The exhibition titles Chant d’Amour in 2022 and Mort Heureuse in 2025 chosen by Xie Lei, evidently bring to mind Jean Genet and Albert Camus, yet these discreet tributes emancipate themselves those tutelary figures, acting in a more general manner simply as a starting point for two series of paintings.3 The omission of the articles “un” and “la” is certainly of importance: Is it not the means Xie Lei wishes to use in order to lead us down the pathway of song(s) and death(s) that remain radically undefined?

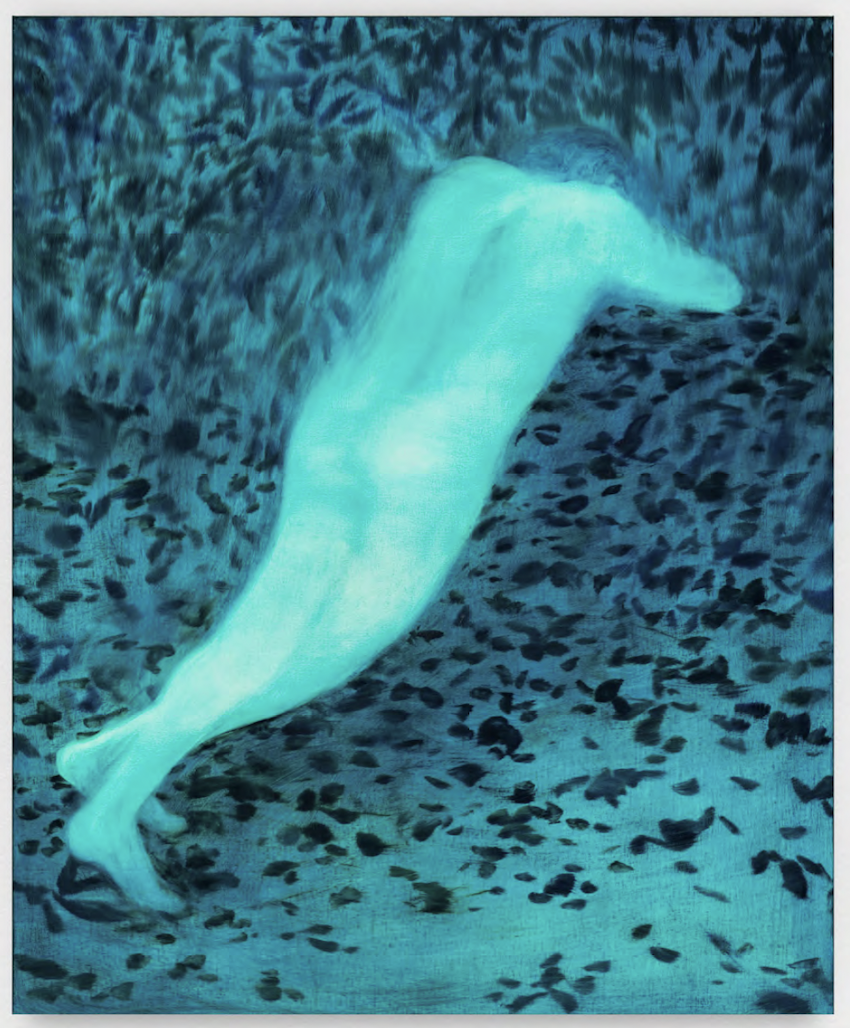

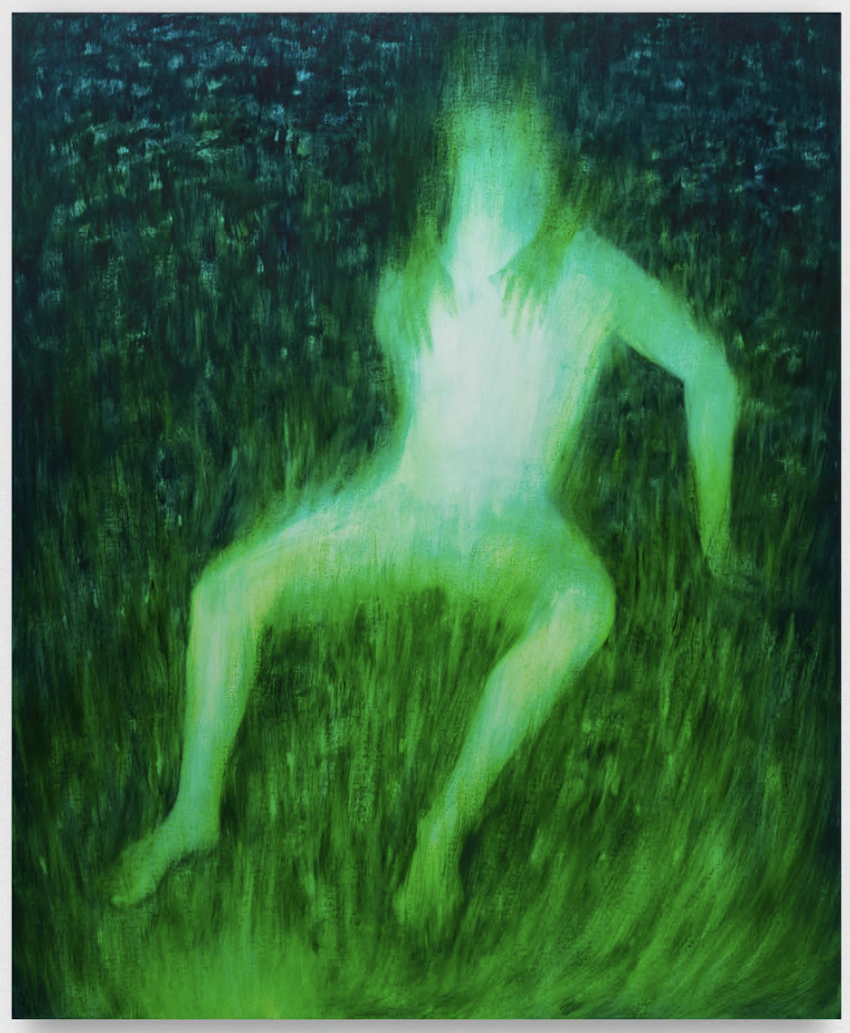

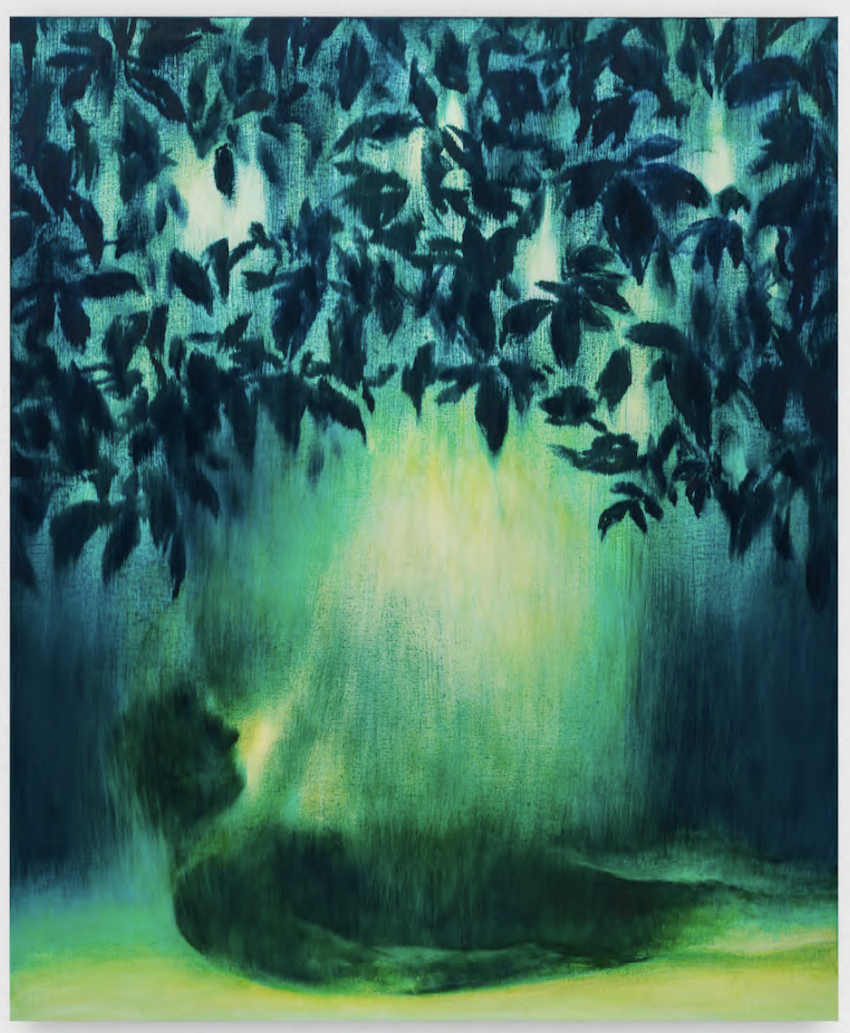

This lack of definition or ambiguity, immediately noticeable from the titles at the threshold of the exhibition, is a significant feature of Xie Lei’s painting. It is something I already mentioned in a previous text concerning his practice:4 the features of his figures preclude them from any form of categorization, be it gender, race or class. In an era that is justifiably concerned with positionality5 and involvement, Xie Lei depicts