Around 1957, French artist François Dufrêne, long associated with Lettrist and Ultra-Lettrist poetry, started removing posters off the streets of Paris and began to present them framed and hung as paintings. He called his repurposing “almost geological infrastructures,” constructed, on the street, by the different layers of paper. They were time-capsules of a living organism that was the city, a conversation in public spaces that was layered by time, by cultural evolution, by place. You can tell a lot from a city by looking at what we, as citizens and residents, leave behind as opposed to what we see above us in billboards, paid advertising, contemporary architecture, you name it. I didn't know much else about Dufrêne's sound practice, but in actuality, these re-contextualized poster works were full of sound; a sound that we make as a culture when we interact with the place we live.

One of the great things about the Nuart Festival, and now celebrating its 8th year in Aberdeen, Scotland, is that it is an actual living, breathing, organized idea of the use of public space. And as he so often does, Nuart's founder and curator, Martyn Reed, sets a yearly theme, wheras this year it was a look at "Living heritage." He wrote of this idea that "living heritage is the dynamic side of cultural heritage: heritage which is continuously transformed, interpreted, shaped and transmitted from generation to generation. It also represents the participatory, co-creative dimension of cultural heritage, and is characterised by its transient, non-stationary and hard-to-grasp qualities."

A relevant discussion point as it pertains to street art festivals, and Nuart is perhaps the best in the world at this, is bringing together an international roster of artists and transforming a particular place into a new space. Each artist brings their own heritage to a wall, a wheatpaste, a tag, and in return, the city obliges and reciprocates with its own history. This is what makes working in public space so powerful: there is a give and take, and a sharing, that occurs. What the 2024 edition of Nuart Aberdeen attempted and successfully contemplated was a sense of a shared past and where that history is best documented and preserved. And it also highlights how much of cultural heritage should be malleable and should be flexible with the times. We live in times of transition, of war, of immigration, of movement, that sometimes the simple act of creating art in public can illuminate the beauty and evolution of shared history.

The ephemeral nature of street art versus the archival nature of the museum's role was a central discussion this year as well, and what I love about Nuart is that both are completely with their own merit and both serve a role in our society. We need the intangibility of street art and the preservation of the museum. They work together in harmony. And we shouldn't be afraid to ask of our museum's to be privy to our public discussions of how much our cultural heritage is evolving, just as the streets should be welcome to the discourse a museum offers in the likeness of putting our culture into an archival context.

