Titularly, with its citation of the genre of artist monographs, former Juxtapoz cover artist Nicole Eisenman's exhibition ‘with, and, of, on Sculpture’ at Hauser & Wirth's Paris gallery explores the artist’s multi-pathed approach to the medium. While Eisenman inhabits discrete studios for painting and sculpture, for her the two practices are deeply connected. (The distinction in loci could be described as ‘messy’ and ‘less messy’). This interrelation is most apparent through Eisenman’s drawings, of which she has said: ‘A line is sculptural, the way it floats in space on a white page. You’re looking at the representation of a dimension and it can be perceived as either two or three dimensional.’

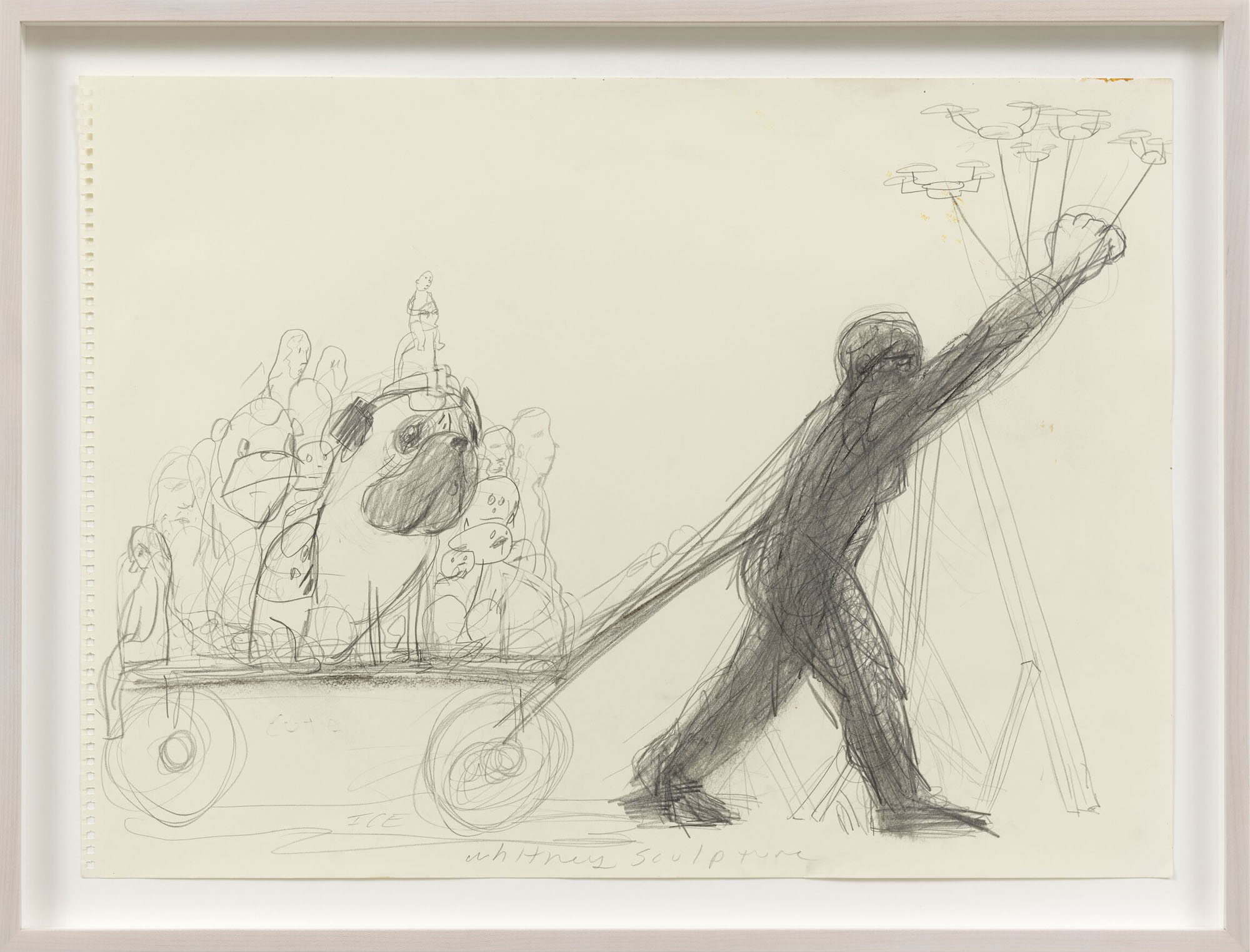

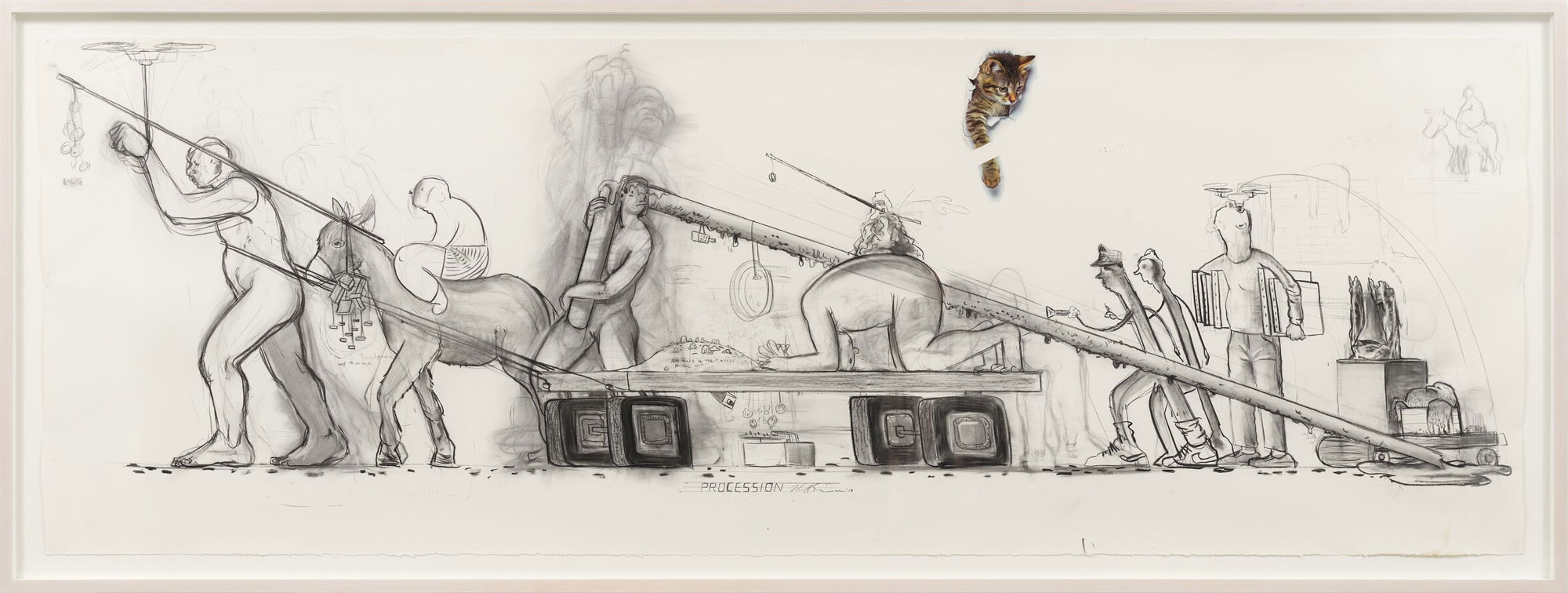

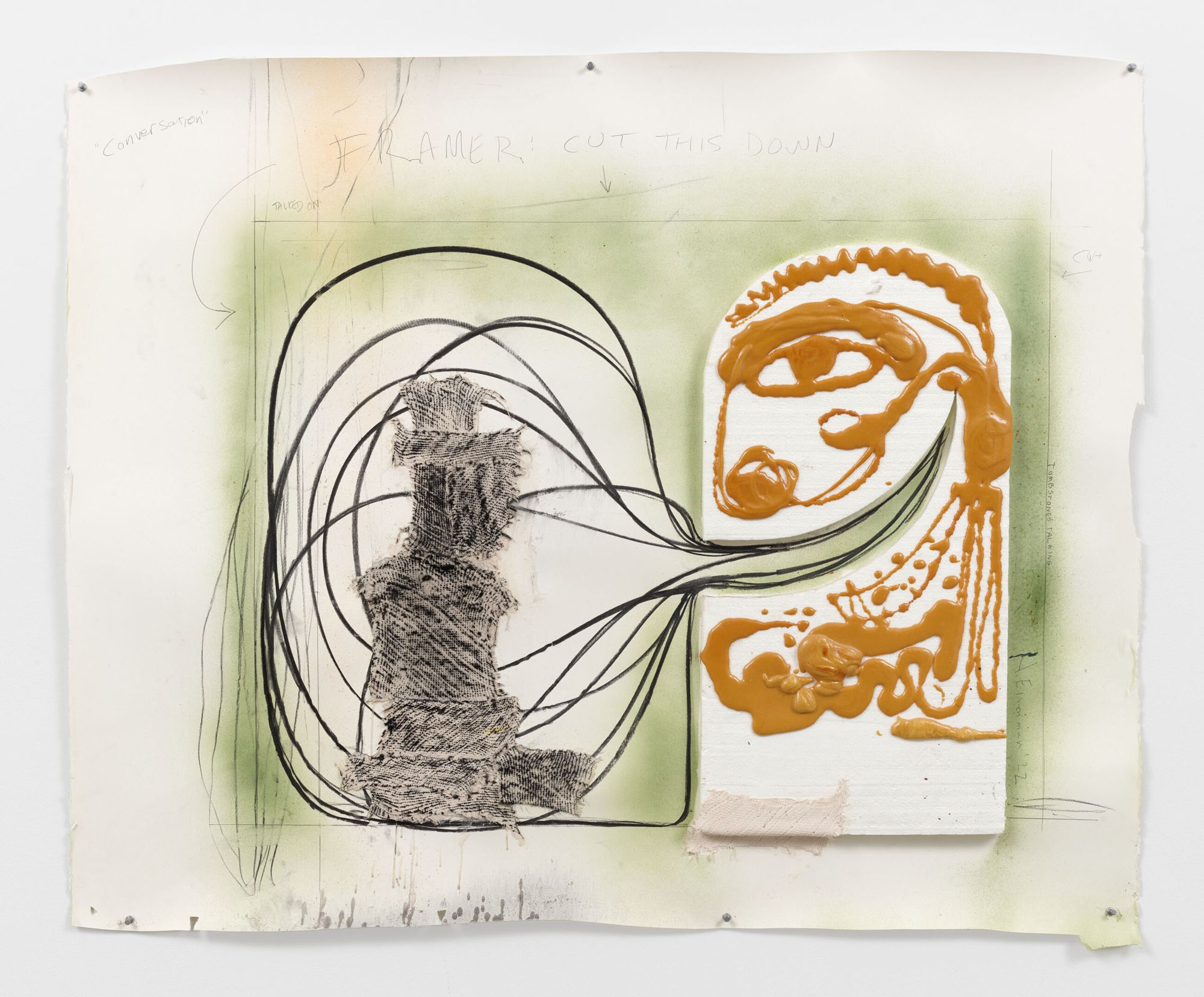

Between some works in the exhibition, the link is explicit: installed on the ground floor are two figures from Eisenman’s monumental sculptural installation ‘Procession’ (2019), which premiered at the 2019 Whitney Biennial, while on the first floor, a large-scale preparatory drawing for the installation is on view. The works, however, each split from their direct relationship. Downstairs the heuristic Junk Lady-esque sculpture on the back of ‘Perpetual Motion Machine’ (2019) is a direct result of both the environment of the studio and the technical concerns of the piece. Upstairs, the ‘G*d-cat’ in ‘Drawing for Procession’ (2024) pulls the work away from its practical function and defines it as a complete and separate thing.

