Michael Jang's 70 years of age belies an unfettered youthful exuberance. It's clear that this is an innate aspect of his character, but one senses that the wisdom he has gained through the years also plays a role, fueling his recent surge of creative output. The last time we spoke he asked me whether I would rather experience fame early or put it off for fifty years. It was not a hypothetical question for Jang. At the time, photographs that had sat for decades in boxes were suddenly adorning the walls of galleries and museums. But, like the man himself, they didn’t remain idle for long.

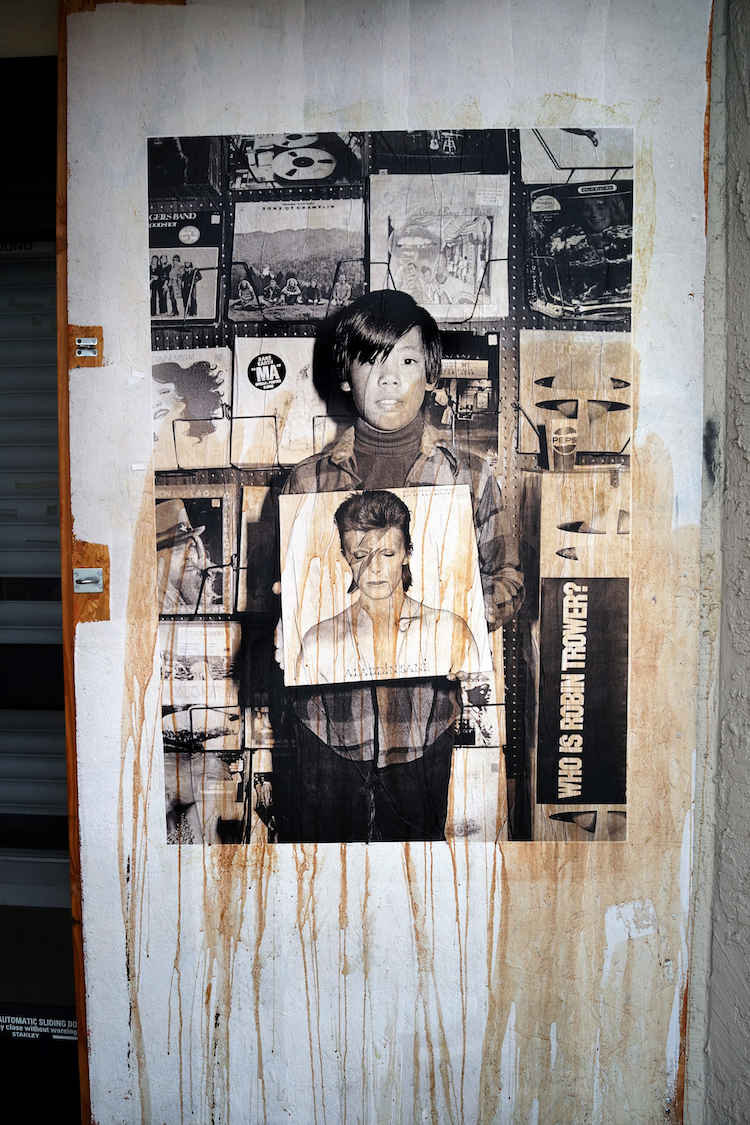

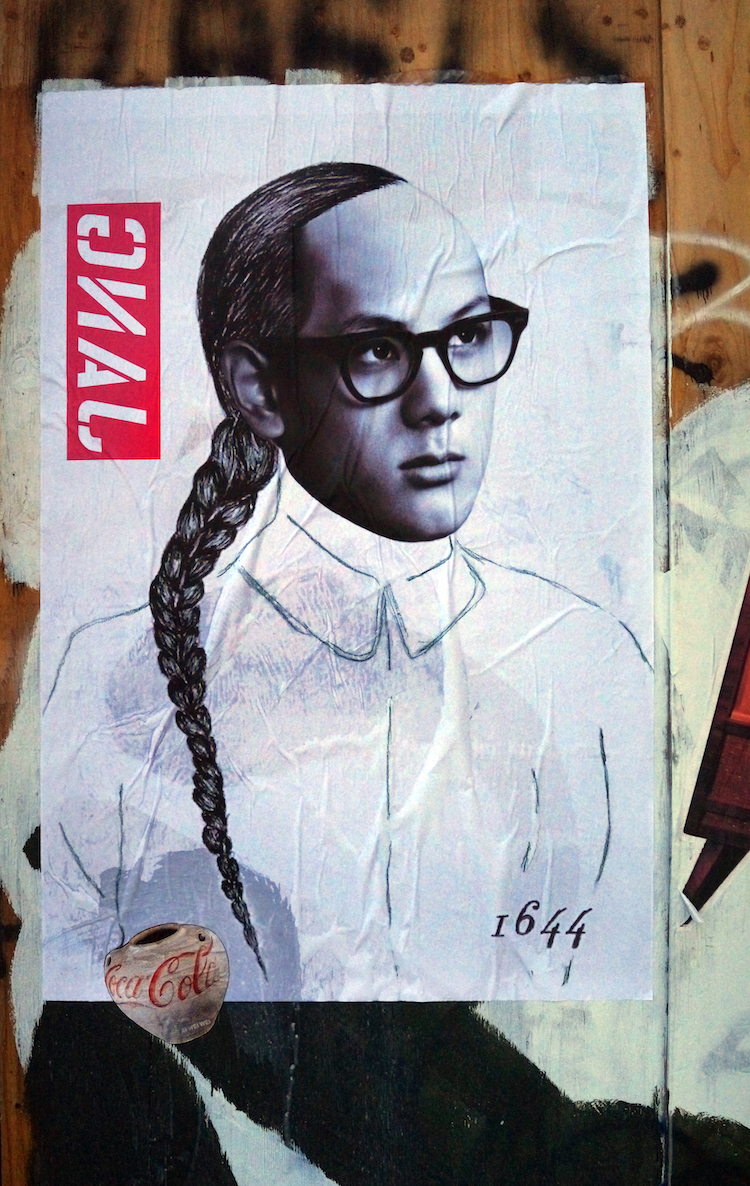

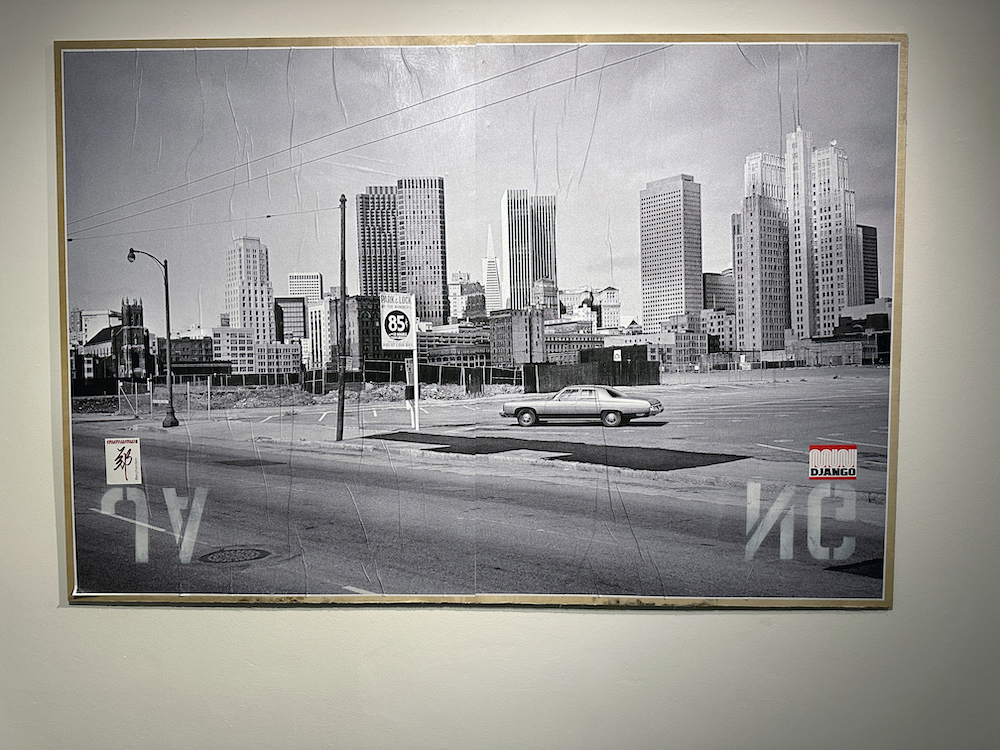

In the early days of the pandemic, Jang began wheat-pasting his photographs on boarded-up storefronts and abandoned walls around San Francisco, quickly introducing himself to the entirely new conversation that occurs when art is made on the streets. Much like his early photographs had been given new life, the raw, ephemeral nature of working on the streets reinvigorated Jang’s own relationship with the images. Late last year Yang’s photographs returned to gallery walls in this new form. What’s old became new, what’s new is old again and we continue to ask, “Who is Michael Jang?”

Alex Nicholson: So much has happened since we last talked.

Michael Jang: If I had only known retirement would be this much fun, right?

Before you seemed content with sharing prints from your archives but now you’re reworking and pasting them all over San Francisco!

It's backward in the sense that I'm already in museums with my fine art photography, and now after hitting the streets it’s gone full circle back to the museum! I don't know what to say except that it's fun and I'm in a completely different creative space when I'm doing it.

There's always been so much playfulness in your photography. This all seems to be coming from the same mindset.

Totally. I've always been mischievous. I like screwing around with people, throwing 'em off. I'm just a goof. So while I'm not taking pictures anymore or breaking into events with a fake press pass like I did when I was younger, I still have that same method of operation when I'm working on the streets. There's an adrenaline rush that comes with the unknown.

Did starting to work on the streets re-light that spark?

In the beginning, I was a little tentative, even a bit scared. We didn’t want to get caught but when we were done it felt really good. It was like we created a new way to have fun. When I try to do these things at home in the studio, I can't. It's not there... There is a magic that's happening, an x-factor that I don't have in my studio.

How often do you go out?

