A more sinister, looming presence takes hold in Samantha Joy Groff’s latest painting series at Nicodim Gallery, as she considers ritual practices, exorcisms, and religious texts, including the Book of Revelation. The apocalyptic text—primarily found in the Christian Bible, from which the title of the show, Prophecy of the End, is derived—sets a foreboding scene.

The end of the world, as the prophetic script details, encompasses a tremendous amount of human suffering in the ultimate battle between good and evil. Conquest, war, hunger, and death result in the collapse of society as we know it, while Christ returns with an army of angels to restore the just and to destroy all evil in order to usher in a new kind of creation.

Action-packed renderings of the subject have long captured imaginations—including those of such masters as El Greco, William Blake, and Peter Paul Rubens—particularly during times of global strife or conflict. Groff updates this narrative to reflect present-day concerns by injecting her own twists into this historic and religious concept.

Teetering somewhere between utter turmoil and ecstasy, the contemporary female subjects in Groff’s paintings act as a conduit for prophesizing the end of the world. While Groff continues her depictions of antagonistic women, situated in the pastoral southeastern Pennsylvania landscape she calls home, this more insidious series finds the women possessed by the great unknown.

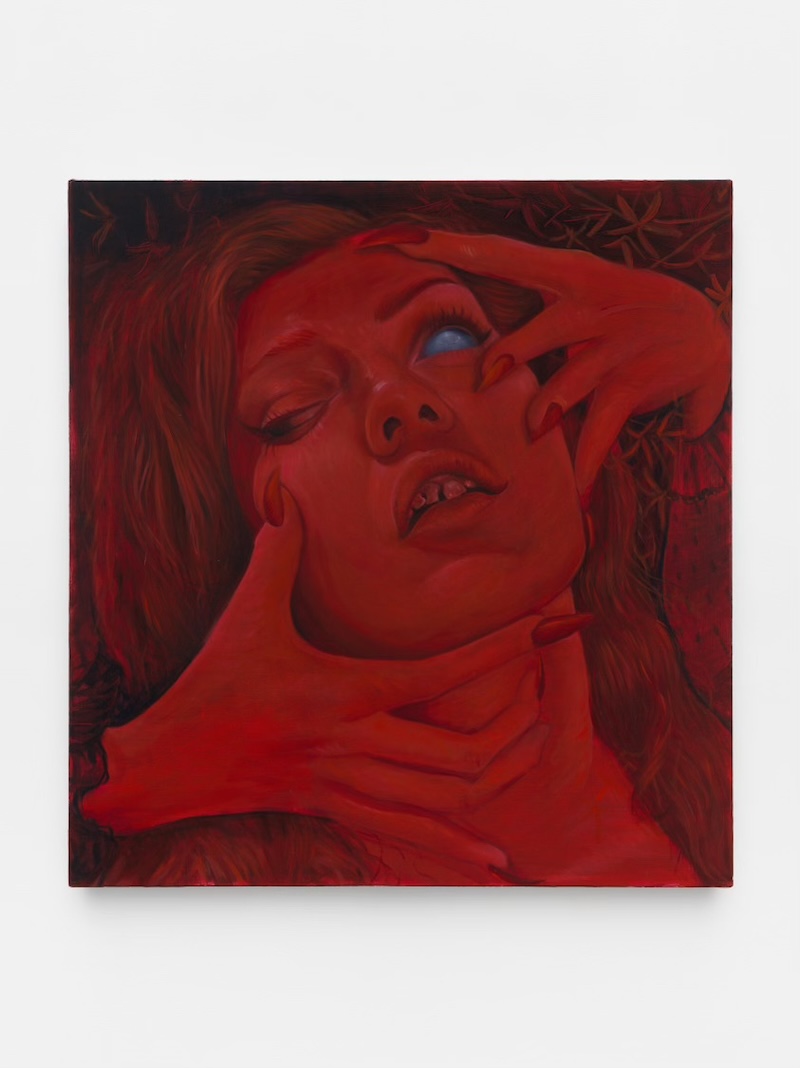

Color sets the tenor, with each painting offering a different kind of emotional transmutation of the fantastical. In Casting out Demons, Direct Contact (all work 2024), nearly the entire figure’s face, as well as a pair of hands propping it up, are drenched in red—a hue traditionally associated with evil and the provocative among Christian religions—while one eye glancing upwards appears to be elsewhere in blue. Though it is unclear exactly what has transfixed her, the figure appears to be locked in a battle of opposing forces.

