Sometimes you feel like you know a person. In a documentary about Laylah Ali, her secret world was revealed, a place where paint colors never cross-contaminate brushes and newspaper clippings are organized by folders stapled neatly to the wall.

In my mind, the artist was forever encapsulated in this environment. But that film was made a decade ago, and people change. For artists, the magic happens far outside the comfort zone, and Laylah Ali is often leaning up against the uncomfortable. With ever-shifting ensemble casts and scenarios, her stories evolve to reflect our time and ask all the right questions.

Kristin Farr: Do you have a sense of why you are so precise and methodical, or do you not consider yourself to be either of those things?

Laylah Ali: I have trained myself to be precise and methodical in the studio in certain ways. It did not come naturally. I am also a big slob. The paintings are precise, and my studio is quite messy, though I know where everything is, pretty much.

Do you try to remain outside of your comfort zone in your art practice?

I think the best place is for me to be is where comfort meets discomfort, with the advantage going to discomfort. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say where familiarity meets discomfort. There are certain advantages in having familiarity with materials and process but that can be a hiding place as well.

Photo by Todd Mazer

How were you encouraged as a young artist growing up in Buffalo, NY? Did you spend time at the Albright-Knox Gallery?

I had a great elementary school art teacher who had a perfect art teacher name: Ms. St. Pierre. And my family went with some regularity to the Albright-Knox Gallery when I was a kid. I think that museum was important for me. I particularly remember a Pollock painting and the Samaras mirrored room installation that could be entered after taking off one’s shoes.

When I was older, a teenager, I would stop at the Albright Knox museum when walking a long distance in the Buffalo winter. It would be a chance to warm up my freezing feet and step in to look at the Jasper Johns number work they owned—it was close to the entrance door so it was easy to warm up and look around that part of the museum and then leave again eight minutes later to continue my trek.

More than any single work, I really loved that the museum was free. It set up an entirely different relationship to it than I would have had if we had to pay. We could not afford to pay to go the museum on a regular basis. I felt like I had a right to visit the museum, that there was no barrier in walking through the door. There was no pressure to take everything in at one time. It was a relationship that I had with that museum for around 16 years. Over time, I gained a sense of familiarity with it. Perhaps even ownership.

Photo by Todd Mazer

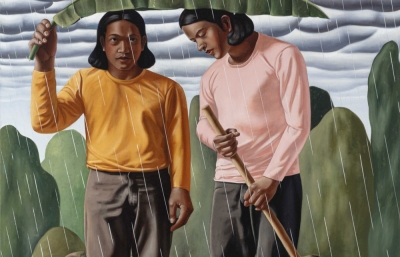

You’ve made paintings about dodgeball—such a cruel game. Talk about why it’s symbolic of the issues you consider.

Ah, dodgeball. It is impossible to move to the symbolic when dodgeball is steeped in physical reality for me. My memories of dodgeball concern one Tom Wolf—that was really his name—a self-appointed and rather dedicated child racist, whose unofficial job was to enforce racial segregation in our school. We seemed to play dodgeball all the time in my white, working-class, public elementary school. Tom Wolf was rather obsessed with degrading me at every possible turn, and dodgeball was a legitimate, school-sanctioned target practice on the only black person in the entire school. Abraham Lincoln Elementary School, by the way. Everything about this story is so perfectly named and all true. So I dodged and dodged because I did not want him to win, but it would have also been easier to have been hit by the ball to just get out of the game. I think I will let others derive the symbolism from that story. Some things in my work are not symbolic, they are just felt.

Is there a performative aspect to your work? Do you feel like you’re directing a scene when you create a composition?

Definitely performative. The paintings can be like crude stages or sets, the figures like characters in a play. I think of them equally as characters and figures.

