Nature has been an inspiration for art since the dawn of expression. Looking back through history, every culture attempts to portray the human relationship with the natural world, from the ancient cave paintings at Lascaux to the hand-painted pottery of ancient Greece. In the case of artist Summer Wheat, who lives and works in New York, reconnection with her rural past permeates her practice.

Born in Oklahoma City, Wheat was introduced to art through Native American weaving and craft. Now, nearly 20 years into her career, she creates massive frieze-like paintings that serve as mythologies in the worlds she constructs with story-telling at the core. Neolithic paintings weave symbology from Native American art, Japanese printmaking, and Greco-Roman vase painting into a narrative. With striking visual language, Wheat's paintings loom over with explosive shapes and color in a loose style of dense composition.

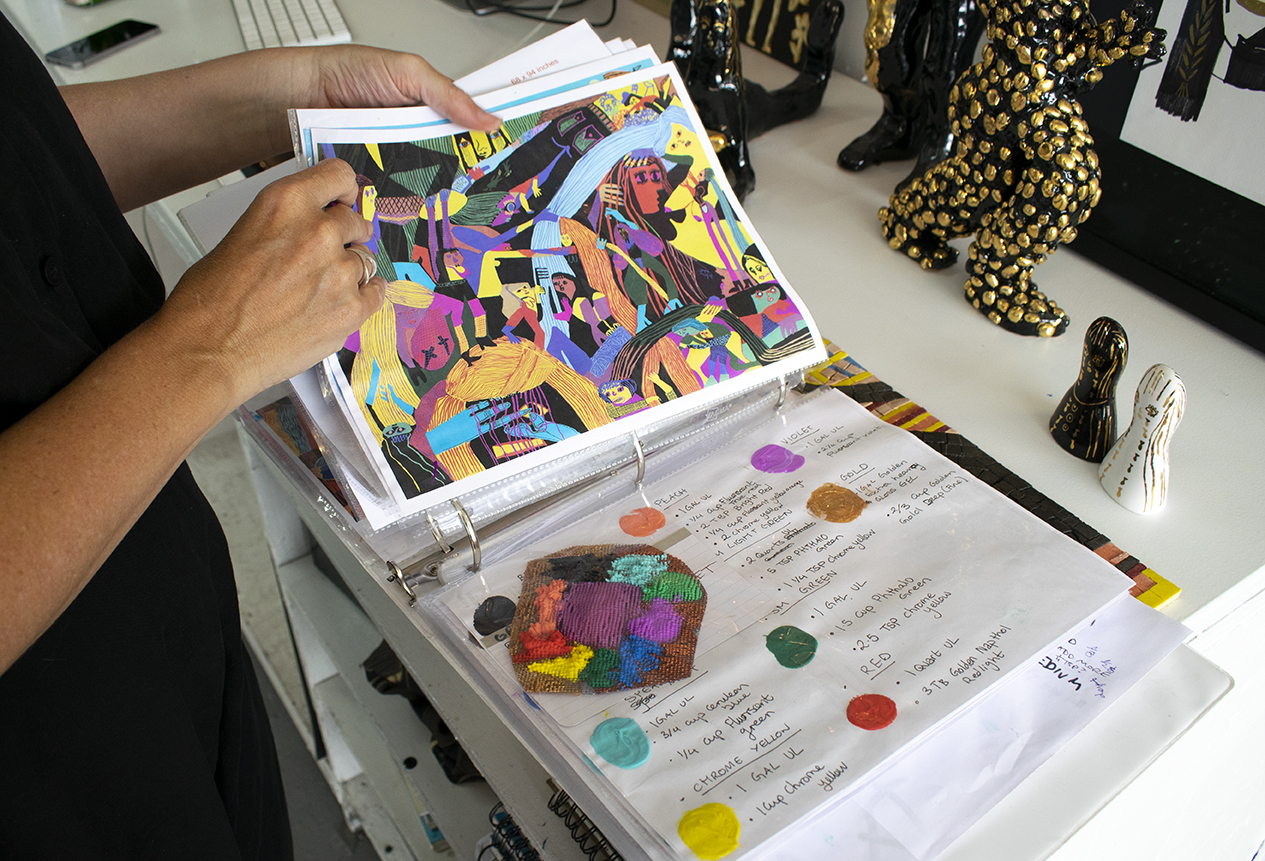

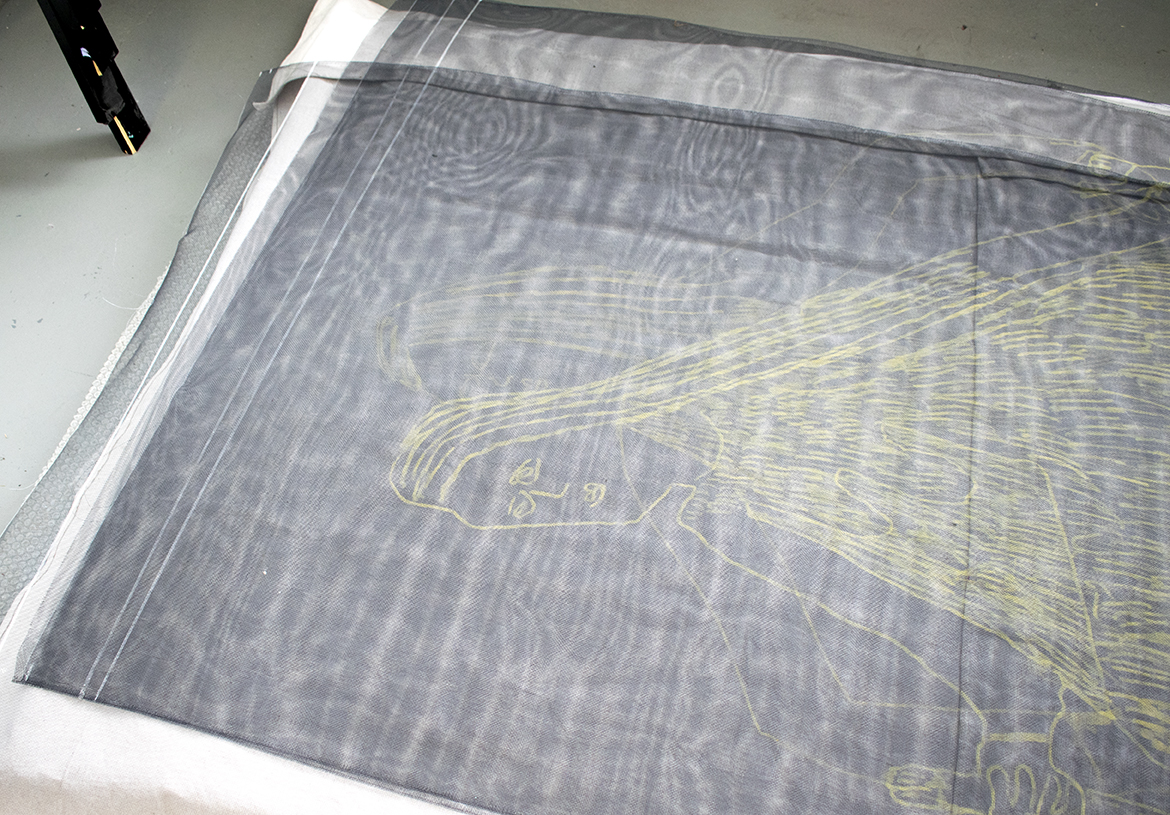

Wheat employs a unique method by extruding paint through aluminum mesh sheets to create a stippled, pixelated effect similar to weaving. Using strategic line work and bold, contemporary color palettes, Wheat's paintings evoke medieval tapestries and historical tableaux, lush with meaning. Figures engage in a variety of activities, hunters, gatherers, fishers and farmers, each subject communing with the natural animal kingdom in a variety of ways.

