A friend remarked to me right as I was starting this project that it's our job to make the kind of work we wish we saw more of in the world. There is the field of American art and culture focused on offering momentary escape, and then there is the smaller field, focused on helping confront some part of our own lives. The former, though fine in small doses, is almost ubiquitous and has mass appeal. The latter is more rarely addressed, mostly because it's harder and also, less fun. Despite that, it desperately needs our continued attention and care. This was always in the back of my mind while making this work.

Thoughts on Painting

Pat Perry on his new exhibition at UICA, National Lilypond Songs

There is a certain kind of darkness that often goes unspoken, and there are feelings that are seldomly orbited as a topic. This three-year project I’ll tell you about was an experiment to see if some of that might transmit through the fabric of the landscape, personal shame, bewilderment, isolation—the same conditions that produce school shooters and evangelical carpet salesmen who give their kids signs to hold that say, “God Hates Fags,” and internet bullies, and real life bullies, and people who wear the red hats with the white writing, and also, each of us. We all live with a level of anxiety, not knowing much for certain other than eventually, as writer Robert Coover put it, “awaiting us all is a doorway into oblivion that we shy away from until, in pain and terror, we’re propelled through it into eternal dreamless night and forgotten.” When works of writing and art are absorbed in a way that shows someone else shares the same vulnerability in the same uncertain way, it can be life-saving, figuratively and literally.

My generation, disenchanted with religion, distrustful of leaders, raised in a firestorm of advertising, and delirious from the media flows of new technology, has been mostly left to fend for itself in searching for ways to make meaning. Our modern economy has had huge success in its ability to oddly enslave us in a pursuit of our personal impulses, rather than teaching us how to help each other figure out how to live more meaningful lives. In a media and cultural landscape favoring speed over contemplation, I’m happy to be mocked for making a bunch of paintings that were painted in a slow, sincere aesthetic, about what I felt to be subject matter often met or approached with irony or derisiveness. To put it another way, dedicating myself to the task of quietly sitting by the window, painting blowing trees, and dentist billboards, and storms, and birthday parties for a daughter with no friends was a refreshingly oppositional approach to the things that are ruining our world and insidiously tearing us away from remembering how to love each other. Because, in the end, if we choose to continue the culture that encourages us to ignore, or lash out, or indulge reactive impulses, we will lose our chance. If we choose to follow the format to which my generation has been conditioned by corporate marketing, all but imploring us that we deserve to indulge our most knee-jerk desires, we will be on track to live in a world where art disappears, and this moment in time will be a shadow that lives as a memory of squandered chance. David Foster Wallace’s comments about writers apply to artists, as well:

“The next real literary “rebels” in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Dead on the page. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point. Maybe that’s why they’ll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk disapproval. The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. Today’s risks are different. The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the “Oh how banal.” To risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of over-credulity. Of softness. Of willingness to be suckered by a world of lurkers and starers who fear gaze and ridicule above imprisonment without law. Who knows.”

Another important piece to note about this project is about the circumstances that influenced the imagery, and supporting works we wished to include in the exhibition; the sketchbooks and 35mm photos. When my previous work has been written about in the past, there has been a fair amount of focus allocated to the lifestyle that birthed it: hopping freight trains, hitchhiking, trespassing, and traveling around the country, living out of a backpack on low dollars. It’s not that I think that focus was wholly wrong, and it wasn’t totally unintentional. That aspect has been pivotal in shaping the perspective of my artwork, and how it might be an interesting commentary on how kids in my generation are living through and dealing with the forces acting upon us. It did often feel a bit narrow, however, like the sensational adventure aspect was a thin veneer that was continually being peeled off and showcased on its own. A lot of those years were spent trying to portray that we were a bunch of lost kids, but somehow living outside and above something; living outside and above a reality no one can escape. Nowadays, it seems more modest and meaningful to try to face that reality sincerely with a bit less judgement, and to try to find some communion or better ways of finding meaning, despite our failed attempts at completely repudiatiating a mass culture that most of us still very much despise, or at least take serious issue with. As writer Zadie Smith wrote:

“We already know US culture is materialistic. It can be expressed easily and doesn’t engage anyone. What’s engaging and artistically real, is taking it as axiomatic that the present is grotesquely materialistic, and asking the question; how is it, that we as human beings, still have the capacity for joy, charity, genuine connections; things that don’t have a price? And, can those capacities be made to thrive? If so, how? If not, why not? One way out of this bind is to see people as complex human beings, sensitive souls, able to plumb their own emotional depths, capable of interesting thoughts, despite the deadening times.”

