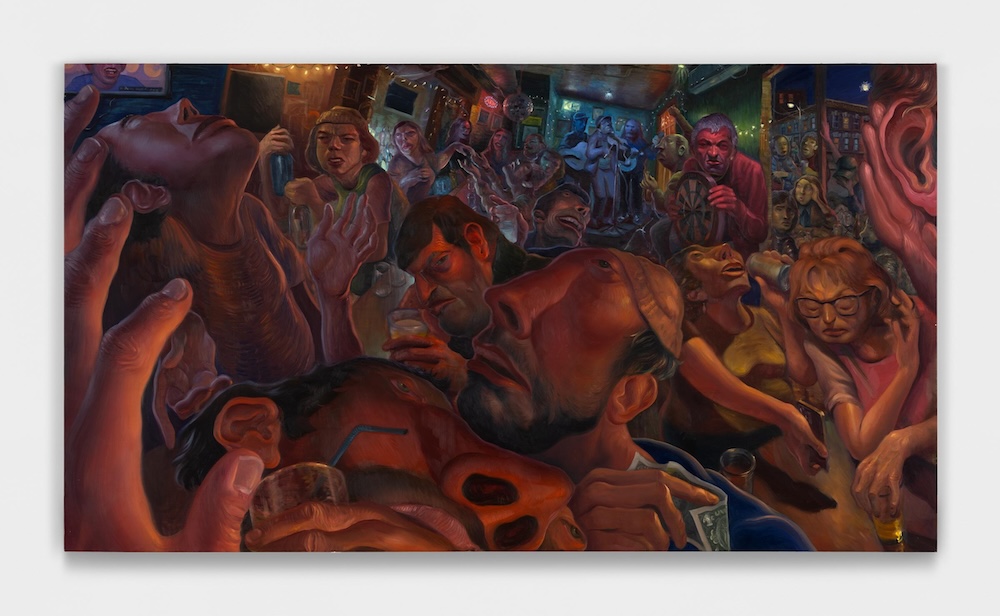

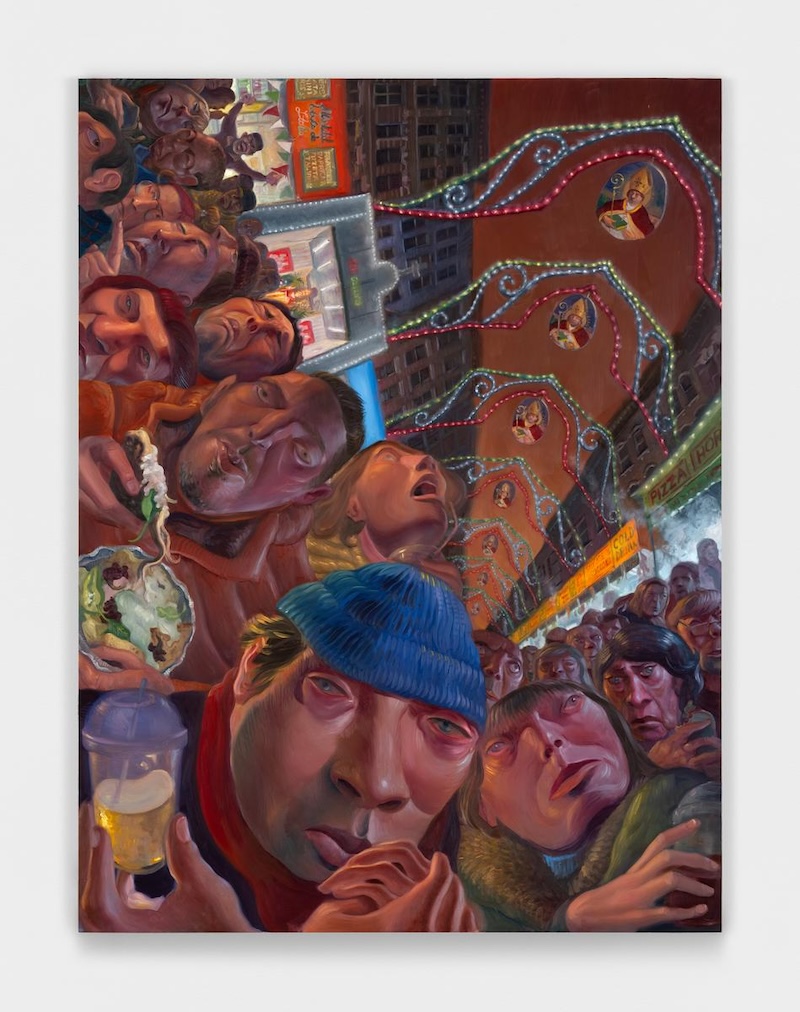

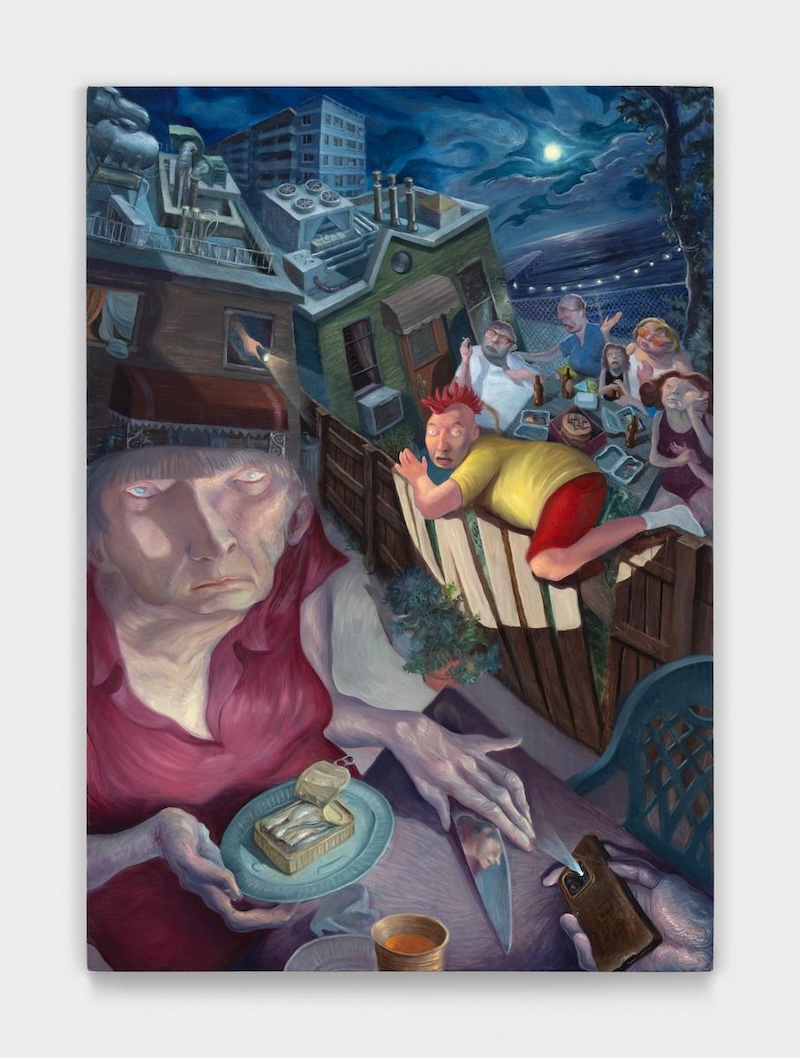

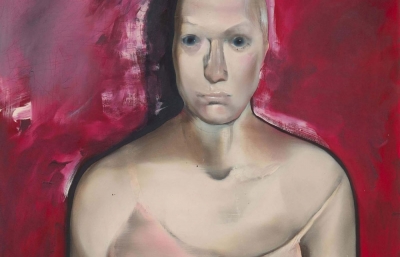

Harkawik is pleased to announce our solo exhibition with Guillermo Serrano Amat, his first in the United States. Born in Salamanca, Spain, in 1993, Serrano Amat has, for the past two years, called New York both home and muse, constructing in paint a sort of parallell reality to his own, one that allows his singular perspective to flourish. His palette is borrowed from the proponents of the Neue Sachlichkeit; his perspective from Terry Gilliam. He makes extensive use of formats more common to 17th century Mannerism than to contemporary painting—long, winding apertures that allow action to emerge from the perspective of a distant interloper, unfurling across the picture plane with escalating verve, until it arrives crashing at our footsteps. Fundamentally, he occupies the position of the outsider, observing (and recreating, in exquisite detail) the minutiae of social encounters, reminding us of the grotesque and unwieldy aspects of human behavior and interaction, and the odd confluence of historical circumstances, ideals, and biological imperatives that connect gesture with meaning, physical attributes with desire, and proletariat with polity.

Serrano Amat constructs scenes that are as laden with art-historical references as they are with the logic of film. The Idlers is in fact titled after Chaplin’s 1921 The Idle Class, a short in which a game of golf serves to commingle the Tramp’s working poor with the nouveau riche in the performance of leisure. In works like Ridgewood Noir, a card game erupts in a ballet of hands, recalling the rooms of George Grosz, the visages of Christian Schad, or the work of American counterparts like Thomas Hart Benton, Ivan Albright, and Ernie Barnes. Moreover, we see the influence of Béla Tarr’s social cinema, Dario Argento’s kaleidoscopic film gels, Robert Bresson’s narrative