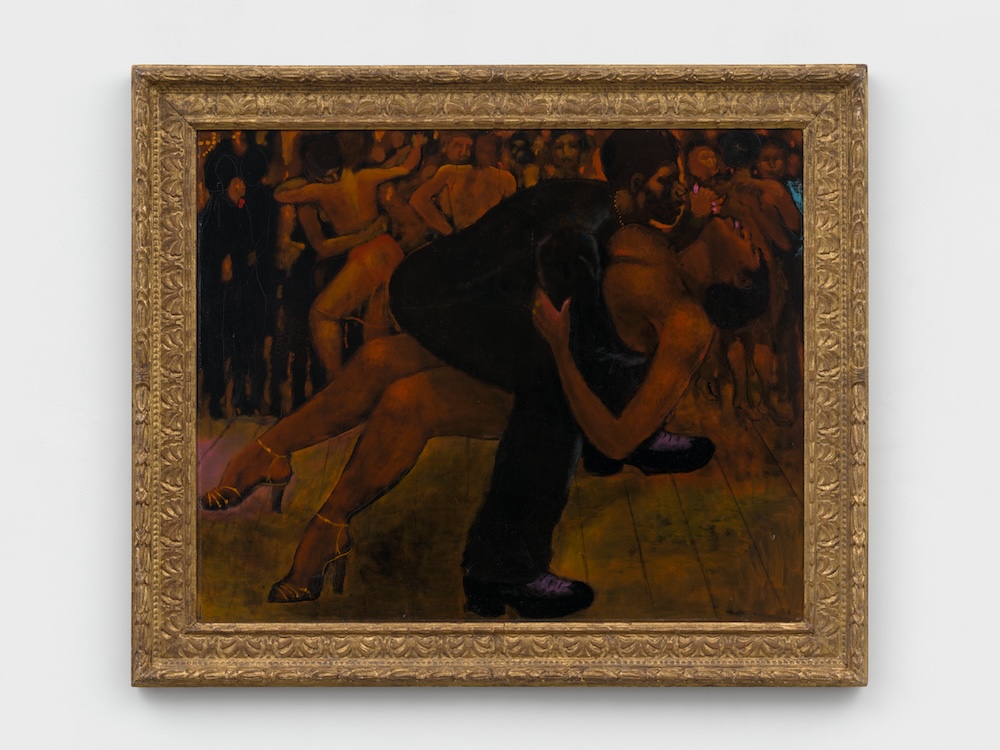

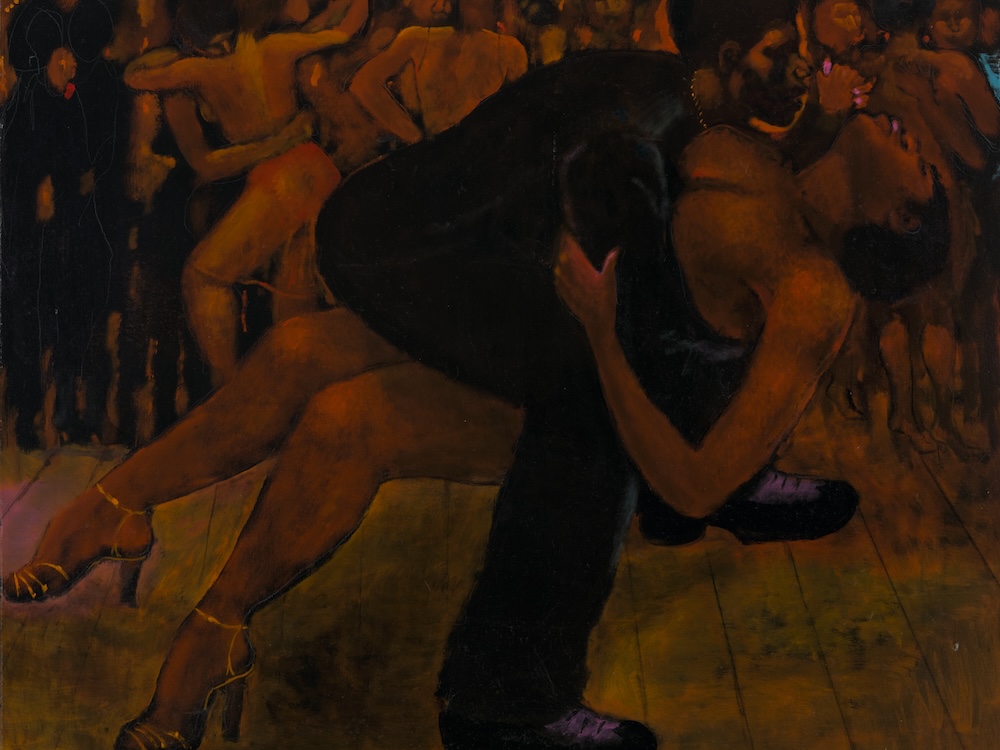

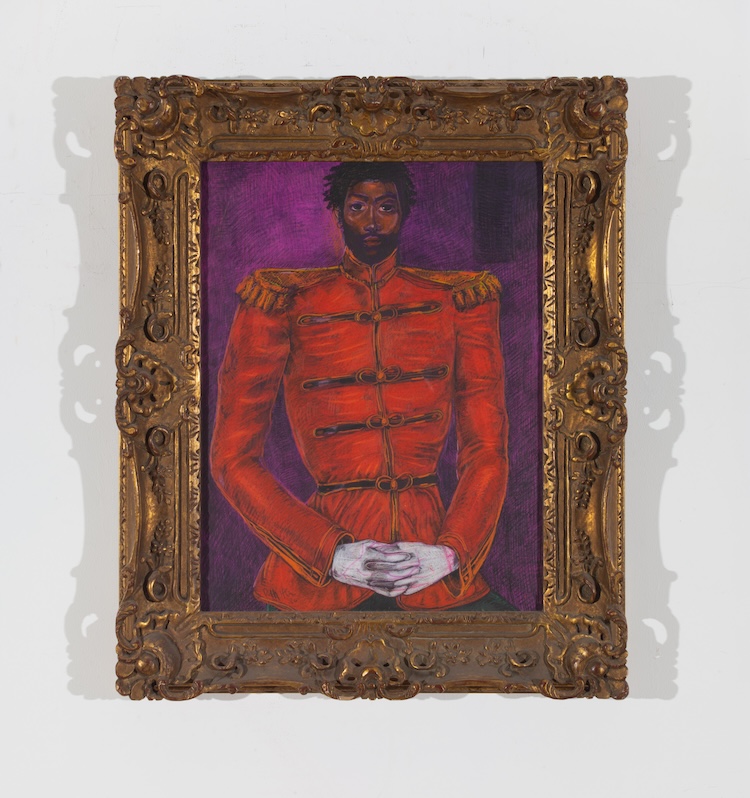

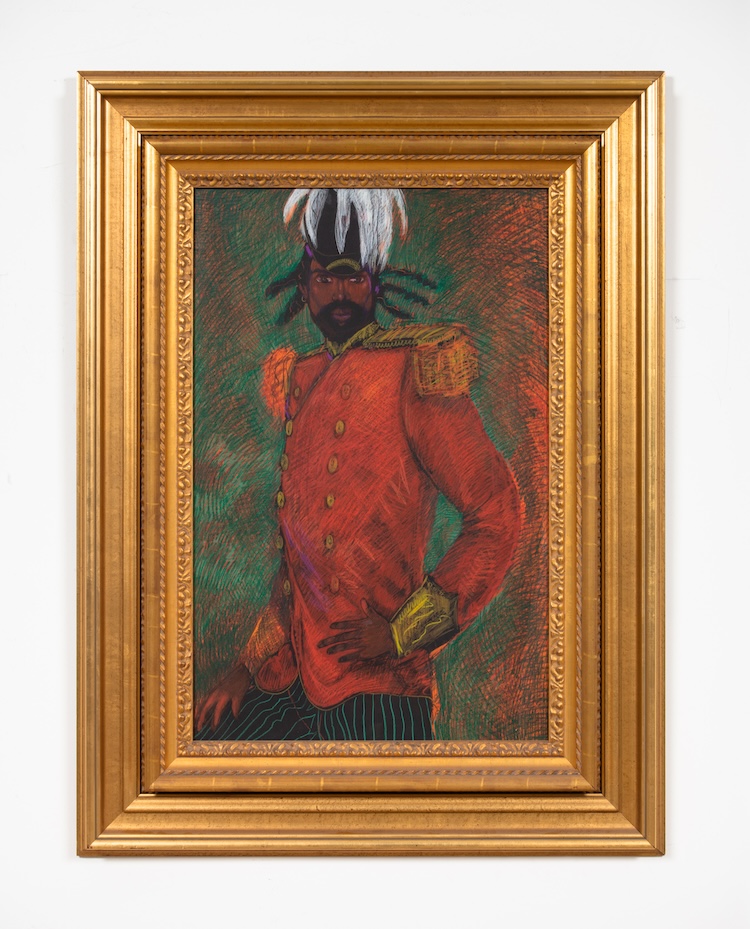

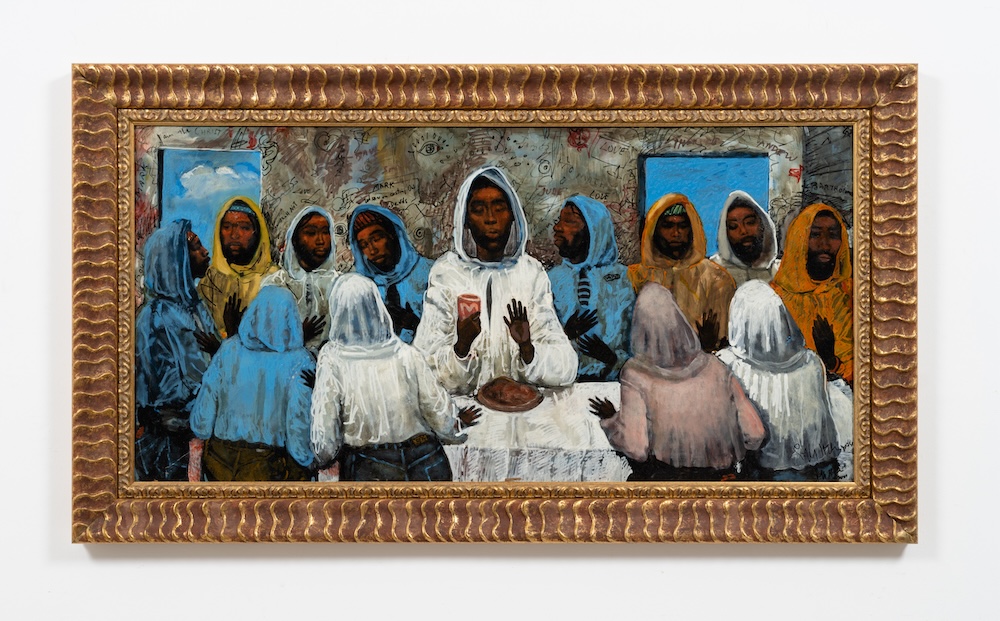

There are an incredible amount of works inside the James Fuentes Gallery in Melrose Hill, which is now showing the artist Geoffrey Holder. When I use the word “incredible”, I don’t mean it lightly. Both in size and scope, every piece in the show feels powerful, a place where you could spend hours gazing with jaws dropped at what feels like an intimate behind the scenes of the spectacular life of Geoffrey Holder.

