Galerie Eva Presenhuber is pleased to present Planet on the Prairie, the gallery’s third solo exhibition by Iowa-based painter John Dilg. A river is flowing through a rugged terrain. The land is hilly and vegetation sparse, but not inhospitable. The water is clean but appears brown because the soil is peaty. The stream is fast and roaring, racing down the hill and over a waterfall that drops into a dark pool. Froth is forming on its surface. The greenery is northern. You can see ferns and some deciduous trees. The time is autumn. Frost hasn’t set yet, but the anticipation of winter is already in the air. There is a large tree overlooking the river.

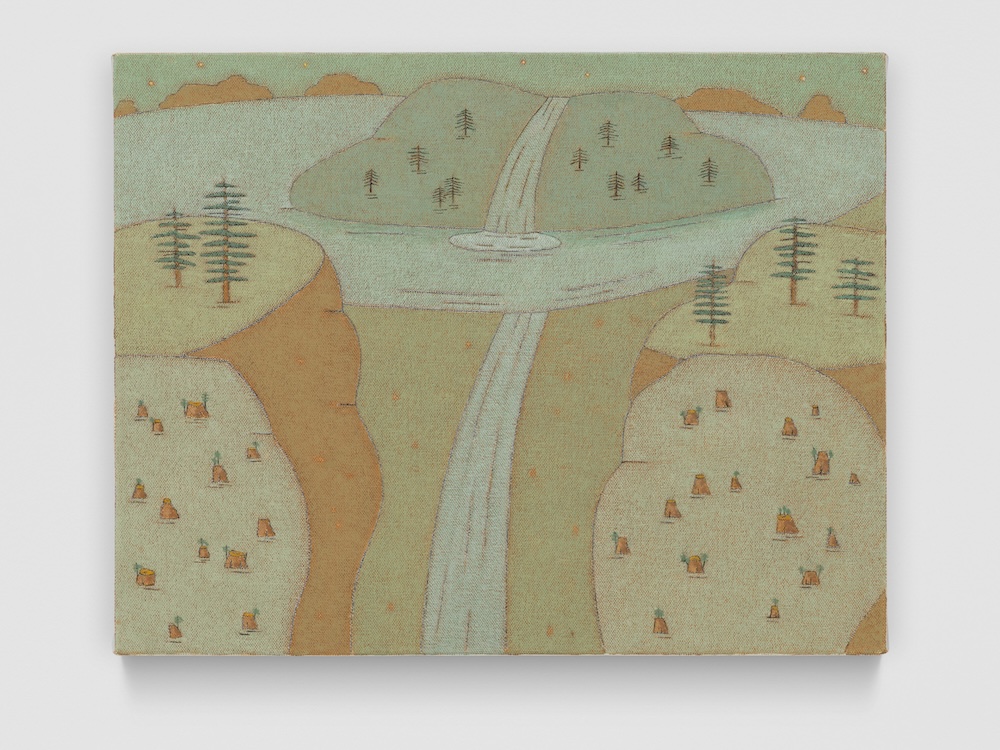

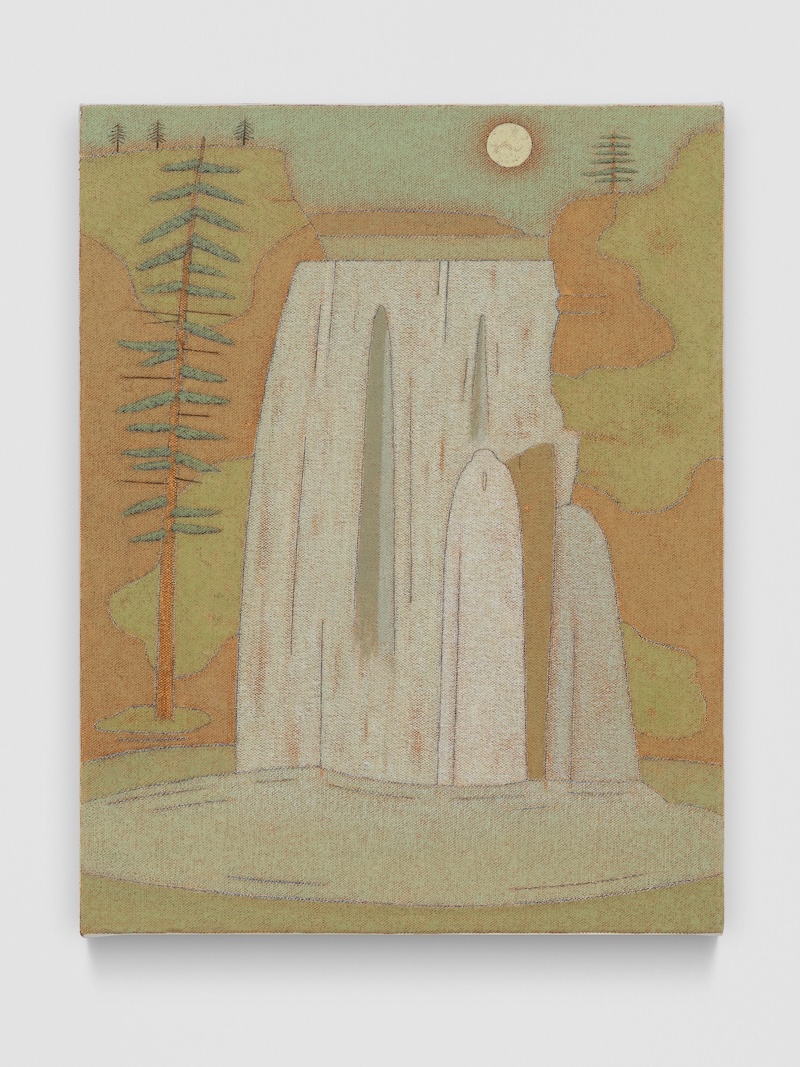

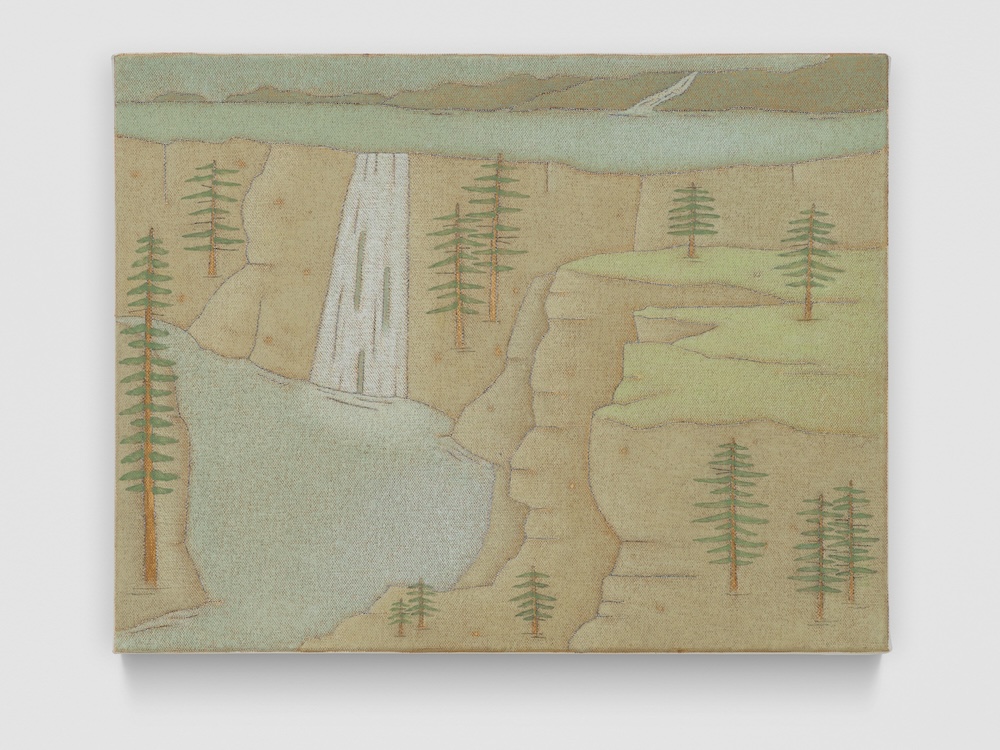

The above describes the scene set by Inversnaid, a poem by the English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889) written after his visit to the Scottish Highland (“burn” is a stream in Scottish). But it could very well be a description of a painting by John Dilg, Nine-Mile Falls for instance, with a waterfall dropping into a dark pool, rock-strewn hills and northern plants. While Hopkins and Dilg come from significantly different time, place and society, the worlds they depict rhyme in certain ways.

