Though the experience of being a teenage girl is not an experience that is universally relatable, there are some truths about the summer before high school that likely resonate far and wide: you are the most awkward person who has ever lived, home is a suffocatingly small hellscape, and music is life.

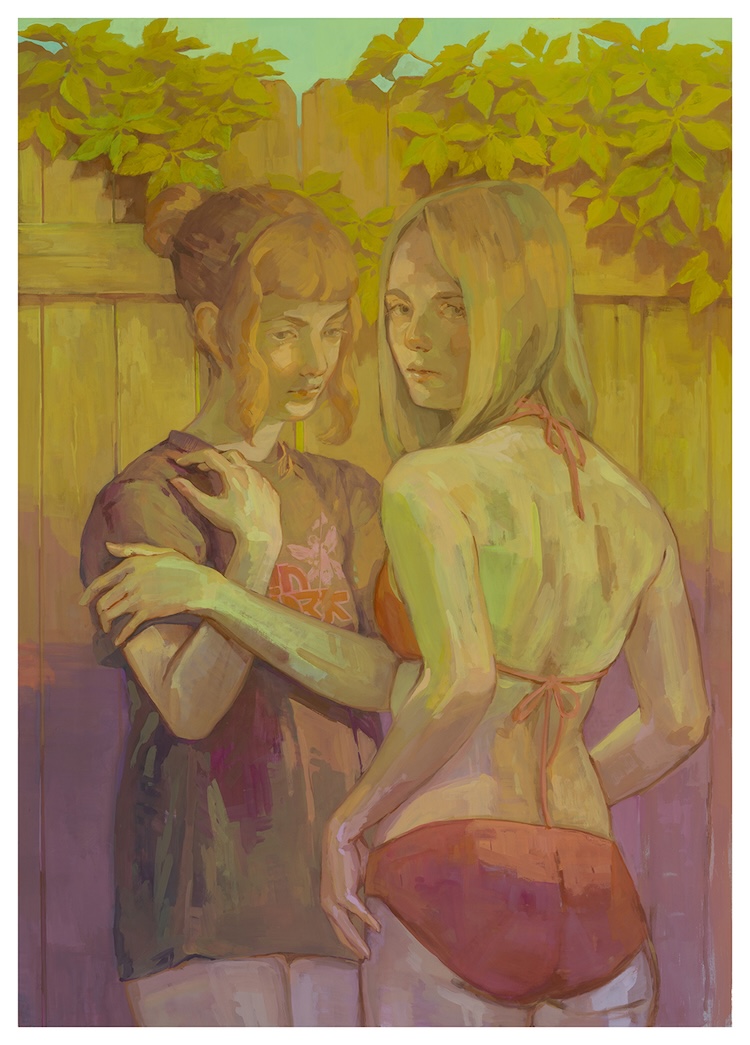

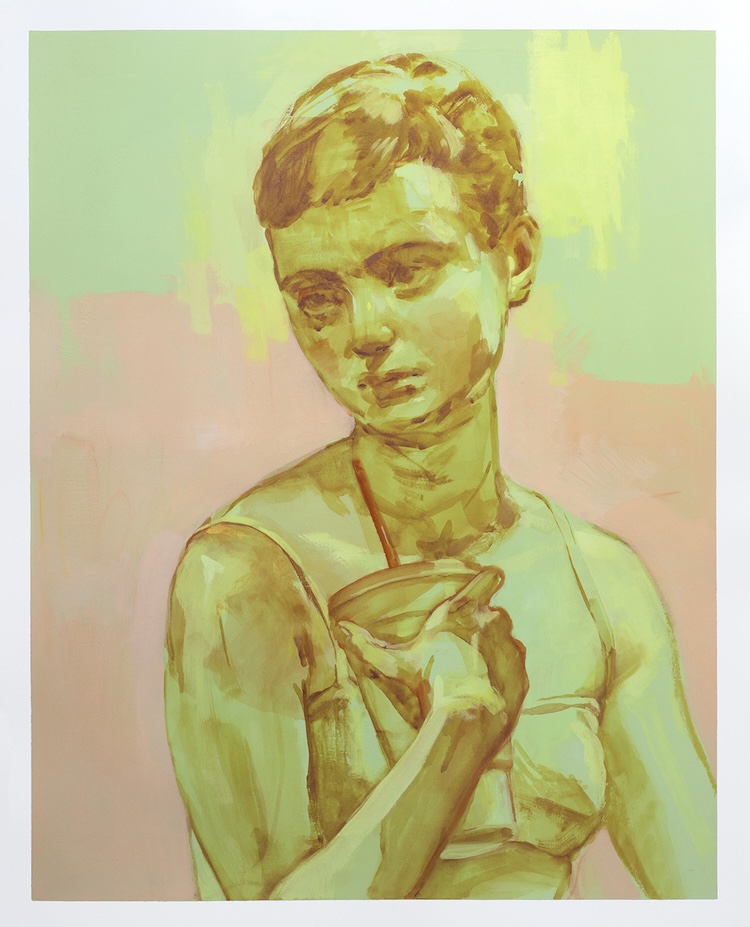

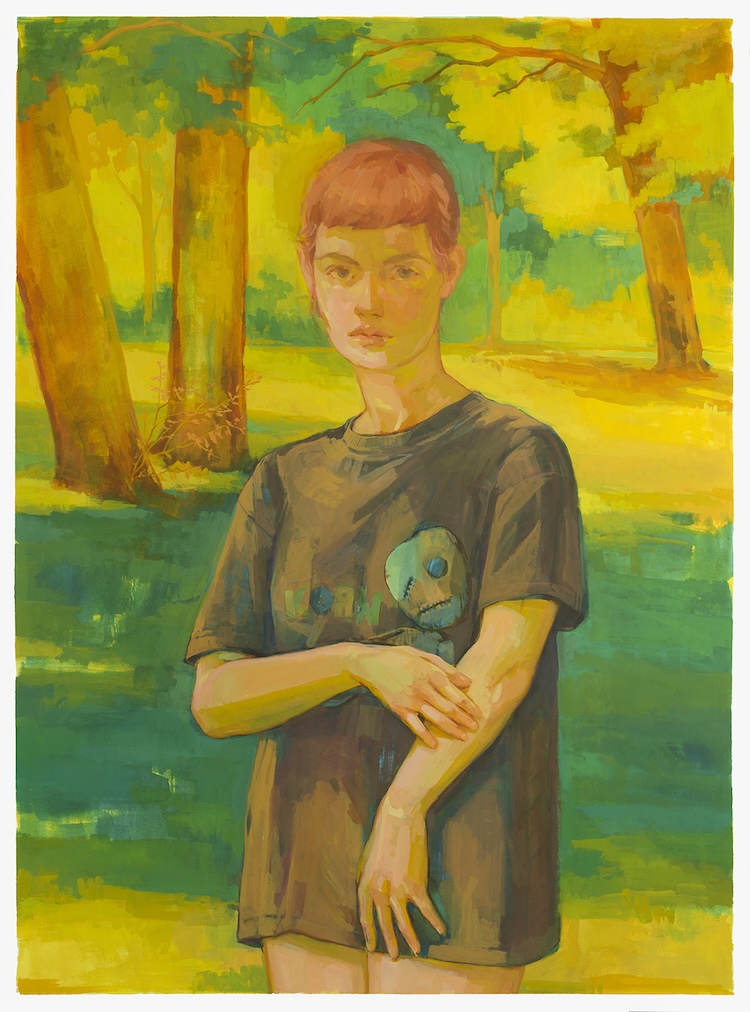