This is the first time that Holder has had a solo exhibition in Los Angeles–and whose work was also on view as one of the best booths at last week’s Frieze LA. “We come here thinking that we need to introduce the work–which we kind of do. But I’m also excited to see what we can unearth about the impact that Geoffrey has already made,” shared Fuentes at a walkthrough in the gallery space.

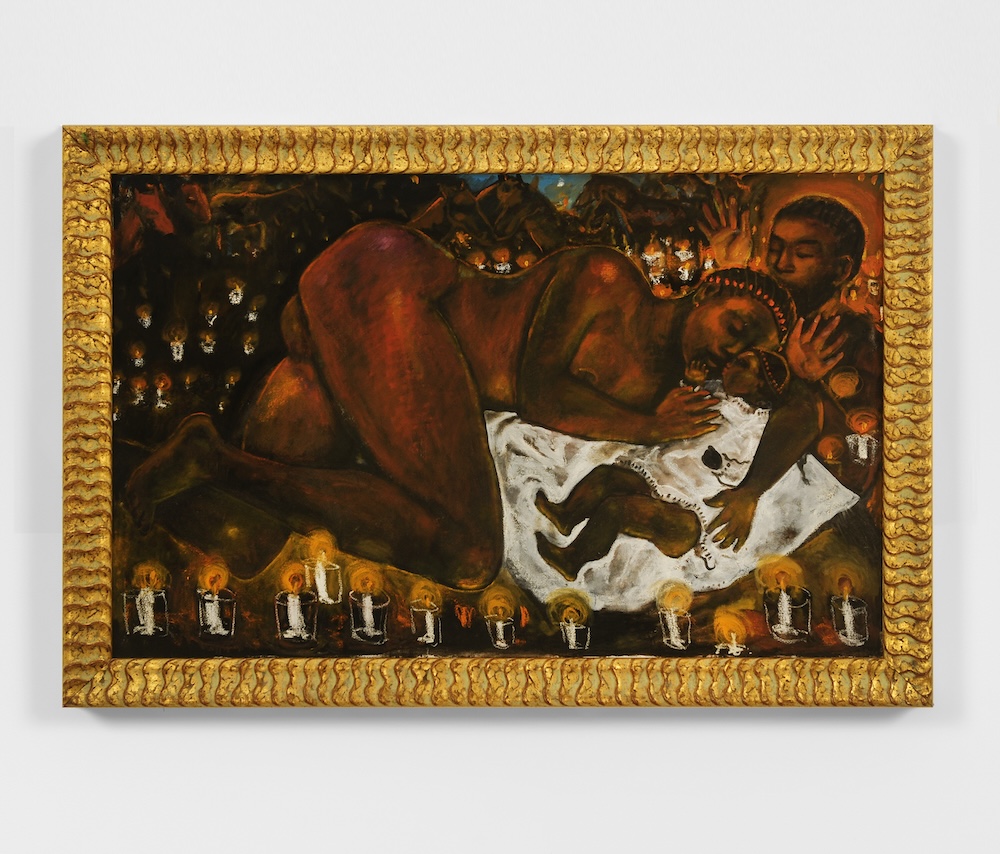

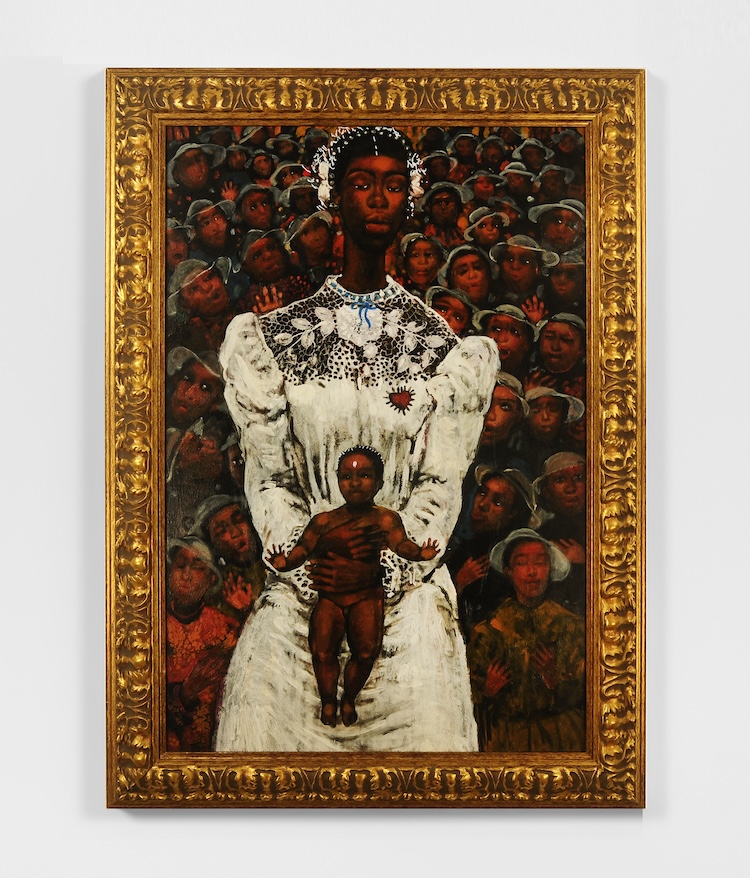

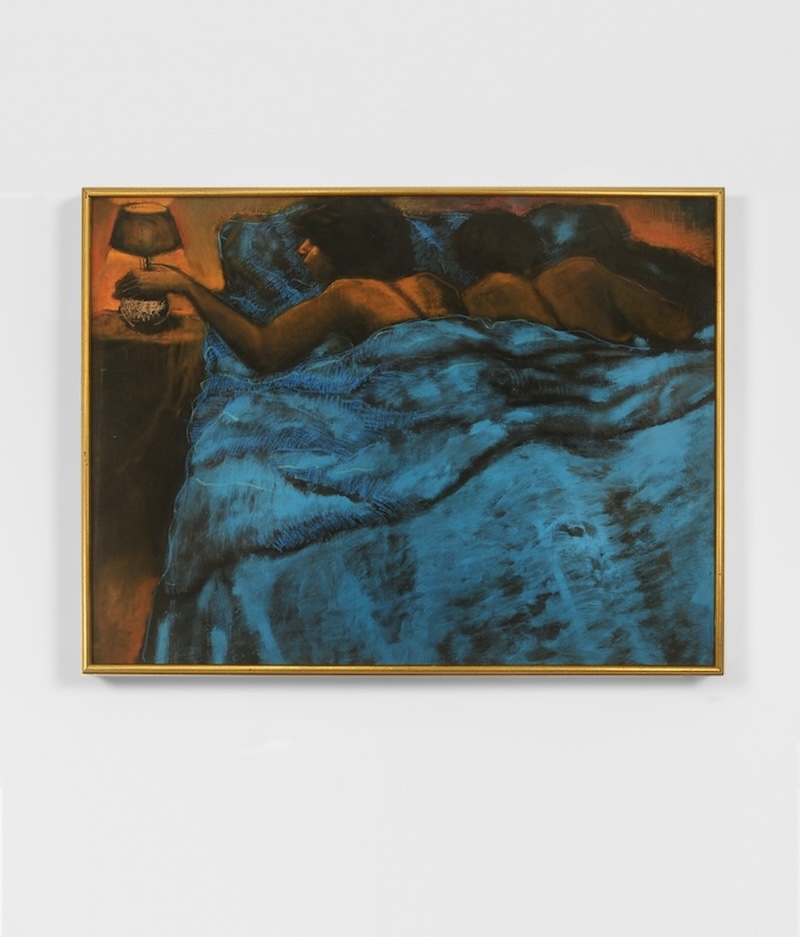

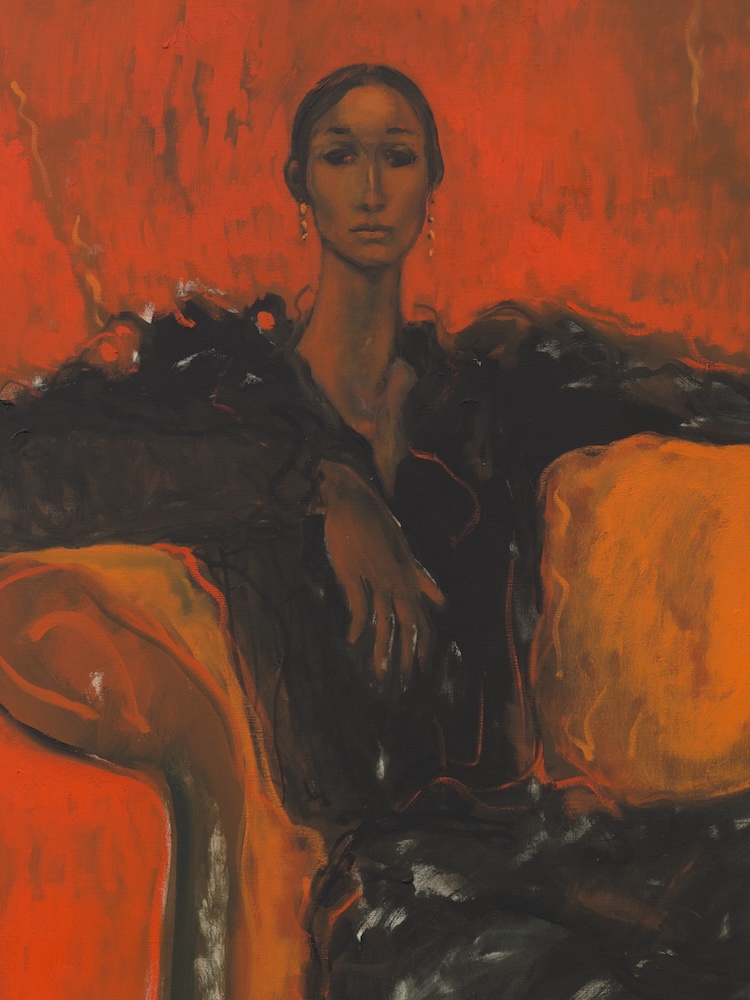

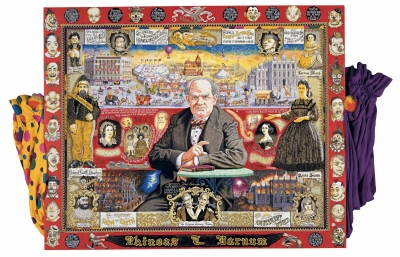

Holder was a multifaceted man–a dancer, choreographer, actor, composer, designer, and for all intents and purposes, an artist. He won Tony Awards for his direction and costume design for The Wiz. He danced on Broadway and at the Metropolitan Opera. He had a 7Up commercial that still jogs a happy memory for many. His art in every form was the totality of Black life.

And as such an accomplished man, he ran in the circles of creatives that have guided my entire life. He spent time in Paris working with Josephine Baker. He directed shows with Patti LaBelle. He was roommates with Alvin Ailey–and this Fall, Holder’s paintings will be included in an exhibition at the Whitney Museum that reflects on Ailey’s life's work called “Edges of Ailey.” All of this inspired Holder, and in return, he inspired them.

“He and his generation were very much recognized and embraced by the generation of the Harlem Renaissance,” shared his son, Léo Holder. “And not for nothing, but the main players of the Harlem Renaissance were alive until the 1960’s and 70s. The Harlem Renaissance never really went away. It just progressed. And it progressed into this.”

