The smallest fragment of source material related to natural history can evoke sweeping cinematic images.—Walton Ford

Gagosian is pleased to announce an exhibition of new paintings by Walton Ford, on view through April 23, 2022 and is his first exhibition with the gallery in New York.

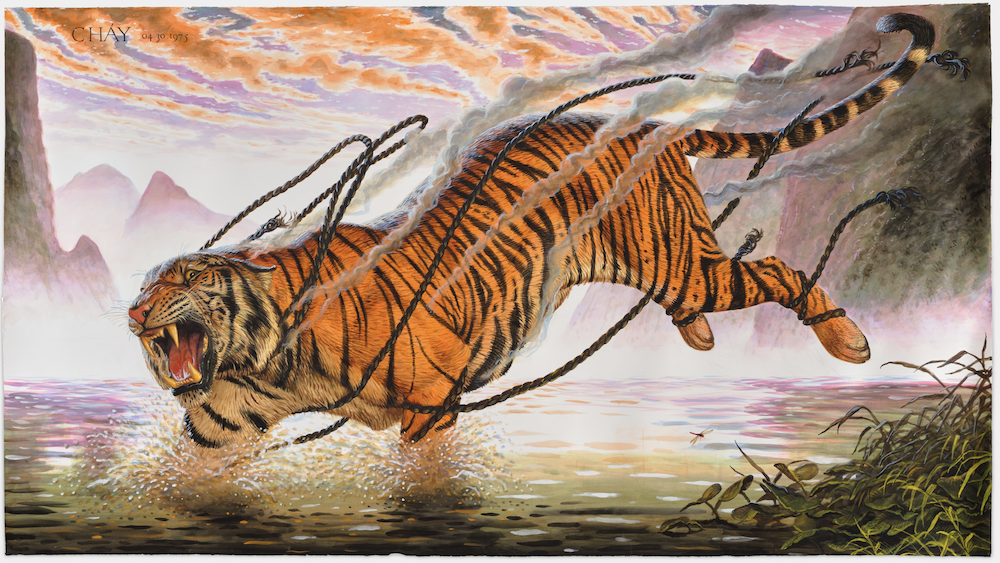

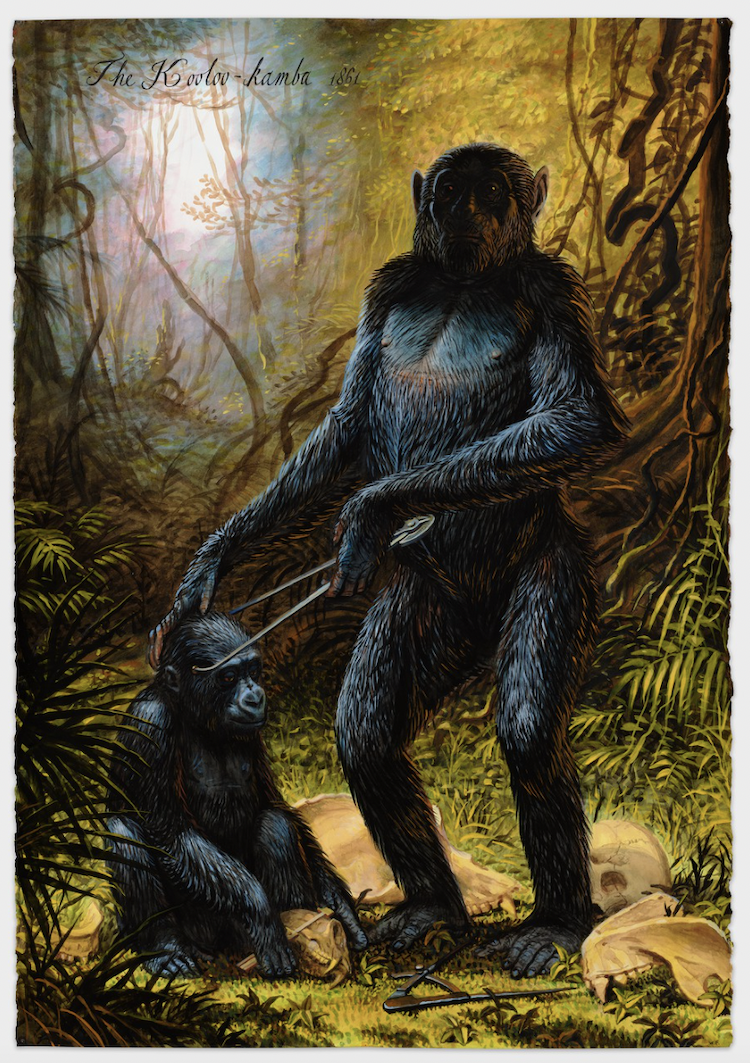

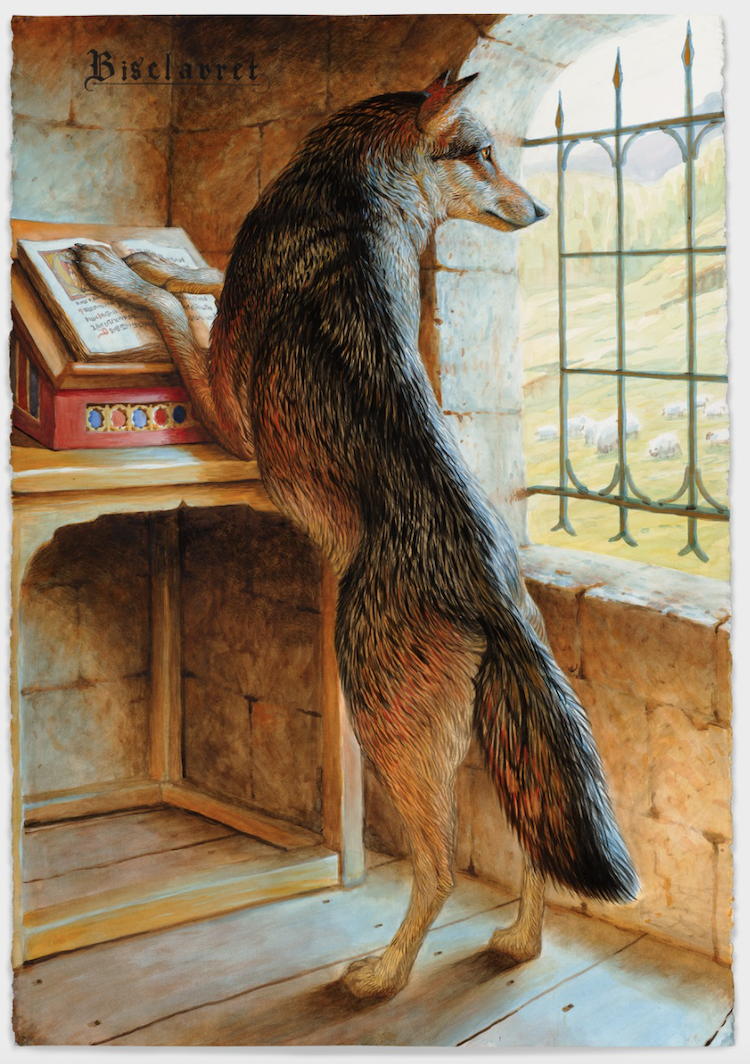

Absorbing the techniques prevalent in scientific field studies, explorers’ notebooks, and lushly illustrated natural history books, Ford’s watercolors recast, reverse, and rearrange the conventions of wildlife art. His practice is research-driven, responding to such diverse inspirations as Hollywood horror movies, Indian fables, medieval bestiaries, colonial hunting narratives, and obscure zookeepers’ manuals. Ford’s visions are consistently of wild rather than domestic animals. His monumental paintings seek to show us what it means for such animals to live not so much in nature as in the human imagination.

