Just six months after graduating from Yale, Vaughn Spann is making tracks in the art world with major shows and accomplishments lining up, logging in one after the other. The number of notable group shows includes exhibitions at Almine Rech Gallery in London, the August Wilson Center in Pittsburgh and Night Gallery in L.A., as well as his sold-out solo show with Half Gallery in NYC. The Florida-born artist was recently in Miami to see his work, curated by artist Nathaniel Mary Quinn, included with Half Gallery’s exhibit at NADA, David Castillo’s booth at Art Basel, as well a Rubell Family Collection exhibition of newly acquired work. To put this into context, this is just the beginning.

Fascinated by his diverse body of work that includes both classic portraiture and texture-rich, mixed-media abstractions, we anticipated this conversation where we could learn about his background, his perception of the art world, and what drives his unique practice.

Sasha Bogojev: Showing both abstract and figurative work at the same time isn't the most usual way to go, right?

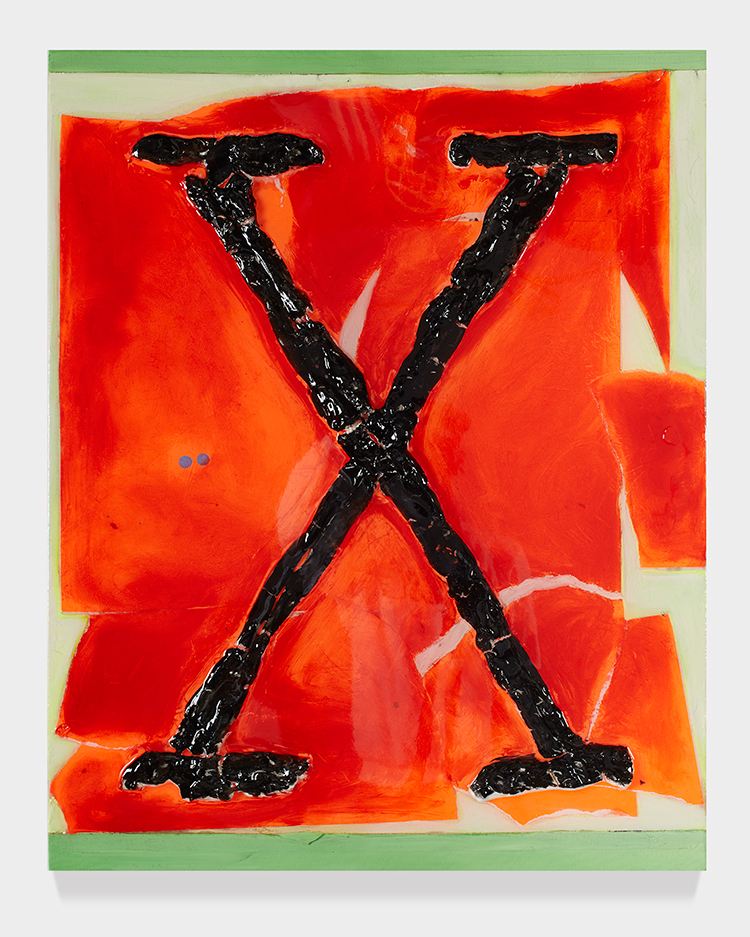

Vaughn Spann: My practice is a bit conceptual, and it oscillates between figuration and abstraction, because I'm interested in these stylistic separations and distinct breaks. As artists, we're human. We have complicated ideas about everything. And I feel it would be a disservice to limit those ideas to one framework. I feel it's such an unfortunate position for artists to be in, being determined by external factors. So I'm really challenging a way of making work that tries to embody all the things that I am, the people I encounter, the places I've gone, the things I've touched. All the things that actualize who I am as a maker, an artist, and a person.

I remember browsing through your work and thinking, "Is this a group show?"

Ha ha, I get that a lot, and it's a very fair statement. But the rich thing that is happening right now is that, as more people begin to see my work, they can look at it from an angle where they see threads that connect them. So I'm finding these axes to move them through space and discover different angles to my work.

I must say, it’s a pretty ballsy way of producing work.

Well, thank you, I appreciate that. It was something I had to grapple with and do the work for. It's not gonna easily give it to you. I find it a very energized place to be in as a maker. A place that is really liberating, it gives me access to think about my agency as an artist, about conceptual ideas, different avenues of making which I find so, so important.