bodies subjected to a kind of identity fugitivity. Indeed, his pictorial language includes, amongst other techniques, flat tints in oil, which are successively scratched and scraped—using brushes, paper and even the artists hand, the fingerprints of which can occasionally be discerned6—until the contours of the bodies are blurred into mysterious colored halos. It seems to me, that in his painting, Xie Lei is striving for what José Esteban Muñoz termed as the psycho-sociological concept of disidentification,7 i.e. an aesthetic and political strategy aimed at avoiding any form of identity assignment.

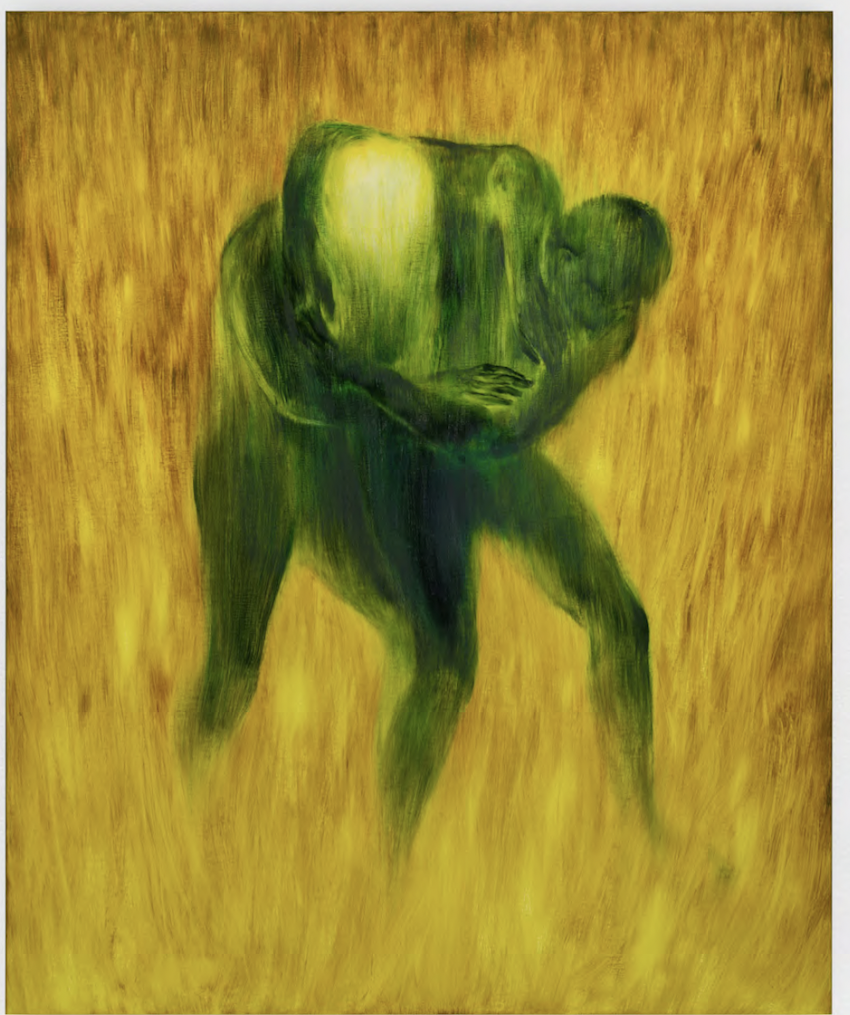

The theoretical references cited by Xie Lei are however quite different and more familiar: Sigmund Freud and Julia Kristeva,8 and thus linked to the field of psychoanalysis. Moreover, Xie Lei has long used the term oneirique or dreamlike to define his practice. I want to highlight this particularity since art shares with psychoanalysis a focus on exploring the question of our representations.9 In contrast with repression which bespeaks the refusal to represent a desire seen as problematic, I’m more interested in the dynamic mechanisms of the unconscious, such as dreams and drives (including the death drive, whether happy or not, which brings us back to the title of this exhibition) and which both have something to do with desire. Xie Lei’s characters are all, sometimes indistinctly, “fighting, making love, dying or being saved.”10 My argument here is that the impossibility of precisely characterizing the scenes the artist shows us, reflects the representation of the impossibility of linguistic intermediation (which is in fact, the very definition of the unconscious). To put it another way, what Xie Lei depicts on canvas we can only imagine and is beyond words, things that might uninhibitedly erupt into our consciousness. The scenes he has been painting ceaselessly since at least 2020, are part of an ongoing cycle, whose very subject is illegibility. The above-mentioned disidentification would be met with indescribable acts, in the linguistic rather than the moral sense.