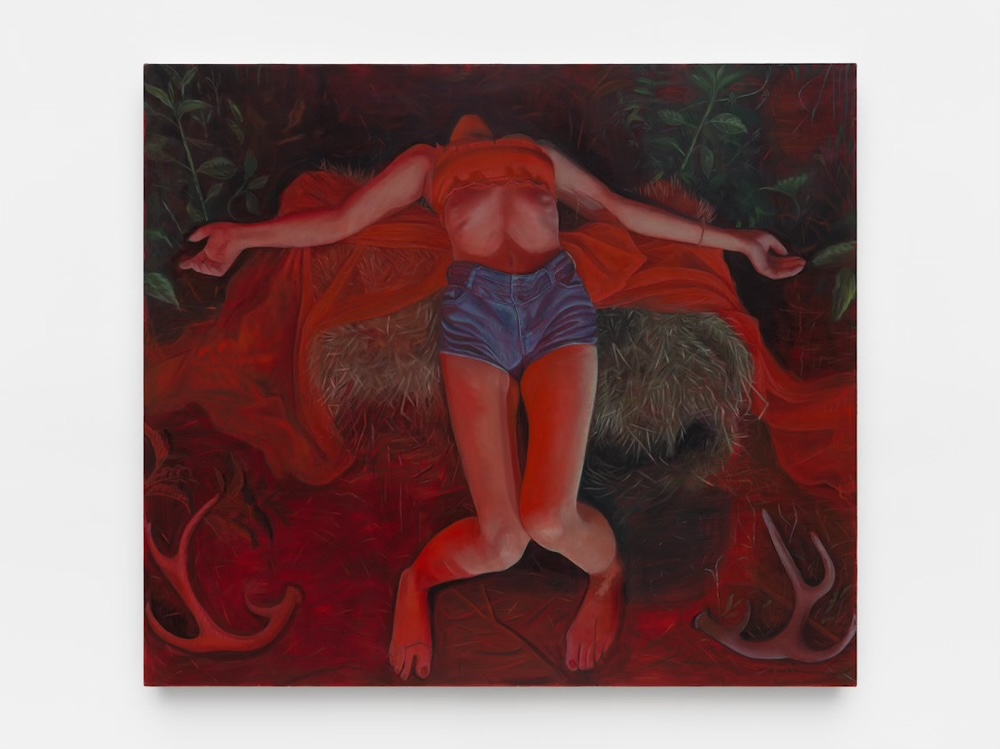

Bodies bent in unnatural contorted poses not only amplify the palpable tension of each scene, but further blur the boundaries between possession and ascension. Splayed out over a haybale with open arms, the lone female figure in Backwoods Pyre: Necromancer offers her body in a demonstration that mimics Jesus on the cross—a transitionary moment between life and death demarcated by both great agony and bodily transcendence.

