From the late 1960s to the early 1980s, renowned Japanese war photographer Akihiko Okamura created a remarkable, compelling and largely unseen body of work in Ireland, north and south.

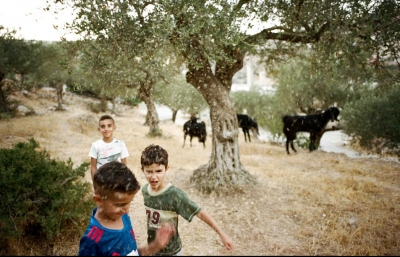

After covering the Vietnam War, Akihiko Okamura went to Ireland in 1968 to visit the country of JFK’s ancestors. Soon after, in 1969, he decided to move to Ireland with his family. From then on, he continually photographed the Troubles in the North and his life with his family in the South, until he suddenly passed away, in 1985. His photographs of Ireland, which have barely been seen before, demonstrate a unique artistic vision. This uniqueness is partly because Okamura chose to live in Ireland: of all the international photographers active during those years, he was in this sense a singular case of absolute commitment to Irish and Northern Irish history. This fusion with his subject matter led him to create images which were innovative both in terms of his own practice and of the photographic representation of the Troubles. His profound, personal relationship with Ireland allowed him to develop a new method of documenting conflict: poetic and ethereal moments of peace in a time of war.

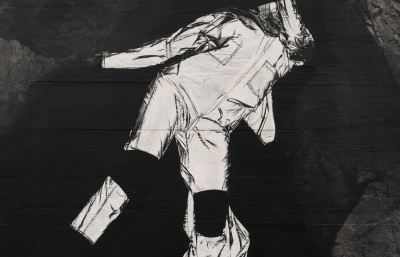

Unlike other representations of the North of Ireland at that time, Okamura’s photographs are almost all in color. Made in the North as well as in the South of Ireland, his photographs broke from the photojournalistic tradition, creating a series of still lives and abstractions. Their gentle, muted palette operates in counterpoint to the violent situation in which they were produced; they are remarkably out of sync with the conventional, black-and-white, “heroic” photographic representations that have come to define this period. Okamura’s work reveals a more subjective perspective, often going beyond conventional photographic representations of riots, burning cars and bombed buildings, to capture quieter, intimate, quasi-surreal moments that reveal his empathetic concern for the communities he photographed. This intuitive narrative choice was intimately connected to the depth of his attachment to Ireland and the Irish people. While Okamura remains highly respected in Japan, his Irish work and experience, crucial to both his oeuvre and his personal life, had never been studied until now. The rediscovery of this archive constitutes a revelation both for the history of Japanese photography and Irish history.

The Memories of Others is on view at Photo Museum Ireland. A book of the same name is published by Prestel.