“Love is so sacred in a culture of domination, because it simply begins to erode your dualisms: dualisms of black and white, male and female, right and wrong. I’m a seeker on a path... a path about love.” So fully in sync with that premise, Mickalene Thomas embraced the title of bell hooks’ dynamic words for her first internationally touring exhibition, All About Love, showing at The Broad from May 25 through September 29, 2024. I spoke with curator Ed Schad about a truly vigorous invitation from Thomas to meet her women and become enveloped in a passage of portraits, collage, photography, rhinestones, and Love.

Gwynned Vitello: Let’s start by telling me how you got involved with this show.

Ed Schad: The show was initially pitched to Mickalene by the Hayward in London, and their director approached ours about it. I then took a meeting in London with Chief Curator Rachel Thomas, who had opened the conversation with Mickalene, and yeah, I’ve been on the project ever since.

It’s described as a touring exhibition, so would you describe it as a retrospective? I hope we see Lounging, Standing, Looking in the show.

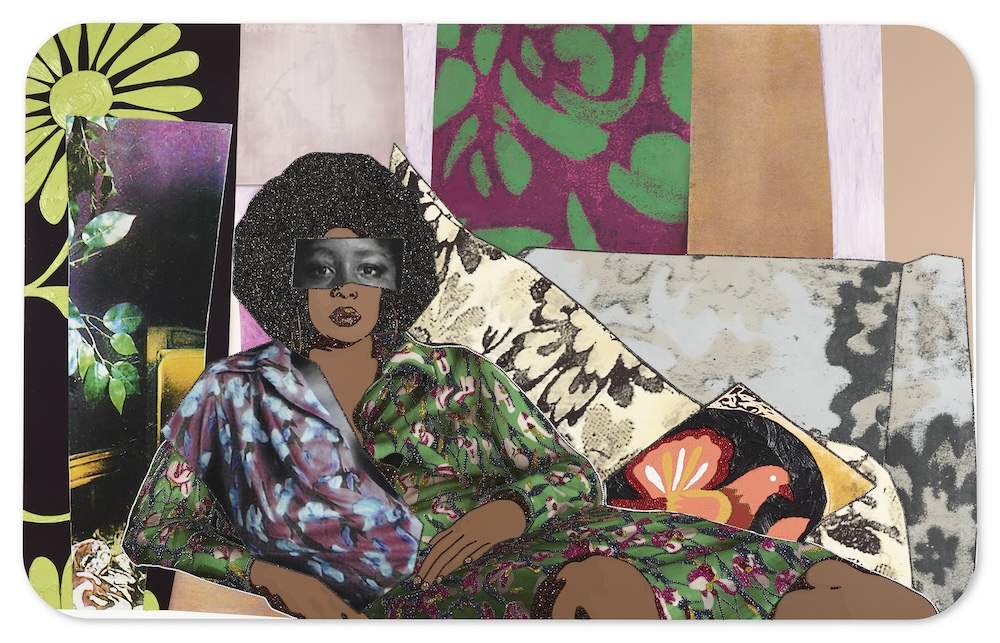

There hasn’t been an international touring exhibition. This show focuses on 20 years of Mickaelene’s work, and you do get your wish. Lounging, Standing Looking, from 2003, is her earliest work in the show, and there will also be pieces that are fresh out of the studio from 2024. So we have this wonderful arc from her career dating back to her postgraduate period right up to what’s happening day to day right now.

That’s great! Following up on how things began, I do wonder about the title of the show. When the idea was presented and you were all talking about it, was bell hooks part of the conversation, or did that come up later?

It came a little bit later. The show developed over many months, and the title was something Mickalene suggested, and I’m thrilled by the title, thrilled that we’re centering on bell hooks’ book. I’ve used that book quite often for my essay as to how we aim to present the spirit of the work.

I think it’s been on the New York Times best-seller list for almost a year, so I had to look up some excerpts and discovered that it’s a small book, but full of beautiful sensibility, perfect for this exhibition.