Textural and playful, Wheat's paintings vibrate, eliciting an elemental response. Adopting traditional male roles, Wheat's women vibrate with nativity and emotional energy, rewriting the history of our collective past. With art history at her back, she recasts stories through a contemporary lens and presents an alternative record, both accessible and venerable. I sat down with Summer Wheat to discuss her work, her life outside Oklahoma, and the influences that have shaped her own personal relationship to nature.

Jessica Ross: Your work has steadily become more and more colorful over the past few years. What changed?

Summer Wheat: Using a lot of color is not necessarily new for me—I used a lot of color in my early work. But in 2016, I took an intentional break from using color to better focus on the shapes in my work. I wanted to make paintings that were like sculptures, paintings where the lines of my drawings could become three-dimensional. Once I developed a technique for doing that, I worked on building a new relationship with shape. To do that, I broke down the paintings into limited color palettes, using mainly black and white, with small additions of color. I needed to discover how the shapes in my paintings related to one another before moving back to using bold color.

Do the amped-up tones in your recent series speak to the subject of the work?

I do choose a palette of colors that I feel connects to the subject and theme of the work, yes. But usually, the choice of tones has more to do with the mood I'm in at the moment. My color choices spring from a wide variety of influences, such as those found in fashion, through travel, or from my own intuition.