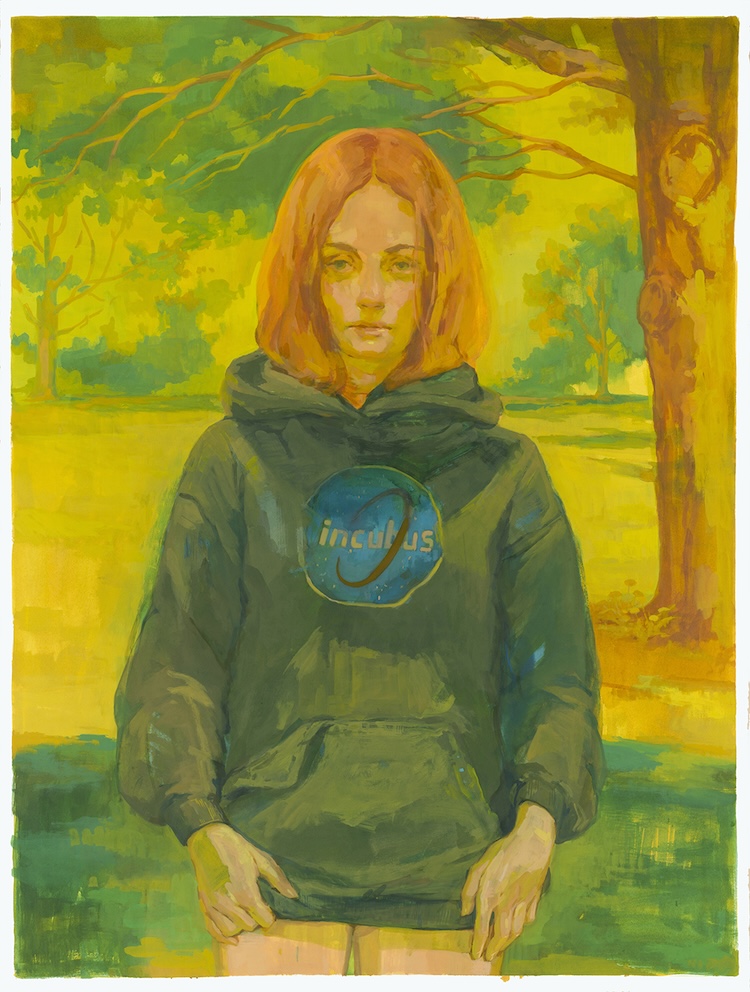

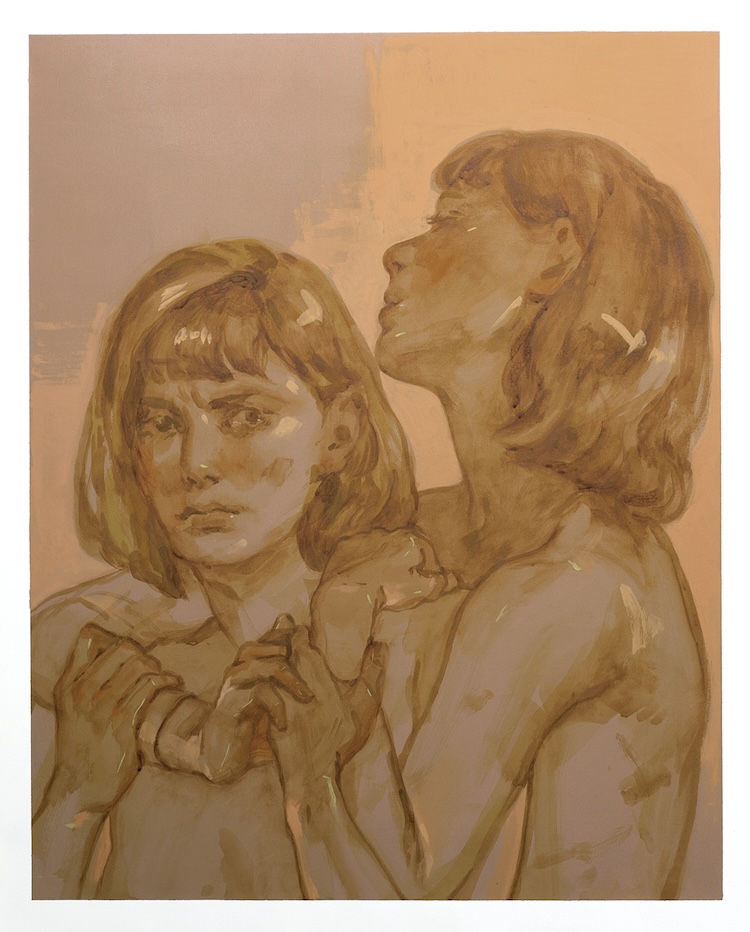

The paintings in Rachel Gregor’s solo exhibition at Hashimoto Contemporary, Still Summer, explore these themes of shame, entrapment, independence, and aggression from the perspective of a group of nefarious and awkward teenage girls. Before the opening of her show, Gregor caught up with Hashimoto Contemporary’s Katherine Hamilton to discuss her influences as a painter, building complex psychological narratives on the canvas, and why teenage girls are always underestimated.

Katherine Hamilton: Since much of your work draws from life, verging on auto-biographical, I wanted to start with some questions about you: are there any specific memories you have about your first engagement with art? Were there any artworks or media specifically that prompted you to start painting?