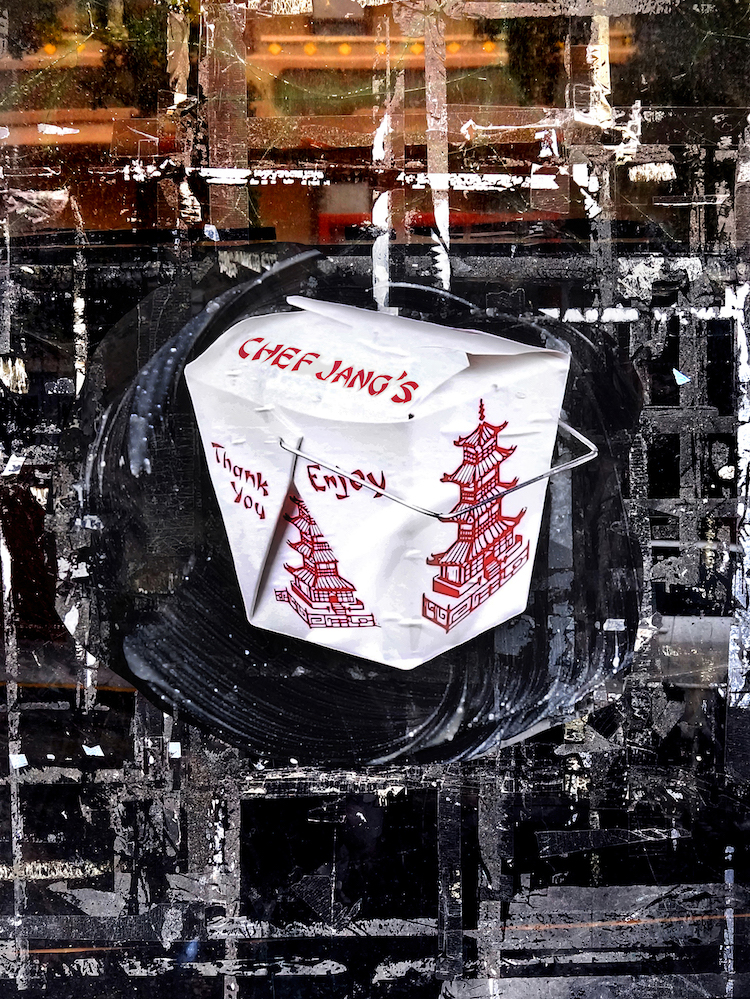

We go in cycles, maybe once or twice a week for a few hours. We've learned what neighborhoods are friendly—though some are pretty brutal. It’s such a serious world of tags and territory and all that stuff, but I really respect that and I love learning about it. Strike Anywhere Films is doing a documentary about me and one day there was a huge wall thirty feet from the police station, where we were filming, so I went up and started talking to the cop. I said, “Hey, man, I'm going to paste on that big wall over there, okay?” And he just said, “Are you that guy? We like your stuff.” I'm a made man in Chinatown.

So you’re no longer so worried.

I operate in plain sight from ten in the morning until one o'clock. I have lunch and take a nap, which is perfect for my age.

You started these wheat pastings at the time when there were those awful, violent attacks against Asians, specifically the ones in San Francisco.

Yeah, the beatdowns.

Was that on your mind when you started?