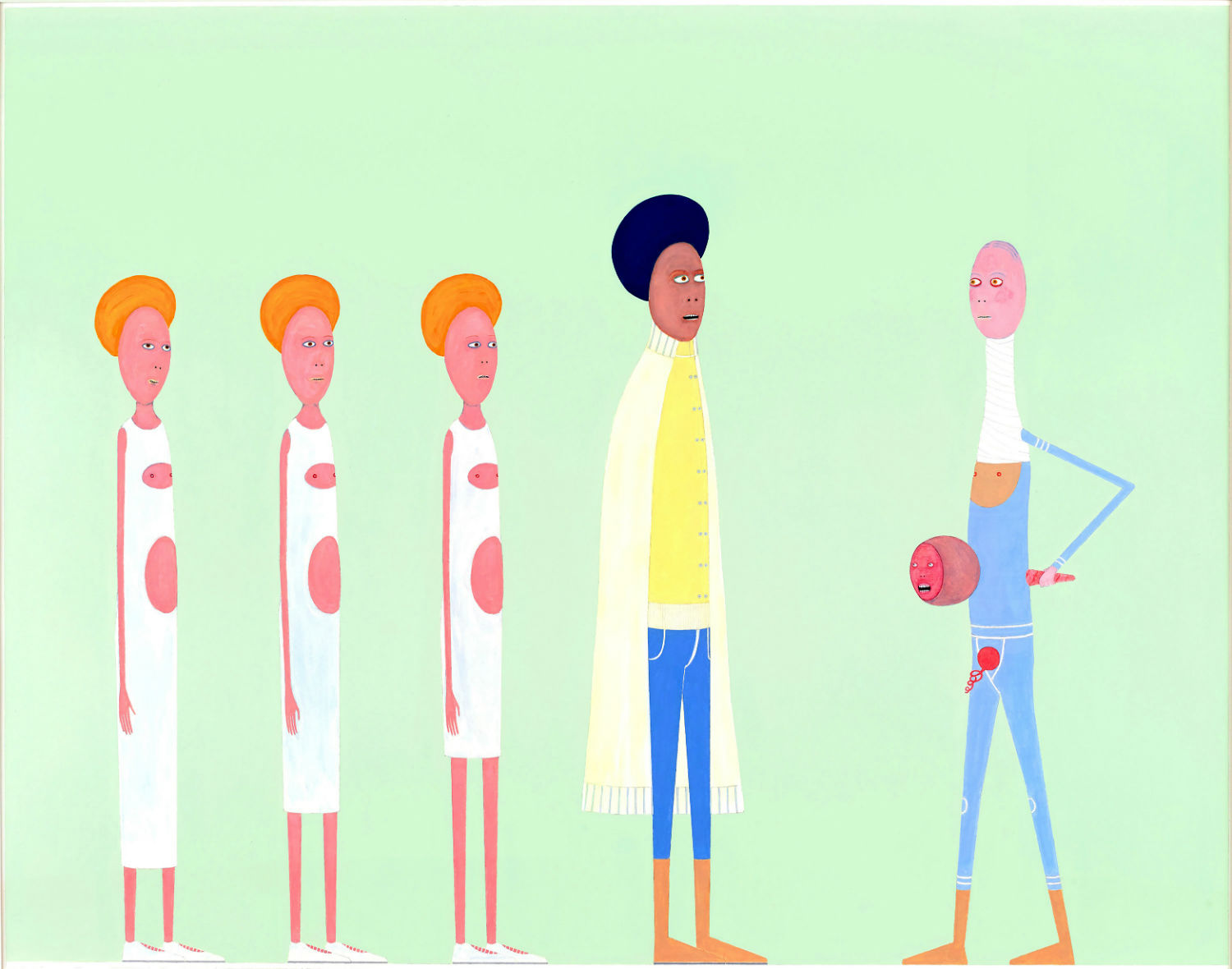

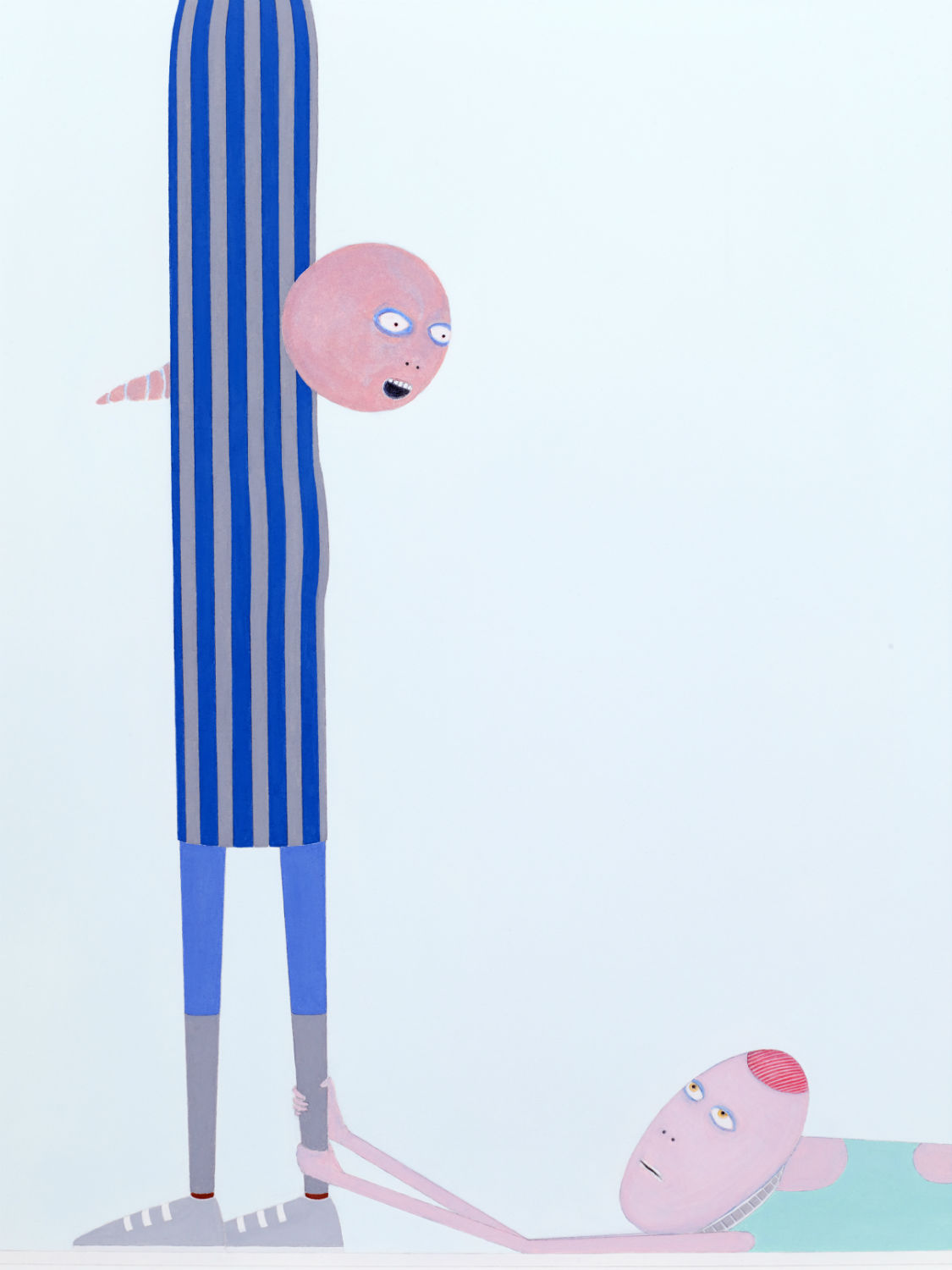

Tell me about the new Acephalous series.

These figures are gender conscious, as well as potentially sexual or sexualized. There is actual racial difference amongst the characters. There is hair. Some do not have heads at all, but they are still functioning, thus the title, Acephalous. They are on an endless, determined trek, a multi-part journey. It has elements of a forced migration.

Photo by Todd Mazer

You’ve talked about a notion that racism could be attributed to visual phenomena. Can you say more about that?

That’s one of those things I once said that was only partially developed and needed more context. Obviously, racism is complicated and deeply entrenched in ways that defy optics as well as being influenced by the visual. But given that everything today is being tagged with DNA influences, I would not be surprised that we locate something in our biology that has sway over the “us versus them” impulse. They probably have already found it and given it a name. Why is this impulse more pronounced in some people more than others? Is it really all caused by context?

Does your work change as awareness of horrific injustice increases? Have you referenced any specific stories covered in the media in recent years?

We might be aware of singular injustices as they are brought to our attention but we are still remarkably bad at understanding how everything is linked, how the patterns add up and convey larger meanings. I am probably more concerned with patterns of behavior than I am with singular events. Climate change has become an interest that is starting to lap at the edges of my work.

----

Read the full interview in the March, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz, on sale here.