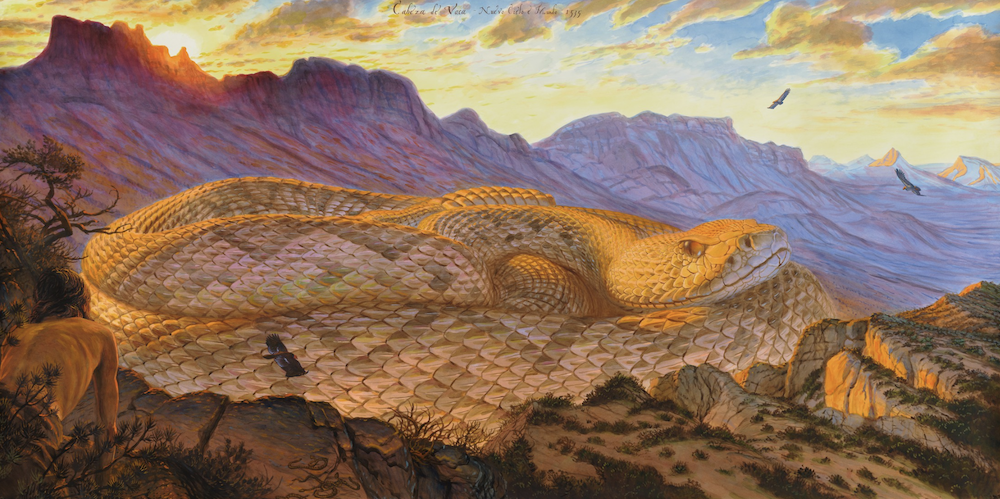

Cabeza de Vaca (2021) takes its name from the sixteenth-century Spanish explorer. Shipwrecked on the Gulf Coast in 1528, he journeyed lost across the American Southwest before finally reaching Mexico City eight years later. The painting is an exploration of human fear and paranoia when faced with the unknown, the mountainous rattlesnake a dream symbol suggesting the misapprehension and trauma of first contact.

