Perrotin Tokyo is pleased to present Bath, a solo exhibition of paintings and works on paper by London-based artist Sara Anstis (b. 1991 Stockholm). This is her first presentation with the gallery.

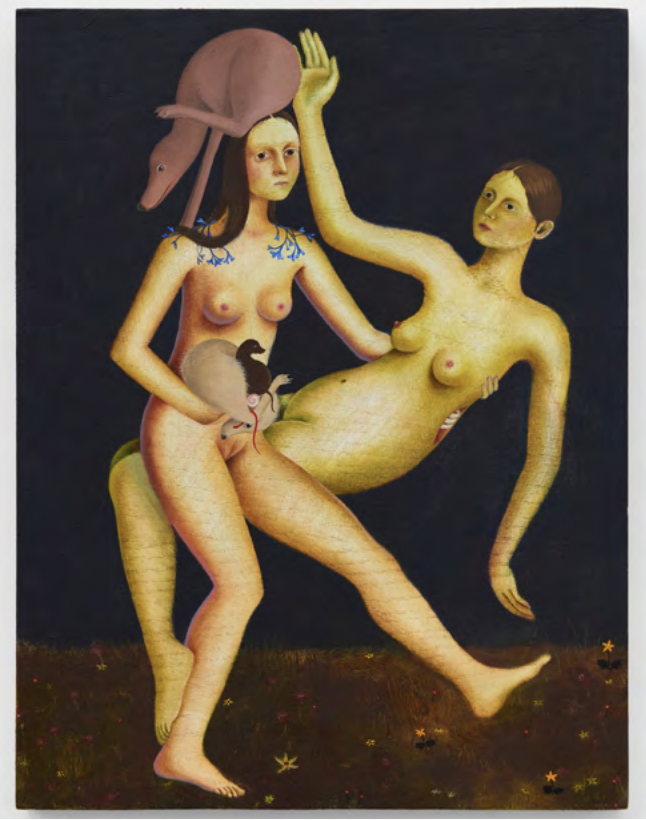

Sara Anstis’ otherworldly scenes—where figures, often nude, commune amongst themselves and in the company of animals— present a dreamlike logic that can be partially decoded through a contextual viewing of art history. Precedents to Anstis’ imaginative worlds include those within the Surrealist movement, but her own interests stretch much further back and incorporate a wide swath of visual and thematic sources. Figurative fragments redolent of the medieval and early renaissance merge with symbolist elements and tones that recall color theory and geometric abstractions from the mid-20th century.

A significant part of Anstis’ artistic output consists of works on paper where she has developed a pronounced sense of materiality—thanks to both the texture of her chosen surface, toothy watercolor paper, and to the hazy layer of pliable pastels she lays on top. The results of this considered layering are saturated two-dimensional images that appear to vibrate off the page. This exhibition marks the first time that Anstis presents paintings on wood panels, in which materiality once again takes a central role, this time projecting the panel’s woodgrain through the layer of pigment and creating a composited effect that merges substrate and paint in equal measure.

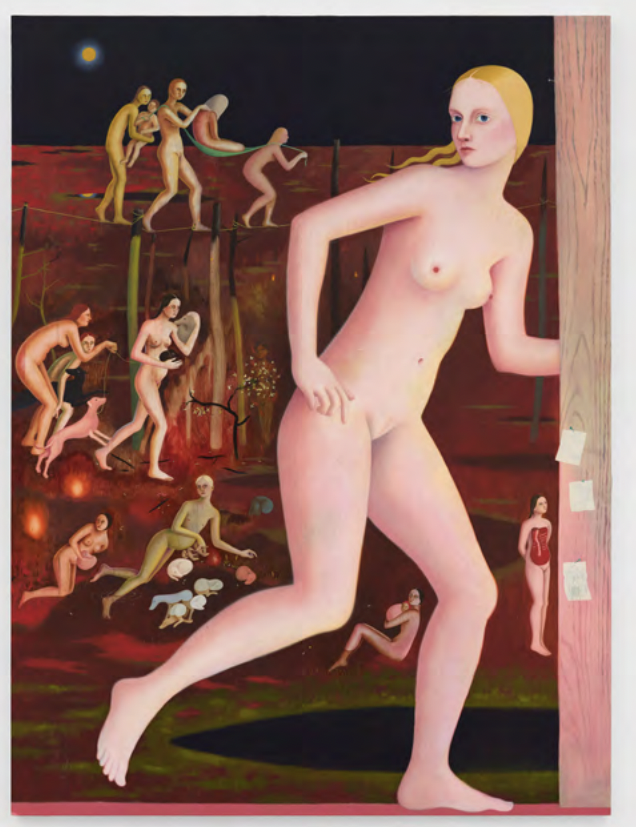

In Running, Red, a nude woman passes through the frame with her gaze firmly fixed towards the viewer. Behind her, in a hellscape where fires burn in the distance, are several more figures in various states of undress moving in the same direction. Calling to mind Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Dulle Griet (a monumental painting whose environs owe a large debt towards Hieronymus Bosch, where the central female warrior figure Dull Griet leads a mob of women to pillage Hell), Anstis’ employment of the character’s fixed gaze feels decidedly contemporary—a device that appears to break the fourth wall of her conjured scene, allowing it to freeze time. In a divine flash we are caught in a moment, and instead of being a mere bystander to the events, we’re forced to engage with the scene before us. The line between nudity and nakedness is never clear and Anstis asks us to look closer to find our own answers.

