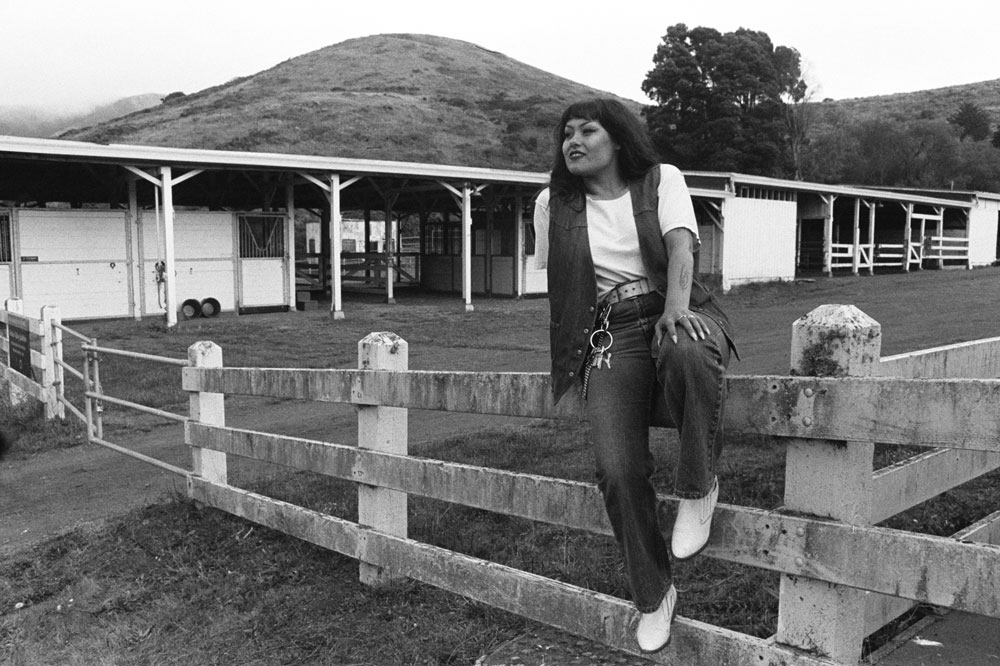

The pin-striping and sign-painting work of Lauren D’Amato has distinguished countless corners and cars of San Francisco. We met five years ago at the Juxtapoz Clubhouse in Denver, when, overnight, several artists flipped a warehouse into an art extravaganza. Corrugated metal her backdrop, D’Amato was outside diligently working her wonders on the custom signage. Since then, innumerable artists have cited D’Amato as an influence, and her practice has pivoted. As rowboats, buildings, and Chevy Impalas proudly grandstand all over San Francisco, emblazoned by her hand, she’s retreated to the hills above the Golden Gate Bridge to refine her mission.

Kristin Farr: Beyond your middle name, do roses have a personal significance for you?

Lauren D’Amato: Completely. I am actually the namesake of two different women on each side of my family named Rose. I believe there are real eternal ties to the image of the Rose. It has been carried as a visual symbol for physical adornment and showmanship, from traditions of Charros, embroidery, and pottery, to contemporary lowriding, pinstriping, and tattooing. Being a pinstriper is such an intimate way to participate in these traditions, and I find the role I play is really helping others make these unique visual statements of individualism and resilience. To call something a Rose is to say that it stands out above the rest, and for me to paint them for others on their prized possessions in these traditional techniques is also a physical way for me to share pride and participate in my own lineages.

Describe your background as a sign painter and how it’s in your genes.

My Uncle Howie started a sign shop in New Jersey in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and he got my pops and my other Uncle Joe to move out there from LA and work for him. He trained them both, and they had a really dreamy family barn shop setup. They did a lot of carved wood and gold leaf signs in a more rural area. By the time I was a tween, my Uncle Howie had relocated and started a shop in Arizona with his son. My parents used to send me out there on little solo trips and I spent some really informative time in their shop. My Uncle taught me about drawing letters and I got my basic knowledge of their day-to-day routine—painting signs in the old western towns, big saloon signs, and huge cut-out cowboys.