I always work with my friend and assistant Brent Willson. As a 70-plus-year-old Asian, I gotta be careful out there.

How interesting that it’s these old photos of yours that you're pasting up.

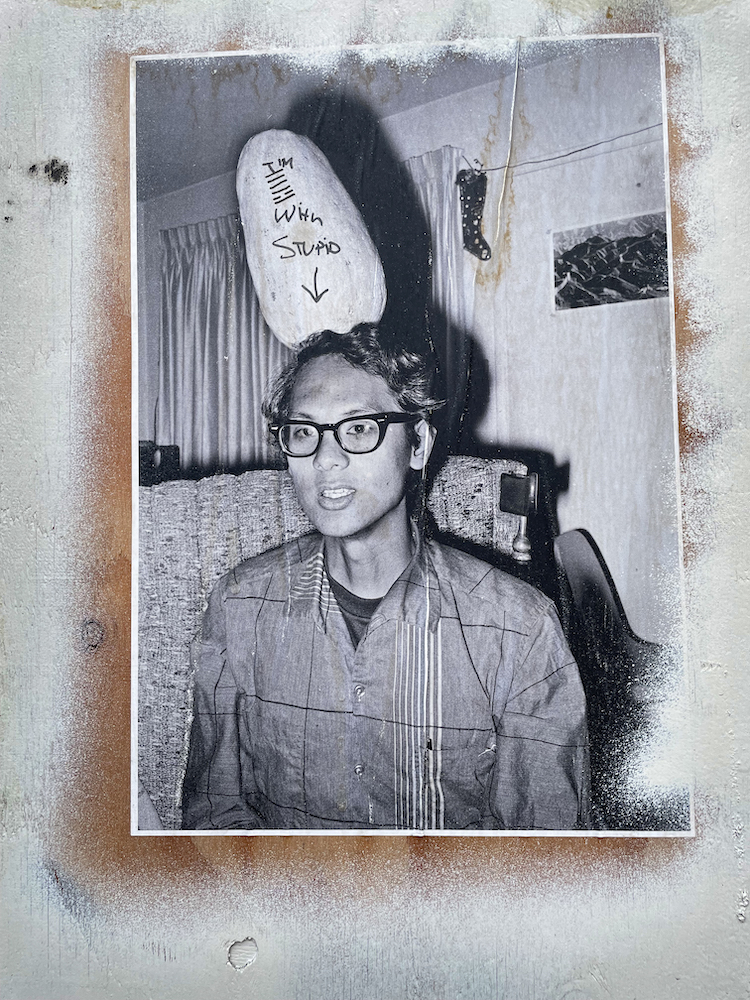

It’s like I’m an appropriation artist now but I use my own art from fifty years ago for source material.

It’s evolved quite a lot since you first started. You have a whole new following of people who have encountered your photography on walls and in the streets.

People see it and shoot it as their own artwork. They post it and tag me, then I repost it again and it’s become this circle. Only in retrospect am I reflecting on what's going on. And to be honest, I'm not sure where it's going, but I'm taking full advantage of the tools at hand. It's free and it's fun and has certainly kept me occupied for the last two years. No one was giving me a show so I just put the work out on old boarded-up storefronts that were closed anyway. This brings me to another point. The destination for this work seems to be the people—for free you know?