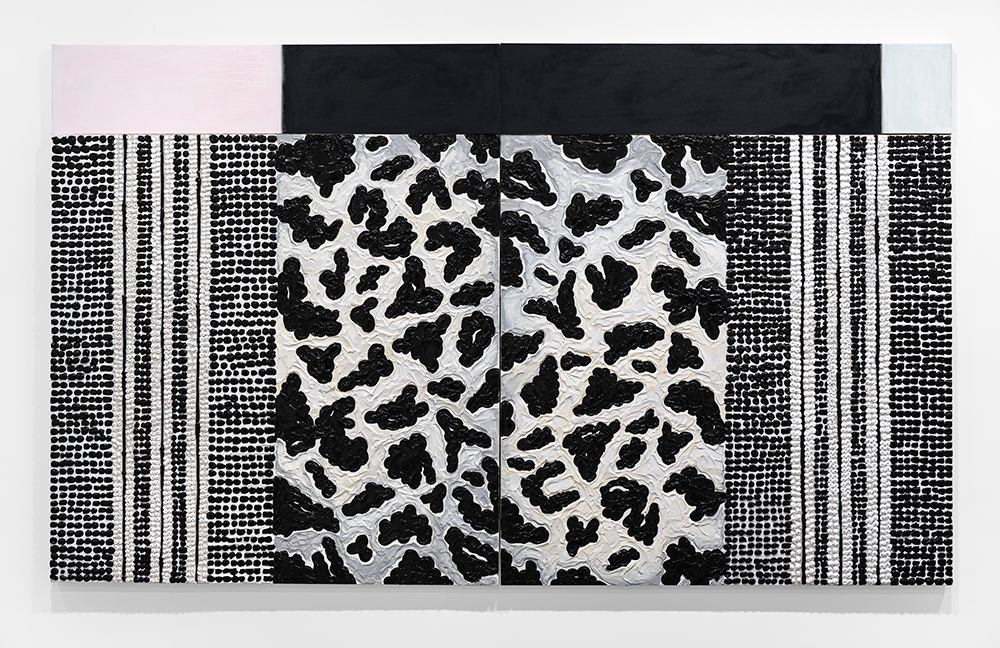

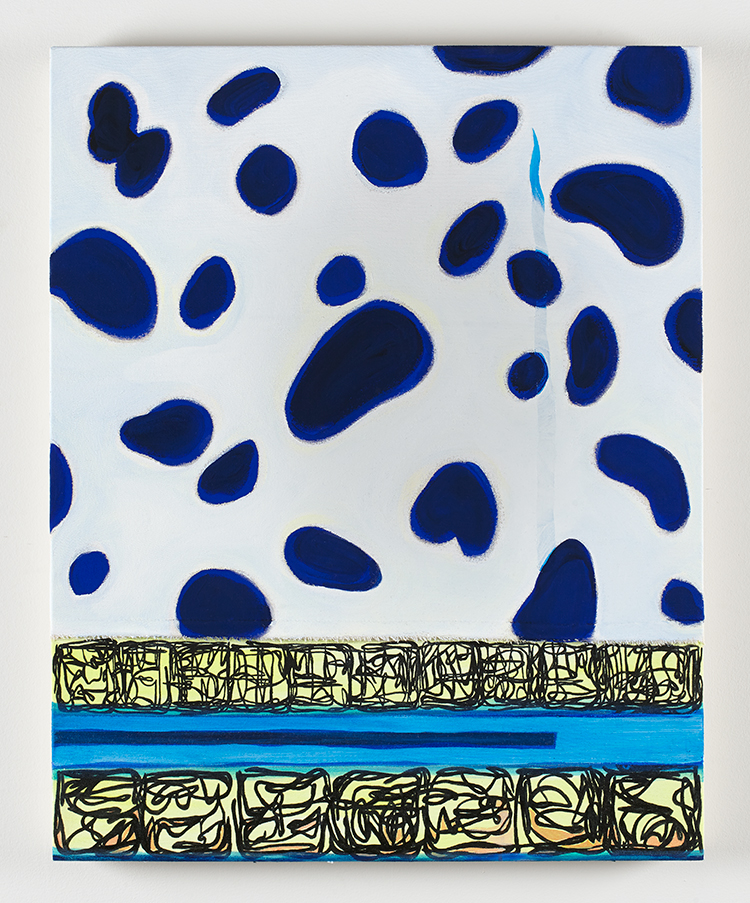

Let’s talk about the Dalmatian series. What is that one about?

