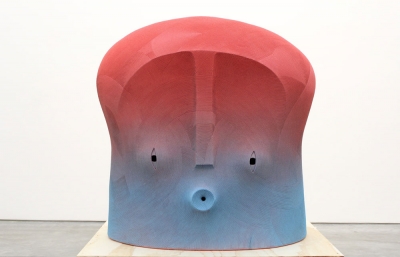

San Francisco-based sculptor Jud Bergeron is a storyteller. Classically and formally trained, he navigates the channels of life, death, love and loss, using his own object-based language to inform and connect with an audience through a unique perspective. Cleaving his love of all things metallic, a softer side has presented itself, integrating digital technique to further expand his expression of spatial orientation, allowing ephemeral materials to help build the blueprint for a new series of geometric possibilities.

However, the use of technology in his process does not provide a shorter path to the end result. On the contrary, Bergeron uses these tools to augment potential, not to abbreviate the labor. This enables a fractal expansion for each piece, each modification determining the next, like watching a snowflake crystalize in slow motion. Fascination with natural phenomena integrated with the departure of traditional anatomical elements presents a new visual discourse, ripe with possibility.

Read this feature and more in the January 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Gabe Scott: In the last five years, you’ve leapt into some very different creative territory: a greater interest in the abstract, as opposed to figurative, a shift from metallic and earth tones to the vibrant, and a willingness to embrace permeable mediums such as fiber-based materials. What factors in your practice prompted such a bold change?

Jud Bergeron: My work has always changed radically with each show I do. It’s hyper-narrative and self-reflecting in nature. One of the games I play with myself is always asking the question, “How can I tell a story using only objects?” Part of the narrative has always been the choosing of materials to help drive the story. For 16 years, bronze was the material most available to me and I worked at foundries all over the country. I became so reliant on that medium that I felt burnt-out, but things changed when I moved to New York City in 2006. Bronze became less available and too expensive, so I started experimenting with other materials, and my work evolved in a huge way.

In 2008, I had a solo show, I Will Wait Quietly, at Sloan Fine Art in New York. That show dealt with the death of my childhood friend from a heroin overdose. His name was Bill Reynolds and he was an amazing poet. The challenge was to create a sculpture that dealt with his life in letters, as well as his death and my relationship to both. I chose to create works using only text and only materials that were black or white, such as steel and wood, like the written word. The show was a blend of abstract and figurative works that were all created by using a single material in a direct manner to make the statement.

In December 2008, my son, Fletcher, was born, and two years later, my daughter, Storey. I began to examine life as a parent and that led me to my next solo show in 2013 in San Francisco at Mark Wolfe Contemporary, Becoming. Being a parent to little kids is fucking insane, filled with joy and tears and lots of multicolored items that hurt when you step on them. It’s also full of fear and anxiety, and I wanted to represent that. In choosing cast resins and bright automotive paints, I made nuclear explosions out of rubber duckies, piles of candy-colored abstract babies, and brightly colored wall works of floating ceramic candies.

In 2011, we moved back to San Francisco, and I began again to take a long look at psychedelics, which has led to a more fractal path in my work. I began working in paper. It was direct, quiet and contemplative and there was no pressure, monetarily or otherwise. If it didn’t work, I could throw it away and the only thing I lost was time. Either way, I would make huge creative gains with each piece. I began to develop a process of mixing current technology and bronze casting so that paper pieces were realized into permanent sculpture. That all culminated in 2016 with two solo shows From Analog to Digital and Back at K. Imperial Fine Art and A Collection of Objects at Carneal Simmons Contemporary Art in Dallas, Texas.

How would you trace the evolution of your practice from the austere use of metals and human anatomy to the application of scientific knowledge and less permanent materials?

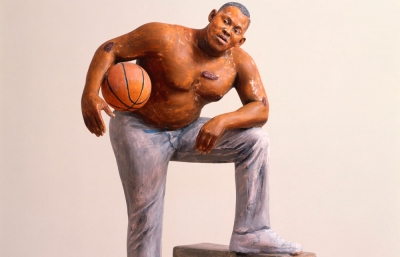

I trained classically at The Old Lyme Academy of Fine Art in Connecticut, where my 80-year-old teacher was one of Bordelle’s students. For two and a half years, I studied only the figure. My classes were eight hours a day sculpting the figure, portrait or bas-relief, and we were required to have an encyclopedic knowledge of anatomy. It was all I knew. When I left, I began working at foundries, first in Santa Fe, then in Boston, and finally, in Berkeley, where I got to work with Peter Voulkos, Stephen DeSteabler, Nathan Oliveria and Ruth Asawa, to name a few. Seeing how DeStaebler approached the figure, heroic and dystopian, visceral and beautifully ugly, was a revelation My mind was blown and I began to create figurative works that eliminated anatomy and were loose and direct and raw, and they began to incorporate architectural elements. That was where I broke free from my traditional training and started to see.