Rachel Gregor: My mom was an illustrator and graphic designer so she was always really encouraging when it came to my interest in drawing at an early age, so much so that I don’t remember a time when I didn’t self identify as an “artist.” I always thought of myself as one and never questioned that I wouldn’t be one, even if I didn’t really understand what that meant beyond just drawing a lot. When I was in middle school, I had joined DeviantArt and entering into those online communities made it feel more serious. Understanding what it meant to be an artist really started to click when I got this big encyclopedic book called The A-Z of art—suddenly, I was looking at everyone from Mucha to Judy Chicago. I remember feeling really attached to Dorothea Tanning and I tried to replicate her work through my angsty anime drawings. Somewhere along the way, I got a bunch of craft paint from a church rummage sale and started painting on pieces of cardboard.

Your family and their flower nursery became an influence in your painting practice. Was this a subconscious influence you realized later, or something you knew right away you wanted to incorporate into your work?

It was an influence that I realized later. Growing up so deeply embedded around something, I feel like you can’t help but to take it for granted. Going out to the greenhouse and having to water plants or dead-head geraniums was a chore, something that as a kid you resent a bit. Growing up around all that foliage, and rich bright colors, had to have stained my brain in some way though. I remember in highschool I started making some edgy drawings about being choked or drowned in plants, and I feel like I still want to maintain that overwhelming feeling with botanicals in my work: it’s not just pretty romantic posies, there’s thorns and weeds and decay.

Speaking of influences, I remember you saying that at a point in your painting journey, you began looking at Manet for his painting style’s thick, rich qualities. You also mentioned that Giambattista Tiepolo was an inspiration in terms of the psychological drama he shows through the gaze. Can you expand on your painterly influences for this show?

I’m always, always looking towards Manet for understanding of mark-making and how he depicts form and volume, and trying to interpret that system of mark-making with oil but then translating it to gouache which is so, so flat and matte, but you still see the history of every brush stroke. Every mark in a Manet shows you something about the light or the form of what he’s depicting, and I felt like that awareness was important for me to have with gouache—there isn’t much room to hide. I was surprised, though, at how much I ended up looking at George Caleb Bingham. He has that same sense of theatricality that Tiepolo has, very frontal and presented compositions. He has a fantastic sense of color and atmosphere, everything feels so romantic and optimistic yet humid and stifling. There's a dead tree in a painting of his called Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers through the Cumberland Gap that pretty much directed the entire palette for my piece Still Summer.

What strange or peculiar influences might we not recognize from looking at your work?

Probably my love of fiction and fantasy, or silly humor. I’m usually listening to a goofy Actual Play D&D podcast while I work or Lord Of The Rings. I think this comes through in my work a little more, but I also read a lot of the Bronte sisters' works routinely, as well as their contemporaries like Gaskell or a little later like Edith Wharton.

You’ve also mentioned that you continue to use your own face as a reference for the figures in the works, often changing their features to resemble how you used to look, how you have dreamed of looking, or into a stranger altogether. How do you frame these multiple selves within the freeze-frame narrative moments in the paintings? Do you see yourself in other people, or vice versa?

When I’m starting a composition, sometimes it takes a while to find the narrative, or the emotional beat of what could be going on. It can be a slow discovery process of who is being depicted, and once I start to find an emotional standpoint for the figure, I understand more about who they are. From there I can start to ask questions like, “If they are the kind of person who feels like this, then they might have this body language, or they dye their hair, tie it back, use it to cover their face...” My biggest point of reference for those moments is myself, when I have felt that way, when I have shrunken back or had a moment of weakness, when I felt I needed to be bullish, or when I’ve experienced feeling uncomfortable and how that other person in that situation felt to me. I try not to project myself too much onto other people and their experiences, that’s why my figures can be a bit homogeneous. I don’t want to feel like I’m speaking for someone else and putting words in their mouth or trying to tell a story from a point of view that I don’t understand.

You mentioned that part of the impetus for making the series of works in Still Summer came from finding an old roll of film from your final days of middle school before summer break, using the hue of the film and positioning of the figures as direct inspiration for the works. But I believe you don’t often work from photos—so why now?

The choice to use photos that I had found from middle school was kind of a magical happenstance. I had already been working on this body of work for a bit, and while visiting my parents house I was digging through an old desk drawer and found that pack of photos. I was trying to recall distant emotions and it felt very vague and abstract, then suddenly, there they were! Frozen in time and perfectly preserved. It felt like finding the missing artifact that proved a hypothesis.