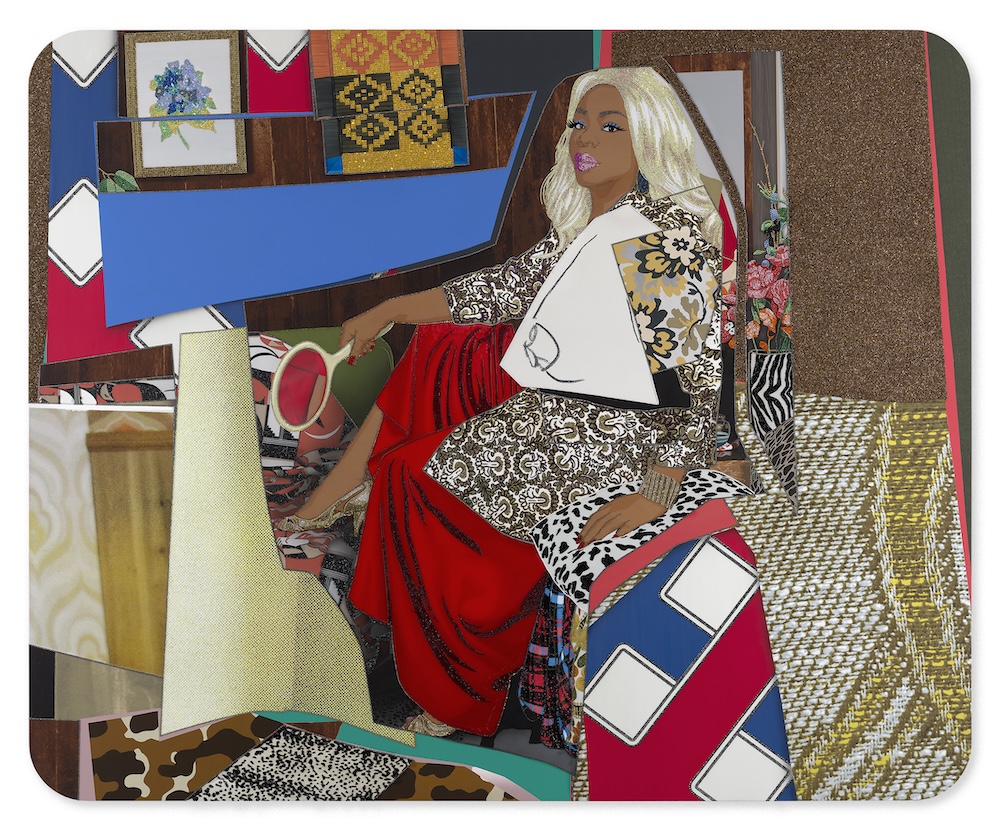

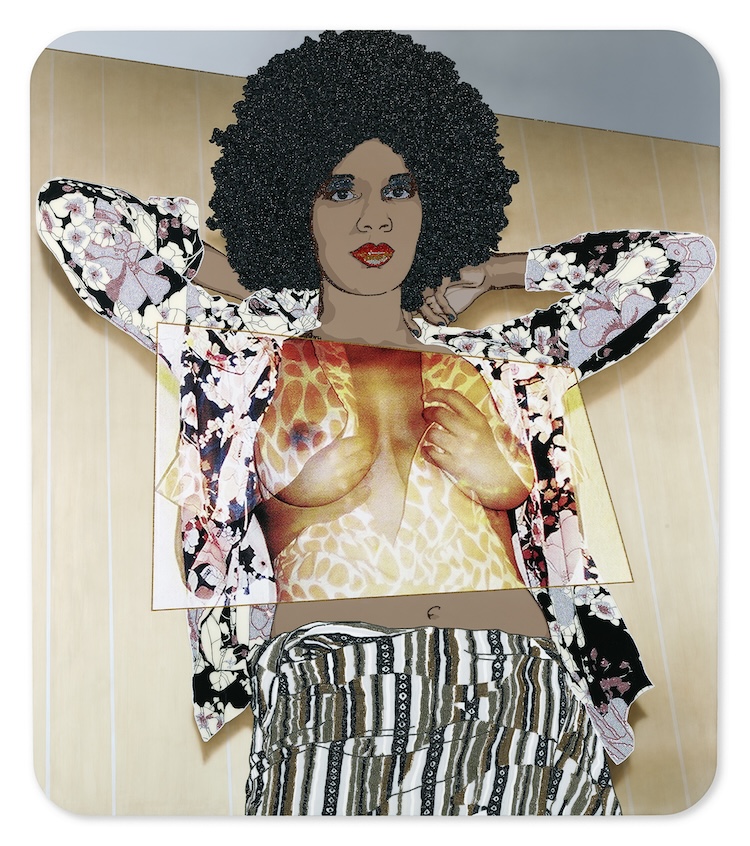

It definitely is. In my reading of the book, I think the chapter I’ve personally engaged with most is called the “Love Ethic.” I think that one of bell hooks’ arguments about love in that chapter is that the true engagement that love requires, which is often joyful (but always a task) is something that has to be recommitted over and over again. So Mickalene and how she approached her subject, whether it’s her mother Sandra or a muse like Din or Qusuquzah, it’s a level of engagement over the course of many years, even decades. As she returns to their images and repeats them, I really keyed on an expression the bell used about the ethic of love moving from state to state. It’s almost like printmaking, and I think that beautifully encapsulates the spirit of what Mickalene does as she moves a muse from making them feel comfortable in an environment into a photograph, into a collage, into a painting. And now, with recent works into a variety of mediums, whether silkscreen or dye sublimation print or neon or sculpture, it’s a matter of renewed engagement, renewed looking at people she cares deeply about. This is a bit wordy, but I think that’s the spirit. I fully expect the other partners to come up with their own interpretation of how the title intersects with Mickalene, but that’s the approach that I wanted to take.