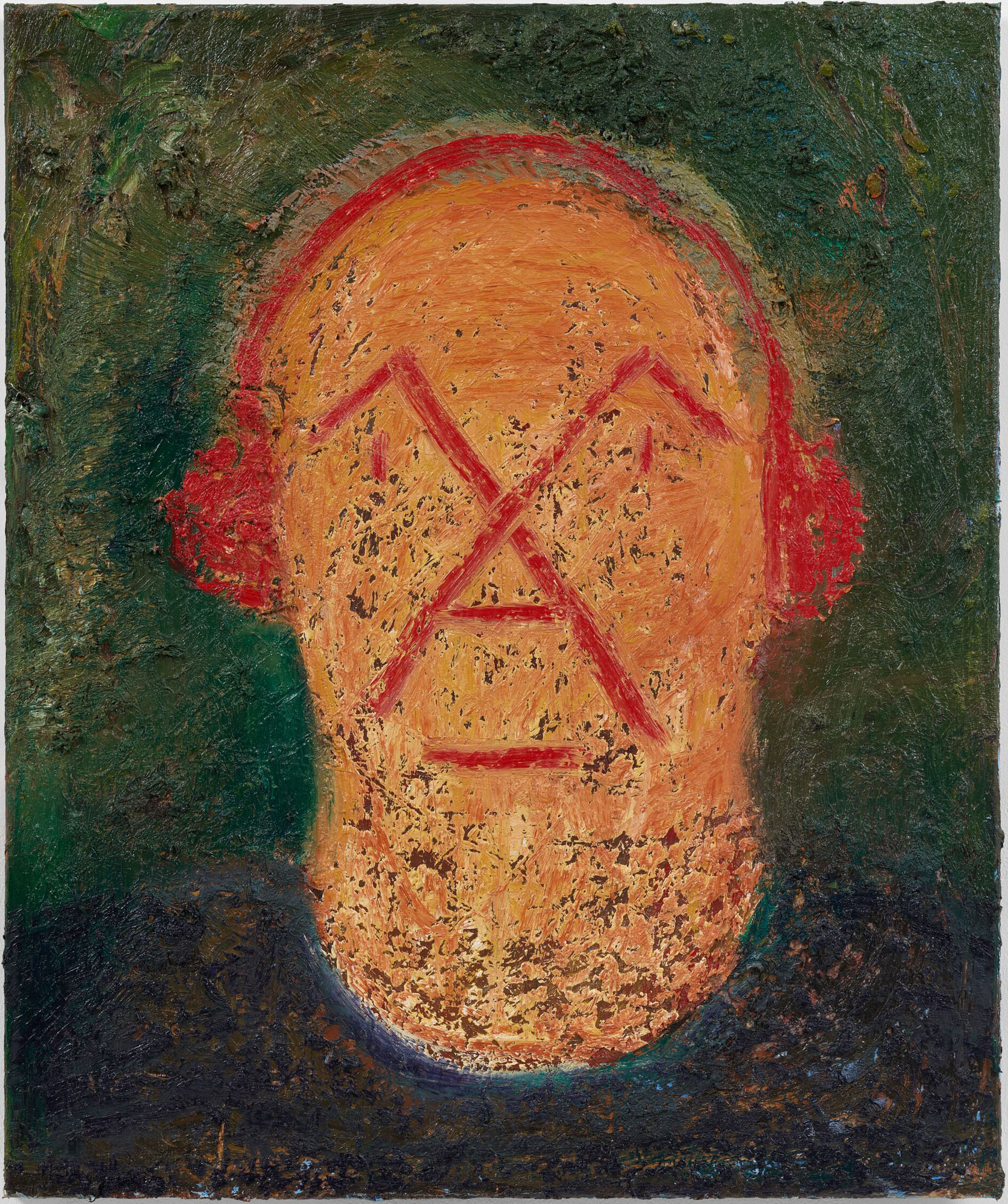

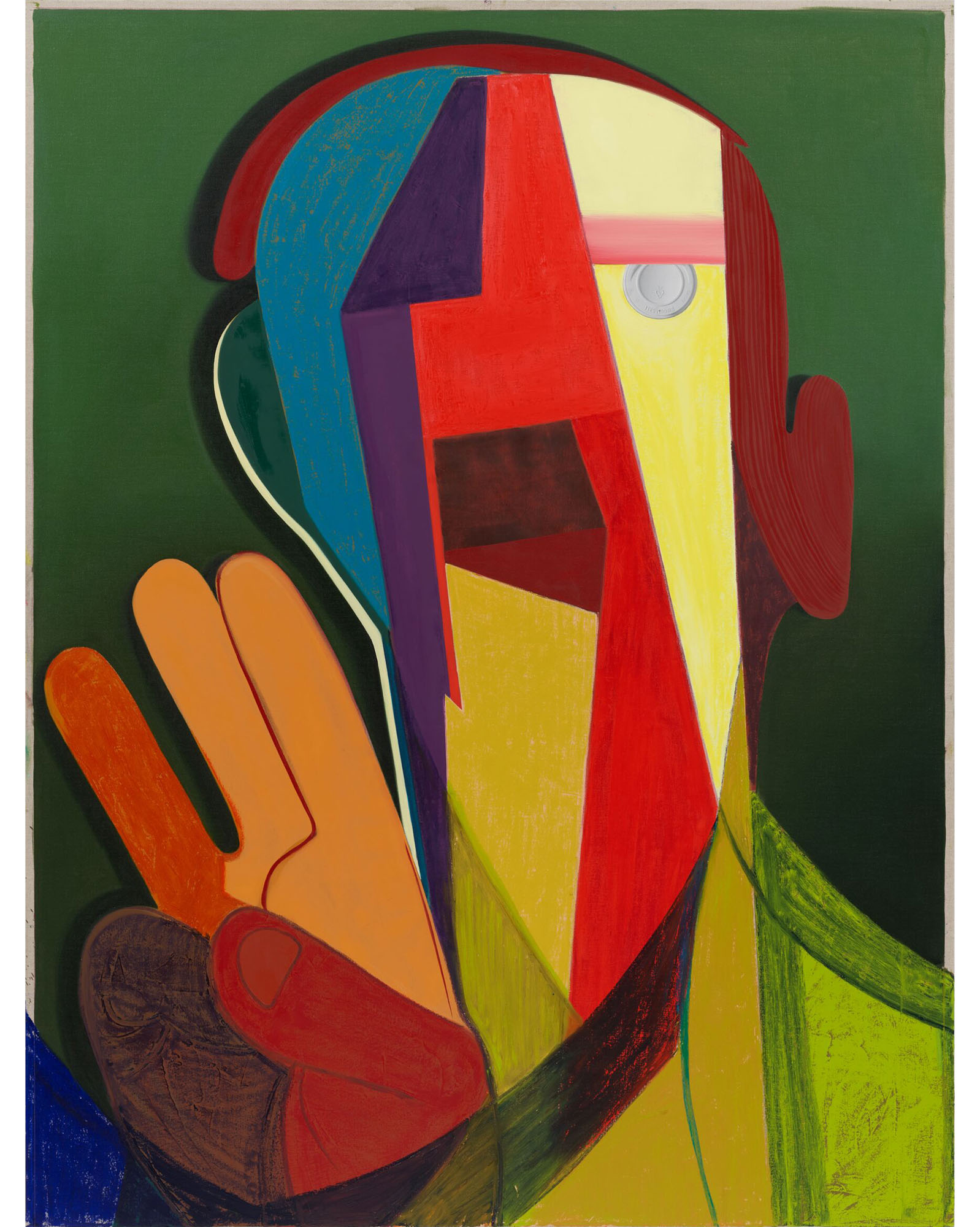

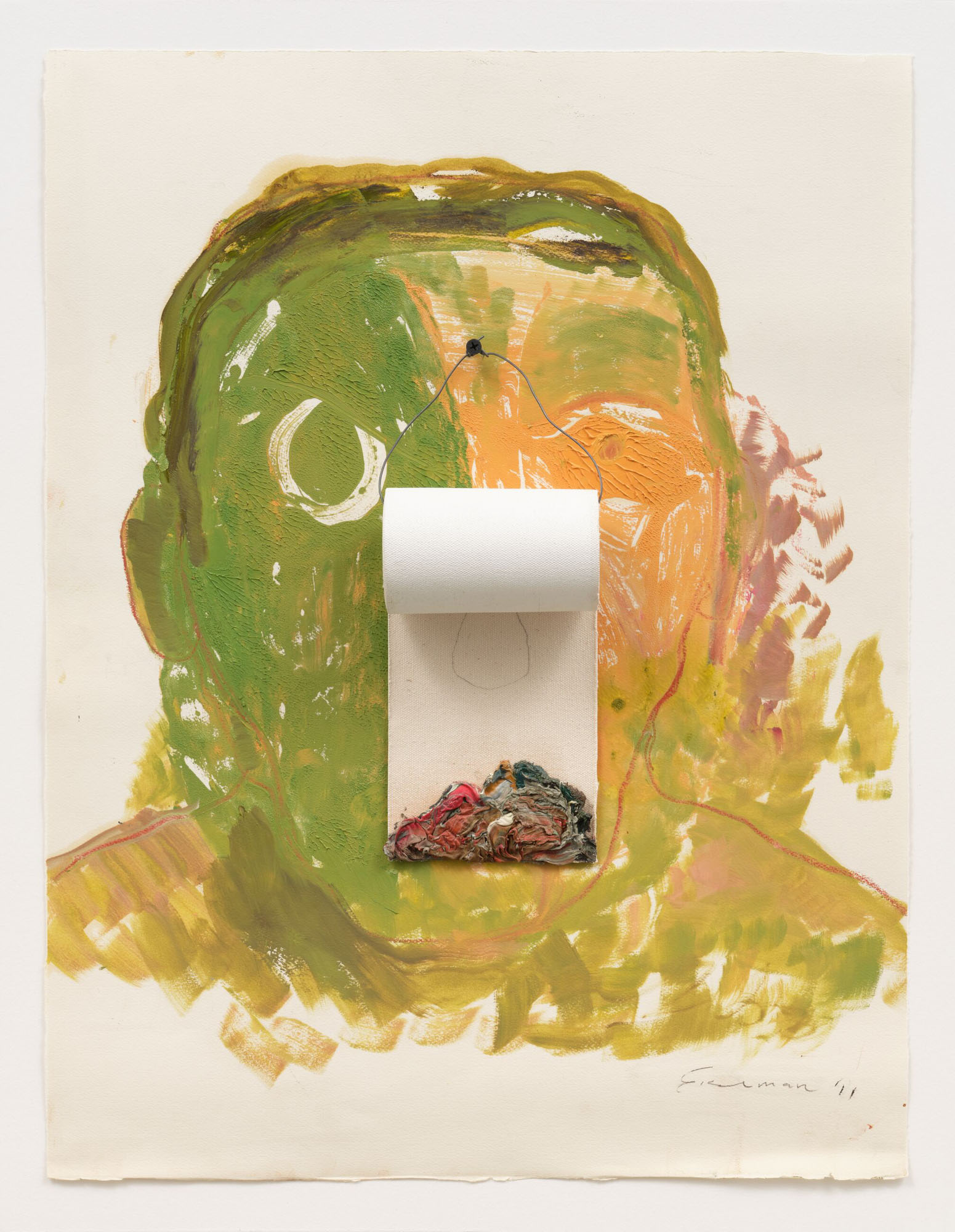

With other works the connection is established through process. Works in the series Shape Driven Heads are created via the physical act of painting, formal relationships building on one another, action determining reaction. Eisenman’s sculptural work often takes this approach as well. In ‘Head with Slab and Foot’ (2024), par exemple, the figure springs together from both found matter in the studio and elements sculpted in response to them. This piece takes the exploration of dimensional interexchange a step further by incorporating a plaster slab imprinted with an intaglio plate, corporally melding a twodimensional image, created in response to a three-dimensional structure, with a volumetric cartouche.

