We all go through life with our daily routines. I’m not here to tell you to snap out of it or be guided by major philosophical thoughts in everything you do because I’m sure Sartre and de Beauvoir spaced out on the way to the grocery store. But think about that awkward feeling when, all of sudden, you think you are on candid camera.

In the midst of a lackadaisical act of walking to the corner store, hypnotically going through the motions of passive shopping, you grab a felt candy bar and try to buy it from British artist Lucy Sparrow. Yes, it’s made of felt. This has happened, and you are now part of the installation.

In creating bodies of work that consist of 4,000-plus items made entirely of felt, whether a corner or gun store, or a full sex shop, Lucy Sparrow’s constructed experiences have the ability to reimagine the routine. I understand how one could accidentally take a felt candy bar to the cashier to buy a snack, and I also get that not everyone thinks art exists in this context. With her successful installations in London, Basel, Montreal, upcoming solo show at Lawrence Alkin Gallery, and recent Kickstarter campaign to launch a felt corner shop for NYC in 2017, Sparrow has built a career with this unexpected material, all the while keeping a studio practice in a way comparable to a fine art painter.

Lucy and I met at Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery in London to visit a Jeff Koons exhibition, which seemed quite appropriate given her love of sculpture. But something else made meeting in this place so perfect. Surrounded by the enhanced realignment of everyday objects from Koons, or the pharmaceutical brightness of Damien Hirst’s restaurant, there is this feeling of displacement among the familiar, something that Lucy Sparrow does so well. The routine gets dissected.

Read this interview and more in the November 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, available here.

Evan Pricco: You told me something about a felt sandwich bar for SCOPE Miami Beach this year.

Lucy Sparrow: I'm doing a whole installation, dressing it up like a Subway. A felt Subway. It's just an installation. It's not selling. It's pure installation, so people can come in and interact with it. You can buy things, but I just don't think people will be into that as much as they will be into looking at it. It's going to have this vibe of, "No, we can't serve you right now. We've got a million orders for bagels for Art Basel. We're very, very busy. We've got no more gherkins."

Is somebody going to be answering questions for you?

No. I think I should just shrug and say things like, “I'm afraid I don't have the authority to answer that. I'm just here for the sandwiches. I'm only here chopping the luncheon meat.” It'll be Lucy's Deli, so people will actually come to get sandwiches, and it's like, "Fuck you, they're not real."

When we had our newsstand at Scope a couple years ago, people definitely asked if we had cigarettes. You're like, "Seriously? It's a damn art installation. You're at an art fair."

They're so in the zone. That's the best thing. Not only are they going there because it's like a supermarket for art; they're there to be catered to. We're not there to cater to them. We're there to take the piss out of them.

What’s going into your solo show at Lawrence Alkin in London in November?

It's a show called Shoplifting, and it's sort of influenced from my times working in shops and seeing what items got nicked, stolen. It's a mix of one-off pieces and cabinets, but all the cabinets have themes. The new release for the show is going to be a “shoplifting” cabinet, full of things like anti-aging cream, razor blades, vodka, batteries: all the things people tend to put down their trousers and steal from shops.

So, the universal things people steal that aren't glamorous at all.

Exactly. The show is going to be super bright, not quite as heavenly or kitsch as the other shows I've done. It's going to be a bit more gritty, a bit more down to earth, and a bit more like, "Why is this happening?" Lots of cameras everywhere and security barriers making sure you don't leave or nick something like felt batteries.

We're almost ten minutes into this conversation, but we should address clearly that you make everything out of felt.

Yes. Absolutely everything.

Okay, work with me here: if you were an Olympic athlete, what would you be?

The only things I'm interested in are the diving and the gymnastics. I'm not interested in anything else. I'd definitely be a gymnast, without a doubt, or synchronized swimmer, but I actually can't swim. I'd die. So, gymnast.

The reason I ask is because what you do is a mix of repetition and perseverance. After you come up with a really good idea, it's this continual act of making similar, or the same objects, over and over, and it's also about your relentlessness in doing it for a really long time. It's a multi-hour-a-day activity.

Oh my God, yes.

Explain how you create all this work. What’s really interesting is your persistence, quite like the act of painting or gymnastics.

It 100% is. I went to an opening the other day, and someone asked, "Do you make all your stuff for a specific destination?" I said, "Always." There's never any stuff that I make that hasn't got a destination in mind. You start off, and everything is planned five to ten years in advance. It's so mapped out. When it comes to crunch time, hours in the day are divided up to... I know it's not what people want to hear, but it's anal. You do have to be super, super organized, and everything is planned right down to the smallest detail, when it's going to be made, how it's going to be presented. Because you're dealing with a material that's already in people's mind, not necessarily a classic art material. It's not paint, even though I use paint, but I think people are going to be a lot more ready to criticize, so I've got to get it spot on.