I used the images as an emotional starting point: sometimes I would borrow poses or I really wanted the specificity of the background in a lot of the photos. Many of them were taken at a park and I wanted to include those details. But I would not say that these are “photo referenced paintings.” So much has been altered completely and recontextualized. If this were a movie it would have the disclaimer about this being a work of fiction and any relation to any real person is coincidence.

What’s your best summer memory? Your worst?

The summer between 9th grade and 10th grade, I started riding my bike everywhere. I feel like that was my magical highschool movie summer, where it felt never ending and easy. I remember the summer before 9th grade, though, was awful. I think that’s when I knew that my friend group from middle school was gone and high school was approaching, and it was going to be rough. That summer felt like purgatory.

I want to discuss the psychology and narratives you create in these works. I associate tragedy and ecstasy with the period of life you portray: learning about desirability, perhaps for the first time, beginning to internalize societal expectations of young women, and yet attempting to define oneself against our parents’ expectations, choosing who we want to become. We can read through the figures’ gazes and body language that they’re in these torn, tense states. What’s your approach to showing the painting’s inner narrative through a medium without words?

I think like you said, it comes all down to body language. As a painter, my hope is that I can depict a figure that can convince a viewer that it’s human-like enough to empathize with the image. We can then sense what kind of emotional state someone is in through interpreting body language or reading micro expressions on a face. We can tell someone is sad without being told so just because that language comes across in the slightest ways we might tense our facialmuscles. When I’m working in my studio and trying to construct a figure, and it just doesn’t feel right, I’ll tell myself that the “acting” isn’t there, and the whole process does feel theatrical.

When it comes to multi figure compositions, then I start directing the limbs of the figures more or the gaze so they act as visual key points for how the actions in the image is read, so the viewer knows what scenario is taking place. It’s not just what is being acted out in the scene, but how it’s constructed that allows a certain movement throughout the image. Hopefully, if one figure feels trapped, you as the viewer also get that sense of confinement.

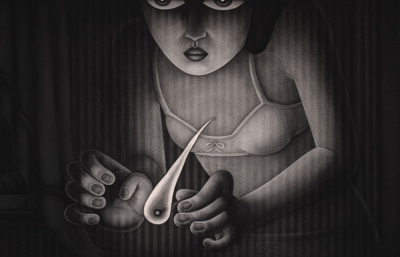

Entrapment and isolation are some heavy themes in this body of work. The girls are often pushed up against a fence, isolated on a dock, or the landscape they could flee to is obstructed. You also included a series of still-life paintings in the exhibition that emphasize the sense of confinement—cinder blocks near the wooden fence and overgrown weeds in the cracks of the wood posts. What about girlhood or female adolescence feels so confined to you?

Adolescence can be so confining because it’s the first time you feel like you have some independence but there’s so little avenue for agency, at least that’s how it felt for me. I grew up in a more rural area, and I felt very isolated from the rest of my friend group. Because of that physical distance, I felt more left out than everyone else in general. These figures exist in a kind of physiological liminal space, but at the same time I do want the physical space around them, the compositional space, to feel purgatorial. I do want that sense of dread that there’s no escape, because that’s how it felt: that there’s really nothing worthwhile beyond that field or that tree, just more fields and trees.

One of the ways the figures seem to escape is through music, specifically Nu Metal like Korn or Incubus. In society, there’s this persistent phenomenon where it’s thought teenage girls can’t “really” be fans of such an aggressive form of expression, like a disbelief that something soft can also be vicious. Why do you think these girls are underestimated?

I think, unfortunately, to be dismissive of “the little girl” is something so deeply ingrained in our society. She is small, weak, misguided, naive, needs protection, needs to be corrected. We assume She needs our help and we assume She can’t possibly know any better. It’s a frustrating thing to experience—I’ve always had a small frame and even as a full grown adult I find myself being dismissed by strangers for being a “little girl.” It’s a perpetual state of being infantilized, and we don’t like it when something that’s supposed to be non-threatening starts to display aggression. So, the easiest thing to do is dismiss it as being pathetic or “just for attention.” If you dismiss the threat, it gives you a false sense of safety.

What's a piece of advice you would give to the girls in the paintings?

If I know anything about the girls in my paintings, it’s that they would not take my advice. They would probably actively act against anything that anyone acting with authority would have to say, regardless of how well-meaning they might be.

Still Summer is on view at Hashimoto Contemporary Los Angeles through December 2nd. Opening reception and installation photos taken by Megan Cerminaro.