Along with Ludovic Nkoth's solo show, François Ghebaly in Los Angeles is also hosting another one of our favorite shows at the moment, Jessie Makinson's Something Vexes Thee?. The show presents new paintings by London-based Makinson.

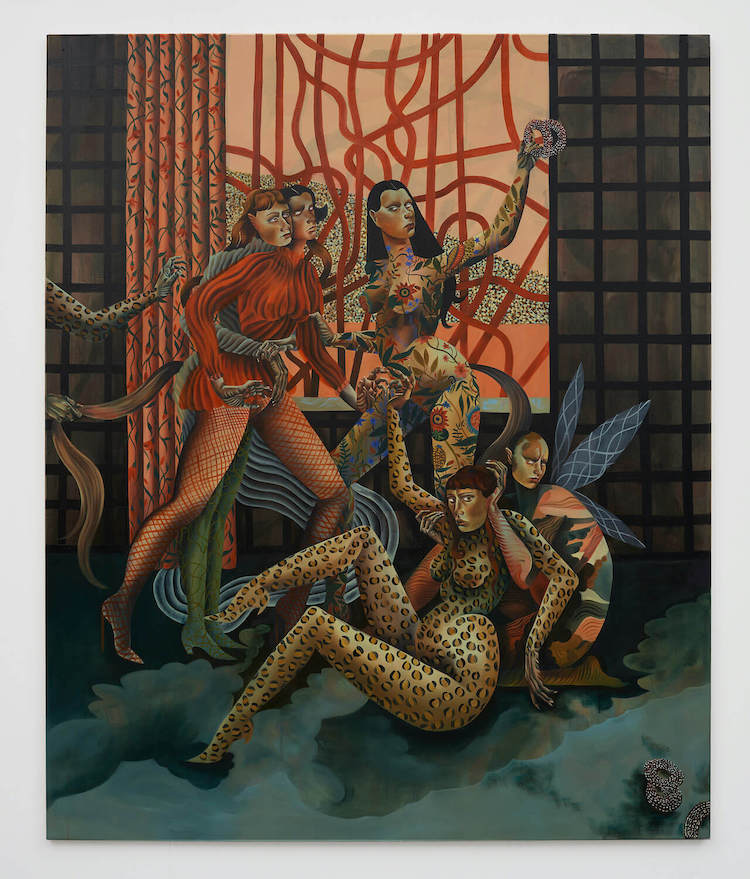

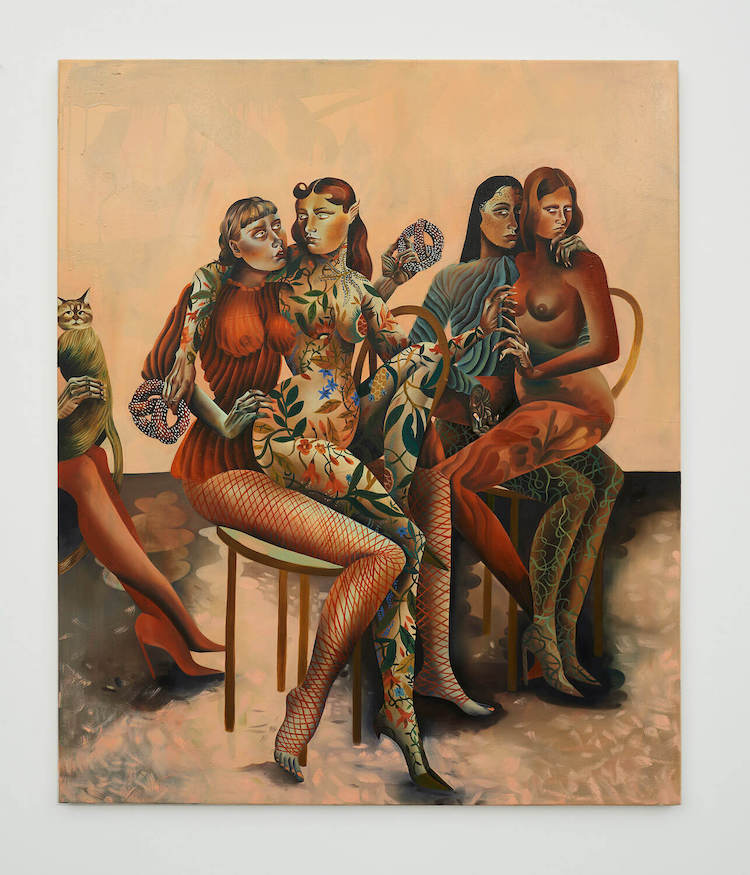

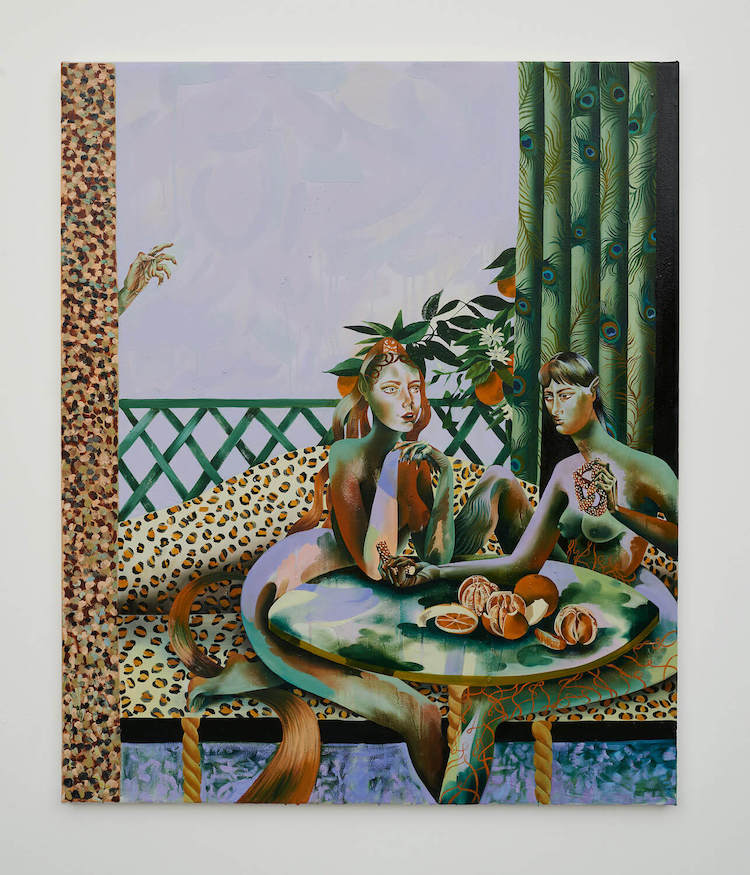

Take a royal portrait and gum up the seating arrangements until no one knows who is supposed to go where. Rearrange the furniture. Remove the men. Dress the remaining characters in scarlet fishnets and creeping vines, leopard spots and peacock tones, pleats of impossibly sheer fabric that whisper over the body (one wonders if it is fabric at all, or something more organic, otherworldly). Add pretzels, oranges, champagne, tarot… Suddenly the eye is free to roam the picture plane without a map. Stuffy courtly values of grace, elegance, and authority are subverted by the glamour and energy of the canvas. A court with no hierarchy..