What the prior information about past sensibilities and travel topics (or the lack thereof) has to do with National Lilypond Songs is the inclusion of the sketchbooks and photographs, and why curator Anne-Laure Lemaitre and I inquired into a connected but separate part of the exhibition space to show these. I filled up almost ten moleskines full of travel drawings and have hundreds of 35mm photos that could and should fill a role in acting as supporting evidence to the twelve paintings, as they were collected over the years leading up to and during the creation of the work. I jokingly used to label the sketchbooks, “Data from the Field,” and it would be reasonable to imagine including them with the work now that it is more of a multi-year thesis paper. Hopefully, showing the evolution from one sensibility to the other would serve to walk the viewer through the thought processes of the work in a more approachable way.

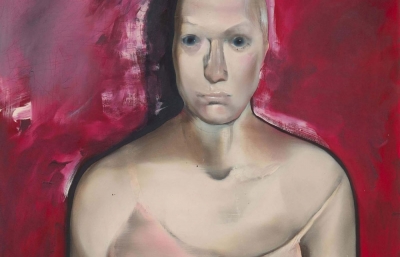

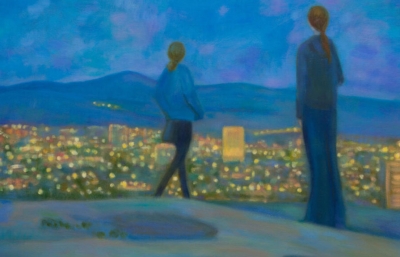

I feel that I’ve only been writing about this work in a wide orbit, but it feels impossible for me to bring myself to didactically explain the images and what they were supposed to be about. So, I’ll try another approach in inquiring about my hopes for how people view the work. It’s my hope that someone is able to see it and be reminded of their life in a way they might often overlook. This is not for lacking powers of observation, but because life is not and cannot always be conducted in a state of wondrous inquiry. There are pipes to be plumbed, groceries to be bought, energy bills to be paid, and mufflers to be replaced. If the art is effective in creating some pause at all, I’d take it as a small success. It’s not about these being some kind of apocalyptic portrait of what I think is coming, but more a personal acknowledgement to myself and others that what we are living through and foggily grasping to understand, takes a psychological toll in a way that’s specific to the present, but also spanned through all time.

The Lilypond parable is a hypothetical riddle that was used to teach French school students about exponentiality. There are lily pads in a pond, and the amount doubles each day. In 30 days the pond will be full, blocking all light and choking the ecosystem. On which day will the pond be half full? The answer is the 29th day. The 29th day is the day that it often feels to me that we’re living in; like we may be living at the late stages of a species whose development has outrun all others, and living in the late stages of a corrupt, divided country with an economic system commonly referred to now as “late capitalism.” The variety of reactions to the imagery of the paintings, as I’ve shown them to friends and peers in my studio over the past three years, has ranged from apocalyptic to locally familiar for others. It was my hope that the title reflects that difference in perception—deciding whether what we’re living through is an unprecedented beginning of our existential end, or if this is both reacting and trying to make sense of the simple and harder truth, that each of us alone will have to face that same, and ultimately, less consequential, existential end. So with that in mind, what matters? Maybe we ought to try to help one another lonesomely suffer through it a little less, and take notice of morning light on house siding, and rabbits, pile sculptures of couches, the way puddles reflect sky, the way dirt and snow sit on top of pavement, and how the view isn’t always bad between the highway and the ditch.

Pat Perry’s traveling exhibition, National Lilypond Songs, is on view in his hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan, at the Urban Institute of Contemporary Art, through January 25, 2019.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2019 issue