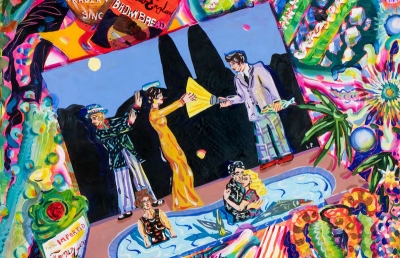

At the heart of the exhibition hangs ‘Archangel (The Visitors)’ (2024), a large-scale multi-layered painting depicting the vernissage of an imagined sculpture exhibition. In the work, Eisenman both paints fictional sculptures and, as the 20th Century would be happy to see, bodies in physical relation to form in space. One sculpture, not imagined, references John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter’s ‘Prussian Archangel’ (1920), a pig-headed military figure first exhibited at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920. Eisenman ‘installs’ the piece at the top of the painting, ominously suspended over the scene. ‘The Visitors’ in the work’s name is a reference to the same-titled 1981 ABBA single about the persecution of political dissidents. It could also refer to the figures milling about the gallery, the three menacing figures in the back of the room or the Archangel, redolent of the art historical narrative of otherworldly visitations.

The wide array of media in this exhibition perhaps most clearly and collectively demonstrates Eisenman’s remarkable ability for synthesis. As she moves between materials and forms, conversations started in one continue and transform in another. True to her artistic process, the distinctions between forms are more external than internal, derived from practicality of language. Situated between ‘painter’ and ‘sculptor’ Eisenman is maybe best described as ‘artist.’