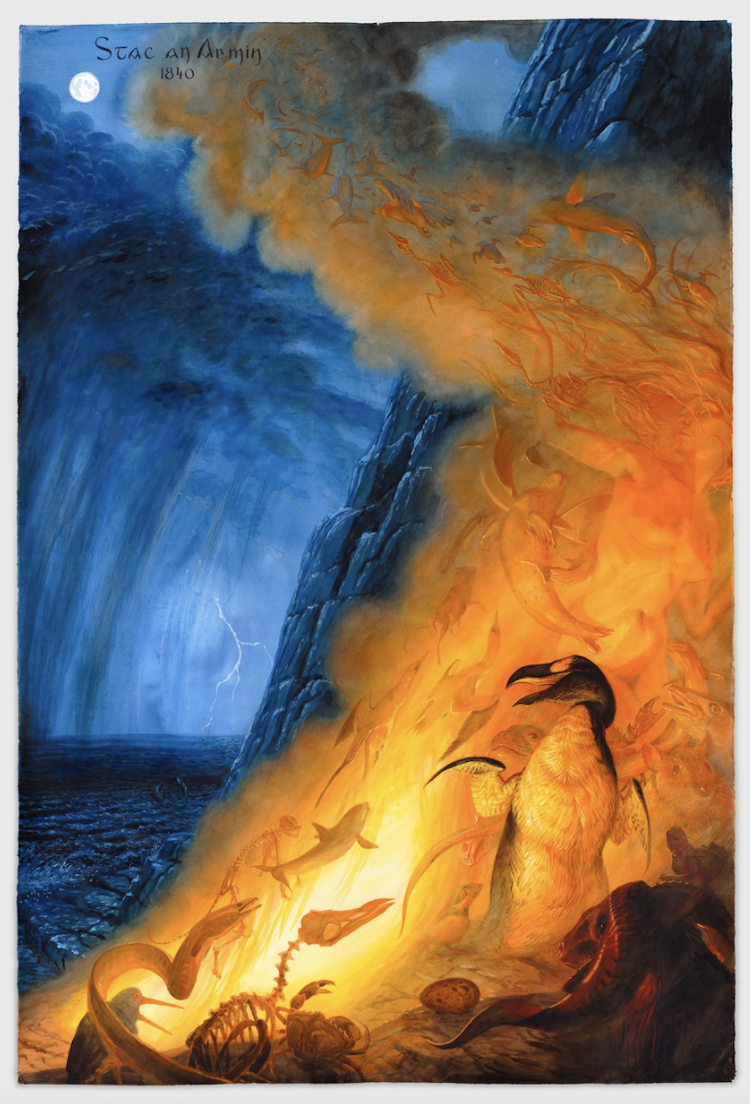

Another phantasmagoric work, Stac an Armin (2021) examines one of the last recorded sightings of the great auk. The bird’s unique appearance caused the fishermen who captured it off the coast of Scotland in 1840 to believe it was a witch. Here, Ford transforms the local fauna into the ghouls and spirits of a witches’ sabbath, depicting the homegrown monomania that led to the men capturing and killing this now extinct bird.

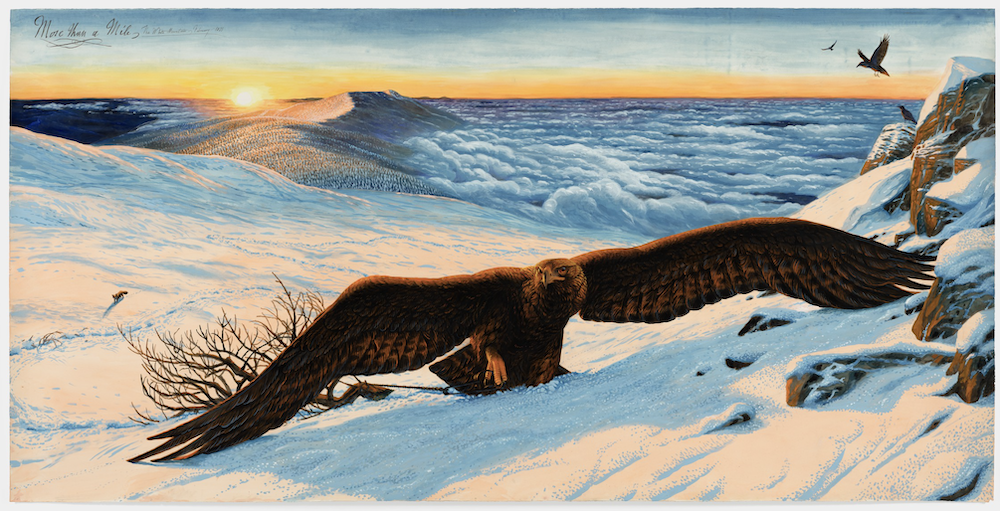

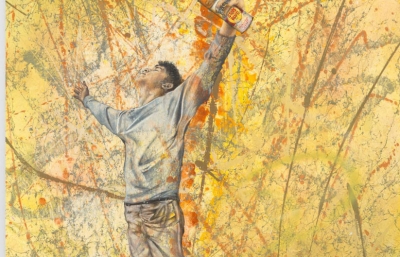

In More than a Mile (2020), Ford diverges from fantasy images to create a kind of visual reportage of an incident from 1833. The golden eagle depicted was caught by a farmer in a fox trap, which it dragged for more than a mile through New Hampshire’s White Mountains. John James Audubon purchased the bird, killed it, and painted it. By taking the point of view of the eagle, Ford brings the viewer face-to-face with the bird’s ordeal.