Americans have been hungry for the West since restless souls dreamed of taking off over the Appalachians, armed with only a rifle and compass. They’re known as pioneers and went to war with a faraway king, partly for the freedom to feed that hunger, an insatiable, violent appetite that would later be glorified as Manifest Destiny. “The American people,” wrote French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville in 1835, “sees itself advance across the wilderness, draining swamps, straightening rivers, peopling the solitude, and subduing nature.” Just over a decade after that observation, it appeared that gold flowed through the West’s veins. Rivers bled, mountains leveled, and native peoples were exterminated. Setting foot on the rich soil could turn a poor man into a king. The women and children would be summoned when the time was right.

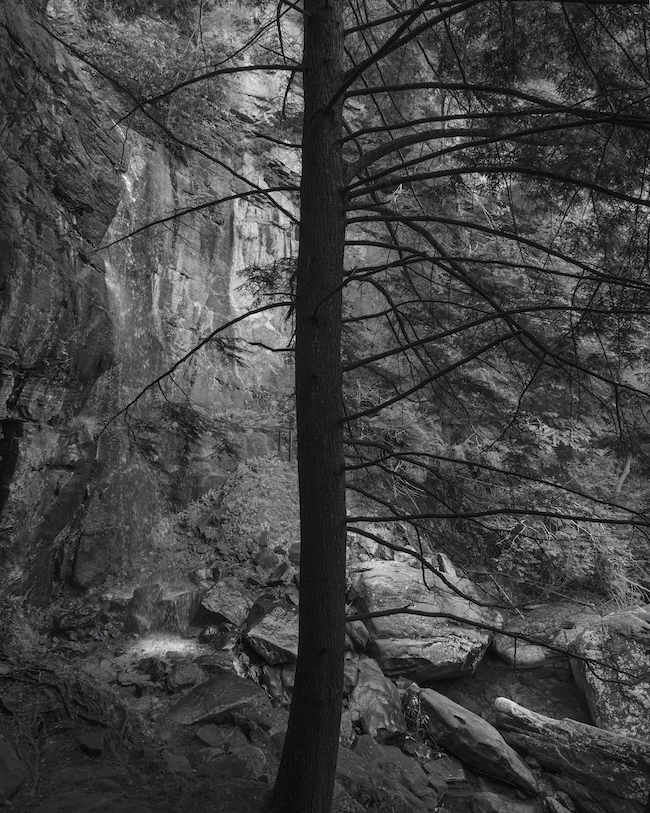

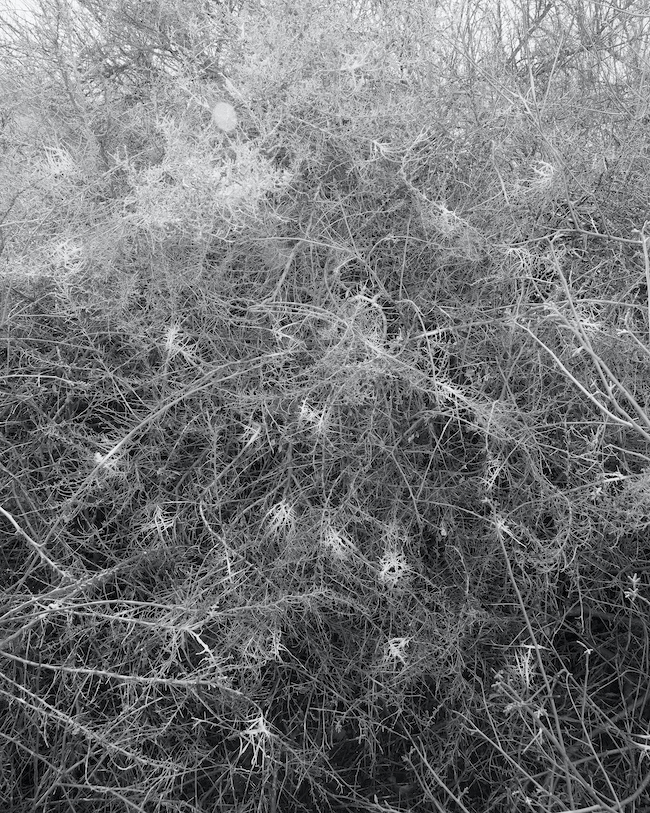

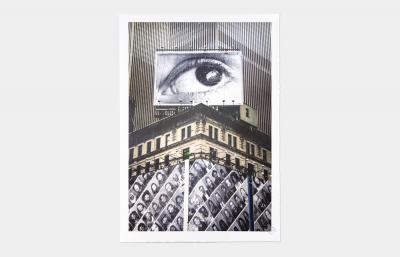

The images and stories from the early days of the American West remain alive in our cultural imagination as the confrontation between nature and civilization escalates in many iterations. Environmental historian William Cronon argues that the very concept of nature is illusory. It “cleaves the planet in two,” he says, “presuming that there is a natural world over here and a human world over there.” That division was clearly evident to Kristine Potter as she made regular trips between her home in Brooklyn and the western slopes of Colorado to photograph men hard-scrabbling across its rugged terrain for her book, Manifest. “[It] did not seem illusory. It was very real,” she insisted. It particularly struck her how much the landscape stood in direct contrast to the twentieth-century vista-view survey pictures that she knew so well. “My experience felt much more immediate, more disorienting and, I think, less grandiose.” As Potter’s head and lungs fought to find their footing in the high mountain air, an operating question became, “Could I make pictures of the landscape that reflect this feeling?”