ambiguity, and Jacques Tourneur’s psychological atmospheres. Serrano Amat’s faces are each rendered as though viewed at close range through a fisheye lens; thus, the subjective experience of each individual is thrust indiscriminately at the viewer. In this way, as he borrows from historical modes to compose and color these encounters, the anxiety invoked by the packed streets and watering holes that fill his paintings is a distinctly contemporary one; it is the anxiety of too many primary perspectives, too many individual subjectivities and needs to contend with.

The Idlers offers us scenes of great social conflagration, in which gestural action, its import uncertain, is allowed to carry away our attention, and, occasionally the contents of an unattended purse or beverage. The key to understanding these works might not be the obvious points at which bodies come together, but the places where the pictures themselves break down. There’s a figure lingering in the doorway of Introduced to the Family, his face comprised of just a few concise brushstrokes, a bluegrass trio in Ridgewood, their visages melting away into their instruments, as if the plucking of a banjo might pluck away a nose or mouth, and a malingerer in the window (the frame of which is barely more than a patch of raw canvas) whose wrist, neck and face seem to emerge from the same twisted stump, a patch of smoke in San Gennaro that is little more than the memory of a brush, dragged and twisted carefully across the canvas. Elements of black comedy may be attributed to the painter’s interest in the turn of the century Spanish literary movement Eserpento, and yet, these are unabashedly American pictures. While it is difficult to explore the notion of the American Dream without giving space for its myriad fallacies, injustices and myths, perhaps given our fractious political climate, we’d do well to notice the exuberance in Serrano Amat’s heterogenous masses, and to relish the dusty ideals of this nation of immigrants.