Oh, I think the title is so important to this show: All About Love. It imbues all the work and you’ve expressed it really well. I hope quotes from the book are in your essay and the wall texts.

My essay references bell hooks, for sure and I expect it to enter the wall text, which I’m writing now.

Let’s circle back to the work and your connection with this show.

I don’t think Mickalene remembers, but I did a studio visit with her 15 years ago. I loved her work, and I loved her. Afterwards, I saw her show at the Santa Monica Museum of Art in 2012. I remember it vividly and reference it in the floor plan at the Broad. Then MOCA did a small show, referenced in the show, in 2016 called Do I Look Like a Lady?. So over time, I got to know her work.

Tell me about the show.

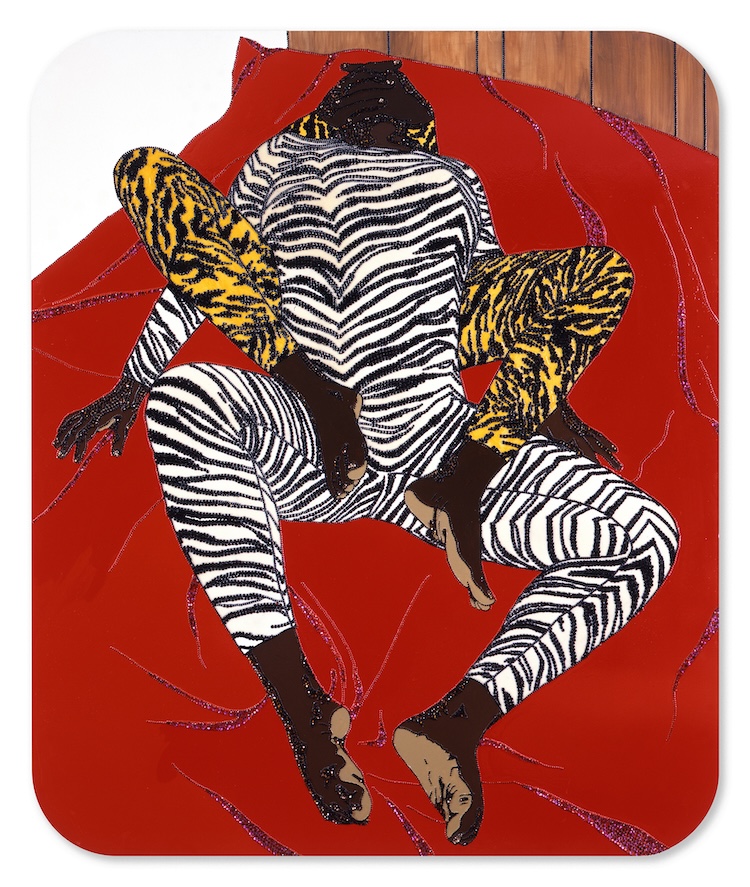

It begins, as I think a Mickalene Thomas show should, with her relationship with her mother in Camden, New Jersey, with interiors from both the home in the 1970s as well as a tableau showing Sandra’s home a bit later in the 80s, two different periods of her mother’s life. We are partially recreating an installation in Los Angeles, an early body of work called The Wrestlers. So the show opens with those immersive environments.