Is felt forgiving, or is it a difficult material to work with?

Maybe not to other people, but I think it’s really forgiving because I've been using it for so long. I don't know if you know much about sewing but it's not like making clothes. It's the easiest fabric to work with. That's why they give it to kids to make stuff, because it's so, so easy. You can glue it.

But felt is also a material that’s not associated with the kinds of things you're making. When you first started your art career, there had to be a moment you said, "Okay, I'm going to introduce felt to the fine art world."

To be honest, and I know this sounds crazy, but I never thought, or ever dreamed possible, that the fine art world would accept what I was making. I already had it in my mind that people would dismiss it as silly and childlike, and knew that I had a massive stumbling block to get over. When it was accepted quite early on, I was like, "Oh wow, shit just got real. I need to do this in a very, very careful way." I never thought that it would be accepted, but now that it is, I'm just like, "Oh my God, I've got this huge responsibility on my hands. Not only am I carrying this subject, I'm carrying this material into realms where it hasn't been before. I've got to present it in a way that continues to be challenging and lives up to the massive history of painting.” That's a huge responsibility. There are plenty of art critics out there who still won't accept that if you don't do the art yourself, you're not a real artist. I've been told a couple of times I'm not a real artist, and it's like, who the hell is?

I think the fact is that sewing is the equivalent of trying to do cooking as art, because it's got a function, because it makes everyday things like clothes. It's a craft, almost like manual labor, which makes it so difficult to pass off as anything that is technical or difficult. It actually is really quite hard to sew, although the thought is, "It's easy. People do it all the time."

I feel we should introduce your past installations to our American audience. Was the Cornershop in London the first big project? How did it go from you working in this form to aiming to do an entire store?

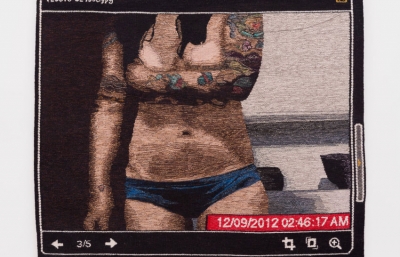

I had been doing group shows, so my pieces were getting seen. I'd made a couple of felt porn mags, all single items, one-off originals, stuff that didn't really have any meaning behind it. I just had an idea and I'm like, "That will be cool made out of felt. I'll make that, and I'll put it into this group show." No grand plan. I wasn't selling a great deal. I wasn't getting anywhere.

It occurred to me that in order to get people to sit up and listen, you need to do something that people cannot ignore. I thought, "What is the most eye-catching and voluminous thing you could do? So you shock people with the amount and quality of work, and the idea, no?" In other words, you create a spectacle, and that was what the Cornershop was. A normal neighborhood store, where every object was made of felt. I didn't realize how much of a spectacle it would be.

One funny anecdote you told me about kind of goes back to people asking for soda at our newsstand. You had people coming into the store who, out of the unthinking routines of their own lives, would walk in, try to buy something, and not even realize it was an art show. Or that the objects were made of felt!

That was the one thing that surprised me that was so wonderful about Cornershop, that it took on an entirely different meaning and life of its own that was so unprecedented. It was the power of a design product. It doesn't even need to be the same size, and someone will think it's real. Nothing of what I make looks that realistic. If you put them next to each other, it doesn't. If you make it in mass and put it in the right setting, people are so sleepwalking in their own lives that they don't see the difference, and that was what was so wonderful coming out of Cornershop. I never expected that.

It’s also the power of branding.

Huge, absolutely huge power of branding. On a very basic level, it was almost like a big joke, like a big practical joke played on commuters and people who are not paying attention, but actually ended up coming out as a stark realization of what’s incredibly true. Everyone is sleepwalking.

Were people in that mode and then realized, "Oh shit," and bought something anyway?

Yes. There were quite a few people who came in, looked around, walked out, and then came back in again and were like, "What the fuck?" There were a few people that were really, really angry as well. They thought that it was a hidden camera thing and the joke was really on them. Yeah, I guess it was, in a way.

I'm trying not to ask this question, because it is the question you get in every interview: how many items go into something like this?

People love to know numbers. I just get it out in the open. "Welcome to the Cornershop. There's 4,000 items in here. I made them all by myself. It took eight months. Next question, please."

I'm more interested in the actual act of time, that perseverance and practice idea we talked about earlier.

I also get, “Where did you buy your felt?”

That's was next question. No, seriously, your next big project was the Sex Shop in London’s Soho, so by the time you moved onto this, you had made a name for yourself. I assume that kind of performance project had to be a little bit different?