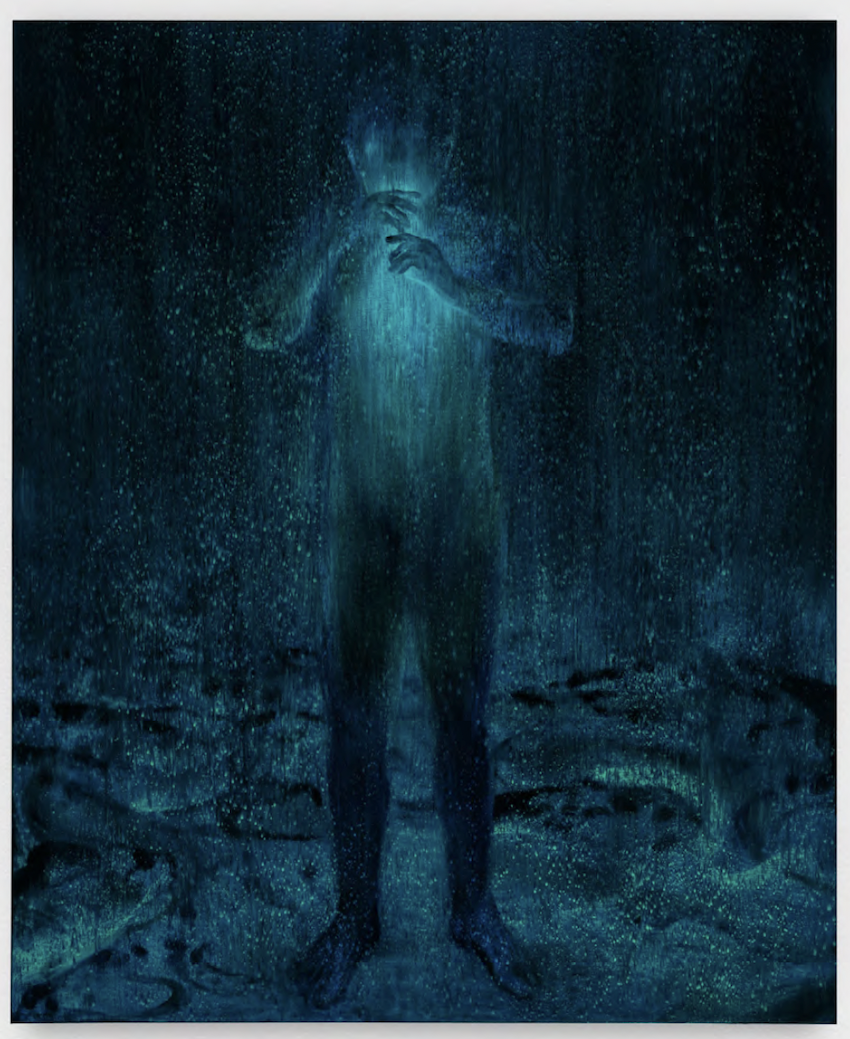

Within this long series I’ve just mentioned, we should note that the bodies—and whatever they are doing—have been increasingly dissolving into the colored backgrounds, like the barely discernable face behind two dark hands into the blues of Intimation (2024).11 The treatment that this ghostly presence has undergone—is it even possible to speak of a body here?—is the same as that of the background: powerful, vertical brushwork, very different from the circular touches used for the hands. Although the hands might appear black, Xie Lei never uses either black or white to compose the infinite complexity of his hues.

Finally, to emphasize the tension and duality that emerge from his paintings, Xie Lei likes to identify his works with the stylistic device of the oxymoron—“Mort Heureuse / Happy Death” is just one example. “How can one represent ambiguity in painting?”12 asks the artist, who himself discerns oxymorons both in his work and in his own life. “As a painter, you’re confronted with white13 and death every day. How is it possible to make something invisible appear?” —Victorine Grataloup