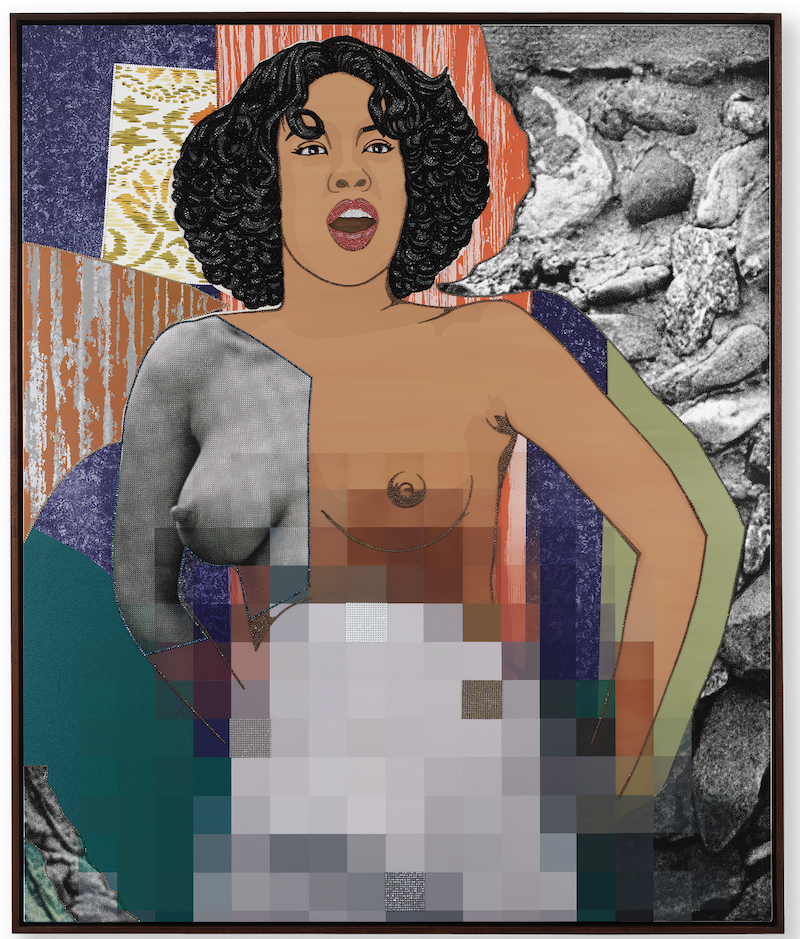

Mickalene is such a dynamic creator of environments, whether it's the interiors of her mother’s life and celebrations and parties when she was growing up or really overt moments that reference Black culture, say, through the auspices of Jet Magazine. Those are far beyond discreet collages and paintings. They are environments, and she approaches every show that way. So we’ve tried to build the broad installation as a collection of the genius in regards to installation and built environments. We want people to feel comfortable and at ease, to feel invited. Everything that we’re doing involves taking those moments of Black joy as expressed through a publication like Jet and expressed through her muses, whether that’s her other, Eartha Kitt, Diahann Carroll, or the movie The Color Purple. Those touchstones will be present in the installation to evoke the senses of love, community, joy, and struggle—that’s what we’re trying to do.

(portrait of Mickalene by Emil Horowitz, 2024)

I immediately experience joy and welcome (and more joy) when I look at the work. There’s more to learn and experience in her art, but I don’t feel a barrier.