Can you talk a bit about your influences from art history and how these elements from different cultures populate your visual lexicon?

I grew up in Oklahoma, so my first exposure to an art tradition was seeing and learning about Native American art. I didn't have a formal introduction to Western art until after I graduated high school. In school in Oklahoma, the magazines and reference books in art class were mostly either Native American or comic books. I think the connections I built during my formative years to the language found in those works means that I tend to seek out and be particularly open to imagery that is outside Western art tradition.

You've dabbled in everything from painting to jewelry, ceramics, textiles, and tile work. Is there any medium you're dying to dive into next?

I would love to design a pair of sunglasses and a collection of marzipan.

What are some of your favorite aspects of collaboration, and what are most challenging?

The challenge and the joy of collaboration is all the hard work you have to do to get everyone on the same page. That process of trying to integrate different perspectives is often long and delicate, but the opportunity to create a work that is the product of those conversations—to see those conversations come to life in a piece of art—makes it worth it.

Your large works radiate narrative on a massive scale, the same way a biblical tapestry or marble frieze would. What is it about prehistoric visual modes of story-telling that you find so appealing for your work?

Growing up in Oklahoma, I felt outside the knowledge base of Western art history, so I often connect most deeply with art that is prehistoric or could be considered outsider art. Much of Western art is bound to postulations of refinement—I'm drawn to traditions that work outside those modes. When I see a sculpture or artifact from an ancient era, I feel relief. I feel that it's coming from a place that I'm trying to reach. I love art objects that embody a sense of humor and freedom of form. Though these reference points don't make up the entirety of my point of view, they are often at its core.

Noting your impeccable, organized studio, and how your process is laid out, I wonder if you leave room for spontaneity? How often do you deviate from an original sketch or design?

