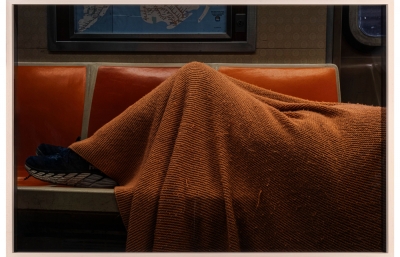

A few months ago I wandered through a flea market in Mexico City with Tania Franco Klein while she searched for props that might exist in the world of her photographs. Among the morning's spoils were a few questionable (aren’t they all?) old dolls, a large piece of glass whose original function remains a mystery, an unreasonably large chess set, and an equally tiny deck of classic Lotería gambling cards. Klein is always hunting, chasing a feeling or emotion that she aims to capture in her work. Some paths loop back on themselves; false peaks, detours, and enticing distractions are all part of the process, but it's often the apparent dead ends where the breakthroughs occur. In her latest work, Break in Case of Emergency, now on view at Rose Gallery in LA, it’s a catharsis that she’s been after. For her characters, who have always been stuck, searching, or on the run, it's empowering territory. "I finally found ways for them to really own their space," she explains. "I was so obsessed with particular things happening in the scenes, and it just wasn't working. When I finally gave up on that, I started being playful... and when it finally became playful, it was actually joyful.”

Alex Nicholson: You spent a lot of time imagining the installation for your new exhibition. Were you thinking about that as you were shooting, how the images were going to look on the walls?

Tania Franco Klein: I think this is my best show so far installation-wise. It’s always been such a big part of my work, not just the making of the pieces but how they will look in the gallery. It’s been exciting to realize it. I’ve started working a lot with party elements and backdrops, there's something celebratory in the work in a strange, bizarre way.

Did you expect that when you started this new series?

No, it took me so long to figure it out but that's what always happens. I have a small sense of it, like, a phrase, a title, a feeling, or an emotion that I want to create. But during that process, a lot of things happen and sometimes I go very far in a direction that doesn’t work and I just have to redo and redo and redo.

When we last talked for the magazine you were just hinting about where you thought your new work might be heading. You told me that after the heaviness and intensity of the past several years, you had this thirst for "very explosive things." It’s been interesting hearing how those feelings have evolved into this new body of work.

Even though I think all of my work coexists in the same universe, the physicality and way that my characters exist in this new series are so different from my previous work. It took me so long to detach from my understanding of who my characters were and to find their new language.

How did your characters experience this transformation?

My characters were always very contained. There was always something simmering but they weren’t doing anything about it. They were really stuck in their situations. They were victims of their own thinking, stuck in that psychological process. In Proceed to the Route, they started being a bit more active, trying to run away from themselves and find new paths but for this one, I finally found ways for them to really own their space, to own these scenes I've created for them.

You seem to have settled on the word "catharsis" to explain this.

Yes, when I first started this work I was very interested in the idea of catharsis, but mostly in the way that the spectator experiences catharsis through other characters in cinema, television, and entertainment. I feel like there can be a lot of pleasure in that experience of watching other people do things we might not do in our own lives. Obviously, I'm not talking about violence or killing people, but small little rebellious acts. You get to live that rebellion through someone else. If you see someone breaking things or screaming, there might be some sort of release in that process.

What were those early directions you went in that didn't work?

I did very crazy things. I went to those break and smash rooms and I was doing all this crazy research about experimental therapies and photographing all these extreme moments, but they all felt overly dramatic. They weren't playful. I wanted there to be some enjoyment in the catharsis. So later, instead of concentrating on what was happening in the scene, I decided to concentrate on the emotion itself, which was like this sense of empowerment and knowing that the person in front of you is experiencing this situation where they're doing things their own way. There's this compelling element in the way that we empathize with the characters. We're so well-behaved nowadays. There's something very cathartic about small rebellious acts. I didn't want my characters to suffer because I feel like they were finally so empowered about experiencing life on their own terms and finding their own ways of doing things. I was concentrating too much on the actions themselves that I forgot about what was most important for me, which is always the emotion that you get from that action.