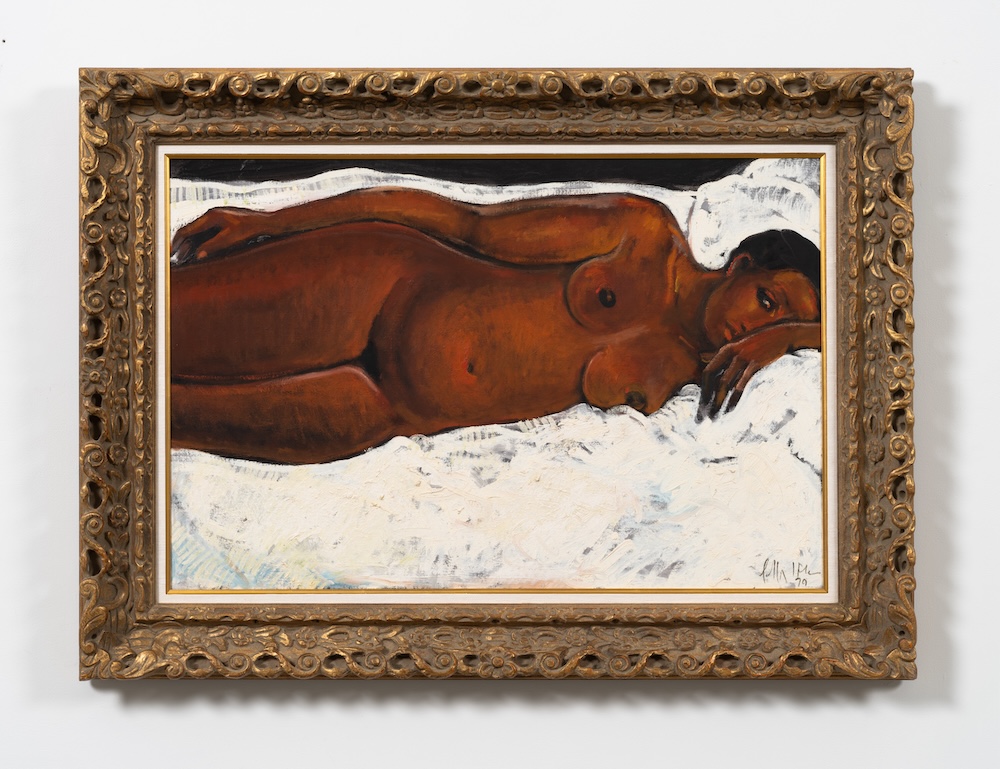

Throughout his entire life, Holder never stopped making art. “His costumes, his choreography–they’re all through the eyes of a painter,” said Léo. He also shared that on view at Fuentes is the last piece Holder ever touched before his death in 2014, Maria Virginia. “We had a small exhibition… and he’s in his wheelchair looking around saying “good, good, good” and then he gets to this one. He asks one of his buddies to go down to 13th and Broadway where there was an art supply store, asking for a white paint marker. I thought, “Are you kidding me?!” He took the white marker and gave her some accents all around. Because when he had done this painting, which was several years earlier, he just had these flowers on the back of her head. But he said, “By the time I looked at it several years later, I thought they looked too much like headphones.””

When the walkthrough was over Fuentes talked with me over a catalog on Holder that the gallery had placed at the front desk. As he scrolled through the pages, pointing out Holder’s costume designs, photos of his Léo as a child in front of his fathers artworks, Holder dancing at parties and holding glasses of wine, I could feel both the excitement and reverence that permeated not just from the paintings, but within the aura of his legacy.

“The fact that in his time people thought, Who does he think he is? His bold statements were rejected–which doesn’t surprise me,” shared Fuentes. “But now, it’s just interesting to see how much society has changed. For me, the remarkable thing is, the context to receive and analyze and appreciate this work… the fact that he never found it in his lifetime blows my mind. I think that’s the magical opportunity that we have now. We’re in a time where this work can actually really do what it needs to do.” —Shaquille Heath