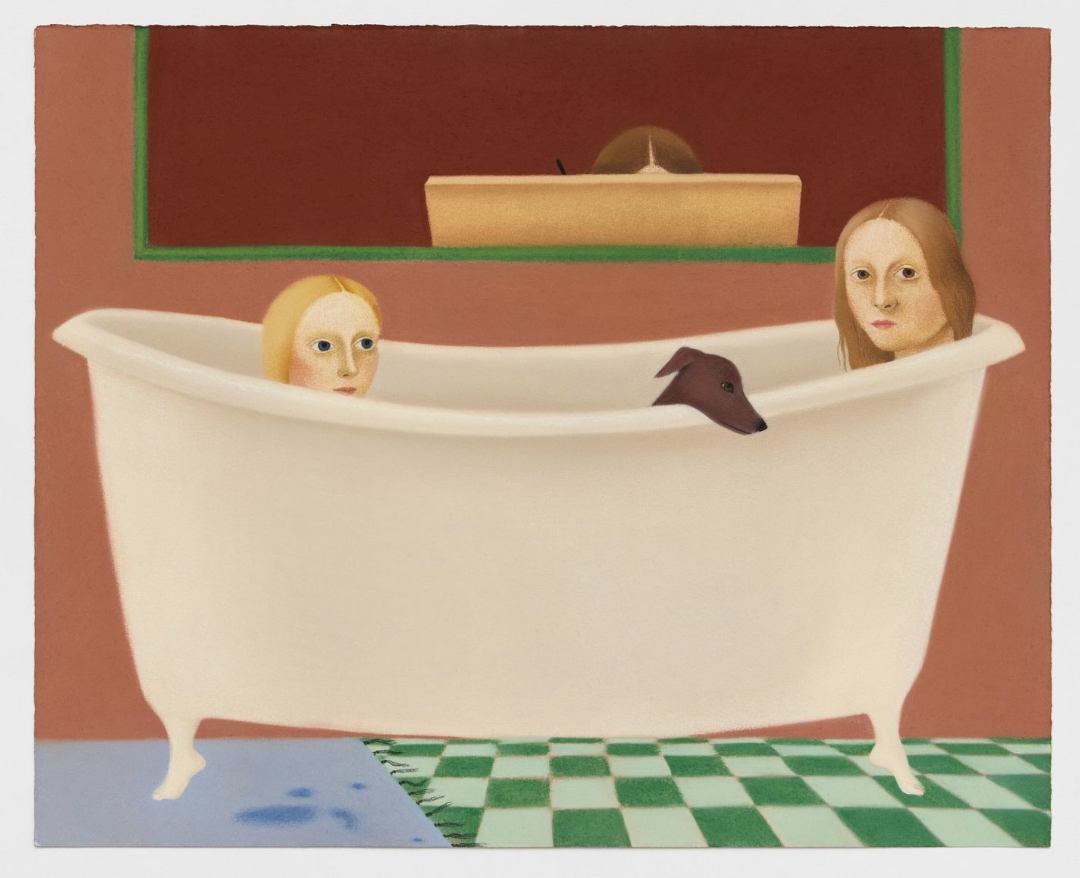

Many of Anstis’ scenes appear to present cryptic parables, where the relationship and values between the figures, their environments, and ourselves is one we try to work out as we peer upon them. A dour clothed figure dominates the foreground of Dinner Table, standing next to an empty plate on a table. Behind is a nude woman, one arm outstretched. The narrative isn’t crystalline but suggestive and questions abound. Throughout the exhibition, a theme of constant revealing and concealing becomes clear. In Laundry, Anstis places a layered line of differently colored fabrics before a figure whose elongated neck suggests a degree of undress. The fabrics work as a device to conceal her body, and again ask us to consider the scene’s tale. Similarly, the bathtub in Bath conceals the bodies of its three inhabitants, who gaze towards us contentedly from within its protective confines. The painter is a presence reflected in the mirror above the bathtub whose eyes are concealed by a drawing desk but whose gaze is available through her rendering of the entire scene.

The show’s title, Bath, recalls many images from a long line within art history, but it was the idea of a bath in the Roman sense that allowed Anstis to connect the quotidian bathtub to her visions of a sulfuric underworld. This thread—that pulls us from the domestic to the infernal and back again—is tangible throughout the exhibition, and evidence of an artist whose vision is all-encompassing, absorbing, and beguiling. —James Casey