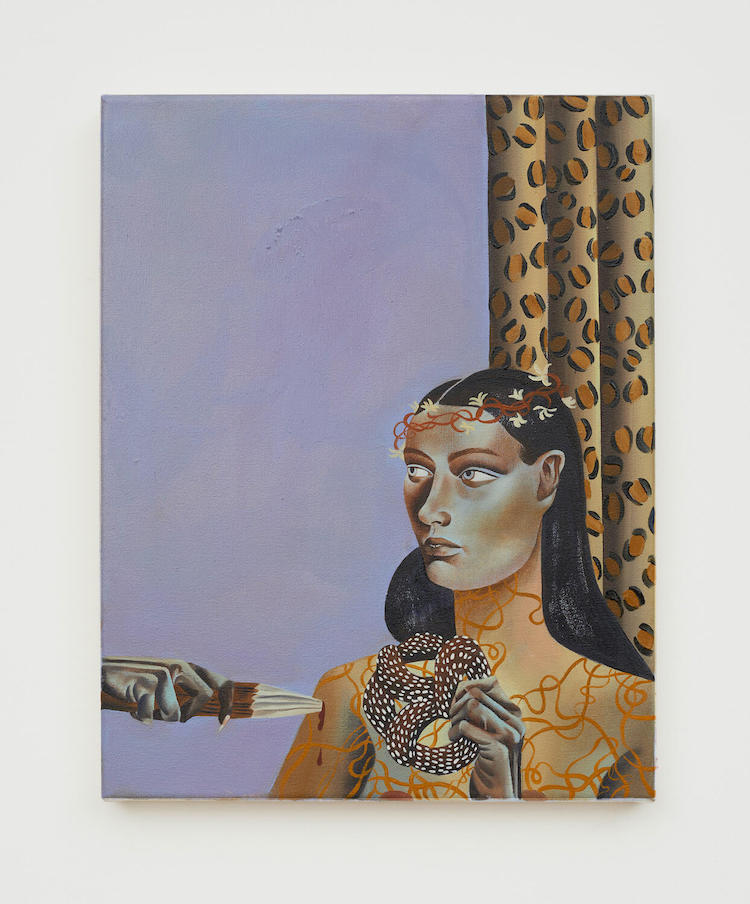

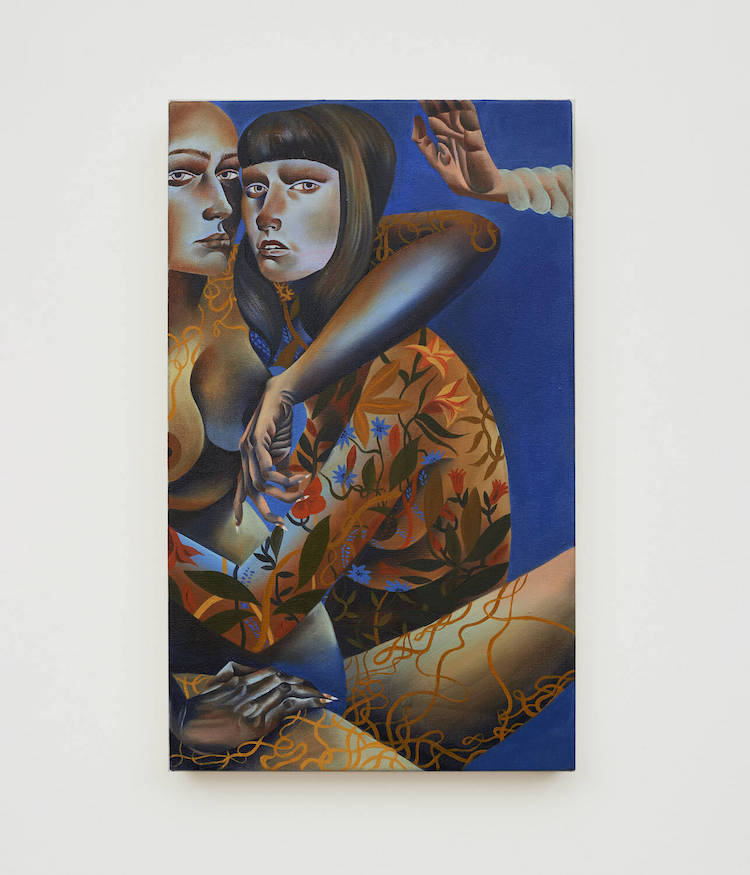

Jessie Makinson’s paintings are funhouse mirrors of historical and literary references, reflecting these allusions askew. There are 18th century brothel scenes and Georgian parlour games, ancient folklores and contemporary eco sci-fi. The titles of her works come from similarly diverse and diffuse sources; overheard snippets of conversation, quotes from cooking shows and 60s novels, anywhere really, and often taken out of context. Figures twist, bend, sit and splay at uncanny angles across unstable grounds. Their cool stares suffused with puckish ambiguity, simmering schemes, latent desires.

