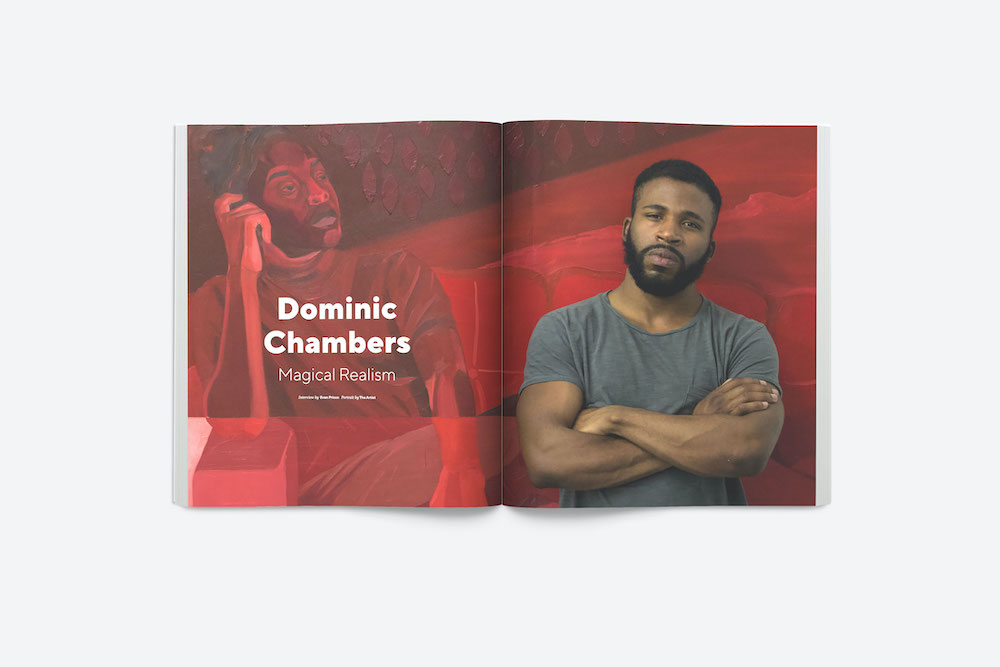

Kerry James Marshall is not featured this time around, but his presence looms large. He’s referenced, with reverence, by a few artists, Dominic Chambers, notably, but KJM’s powerful oeuvre and work ethic captures the essence of this issue in a way that I hadn’t recognized until the final pages were sent to press. Consider birdwatching. There is something so fascinating about observation in the activity; it requires acute, special insight and viewing intellect, such that I will always be drawn to someone who is an active birdwatcher, as I presume they have other in-depth insights into the world. Birdwatching requires another trait that is so ingrained in the American psyche that it crosses social and political boundaries, something that amazingly, set off an incredible social justice movement here. Birdwatching requires one to stop. Rest. Sit quietly. Patiently observe. These are opportunities not normally afforded to Black people in this country. As Tricia Hersey, a founder of the Atlanta-based Nap Ministry noted on NPR this summer, “Right now, rest is critical because it's counterintuitive and counter-narrative to see slowing down, napping and rest as a key to our movement for Black liberation. But it really is so important because rest disrupts and pushes back and allows space for healing, for invention, for us to be more human.” Does it surprise me that one of the great American painters of our time, Kerry James Marshall, would introduce to the world two fantastic new paintings on the topics of black birds this summer with David Zwirner, influenced by the John James Audubon’s nineteenth century magnum opus, The Birds of America? No, because Marshall is one of the great observers America has ever produced.

Of course, I immediately started to think of the origins of America’s new discourse on race, and how Marshall’s show of birds bookended one of the most contentious summers in American history. That we started with a tumultuous, racist encounter in Central Park involving a Black male birdwatcher and white female dog owner, whose use of social power structure sparked outrage and shock the week before George Floyd’s murder, propelled the conversation even further. Marshall doesn’t evade race, but elegantly inserts the tension within these interpretations of Audubon’s works. The works fact-check history, refuting falsehoods laid down by the so-called winners, as the artist speaks out with autonomy. He looms large in this issue because he is the master of critiquing art history while making art history, a process so immediate, yet so full of his innate patience and practice. We are grateful for the power of every artist in Juxtapoz, but it feels so deeply important to recognize his presence as we send this issue to print.