We keep hearing about art being about current times or times we live in, artists needing to work from a subjective position, and things like that. So I'm really interested in speaking about the work through the lens in which I exist as a person, and as a black man, in particular, also, the ways I experience the world as a westerner and US citizen. Growing up in an urban city, concrete jungle, per se, when I think about the neighborhood, one thing I noticed is that people had animals. They would have dogs that would protect or guard their homes and domestic spaces. They were usually rugged animals, like German shepherds and such. So these are experiences I have from my youth. As an artist, I got caught up thinking about these ideas of class, social aspects, ethnicity, and all these higher notions; so every time I'd see Dalmatians, they would be associated with things around wealth, desire, those markers of money and class. They were also part of the entertainment industry, so a firefighter in a TV show would have a Dalmatian, so I kept wondering, "Where does this exist?! This is not the America I know!" It was something very micro that meant so much to me. So I was always interested in the ways I was fed these false social realities that don't really exist for me as a person.

How does something like that reflect on your actual work practice?

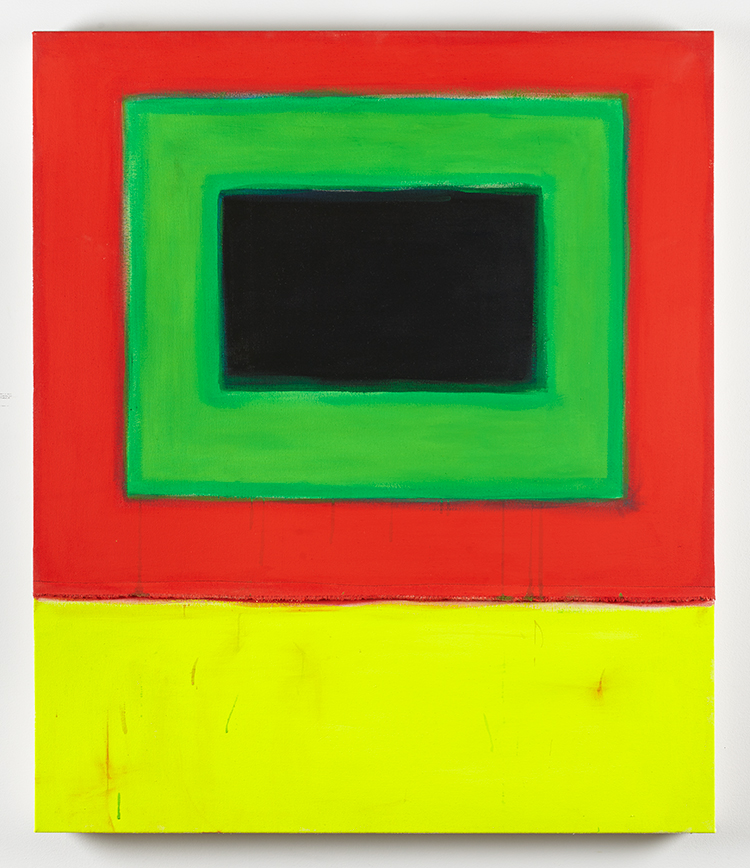

So, as a painter, the way I approach my art is that I think about the lens of the society, because I can't remove myself from that. My day-to-day things, things I stand for, sort of tack against the way I think about art. So I like to think about those positions as I make my work. I'm not a formalist painter, but I really engage in histories of formalism, the way we think about color, about composition, about geometry. So I'm thinking about formalism, thinking about the social and political, thinking about the ways in which all those things are tied up, whether subtle, subvert or overt. I'm interested in thinking about the painting for painting's sake, but I cannot ignore these other issues and concerns that really affect who I am as a person. For me, it’s about tying them together and considering how to think about painting, tangility, time, motion, and all these different things that inform my practice.

Give me an example of you tying up those things.