I think that is one of the powerful lenses that Mickalene brings to the table. So often we’re at this vantage point where we feel at a disadvantage towards culture. Wherever that’s coming from, whether art history or museums as imposing places, or expectations of culture of how we get involved, we can often feel that culture is looking at us rather than the other way around. Mickalene’s strength and dynamism are that she allows herself to look at someone like Picasso, Courbet, or Monet, fully secure in her identity as a queer black woman coming from Camden, New Jersey, and that is an empowered position that is not taken for granted.

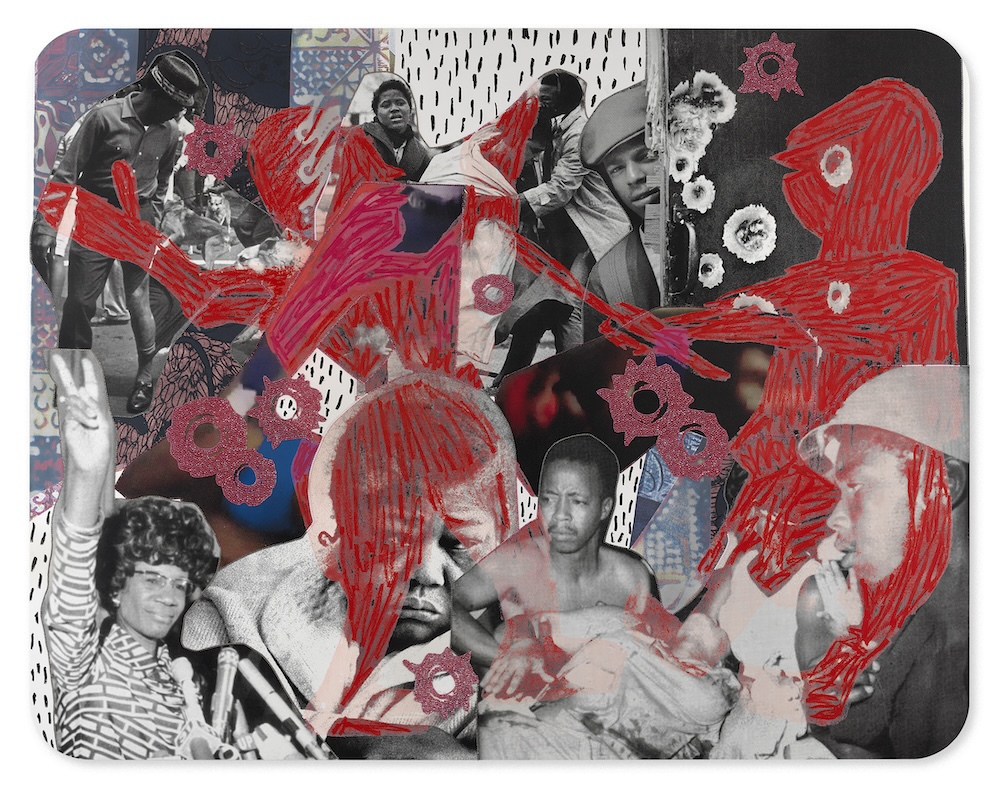

She doesn’t assume, like culture often does, that we should approach a figure like Picasso and value that just because he’s Picasso. We engage with him and determine our own value according to where we are standing. It’s not a requirement, and so those women she loves, she puts into the poses of Courbet or Delacroix. It’s a critical position, and that critical position is a struggle. Later in Mickalene’s work, with the emergence of a body of work called the Resist series, the struggle is more overt. There she uses that political position that Picasso took as a way of looking at the murder of Black individuals at the hands of the police, the history of incarceration, and the suppression of uprising and revolution.

From my point of view, you can’t think about Mickalene Thomas fully without the Resist work, without these moments where she turns a resistant critical lens at someone like Picasso or even Jet magazine, this conduit of Black culture, an extraordinary register of the Civil Rights movement. But it also had a pin-up calendar and took a position that can be examined on aesthetics, on what beauty is and who is chosen as beautiful, which, from a certain point of view, was something oriented towards the male gaze. Men are looking with desire at women. What does that mean when Mickalene, as a queer black woman, turns her desire, embracing her desire for the Jet beauties of the week, and approaches those women from her point of view, thinking about sexuality through that lens? It’s a very dynamic practice.

She’s inviting us to do the same—to view moments in our own lives, from our own positions, through her paintings?