I remember one trip, specifically, when my Uncle Howie had been working on signs for a local rodeo, and after the job was done, we went down at night to watch the riding. I remember acknowledging then that he got treated with so much respect (good seats, free beer, and food), all because of the work he’d done. This was very inspiring to me.

How did your sign-painting practice evolve over time?

From that initial family introduction, it has held this place in my heart that’s very dear to me. My family encouraged me to pursue design or something else that would be more profitable; they wanted more than for me to be tied down to the more blue-collar aspects of sign painting. So, after going through art school at SFAI and being exposed to an entirely different world of art, I had to piece back together my artistic identity. I decided to shift towards embracing this lineage more openly, against their advice and took an apprenticeship at New Bohemia Signs in San Francisco. I worked and learned so much there for several years and was in very good company with so many incredible painters. It was during my time there that I began to try to develop my own style and try to distinguish a look for myself as a pinstriper. I’ve had a good stint of running my own small sign business in San Francisco, pinstriping and also teaching hand-lettering at CCA for the past four years. I’m now at a stage of re-envisioning what all of this has meant to me.

Tell me about your Kustom Sunday parties.

It was something I started pretty casually out of my warehouse garage in Bernal Heights as a way to build up my chops and get myself to paint more confidently around other people. I realized while I was working at New Bohemia that I would experience some performance anxiety on jobs. I found myself in these crucial moments where clients were entrusting me to make their most precious belongings look even better, so that felt like pretty high stakes! I opened the garage roll-up on these Sunday afternoons, offered vehicle lettering and some simple striping, and invited my friends to DJ oldies. I had a good friend, Rene, who started the Suavecito Souldies nights in Oakland, and he was the first person I invited to join me. I used to go out to his DJ nights religiously in Oakland and dance on Friday nights at the Golden Bull. It was so memorable, and hearing that music also gave me a sense of comfort that allowed me to paint better.

Kustom Sunday grew into a fun event. There’d be lines of people who’d show up in their old schools. We would barbecue and people would watch me paint. From the garage, I ended up moving around the city and having them with the lowrider council at La Raza Park, Golden Gate Park, and even one in LA. I invited other painters and DJs and I’ve made some of my closest friends and clients through the introductions made on these Sundays.

Congratulations on your residency at The Headlands. How is it going, and what made you want to work there?