What feels most different about displaying your work in this way?

When you take a fine art, black and white photograph with a camera, that's one act of creation. But now I'm making compositions on a wall knowing that people will come by and photograph it themselves. I'm making compositions for them.

It’s not just for the wall, but for the photos other people will take of the wall.

Nothing lasts forever on the streets, I've learned that. The layers of the sun, sometimes rain, people marking on it or posting on top… there is a beautiful layering that's starting to happen. My photographs show that, ultimately, this is a project about collaborations; although usually, you know who you're working with. I don't know who I'm going to collaborate with and they don't know they're collaborating with me!

Do you go back and alter the walls at all?

Yeah, it’s the funniest thing. I'll put up two or three of my own things. People will tag and spray respectfully around it and the store merchants will buff the graffiti and leave my pictures. These are all things that I'm learning by just working and learning the rules of the streets. I've made a few mistakes but I try to be careful. At first, getting tagged over made me cringe, but now I just laugh and even appreciate it—all in the game, you know?

Do you think that if it weren't for the social media aspect you would still be enjoying it as much?

I don't think this dynamic that's happening between me and the viewers could have happened in the nineties or earlier. I've succumbed to the fact that part of life is this kind of virtual interaction. I can't imagine what it would be like to have none of that, just to have your prints at home in a box… which they were before this. Seriously, it’s the same images that have been in boxes for decades, and now it's out there on walls for people to see. I'm not sure where it can go. It may be over soon, who knows?

When did that feeling of being okay with not making new work transform into suddenly being inspired to make something new?

When Robert Frank did The Americans, it was a short period in the early part of his life. Did he do that for the next fifty years? No. Even though you may enjoy something or even be good at it when you're in your twenties or thirties, you don't have to do that until seventy. I'm presenting pictures from fifty years ago in a different way to a different audience. The demographic now is really wide, from teens to eighty-year-olds. I finally figured out that I don't have to make perfect prints with a mat and a frame on a white wall forever. That is still the foundation for everything but what I'm doing with them now is something wholly unexpected, even to myself. I am finding a way to measure my growth. It has to do with evolving by just working. That’s something all great painters would just tell you. Whether it's good or bad, you just have to keep working.

You’ve started to manipulate the images, not just pasting the photos as they were.

I print them pretty much straight at first and then will add layers to them with my own spray cans or oil sticks or other pictures. I have all these fake personas now, like Chef Jang. I have this Tai Chi master thing that I'm working on now too.

You seem to be discovering the fun again in how you relate to these images.

I've learned that mistakes are gifts from the gods.

How has your relationship with those images and the memories changed?

They're the same. When I'm shooting, I'm not even looking at what I'm taking a picture of or what it's gonna mean. I'm just trying to get all these things in balance. And to do that, you can't really think about anything. Time for a sports analogy. Steph Curry is possibly the greatest shooter of all time. When they show him on the bench everyone else is watching the game, following the ball. Curry is sitting, eyes wide open, not blinking, as if in a trance, staring at the floor. It cracks me up because I know exactly what's going on with him. He sees nothing yet he sees everything. He thinks of nothing, he thinks of everything. Very Zen.

Have you noticed similarities between how you feel photographing and how you feel wheat pasting?

I work really fast now with many pieces at once. We're not thinking intellectually. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't. There's a thing in Tai Chi called pushing hands. You don't punch people but you just try to move people and yield and get out of the way. If you think at all, you're screwed because it creates tension. You have to be nothing. It’s like water; you can't push water, you know, or wind, yet those two things are the most powerful elements.

How has your Tai Chi practice affected your photography?

I started both at Cal Arts in my first year. We're at fifty years now, so maybe there's a connection. I never thought about it too much but maybe it explains why I never pursued fame. Here I am doing this thing where you're supposed to try to make a name for yourself (art photography) and yet learning from Tai Chi about being nothing, subduing the ego. I was doing both of these things at the same time.

And now that you’ve found some fame and success.

It's great. I don't take it for granted and I totally forget about it. I haven't thought about that mural I did at SFMOMA for weeks!

michaeljang.com // This article was originally published in the Spring 2023 Quarterly // Photos in the body of the post by Alex Nicholson