Certain scents ground us into a place, letting us know where we are even when, cognitively, we already know. Petrichor is one of those scents for Santa Fe-born artist Madeleine Tonzi. The mix of sage, piñon, and soil lifted into the air by the fall of the first rain conjures deep, emotional memories tied to growing up with a place—the type of scent you don’t always notice until it’s no longer a part of daily life.

As humans continue to impact the environment, releasing pollutants into the ocean and the air, these scents that arise from the soil will change; an invisible part of the landscape is dissipating, and we, the ones who will miss it, are the ones to blame. This grief that emerges when we must leave a place for environmental reasons and the love we feel that pulls us to preserve a place are a central themes in Madeleine Tonzi’s new series of paintings and monotype prints. Before opening her solo exhibition Petrichor at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco, the artist sat down with the gallery’s Katherine Hamilton to discuss attuning herself to a place, artworks as portals, and human-land relations.

Katherine Hamilton: For the past few years, you’ve been thinking through the concept of solastalgia, the stress one feels during environmental change that impacts where one lives, and Soliphilia, a love of all aspects of a specific place. Can you say more about the concepts and why you’re gravitating towards this love of land lately?

Madeleine Tonzi: Both terms were coined by Glenn Albrecht, an environmental psychologist from Australia. They were created in conjunction with one another, with soliphilia being the antidote or opposite to solastalgia. “Soliphilia,” Albrecht writes, “is the love of the totality of our place relationships, and a willingness to accept the political responsibility for protecting and conserving them at all scales.” I realized that for most of this time I was dwelling on solastalgia and these feelings of loss in the wake of climate change, industrial extraction, and natural disaster. Yet an aspect of my work has always been an attempt to convey a sense of beauty and awe for that which I love. I think it is fair to say that my work encapsulates both concepts, as I grapple and contend with the issues of today. I always include subtle nods to the complexity of my experiences through color and symbolism, and that is a tension I enjoy exploring. Still, it seems appropriate to include other concepts that instill hope, and we desperately need that right now.

The works in Petrichor gravitate around our love of particular places and connections with the land. Can you describe a time when you felt wholly in tune with a place? What did you notice about those moments?

I feel wholly in tune with a place when my senses are fully engaged, and I am present and acknowledging everything around me. When I return to Santa Fe, where I grew up, there are elements that root me to where I am—the smell of the air, the mountains, the ponderosa pines and aspen forests, the food and the people. Santa Fe feels settled into the land. The architecture blends into its environment, and the lighting there is pure magic.

How do you turn yourself to a place?

Being in tune with a place... I think it has to do with familiarity, especially within city environments. Getting to know visual markers and what I have always referred to as my neighborhood song. In some places that I have lived, the song included the push of a shopping cart as people collect recycling, and the sound of food trucks jingling at specific times of the day. In other places it’s been the whistle of a train and fog horns. When I’m grounded in nature, my senses are connected to the living world around me. Those attunements are when I become aware that the animals and plants are equally aware of me as I am of them, and that I am small in comparison to the magnitude of that which surrounds me.