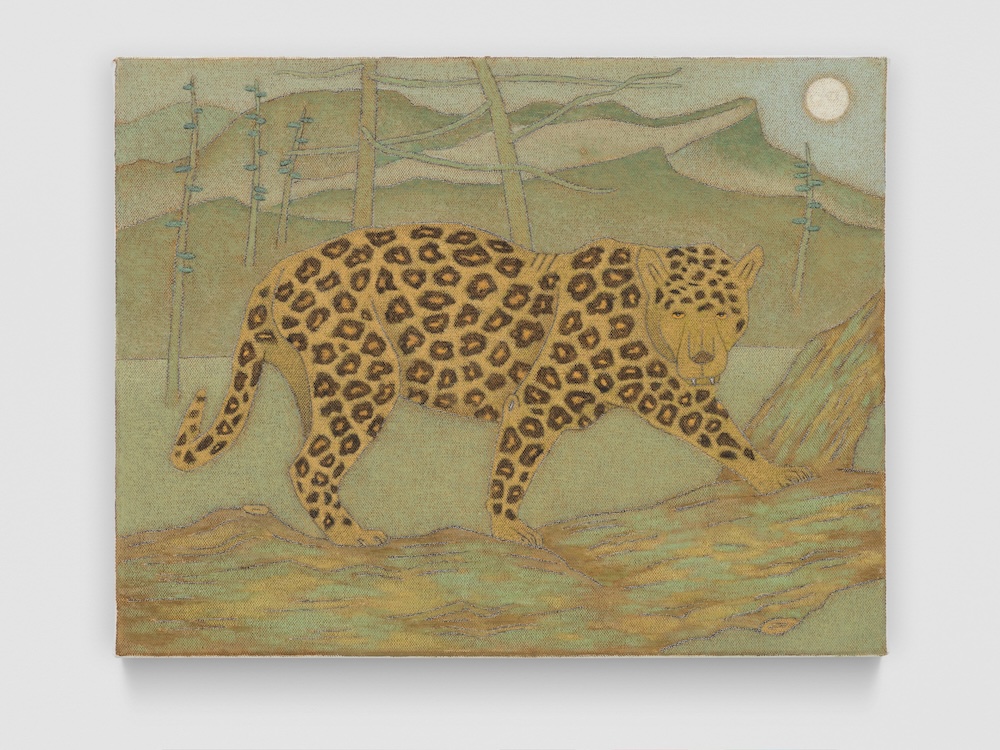

The nature in Dilg’s paintings, and it is always nature, never cities, is wild but tranquil, not arable and clearly not cultivated, though occasionally scarred by felling of its trees. Usually the only movement is that of the water. Always nocturnal, windless. Stillness pervades, but it is far from being lifeless. Though animals and people only make rare appearances, the landscape feels charged. The stillness is not that of death, but of dream. Temporal respite from all the hassles and coarseness of life. Take Copper Canyon. Behind its seemingly frozen calmness, one can sense life teeming beneath every tree, in every crack of the cliff, and under the inscrutable water. Life in Dilg’s paintings is mostly invisible but palpable current.

Yet, despite such charged atmosphere, there is also unmistakeable sense of resignation. But one cannot be sure if that is because Dilg is showing us the world recovering from a man-made catastrophe, or he is presenting an alternative state of the world that never experienced our destructiveness, the world that could have been but never was. Pieces such as Looking Through or Eternal, where new signs of life are sprouting out of the stumps of felled trees, suggest the former, while works like Nine-Mile Falls may points to the pristine nature of the latter. There is discreet hopefulness for the resilience of wildlife in both scenarios, but we are almost completely absent from them.

As mentioned earlier, the nature in Dilg’s paintings, and also that in Hopkins’ poem, is not cultivated. In pre-modern English, words such as wilderness, wasteland or wildlands simply meant any area that is not farmed. Architectural historian Vittoria Di Palma for instance writes that in medieval English, the term wasteland “included forests and chases, heaths and moors, marshes and fens, cliffs, rocks, and mountains”. And the word wilderness is derived from Old English wildēornes, meaning ‘land inhabited only by wild animals’. There is clear affinity between the states these classical words indicate and the landscape of the ambiguous world Dilg paints, where it could either be far, far in the future, or it is a dream of the places we never ravaged. There is a peculiar sense of timelessness, which allows a viewer to reflect on the age when the nature was wild and unknowable, the time language and landscape knew no modernity, and speculate on the world that left modernity behind, at once. In Wild Life, even a jaguar has returned. They used to roam as far up north as Colorado. Or maybe they never left the world of these paintings. And jaguar is a dappled thing, one of those creatures whose complex pattern revealed, for Hopkins, the innate and overwhelming beauty of the world.

Hopkins believed that every natural object and lifeform possesses its own unique internal order which organizes the vital energy it is imbued with. He called this order inscape, in contrast to the landscape of the external world, the world in which myriad beings, each with its own perfectly individual inscape, coexist in a delicate harmony. It’s a worldview infused with boundless vitality, the bouncing sense of liveliness he tried to capture in his idiosyncratic meter, but under constant threat from human destruction. While Hopkins’ understanding of nature was underpinned by his religious belief, which explains his limitless enthusiasm for all creation, Dilg portrays the inscape of his subjects with the sober acquiescence of our secular time, where we must confront the planetary scale harm we are causing. Or could it be that what Dilg paints is the same world Hopkins saw, but at night? The animate nature ruled by the moon? —Yuki Higashino