grain as the core base of the work imbues the other series of work, such as smaller figure-based pieces and, more notably, the large-scale paintings that honor old-fashioned wooden signage.

Curious about the results of Landers's most recent exploration, we ventured to the artists' studio to learn about the new adventures of Plankboy, his relationship with Greek mythology, and possible concepts for future work.

Sasha Bogojev: What made you bring back and further explore Plankboy?

Sean Landers: I love him and I wanted to be in his company a little more. He is like a more pure and sincere me. In these troubling times, it is nice to have him back. He is innocence, like something made by a kid. I try to make his construction feel innocent, similar to how I would have constructed a go-cart when I was eight years old.

How much do you think he, or your relationship, changed since the first time you painted him 20 years ago?

When I first made him, I was thinking about not fitting in. He is a piece of milled lumber in a forest of natural wood. Kind of like an American returning to a country of their ancestry. It’s kind of how I feel in Europe. Now, he is a known character in my art, and I can put him into known stories, such as these myths.

How did Greek mythology come into the picture and do you have plans to further explore this concept?

I have used Greek myths pretty regularly throughout my career, in all of my different mediums and series. I’ve used them in writing pieces, videos, sculptures, and several different painting series. Greek myths, Greek art, and Greek drama are the basis of western civilization. The meanings are so universal that everyone understands them immediately, yet every artist who picks them up can add their unique spin. Kind of like a musician performing their rendition of a great piece of music.

Also, on a personal level, I am part Greek. My grandfather was born in Greece, and I like that connection to it, as well.

How are his "new adventures" metaphors for your personal experiences, and is that part of an effort to be honest about your work?

Yes, very much so. Let’s talk about each of them:

Narcissus is metaphorical for all people who devote their lives to making art. Anyone who believes that what they make in their art studio is worthy of attention and acclaim is inherently narcissistic. Here we have Plankboy smiling at a reflection of himself frowning back.

Pygmalion makes sculpture so beautiful that he falls in love with it. Artists do that with nearly everything they make, at least I do. Here we have Plankboy, so ostensibly lonely in the forest, he doesn’t quite fit into making a partner or companion for himself.

Sisyphus struggles to push the boulder up the mountain, only to have it roll back down. And he has to repeat this for his entire life. This addresses the Groundhog Day-like aspect of life itself. For me, this is making paintings and shipping them out, I suppose. It’s funny to see Plankboy do this with his impossible body and flimsy construction.

Daedalus, I assume most people will see this painting as Icarus, and that’s fine with me. For me, though, I like seeing this one as Daedalus because I have two kids who are young adults and just taking flight in life, and I see the world now more as a worrying father than I do as a dreamer daring to fly too close to the sun. I used to feel that way when I was young, but I’m 57 now, and it is definitely Daedalus time.

What is it about Magritte’s Période Vache that has challenged and inspired your practice for so long?

Magritte’s Période Vache symbolizes artistic freedom for me. I have made my freedom to go anywhere and to do anything central in my practice, and this one series by Magritte encapsulates that impulse to be free better than anything else I’ve ever seen.

Période Vache is central to who I am. I want my whole life to be one decades-long Période Vache.

What is the background of the wooden signage pieces and from where is the text derived from?

They emerged from three different series twisted into this new one. Most basically, it is Plankboy made into signage. I also want to paint Plankboy covered in text – coming soon. It also incorporates my writing, which is the foundation of my artistic practice, and it blends in the stripe paintings, which I recently brought back to life as my bookshelf paintings and have now evolved into these new sign paintings.

I will always find new ways to combine aspects of my older series to create new directions, and I will always incorporate writing into painting. These signs are my newest way of doing it.

Speaking of combining aspects of work, do you see The New Englander as another iteration of Plankoboy? What is the background of that piece?

I like to twist my different series together to create new ones. With The New Englander, I am combining my 1995 Hogarth series with the wood grain to start a new direction. This tangent has just begun, and I don’t yet know how far or how big it will become. But I like where it’s going so far.

Studio photos courtesy of the artist

Photo credit: Christopher Burke

Individual work photos courtesy of the artist and rodolphe janssen, Brussels