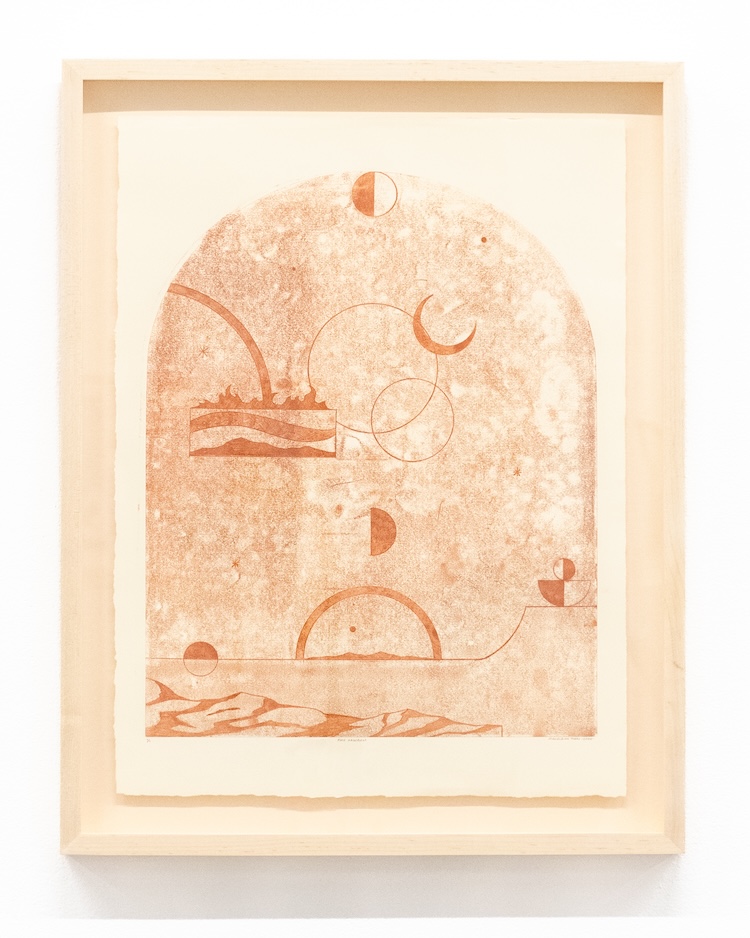

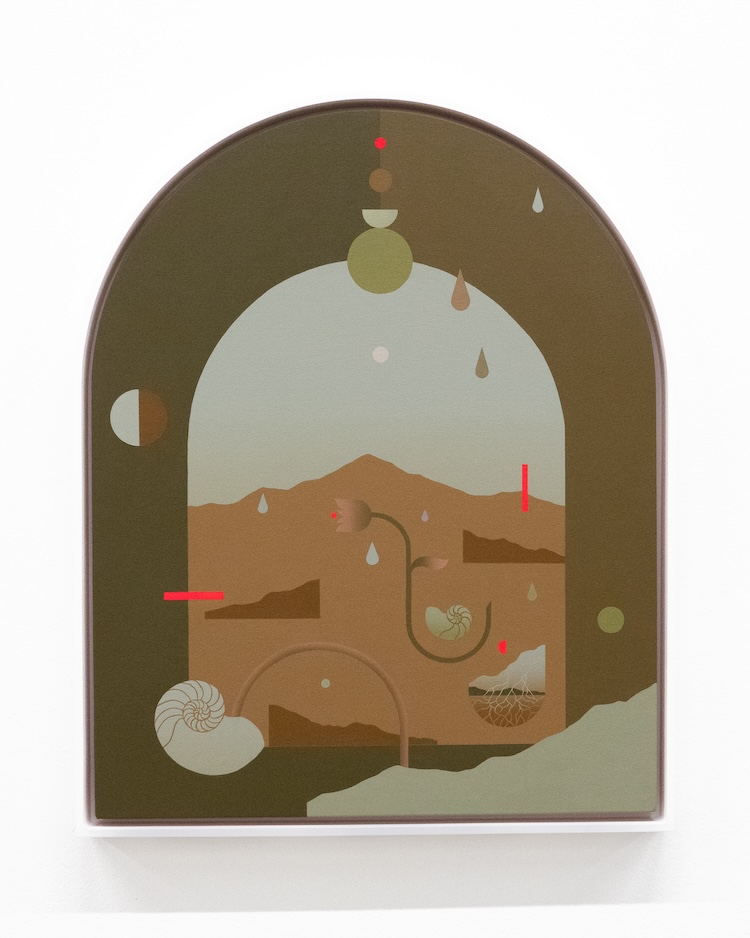

Many of the artworks in this show are in the shape of archways. Why was this form something you wanted to explore?

I have always been fascinated with the symbolism of portals as passageways for new possibilities, as well as a delineation between the inner and outer, within and without, and a separation between (or framing of) the built and natural world. They are a window into what could be, as well as what binds and constricts us. I am interested in the intersection between the human experience and our built world. How does the interplay between architecture and the natural world coalesce? Does it inhibit or encourage us? The arch shaped canvases lend a dynamic dimension to the concepts I’m exploring by expanding beyond the pictureplane itself.

Within your work, the integration of gateways or other structures that denote a passageway seems to give the idea that we can deconstruct the systems that frame nature and the environment as easily as we have constructed them. Do you feel like you’re interested in construction? Deconstruction?

This is such an interesting take on the work, and one that I haven’t actually considered before. I can’t say I am an expert on the theory of deconstructionism and constructionism, but I am interested in them to the degree that they are akin to natural cycles and offer a metaphorical lens to view death and rebirth, a process deeply embedded within existence and replicated across systems and social structures. The universe was formed through violent explosions, resulting in the delicate abundance of life as we know. It’s necessary for us to deconstruct in order to understand and reconstruct new possibilities and ways of thinking and living.

As I understand it, one of the core principles of deconstruction is acknowledging various ways of thinking and approaching a subject. Instead of a monolith, there are a multiplicity of solutions and methodologies, inside which lies an ecosystem of interwoven realities. A broader way of looking at this is through the lens of composting. The process of decomposition and rot contains the ingredients for regeneration. What’s fascinating is that this process is dependent on a network of microbial organisms—such as worms and mycelium—that collaborate to break down, deconstruct, and ultimately give way to fertile grounds and the possibility of new life.

To your original question, I am interested in the relationships and networks that are formed in the midst of these processes of decay and regeneration, deconstruction and reconstruction, because it is within these alliances we begin to see an emergence of new systems and possibilities.

There seem to be a lot of flowers in this body of work. Can you say more about why?

I wanted to expand on my visual language within my worlds and diversify the composition. Flowers, shells, cactus are all elements that exist with the landscapes I inhabit, and so naturally it felt right to introduce them into my paintings.

I’ve been thinking about the difference between environments and ecologies. Your works bring this to the front of mind—how the macro meets the micro and where they begin to affect each other. Your works seem to have an ecological component with all these different shapes floating around.