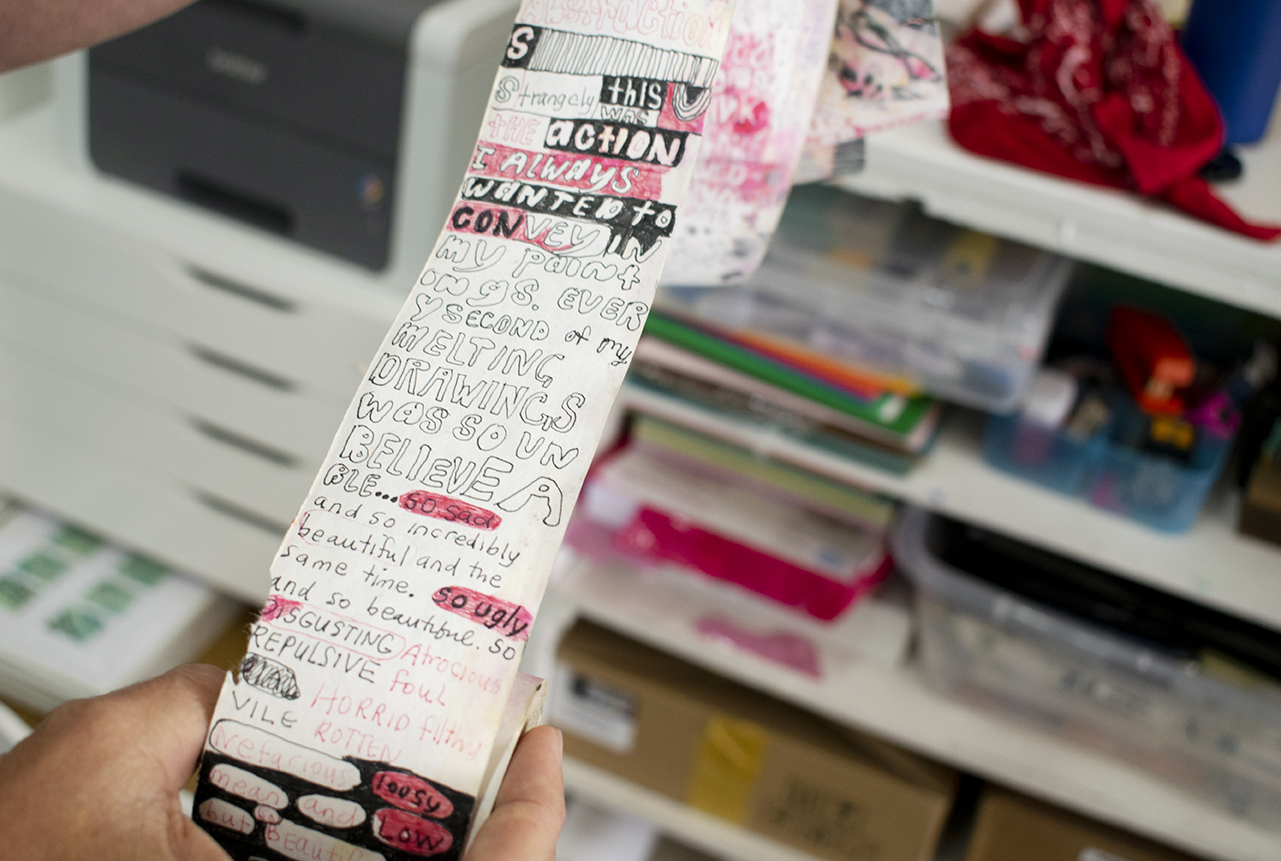

For many years, I walked into my studio and had no idea what would come of my day. Paint covered every surface. I had little furniture and little structure in my work, or life, in general. I left every single moment to spontaneity. It was as much a burden as it was a freedom. I practiced this way for over a decade. During those years, I was really searching and I allowed myself this level of freedom in the hopes that I would eventually find something. Ironically, I was very disciplined about this lack of structure. I wanted to give myself every open door that I could in the process of making.

Though I have a side of me that is very free, I have another side that is very rigorous and determined. Once I felt that I had my footing in the studio in terms of technique, material, form and color, I was able to implement much more structure into my practice. My work began formulating in a way that called for more organization, and so it was the work itself calling for a more regimented approach in the studio. Now I synthesize the two sides of me; there's still spontaneity and freedom in the process–I'm constantly reworking–but at the same time, I stay on track and on this planet. Whereas, I used to rework pieces into another galaxy.

Fish and bees are recurring motifs in your work, so would you care to elaborate on their relevance?

The bees are a reflection of what I felt was happening in our culture around the time Trump was running for president. It felt like we were entering a dangerous time, like what one might feel walking into a swarm of bees: the sense of chaos, the hundreds of them flying around, the not knowing which one might sting.

The fish are from a series of female hunters I was making. Fish is a symbol loaded with complex and multivalent meaning because it's used in so many different religions and cultures. Together, the weighted history of the fish as a symbol and the image of the woman hunter felt like a powerful and challenging combination to work with. The female figures bring the fish, and all its attendant meaning, up from below the surface. They're exposing and expressing what has been kept out of sight and underwater until now.

This might be sound frivolous, but do you have issues with people touching your work? It's so tactile and textural, I'm sure there's a temptation…

Yes, people are prone to touching my work. I had a show at the Henry back in 2017, and the museum called me halfway through the exhibition. They said that even though they had a security guard watching over the works, people would still try to touch the paintings. They wanted me to send a sample of my paintings so they could give viewers a chance to interact with the texture. I think it's amazing that people are drawn to my work in that way, and I want them to feel a physical connection to the pieces.

Narrative is at the helm of your paintings, dipping into scenes and structures of your own creation. When formulating a series, do you have a specific story in mind that unfolds onto works, or is the work drawn from history?

I often begin a new series of paintings, not with a story but with a general theme—the female hunters, for example—then I search for points of connection throughout history. I find my way by building connections, which can form a sort of loose narrative structure. I trust the historical references and my intuition about what figures and scenes can communicate that complex lineage of inspiration.

Can we talk about the subverted gender roles in your work? A lot of female figures are hunting and bringing home the kill. Why is it important to flip viewer expectation?

One day a few years ago, I was sifting through a thrift store in Georgia and found, buried underneath a stack of books, a painting that has stayed with me to this day. It was a painting of a large ship at sea, with roaring waves crashing against the side. The ship was steered through the storm by African American men, with their hands painted in heavy brown strokes and their paddles cutting through the white caps of the sea, all done in thick impasto layers. Inscribed with a line, which looked like it was carved with a paperclip, were the words 'WE RUN THINGS'.

The encounter with this painting was one of the most powerful art experiences of my life. I had found a work of resistance, a work of quiet power. I thought about that painting many times over the years and wanted to honor it. I began to explore in my own work, taking the language of Egyptian pictography and using it as a lens to explore female empowerment. While looking at Egyptian renderings of men pouring water, cutting fish, and pulling carts—basically doing the heavy lifting of daily life and “running” things”—I thought of the African American men in that painting in Georgia. WE RUN THINGS. I started making works where women did the heavy lifting and were running things. I felt empowered to reimagine our historical images and tell a different story.

What do you have coming up as you look towards 2020? Where can we see more of your work?

In 2020 I have a solo exhibition at the Kemper Museum and a solo exhibition at Zidoun Bossuyt in Luxembourg.