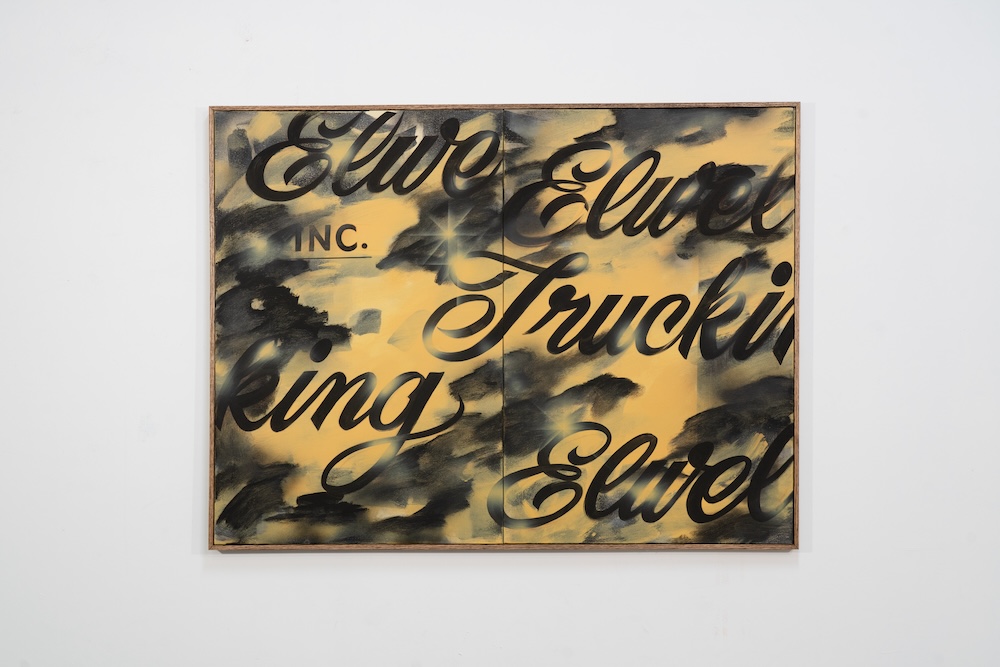

I’m at the beginning of my Tournesol Award period at the Headlands and focused on making a new body of work in painting that references all lettering from signs in San Francisco, using my sensibilities as a pinstriper to address color and composition.

A lot of the signs that were initial inspirations for me are here, but also hanging out on a limb in such a fragile state, so referencing their forms in my work is, in a way, a means to document and hold onto their memory. In these paintings, I am utilizing all the different techniques I’ve learned over the years, like lettering, airbrush, and pinstriping, as well as allowing myself to move freely through these paintings to really reflect and honor the road that’s brought me to this point.

Through this journey of wanting to become a better sign painter, I have developed an intense internal need to know that, at the end of the day, I can sustain and support myself solely with the brush. I’m going through a transformative period and learning to mitigate that by reprioritizing my own creativity.

Let’s talk about your recent Complete Machine exhibit at the House of Seiko Gallery.

The Complete Machine show was a major point for me. I realized something about the ways I work and how shifting between painting processes and using abstraction could actually create an image that felt whole to me. After the show, I noticed a thread in the group of paintings that I had overlooked. The signs I had come to reference in the work had all, in that respective moment, been non-functioning signs. It’s something I suppose I am regularly drawn to, signs that have transcended their original use but maintain their visual presence in an environment. Removed from their intended function, they ask us to consider something else, maybe something that relates to the memories they’ve held, or to look into their surfaces and see the language of blue-collar labor and technical ability that persists and presents itself there.

Tell me about the sculpture at that show.

That work was a whole experience—intentionally so, too! I was feeling really inspired by being in this huge industrial space where my partner Stephen does a lot of metalwork and fabrication, and kind of thought about that sculpture as being a place to bring together all the physical materials that I would interact with in my day-to-day work, creating this glowing, sparkly, spinning, time-keeping object to paint in action. We documented it in 8mm and included footage of us both working in the shop. Stephen helped weld and put these spinning hubcaps into a lightbox sign and I painted it, surrounded by all the motorcycles and machinery. Something about documenting it in the 8mm film is so special to me, because a lot of my first memories of even seeing anything like this represented in museums or institutions were from seeing old Kenneth Anger films, and they were completely exhilarating.

Do you have feelings about the imagined line between design and art?

I went through a long period of feeling like my perceived identity was compromised by the way these worlds are historically separated or the inherent hierarchies at play between them. Comically, they each carry such harsh stigmas against each other. I’ve come to this extremely liberating point in my life, though, where I’ve realized these lines actually are the subject matter at the forefront of my work.

I am currently attempting to engage all of the mixed identities I carry visually in painting. I feel we are also at a crazy point in time when these hierarchies between design and art are beginning to unravel to some degree because of the scarcity technology has created for people and object makers to operate in the physical realm. We’ve also seen so many periods over the course of art history, that I think negate these lines of separation, such as periods like the Renaissance, where a majority of works were commissioned solely based on technical ability.

We’ve seen “de-skilling” in abstract painting, and the resurgence of the “crafts” again. Yet, there remains this conversation of what should be excluded in art.

Personally, I see a wealth of artistic value in signs as a subject matter. There are both conceptual and technical areas to study, from the fluctuating politics of our visual landscape to the technical lineages of painting, so there is a lot I feel a desire to document. I’d love for my role as a painter to become a force that delineates these boundaries.

@Spooky_Orbison // This interview was originally published in the Winter 2024 Quarterly