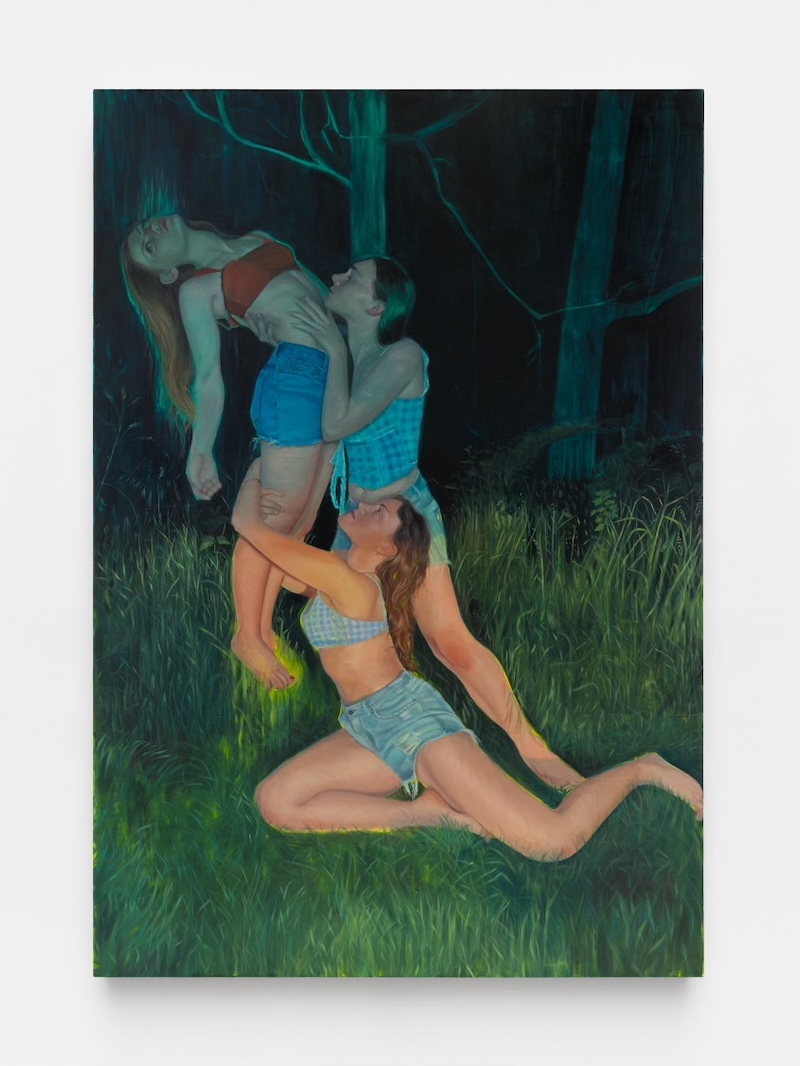

Perhaps the most explicit moment of disembodiment, however, occurs through a demonstration of rapture in which the living and the dead are transported and chosen to remain in heaven for being good. In Dark Pasture Encounter: Rapture, one woman appears to levitate as two others clutch her legs and waist in an effort to either go with her or keep her earthbound.

Noticeably absent throughout the works is a formal authority, such as a priest, who traditionally performs exorcisms. In a battle between the desperate and the divine, all the women take on the role of mediator by fighting these demons on their own accord, either internally or, in larger scenes where one person is afflicted, through restraint.

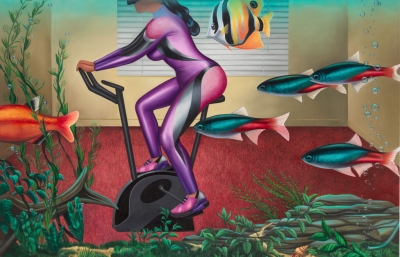

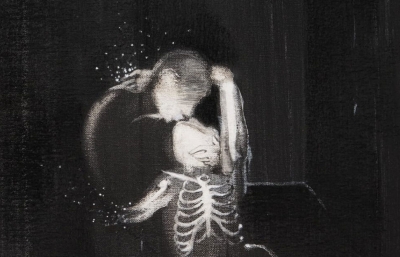

Teased in the title of Fentanyl Jesus, this may be the result of who or what these women are wrestling. While the scene recalls depictions of the Pietà—Mary’s sorrowful contemplation of her dead son’s body—the inclusion of the incredibly potent and highly addictive opioid in the title speaks to the chokehold of a different kind. Though their limbs are physically intertwined, each figure appears to have a singular experience of physical and psychological transmutation—one that taps into a harsh reality of rising deaths and despair.

Whether the figures are reaching a higher power, personal demons, or even each other, their need for both connection and escape serves as a kind of bellwether for the instability of our time. Their open displays of vulnerability and desire, expressed through physical touch and emotional transcendence, are ultimately underscored by questions of bodily autonomy and control. By creating a new kind of vision of events that could happen, rooted in her own working-class community, Groff captures a pervasive feeling of unease as she considers the ways in which we seek to subvert or overcome. — Francesca Aton, 2024