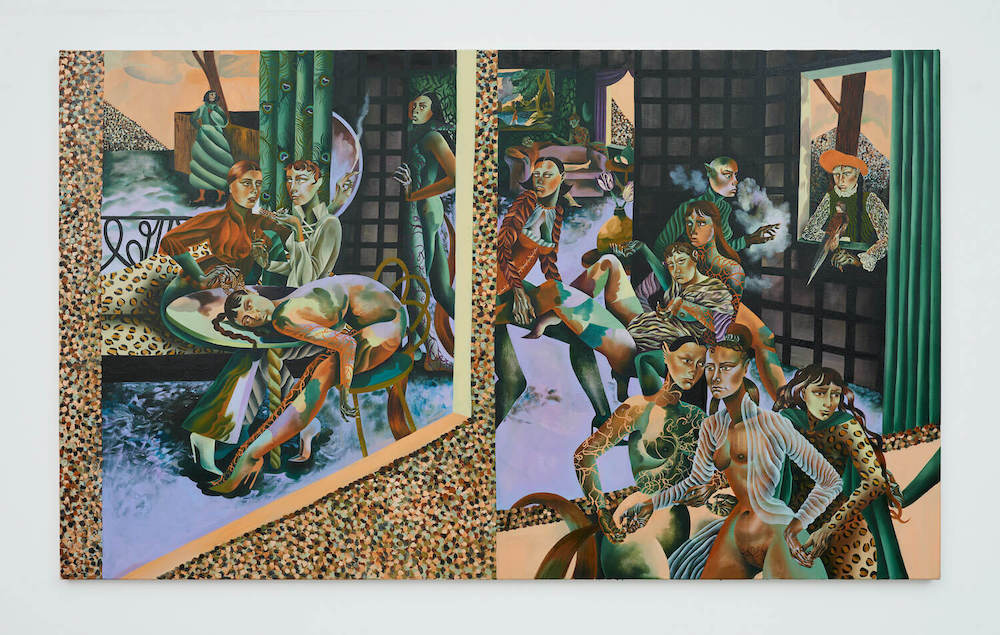

The title of the exhibition, Something Vexes Thee? is a rhetorical question, at once sarcastic and decorous. It’s what’s up with you? wrapped ironically in genteel robes. It is also what the witch asks of The Sheriff of Nottingham after his plans have been foiled once again by the trickster Robin Hood in the 1991 film adaptation of the English legend. Makinson’s painting of the same name is a decentered diptych crawling with potentially vexing vignettes. A couple of fighting dogs have upset a basket of peaches, a parlour game in a backroom equivocially suggests sensuous and sinister play, various limbs jut in and out of frames and doorways, suggesting narrow escapes. Along the right foreground, where painters traditionally place a repoussoir to gently guide the viewer’s eye back into the composition, the eyes of a steely, nymph-ish character gaze back at you over a crooked arm, annoyed, perhaps, at the intrusion. Makinson reimagines the hierarchical grid of the painting into a complex and generous container for many stories at once..

In her essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” Ursula Le Guin explains how the vessel, as opposed to the weapon, is the earliest and most significant “cultural device.” What has been gained, she asks, by characterizing history as a spear, an arrow, a sword piercing lines of victims and losers that span the centuries? What if we see the human story as a container, a sack, a vessel allowing for the jumbled freeplay of many narratives at once? Jessie Makinson takes this as an invitation to muss up the fixities that haunt historical painting. Instead of villains, heroes, or even genres, she offers story—not as an escape from reality, but as a tool for imagining a new one.