How did you arrive at that point? When did that realization happen?

It’s always connected to the process. I was so obsessed with these particular things happening in the scenes and it just wasn't working. When I finally gave up on that, I started being playful and noticed the importance of subtler things. And when it finally became playful it was actually joyful. Before that point, I was always exhausted. If I’m coming home after a day of working and I’m completely exhausted, that usually means there is something wrong with the work because it should be very invigorating, you know?

We were talking about the film Daisies earlier. That was a big influence on you?

Yes, it's from the '60s and it's about these two girls that get tired of the materialistic, bourgeois society they live in and spend the whole film breaking the way things are done in a very enjoyable, child-like way. They find power in doing things differently than they are supposed to, by experiencing situations their own way. That was very inspiring to me.

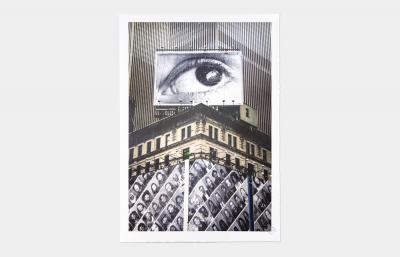

Tell me about this other project that’s on display in the gallery, the subject series.

I always try to combine two projects in a show because I feel like there are different elements of my work that coexist together. It’s an anthropological exercise about the way we profile people and the way that we see “the other.” I noticed that because my photographs are so cinematic, people often read the character based on the scene. So what I’ve done is take a scene and recreate it with a lot of different subjects. The same photograph with a different character in it. How would we read that, then? How would we change the way that we read it based on our different cultural and personal backgrounds?

Logistically how did you manage the project? How many people were you photographing?

106 people, 10 minutes per person, and one after the other. It was so much different from the way that I normally work. It's not so experimental, where I'm changing the scene and moving around. It was super invigorating for me to suddenly go from being alone 24-7 to shooting 106 people. It was so interesting. Nobody knew what they were doing there, haha. I explained a little bit but I feel like unless you see the whole project, it’s hard to understand.

How many of these scenes are you going to do?

There are going to be 10 chapters because I feel like if you see it all together it’s too much information. It’s better to see one chapter and then release another at a different time.

You've told me each project is a process of working through something for yourself. With this exhibition do you feel like you’ve worked through this idea? Is it done?

No, the project is not done. None of my shows have ever been with a finished project. It's just a place in the project. It took me so long to get the language of the work to understand it that there's still energy in me to discover new ways of getting to that place. I feel like when I stop doing a body of work is when I feel like I can redo it over and over and over and over with my eyes closed because the language is so much a part of my brain. That's when it gets boring. There isn’t that excitement of having no fucking clue how I’m going to get to the next point.

How much of that is the surprise of not knowing what you’re going to get and the excitement of seeing the result?

That’s exactly it. When I lose the surprise element or I feel like things are becoming too redundant, that’s when the project has reached its limit.

Does exhibiting the work before you feel it's finished help you finish? Just seeing it on the wall and experiencing it physically and watching other people experience it?

Definitely, yeah. There's nothing like physically experiencing how everything comes together. When that happens, I realize which areas of the work I can explore more, especially with the complicated installations I’ve been building. I would like to do more pieces like that or think more in that way. But that's only after I actually finished doing it in the show, that I realize that.

That's such an interesting idea because I would imagine many people might think that an exhibition or book is often a finished project.

I never see it as a finishing point. It's kind of like a starting point for something to grow in a separate direction that might complement the work in a different way.

Tania Franco Klein’s Break in Case of Emergency (Flies, Forks, and Fires) is on view at Rose Gallery in Los Angeles through April 15th, 2023, and will reopen May 13th through June 3rd. View chapter one of her Subject Series here.

Flea market photos by Alex Nicholson