Absolutely. I think she wants to empower each of us to embrace our experiences, embrace who we are personally, and get into the joy and business of who we are, where that comes from, and be comfortable with that. And that’s where bell hooks comes in because she is saying the same thing.

What a wonderful way to approach art and life. I mean, why be intimidated by a piece of music or work of art?

It’s kind of the double-edged sword of art because the fact that it can be uncomfortable or frightening is where it gets a certain amount of its power. But the mechanism by which we engage that difficulty is a mechanism of personal empowerment. It’s paradoxical that we can useculture to improve ourselves through difficulty, and it’s not merely an affirmation; it’s a work of struggle.

I’d prefer the experience of being invited by the artist to struggle and then discover the joy. So, more about Mickalene herself. Do you have an idea of what she had in mind when she first started making art?

In interviews, she has spoken of making art as a child, especially the collages. She came out as Gay at around age 16 and, after a few years, ended up in Portland, where encounters with artists offered her encouragement. But the big influence was seeing Carrie Mae Weems’ Kitchen series at the Portland Museum of Art, where she sees a Black woman in an environment that she recognizes, playing roles and critiquing those roles at the same time, looking at marriage through multiple lenses and sort of investigating husbands and lovers and all the things that go on inside a domestic situation. The radicality and locality of that appealed to Mickalene, and within a few years she moved on to Pratt and then to Yale, where she initially practiced abstract painting. But through photography and performance classes, she started to photograph her mother and take on the subject matter that would become what we know her for.

I was surprised to see abstract elements in her work. Can you tell me more about how she used abstraction?

We don’t have any of those early abstractions in the exhibition. But if I had to speak generally, I’d say that it takes time to find your voice, and a lot of people start with abstract painting. There is a march towards it, and one of the things that will be visible in the show is that early in her career, we see her muses directly. The collage elements move through her composition but are a function of the environment. So as you look at early portraits, you’ll see the fracture of interior design, of patterns and textiles, and the design features in the environment. As her career goes forward, that collaging and abstraction moves on and into the figure. There’s a point where, for instance, she starts to paste an eye on top of a muse’s face. There’s a great portrait of her muse, Din, to which she applies a hand drawn eye. Then that progresses, and the muses become engaged through the medium of collage, leading up to a body of work that visitors will see called Tete de Femmes. As I look for the figure, I look for the personality and identity of the subject in its displacement and fracture. So that early DNA of abstraction continues to manifest and will be on full display in the last gallery of the exhibition. Some of the most updated works in the show are perhaps more abstractions than portraits.

How is the show organized? Will it be chronological?

I often think of artists who return to subject matter and reinvestigate it over the course of their career, to present a chronology. A visitor will absolutely feel the chronology of Mickalene’s career, but there will be moments where later work is put in dialogue with earlier pieces to show how wave falls upon wave and how return to a subject is part of her ethic from the beginning.

She has some really big paintings, so how will they be hung within the show?

Most often, they’re under the auspices of an installation. We’re using wallpaper, carpeting, wall treatments, mirrors, plants and paint, so yeah, there is an emphasis on creating environments. It will be tableau focused, so there will be a room dedicated to the Wrestlers, featuring paneling, carpet, and bean-bags. There will be a large space with a video called Angelitos Negros, which is going to feel like a living room, complete with furniture where people can sit, hang out, and read.

As someone who has lived with her work and done so much research, what is your favorite personal impression of Mickalene Thomas and her show?

What I’m excited about is what we talked about earlier, the empowerment of local experience, because I often feel intimidated by culture, even having been engaged in it for 20 years. Even though this is my 12th exhibition at the Broad, I’m not exactly a rookie, but I continue to feel daunted by contemporary culture. Mickalene is saying: Yes, culture can be intimidating, but we should be empowered to bring our local point of view and feel fine about that. And if we’re a queer Black woman, that is the lens and that’s okay. We all have our own identities and those moments where we have to make up our own minds and not be dictated or talked down to by culture. It’s a matter of us taking responsibility for our own lives. And that is fantastic.

Mickalene Thomas: All About Love is on view at The Broad in Los Angeles through September 29, 2024. This article was originally published in Juxtapoz Summer 2024 Quarterly.