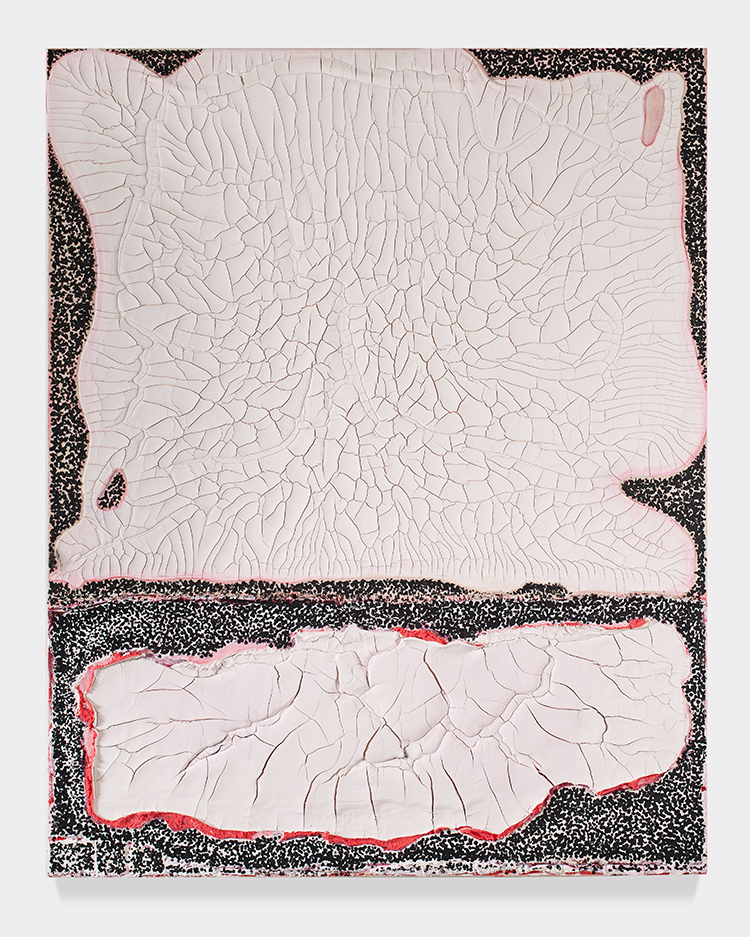

So, I grew up in my grandparent’s home. My parents were around, but they were out working a lot. They had very, what you would call, stereotypical social norms. One of the materials that come in my paintings is terry cloth. On Sundays, in my grandparent’s home, my grandmother and I would fold towels. It was a way of learning responsibility, but also to bond with family. When it comes to painting, everything needs to be tactile, so I have a very physical approach, amd when I do make figurative work, I have the desire to speak within these beautiful traditions that I saw and still admire.

Did you first start working figuratively and then move to abstraction, or was it the other way around?