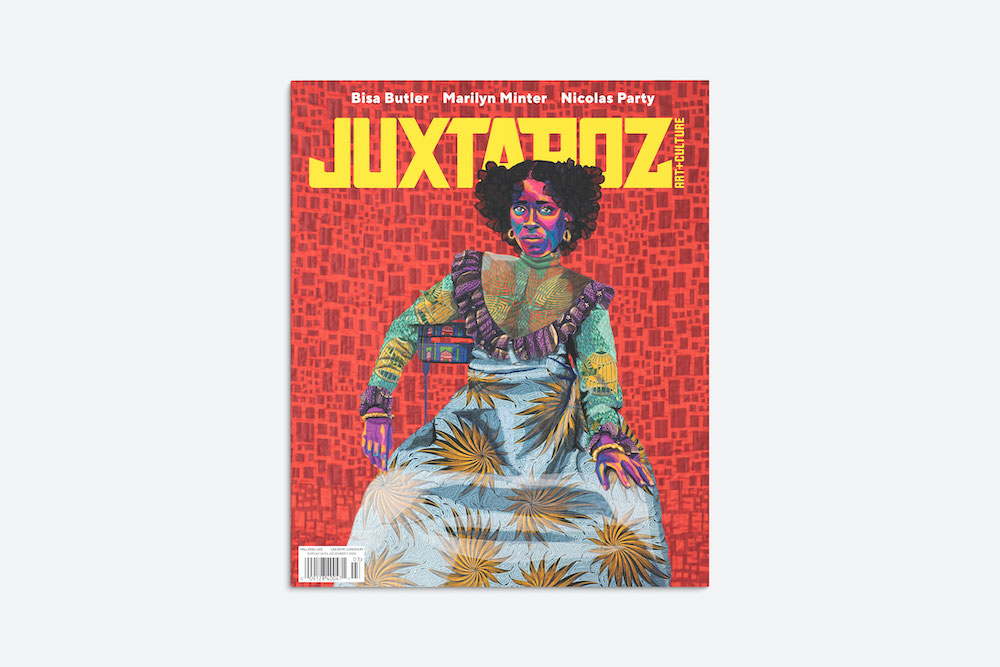

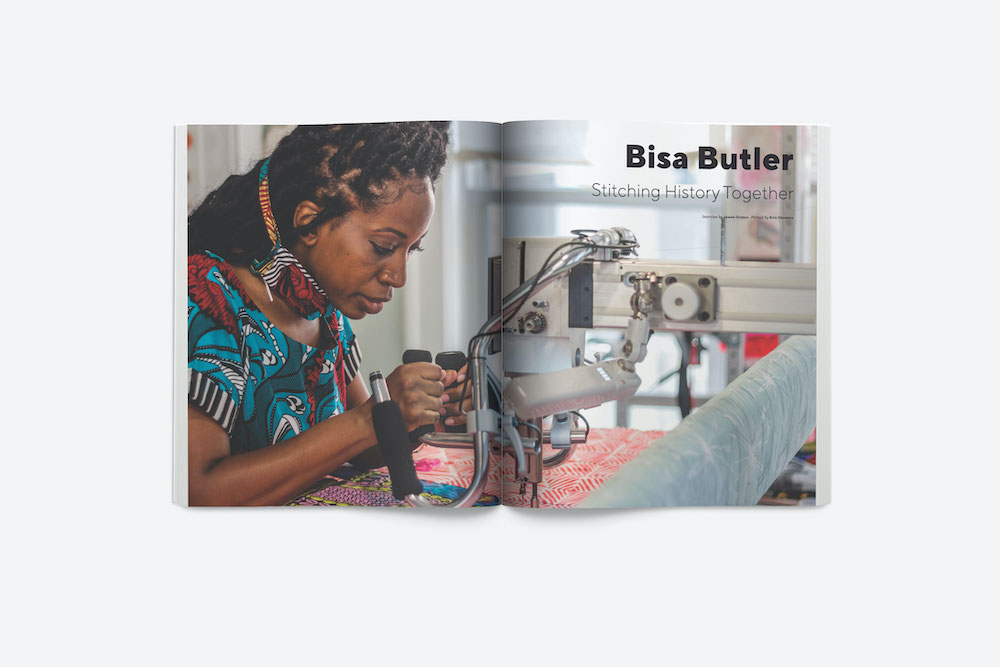

Bisa Bulter is indeed featured in this issue, and her presence looms equally large. That she is one of the first textile artists on our cover is special in its own right, but her concept of a beautiful, time-consuming, traditional craft art reimagines history and narration, declaring the truth of the American experience in a dazzling statement on the importance of art as a healing tool of communication. Juxtapoz has always been about the reimagining of style, technique, and craftsmanship, but most importantly, a democractic forum, open to every artistic style and status, encouraging conversation in the creative fields. A life of, and in, the arts is a possibility, and sharing that art history is necessary for a greater understanding of our global culture.

Three years ago, for the debut of our Quarterly iteration, Kerry James Marshall considered his work, and observed, “It's supposed to get harder, and that's not really a problem. You're supposed to be more sophisticated and much more self-conscious. As you know more, you have to consider more. It gets harder to make the next thing, because you have to have a good reason to do it.” There has never been a better reason than now. —Evan Pricco

Buy the Fall 2020 Quarterly here.