It did. I was a lot more aware of what I was doing. For about a year after, the Cornershop people were like, "Are you going to sell some more food? Are you going to make some more tins of soup?" I think it was really important to get away and be like, "No, fuck your tins of soup. You're getting dildos.” I want to be someone who creates installations and moments in time, and these weird capsules of life

Did you tell me that there is recycled material in felt?

Yeah, bits and pieces. It depends what stuff you get. I get acrylic, which is more plastic-based stuff, rather than wool. Actually, that's a really funny thing. With the Cornershop, I got a lot of real craft nerds coming in who were asking, "Do you make your own wool?" If you don't, they proper look down at you, like, "Oh, I make my own wool." You're like, "Fucking don't give a shit. Where's your fucking shop?" There's this weird hierarchy, exactly the same as there is in the street art world, the art world, anything like that. It's just in tiny minute sections of whatever you're doing.

There's a craft mafia?

Oh my God, yes. I read one review of Cornershop and they were like, "I went there, and to be honest, I was very disappointed with the tidiness of the stitching." I was like, "You are here for the wrong reasons." It's overcoming that sanctity about craft which, to be honest, I don't give a shit about... What I do is art and will never be anything else. Whether it's tidy or not... You wouldn't go up to van Gogh and be like, "You could have done it neater."

You know what's interesting in this is the expectation of what you should be doing because so much craftwork is about looking like it wasn't actually created by a hand. Whereas you're trying to actually show that it was made by hand.

They're like, "Big stitches, it's not very tidy." I'm not making a wedding dress. With any kind of craft, especially sewing, to be neat is to be the best, and it's the optimum thing that you're aiming for. It's like you're pissing them off and you're confusing the art world. No one really knows where you sit. For some reason, you get grouped in some street art thing. I don't know where that came from.

Okay, back from the tangent: Having the Sex Shop in the middle of London, in SoHo, changes the audience a little bit.

Huge. I told you the place next door was an actual brothel upstairs, and quite often they'd come into the doorway of the felt sex shop. You could always tell where they wanted to be because, for some reason, they'd be wearing a raincoat and carrying a plastic bag. Those were the people that were going to go and see the prostitutes: raincoat, plastic bag. The girls working there came down to see the sex shop and they really loved it. That was as much of an accolade than anyone else coming in there, really.

There was this girl who came in and said, "I'm looking for a vibrator." Totally serious. I was like, "Right." She was like, "Is it in the boxes?" I'm like, "Yeah, try and open the box." The box doesn't open, it's not real. She's there trying to pull apart the felt. I'm like, "Seriously? Are you on drugs? At what point did you not realize that everything in here is a cuddly toy?" After a couple of days, you were able to divide the people that you knew were there for the installation, and the people that were not.

In London, you could stumble into the Sex Shop, but when you recently did the Sex Shop in Montreal at Station 16 Gallery, there was no stumbling upon it because it was in a gallery. It completely changes the experience when you visit the work in a gallery, as opposed to your own installation. It serves what you're talking about in the fact that you are doing art. For every pop up, there’s an experiential installation that takes time, and, when it's in the gallery, it reminds people that the process is fine art.

Yes. I think it's really important I do both. Primarily, the most important thing will always be the installations, and that is the root of everything I've always done, and that will never stop—offering people a different view. They might not actually come to the installation, because it is quite imposing, and quite often they don't last more than a week. The Cornershop was a real rarity in it lasting for a month. The Gun Shop and the Sex Shop only lasted ten days. The New York convenience store in 2017, hopefully, fingers crossed, will be three weeks.

You clearly use your material of choice. What else do you personally like?

I like so much more about sculpture than paintings. I hadn’t realized this, but when I went to a print fair, the only single thing that I liked there were these prints by Michael Craig Martin. I realized that his were prints of everyday objects, and so I like things. I don't get on very well with abstract stuff. It's not that I don't get it. I'm not stupid. I totally understand abstract stuff, and it's got its place, it absolutely does, but it doesn't resonate with me. I don't feel any kind of connection.

Sculpture, I think, is entirely different because it feels... I don't know, it's got more of a presence and I think it's more challenging. You know when you go into any kind of gallery, sculpture obviously doesn't sell as well as paintings, because people wonder, "How am I going to show it on my wall? How am I going to transport it from my shopping bag to my wall?" Sculpture is hard.

There's something about the way that sculptures exist in daily life, where often there is a communal viewing process in a public space, and this rarely happens with a painting outside of a museum.

I think that's it. The only thing that I liked were the drawings of things, and anything else I hated. I was like, "Wow, okay, I guess really, really, really do like objects. I like things."

Lucy Sparrow will open Shoplifting at Lawrence Alkin Gallery in London on November 11, 2016.

-----

Originally published in the November 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.