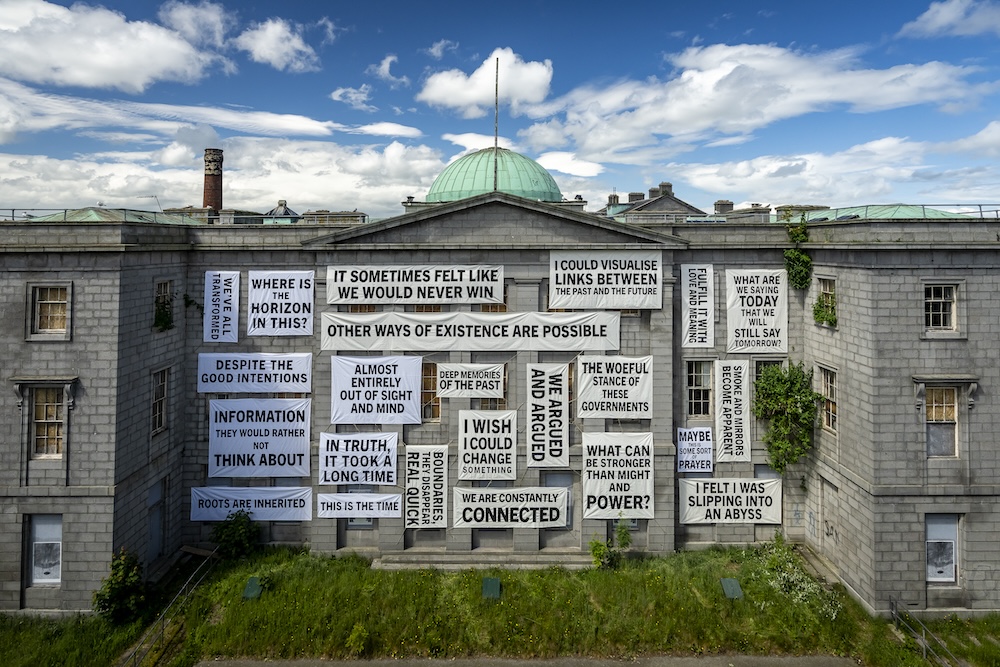

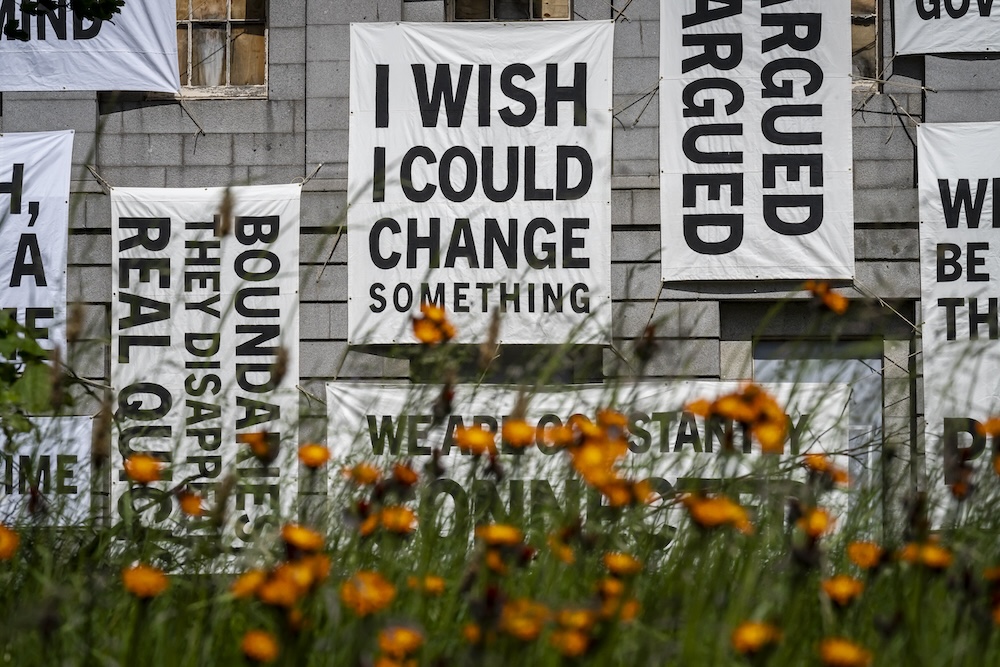

There was something quite striking about this idea in this year's line-up, with Tel Aviv-based Addam Yekutieli's collaboration piece with local Aberdonians in a project that Addam asked for those to "share their experiences of disillusionment and hope, and painted them onto huge banners." Those banners, placed as an installation on an abandoned hospital in the center of town, speaks not only to the war in Gaza, but also a powerful message that speaks to a local conversation. The push and pull in these poetic verses felt both personal and international. Cairo's Bahia Shehab's mural in the center of the city was a a "graphic interpretation of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s poem 'You Are Forgotten As If You Never Existed,;" directly translating to “Bear witness that I am free and alive.” CBloxx's brilliant mural brought forth imagery of the Picts, a vanished nation, chronicled by Vikings and Romans but not by themselves, as the artist notes. "The Picts communicate their own existence to us only through their carved stones which are intensely scattered across Aberdeenshire and the east. The last pagans in Scotland before religious conversion, displacement, and cultural erasure."

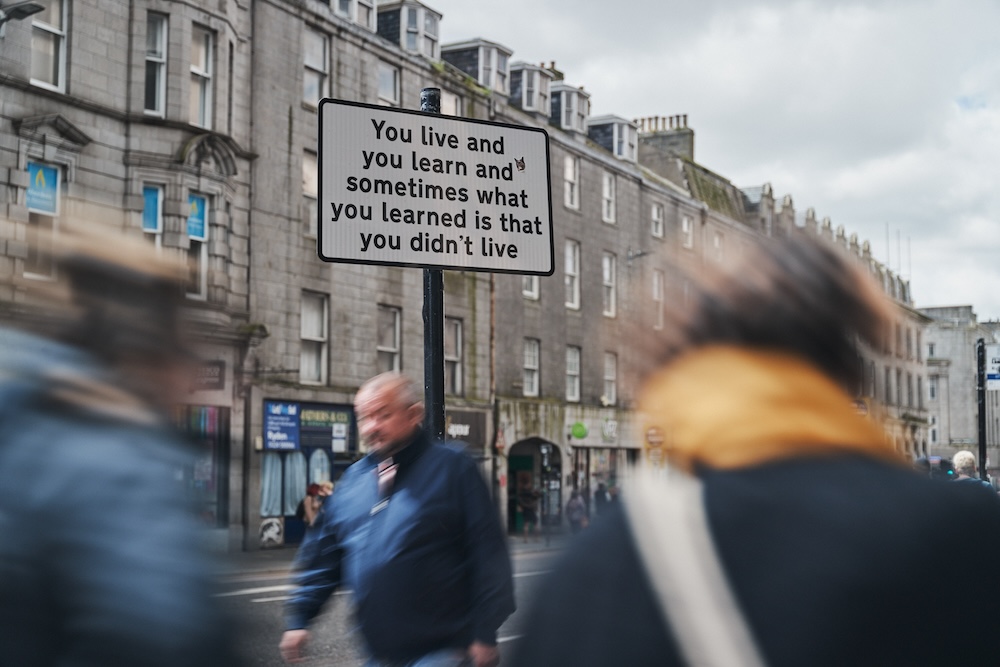

There was also plenty of play this year. SHOE's gigantic text mural read "Real graffiti writers do this illegally hanging from a rope in the dark." Molly Hankinson, in perhaps the best demonstration of the ephemeral nature of the street art form, painted chalk with local youth, only to have the rain wash it away hours later. Fitting, and quite poetic. Wasted Rita's interventions were the kind that made you stop in your tracks, therapeutic and truth-telling devices disguised as civic instructions. Case Maclaim, KMG, Mahn Kloix and Millo all gravitated to storytelling in their works as well, using bits of Scottish history and personal tales to best bring their own heritage to the granite city.

Of course Hera, one of the pillars of the street art pantheon, returned once again to Aberdeen after her beloved mural painted in 2017 was destroyed as part of a city infrastructure change for a massive mural that felt like a homecoming. The work references Scotland's national animal, the unicorn, with text that reads "I am the keeper of magic… but I’m happy to share."

So Dufrêne. Why did I start here? Because it's about how we feel and hear a city, how available we are for that city to change, how vulnerable and strong we have to be to have the city and it's heritage both mirrored back to us, researched deeply, but also given new ideas as to how they can open their doors to new stories to emerge. Cities are alive, and they do speak. We have for so long tried to understand what public spaces are made for, how they should function, and what they say about our heritage. What monuments do we cherish, do we keep, do we build? Nuart, through the lens of street art, is just trying to get us to look at the places we live, understand how they function, and how we can learn from others how to best exist in them. —Evan Pricco

All photography by Brian Tallman, Conor Gault, Gwyndolin Temple and Clarke Joss