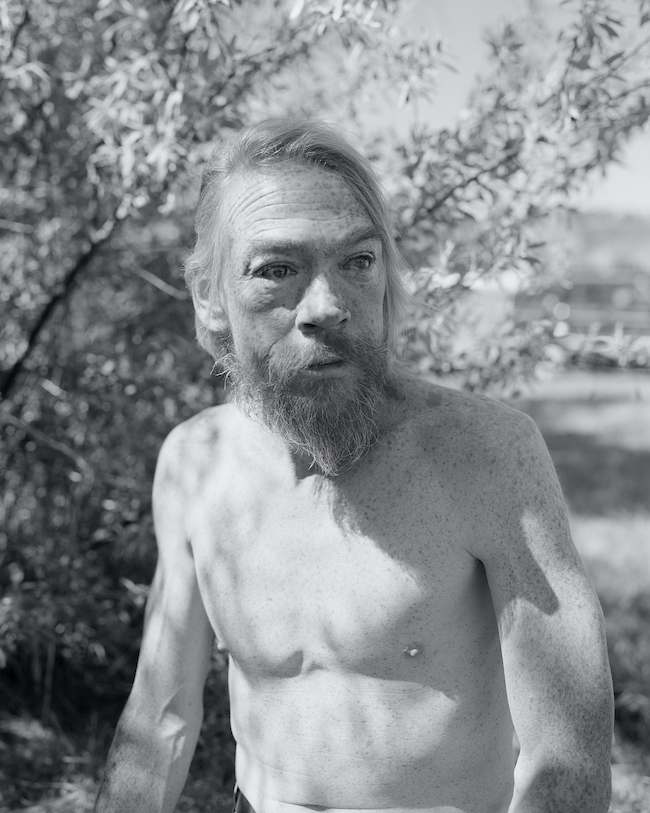

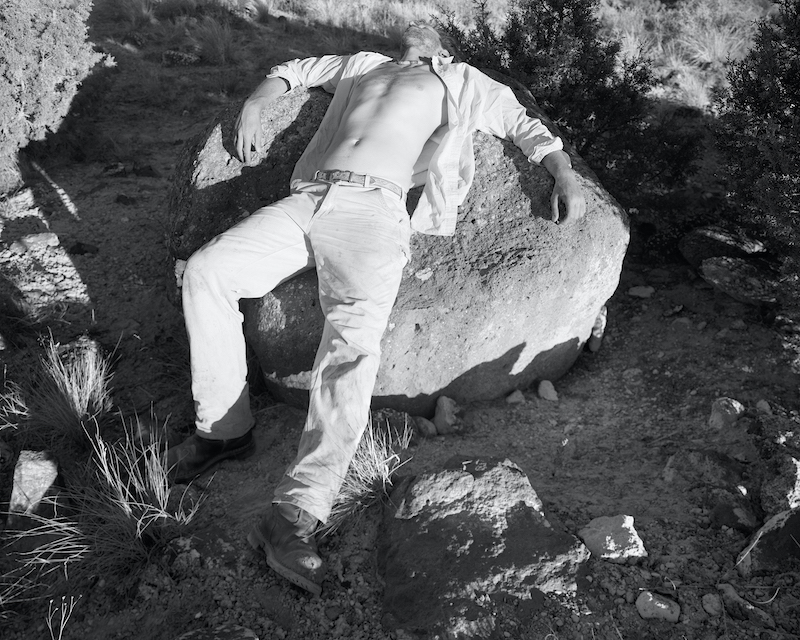

The people in the pictures she did make, “Were, of course, habituated to the environment,” she explains. “I think they have tremendous respect for the insistence of the landscape. It’s not easy to manipulate, and it’s what keeps the area so remote. For some people, that’s an escape from civilization.” Prior to Colorado, Potter spent time at West Point working on The Gray Line, a series contemplating masculinity and the American Soldier. Men living in isolated areas of the American West presented an opportunity to shift her lens to another archetype of masculinity. The American cowboy typically dominates a mythic landscape somewhere between civilization and the wild, not quite belonging, yet inextricably tethered. Potter flips the perspective, bringing a feminine gaze and energy that results in a more honest, reciprocal portrayal of the men and the land they inhabit. “I’m not attempting to reinterpret how they see themselves,” she says, “I’m generally after a reinterpretation of the cultural expectation.”

Now based in Nashville, Potter has directed her attention towards violence within the folklore of the Southeast, and how scrupulously linked bodies of water are to those stories. “I’m interested in how the landscape seems capable of holding and echoing the memory of its past.” Much like Manifest, the new series, Dark Waters, investigates this feedback loop between nature and myth, finding parallels between expressions of portraiture and those of the land. Sensitive to the past, Potter’s work is engaged with the present. Acknowledging darkness, destruction and violence, her photographs are free to reflect the beauty and emotion in each image. —Alex Nicholson

“The studio portraits of women are responses to the history of murder ballads that come from the region. Many of those songs recount the murder of a woman at the hands of a man, whose body is left submerged in water. I think of them like… lifting those women from their fate and reanimating them.” —Kristine Potter

“I do discuss my intentions with subjects. Most often, I’m really trying to establish that I’m not a journalist, but a storyteller, an artist. Because I work with a large format view camera, there is a lot of time built around the setup and adjustments needed to make a single picture. I fill that with conversation and I ask a lot of questions.” —KP

“I brought ways of making portraits to the landscapes. I’m much closer, my proximity is more dangerous, and I’m interested in complex ‘expressions’ of the landscape. Once I realized that making those kinds of pictures was a new and interesting endeavor for me, I started taking these long hikes with a DSLR so that I could better manage the terrain. The idea was that I would come back with my view camera if I found anything good. But I got back to my studio and discovered that those pictures were already good, in my estimation, and held some surprising ideas—probably because of how loose I was when taking them. I didn’t need to go back. So that’s when a hybridized picture-making strategy evolved for me. I’d choose the right tool for the right situation.” —KP

Supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Grand Prix Images Vevey award, Dark Waters will debut in a solo show in Switzerland this fall. Manifest is published by T.B.W. Books.