Our eyes evolved for light, but it is at its edges that we see most clearly. It is in the transformative glow of the sun’s predictable retreat and re-emergence where the world flaunts its beauty, where light meets darkness, that we begin to understand the shape of things. Our eyes may be blind in the night, but it is in darkness that long-dormant senses, like vestiges of some forgotten evolutionary path, awaken. The imagination indulges in the illusory void of darkness, uninhibited in the world’s apparent absence. For many, it can be a space of fear, but for Pia Paulina Guilmoth, it is a sanctuary.

Whether in darkness or light, with or without the comforts of sight, what we don’t see still exists; everything outside of the frame of a photograph is still there. But truths can be indisputable, and we still need safe spaces to consider them. Guilmoth, who resides in rural Maine, has long found solace and clarity in landscapes after dark, in space that continues to evolve in significance alongside her recent journey through transition. “I’ve always felt comfortable at night; I feel very at ease,” Guilmoth tells me. “Even before feeling like I was being watched for that reason, for being a visibly trans person out in the world, I think my fears have always been about people rather than anything that wakes up at night.” Darkness hasn’t hidden the world from Guilmoth; it has shielded her from it, enabling her to see the shape of things in the light of her own understanding.

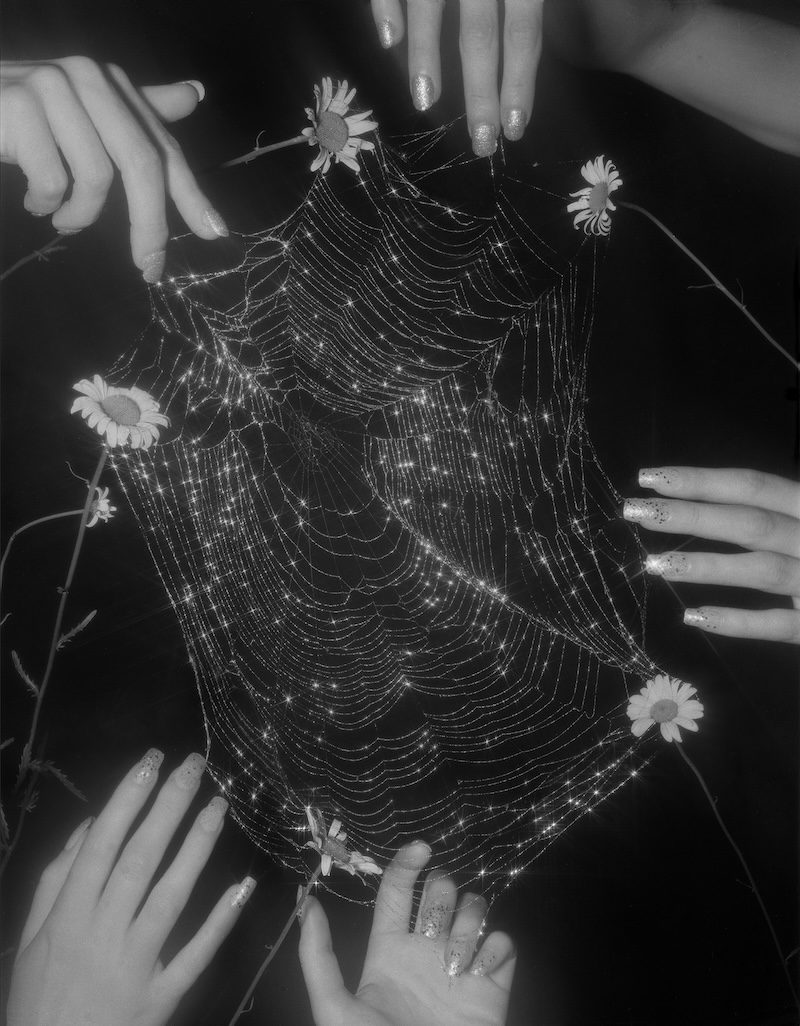

Just as the treacherous beauty of the spider’s web reveals itself only when caught in the glimmer of a rare slant of light, so too do objects in the world define themselves in our attention. “During the day,” Guilmoth explains, “I tend to take it all in rather than focusing on one detailed part of something. At night, there is more discovery. It almost feels like hidden treasure.” Perhaps it is because of its proximity to our dreams that nighttime embodies a certain kind of magic, allowing ideas hidden deep within the subconscious, obscured by the multitude of daylight's distractions, the space to grow. This nocturnal arena of symbol and mystery, nightmare and fantasy, seems to infuse Guilmoth’s photographs with their unique beauty, casting a dreamlike reverie even over those made in daylight.

In observing the world, whether within a moment of pause or the edges of a photograph, we discover both flaws and beauty, often one within the other. These very contradictions—the contrast between the two—draw the eye, often illuminating some sense of their essence. Guilmoth’s photographs are, in their core, an extension of herself. “Everything I do, everything I make,” she explains, “is very much connected to whatever I am going through at the time.” The images offer a spellbinding allure. There is a familiar tenderness, an aura of ritual divination, of the inevitability and potential of growth amidst an unpredictable environment. “I feel more in myself and in my body now,” she adds. “There’s a newfound joy that comes with photography and making art where I can put my entire self into it, not just part of me. I’m showing the beauty in the pain of life rather than it coming from a painful place.” It is where beauty meets pain that we begin to understand the shape of things. —Alex Nicholson

Pia Guilmoth’s latest book, Flowers Drink the River, is available for pre-order via Stanley/Barker. An exhibition of the same name will open at Webber Gallery in London. These images and text were first published in Juxtapoz FALL 2024 Quarterly print edition, courtesy and with permission from the artist.