"I thought that falling, which betrays us as absolutely human – our bodies slipping from an ordained position, failing to perform an expected pose or an expected role – could therefore be a form of passive resistance, a way to show complete humanity in the face of what is being expected by the world or ourselves," Louise Bonnet said on the eve of her solo show in Berlin.

Galerie Max Hetzler is pleased to announce Reversal of Fortune, a solo exhibition of new paintings on linen and paper by Louise Bonnet, at Potsdamer Straße 77-87, in Berlin.

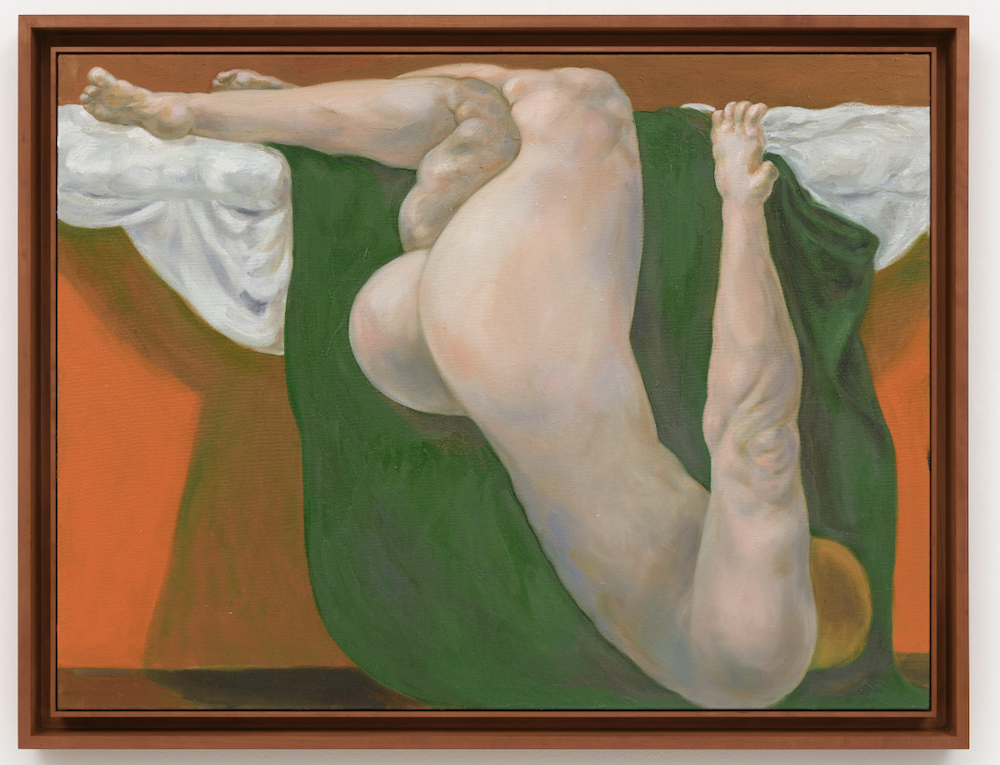

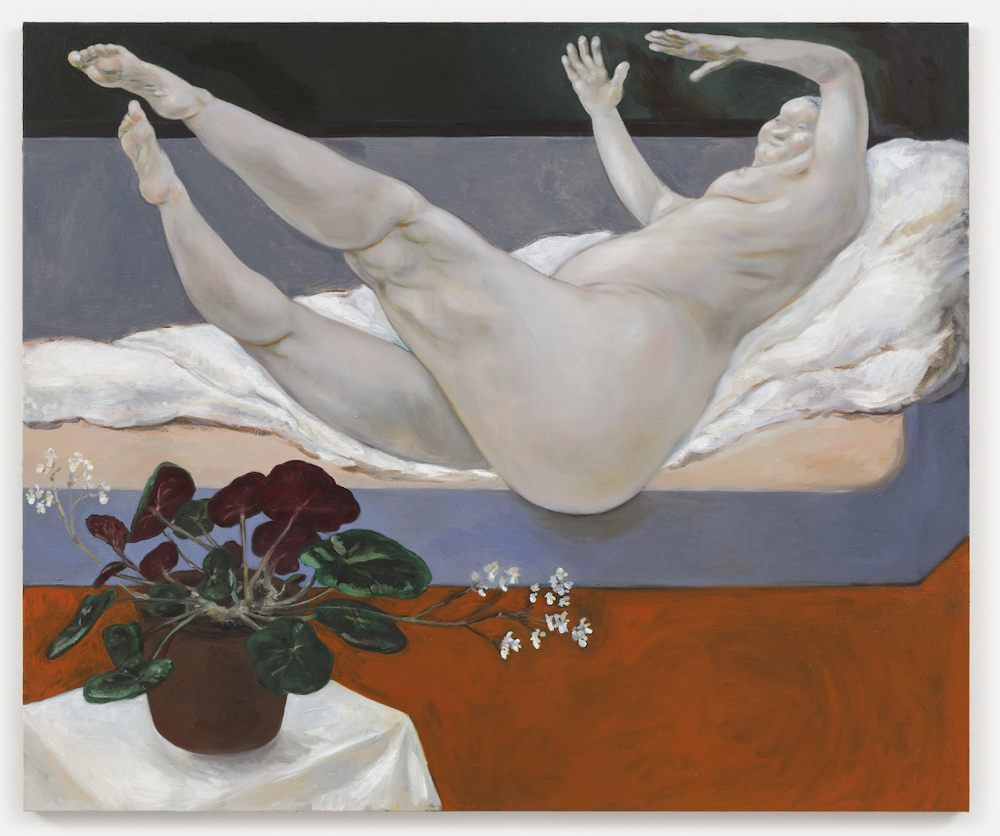

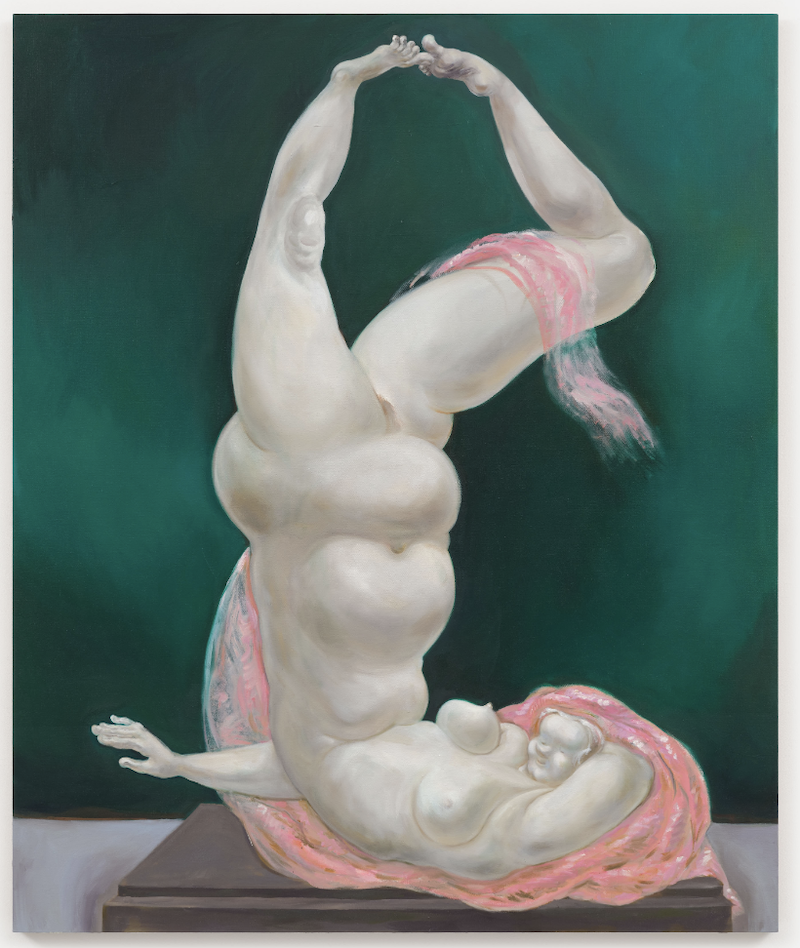

Internationally renowned for her emotionally charged depictions of the human form in unusual, often exaggerated poses, Bonnet explores difficult feelings such as fragility, melancholy, loneliness and grief in her work. The title of the exhibition, Reversal of Fortune, insinuates a plot twist or turning point that leads to both tragedy and a moment of catharsis. The works all revolve around the notion of falling. In the paintings we see female figures slipping off beds, divans or couches, plummeting from unseen heights towards the ground, gliding or toppling headfirst, and lying on the floor, after a fall from beyond the picture frame. Exploring the feeling of downward descent as a recurring idea, the works come together to represent all the different strands of meaning that unravel for the artist from out of this theme.

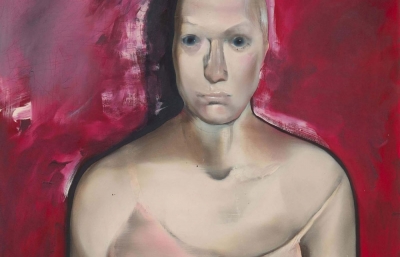