There is definitely an emphasis on ecology in my work. Worlds within worlds; the micro and the macro; each element in relationship to the next. Relationships are a big part of the work: The mountain in relation to the moon, the moon to the Earth, the flower to the window or the sun. I love playing around with the juxtapositions between all of the elements. The seed levitating from the flower is also a sun or moon; the horizon is in the distance or sometimes contained within a vessel. It’s this interplay between each element that defines it, just as we are defined by one another and the world around us. When we start to think about the relationality of everything we are reminded of how interwoven our existence is, and thus how important life is down to the elements. I think about this a lot in the context of our sense of place and love for the land. The more we pay attention to the minute, the stronger the relationship we form to it and the more we care for it.

The color palette features a lot of browns, chartreuse, and dusty pinks. I feel like your palette often coincides with current concerns about the environment—I remember you saying the neon red bars in the Life on Mars works from 2020 were like temperature bars to signify the urgency of the climate crises. Where are these colors coming from?

Petrichor is an almost synesthetic experience and conjures a strong correlation between scent and color for me. In the high desert, this is the scent that saturates the air after it rains. The smell is rich with the aroma of sage, wet soil, and piñon. The phenomenon invokes for me hues of sage, ochre, raw umber and burnt sienna. I settled into that vision, and that is how I landed on this selection of colors. I still use the fluorescent red accents to symbolize a warming planet. It feels appropriate that a synthetic color would represent that. It contrasts with the softer earthy hues in such a mesmerizing way, and yet it’s jolting and somewhat unnatural. It’s this tension that I like to play with within each piece. It’s beautiful and contradicting all at once. And sometimes that is the strange position we find ourselves in during these times.

In a recent conversation with my mom, she made a remark that I was painting the California smog in reference to my gradients. While it wasn’t my exact intention, the conversation recalled an article I read which refers to a recent scientific study showing that the dreamlike sunsets portrayed in the paintings of impressionist painters, such as Claude Monet, were actually depictions of pollution caused by the industrial revolution. I suppose my colors and techniques reflect my surroundings, even when it is unintended.

You’ve also released prints with Hashimoto Contemporary on the equinoxes and solstices. These days that note how long the sun is in the sky were important time markers for ancient societies, but in modern society, they’re just another day! Why are these days special to you, and can you tell us a bit about the prints in this series?

I was born on the summer solstice, and so the quarterly cycles were ingrained in me from the start. Growing up in New Mexico, I was always fascinated by the night sky and the turning of the seasons. I think everyone has an innate sense for this, but modern life often extracts us from the rhythms and cycles we were attune to for millennia. Light pollution, industrialization, capitalism, hustle culture, all of these things have extracted us from knowing the Earth’s natural pulse and how our bodies respond to changes.

I wanted to create a series of prints about the seasons and their appropriate solstices to honor these cycles. Life is often overwhelming and speeding by in ways that we can’t control. By slowing down and taking note of the shifts in season, we can find ways to resist fast culture and reconnect to the world around us and our sense of place within it. The Solstice print series is a visual ode to that notion. It’s my way of interpreting each season and honoring what they have to offer. The designs employ colors and imagery to correlate with the corresponding time year. For each series, an edition of ten hand embellished prints include metal leafing. Spring included mixed metal leafing, Summer will be gold, Fall will be copper, and Winter will be silver. A lot of thought and intention has gone into each design.

Your current exhibition with Hashimoto Contemporary is titled Petrichor, after the aroma that arises from the ground when it rains after a long drought. What are other sensory experiences that help ground you, and where do they take you?

One of my favorite times of the day is magic hour or golden hour, right when the sun rises and just as it’s setting. I always think of this time as the time when plants speak. Under the dimming light, the flowers glow with an intensity that appears like an aura, and their aroma permeates the air. There is a stillness, yet everything is amplified. This can be accessed anywhere, and I have found it to be a good way to familiarize and ground myself within a place. Most of my paintings attempt to illuminate this experience through color and gradients.

In your writing for this show, you said the work gravitates around a single question: Are we in right relation to the land, one another, and our sense of place? Moreover, what elements collaborate with us to forge these relationships, and how can we safeguard them for future generations? I’m curious how you might respond to these questions guiding your work.

When I consider this question of being in right relation to the land under the system in which we currently live under, what comes to mind is that it takes place on a spectrum, both in small and big acts across cultures and communities and individual lives. I wouldn’t be honest if I said outright that I am in right relation to the world. However much I strive to be, modernity has its guardrails and limitations. Ultimately I think the questions arise out of a deep longing to fulfill what I see as my responsibility to the land, people and our nonhuman friends and that it is a work in progress. It’s a question I think many of us are grappling with, and perhaps something many long for as well, and in small ways we achieve this in our daily lives, whatever that may look like to each individual.

Petrichor is on view at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco through June 29th. Installation photos by Shaun Roberts, opening night images by Kuan-Ya Wu