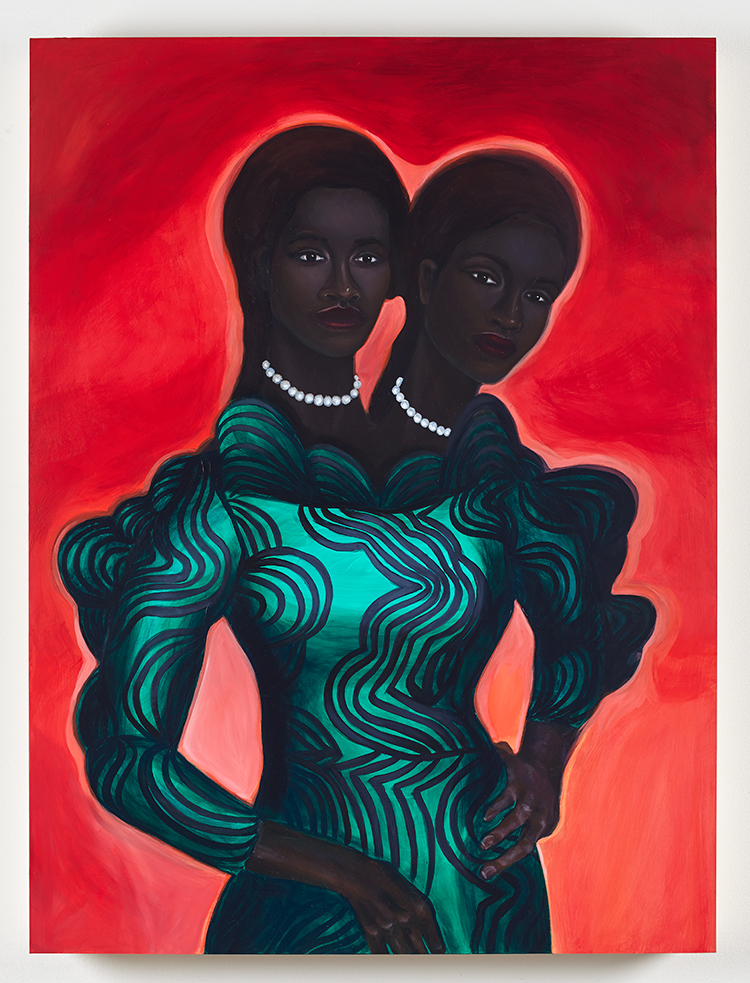

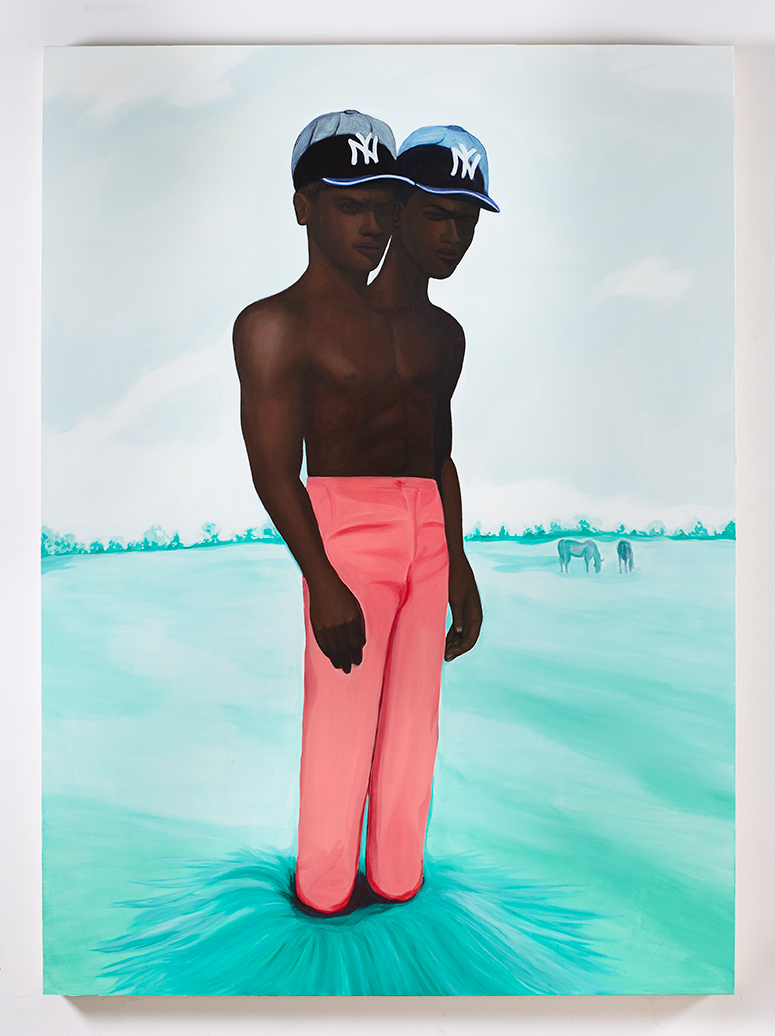

I always considered myself a draftsman. Growing up, I was the kid who always drew, mimicked people, made portraits, drew cartoons, that was my forte. But as I grew up, I had other interests, like I was really good at science. When I started undergrad, I was a biology major, but that wasn't my real passion. So I switched my major to art, cause that is what genuinely gets me excited. And while I was studying and living with my wife, I was working with materials that were given to me or had a personal history as a way of being resourceful. But, when I moved to Yale, I felt entrenched in the things that I knew, and I thought the healthiest thing to do would be to move from the things I know, and question the things I don't know. So, the first year at Yale, I moved away from abstraction and started working on what I call the Symbiotic paintings.

They are really dealing with our existence within the environment, within the world at large. The first substantial figurative painting I made from that series was a two-headed painting called, "I grew an extra head to watch over my brother." I felt that idea on the poetics or the metaphor was so powerful, especially when, for example, black men are being killed on the streets by police. Or on the other side, we have violence within our own community. Every which way you think about the black body, it's the body that's disposable, dispensable. It can be taken away or removed. So I thought about the poetics between the idea of having a second head to be vigilant. To watch over yourself, take self-care.

How do you feel about accidents in your process?

Accidents are actually really important. For example, my abstraction works are all sewn, and I like to work on a big scale, ’cause I'm a tall guy and I like to work in that way. So when you scale up painting and try to sew it on a sewing machine, it's a mess! You just have to be aware that you will make mistakes and these accidents could be prone to the work, and you have to embrace them as the part of the work in a very beautiful way. So I'm interested in allowing the work to become itself. While I have ideas of where to move with my work, I also want to be open and take whatever comes, and accidents can be one of the most fruitful places.

This article was originally published in the Juxtapoz Spring 2019

vaughnspann.com

(Portrait of the artist by Anthony Alvarez)