At moments, the act of falling is dramatic. In Asteria Red, the figure delves headfirst, the impact of the fall painfully visible on her distorted nose and strewn hair. The frailty of our human condition is made obvious in this work, through the danger inherent in daring to dance and the difficulty of maintaining balance.

Old Master painting has a strong influence on Bonnet’s work, in terms of theme and subject, as much as painting technique. Her practice of oil paint on linen creates a translucent layering of light and gentle flesh tones, reminiscent of Dutch 16th century painting. For subject matter, Bonnet is drawn to Pieter Bruegel, in particular his Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, 1560, which depicts a pastoral scene of people and animals going about their business. In the background, Icarus can just be made out by his flailing legs as he falls with a splash into the sea, so that for all our ambitions and search for power, the world moves on, indifferent to human suffering. The compositional elements of this source image appear in Bonnet’s A Splash Quite Unnoticed, where the legs of the protagonist are only just visible behind the still-life in the foreground. The title draws from a line in William Carlos Williams’ poem, When Icarus Fell, which was written about Bruegel’s painting.

Falling simultaneously offers the narrative of an escape, such as in the Greek myth of Asteria, the Titan goddess of oracles, constellations and falling stars. She herself fell to earth to escape Zeus’ advances, and the island of Delos was created where she came to land. In Asteria Pink, the artist seems to evoke the elongated grace of Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck, 1534–1540, emulating with distorted exaggeration the Madonna's stylised self-possession, her daintily bent hands and feet, and the flowing pink drapery which softly envelops her body. This mannered elegance is reminiscent of the slipping odalisques of 19th century painting, who were presented languidly reclining on their beds. Unconcerned with realistic proportionality, Bonnet's figures are similarly devised to fit the composition into which they are placed. In contrast to their historical counterparts, however, they convey a spectrum of emotion rather than an ‘idealised’ female form.

Bonnet’s love for symbolism is apparent in the inclusion of flowers in a number of the exhibited works. The artist depicts begonia, a symbol of warning or caution, black irises, signifying danger, and dahlias, which represent instability. In Dahlia, the figure falling off a divan gazes up at a bouquet reminiscent of the one in Édouard Manet’s Olympia, 1863. As in Bonnet's earlier work, the figures rarely look outside of the painting. The artist employs cinematographic techniques to let us gaze at her subjects unobserved, not in order to objectify but rather to find in their bodies a language for the emotions we suppress. While they are deeply rooted in art historical references, the works speak a universal language of embodiment, bringing a renewed perspective on the delicate tensions within ourselves. Bonnet’s work continues to resist easy categorisation, instead inhabiting a space of careful consideration and restraint, where narratives are felt rather than told.