Then 3D printing came along and people kept asking if I thought it would render the sculptor irrelevant. I thought just the opposite and became inspired. I saw a huge opportunity to create multiples, scale existing works, and use it as one more tool in my kit. I can work out my patterns in paper, refine them on the computer and print them, or have them carved in foam to monumental size. It’s pretty incredible what you can do these days, and a number of artists are working with these tools. Check out my friend Mars-1’s molecule project, really cool stuff.

At some point, do you see an intersection of the future and primitive? Have you developed any kind of digital dalliance with computer-based processes?

I guess I see that in my current work. Some of the paper pieces have a very figurative feel and the process of going from analog (paper) to digital (3D scanning and printing) and back to analog (bronze casting) touches on all the various methodologies at my disposal. As the price starts to come down on 3D printing, I can see being able to print directly in bronze at a monumental scale and virtually eliminating the foundry process, which will be a major game changer.

In terms of technology-based processes, if I’m honest, none. I still toil away in my studio the old-fashioned way. The big difference now is there are more toys in the sandbox and a bunch of experts that I trust to help me get my vision across. I work with my high school friend, game developer Rich Larm, to create all my 3D models. We work really well as a team. I use Metalphysics Foundry in Tucson to further develop the projects. They get the 3D prints made, refine them, and ultimately cast them in bronze. Those guys are amazing and I highly recommend them to all artists.

Can you explain the process of 3D printing directly in bronze? How do you feel about virtually eliminating the foundry process? Is there a level of romance that gets lost in terms of general interaction with the materials?

You can print in metals now, and the process involves a vat of gel filled with particles of either stainless steel or bronze. Lasers will focus on points within the gel, solidify the particles and build the model, which is pretty rad stuff. That being said, I've never done it. My hesitation with that process is that you remove the hand completely. Once you lose the hand, then everything starts to feel a little bit cold and lifeless, which is the beauty of bronze casting. You can employ some of these 3D techniques in concert with traditional methods.

Then what's the difference, and is that a fair question?

I feel like we will lose something for sure, but I also feel like that's the way things are going and there is really no avoiding it. On the other hand, if you look at the potential of what you can do, consider a blur, for instance. When you blur your eyes, you see one thing, but when you ask a computer to blur something, it is entirely different. Being able to 3D-print a computer blur is something that was never possible before, and that’s exciting. I've got mixed feelings about it for sure.

In itself, does removal of the hand risk the integrity of the process?

It feels like we're moving more and more in that direction and there's plenty of artists who just design their work in a computer and skip the analog portion entirely. When working in analog, you're making all decisions in real time and in real space, and you're also making mistakes in real time and in real space. Sometimes those mistakes lend themselves to the end product and change a piece completely, whereas, in the computer, you can make all the mistakes you want and there are no repercussions. You can do a thousand iterations of a piece and lose track of where the soul is.

Then is it more about creating a perfect object or is it the physical and interactive journey to reach the appropriate conclusion in each piece?

I love the process of refining something until I can make it the most perfect example of itself, but I also like the involvement of chance.

How do you think the application of those processes affects the more classic elements of sculpture like mass, shape, volume, gravity and color?

On the one hand, you can work out all of those tenants in the computer, so you're spending time but not necessarily money making mistakes. That's a really nice shorthand for sculpture and it's a helpful tool. But on the other hand, it makes creating sculpture so easy for every Tom, Dick and Harry who might not have a good eye for form, ending up with a bunch of shit in the world that is clunky and dumb and not formal.

Does that then also present more of a positive process of illumination for the people who naturally do have a feel for form and those who don't, an instance where natural selection comes into play?

I guess, but as we all know, there are plenty of people who have terrible taste.

Have you developed more of a fascination with possibility and less with the known, at least in terms of geometric abstraction?

There is never a “known” with the geometric works. I begin with a single shape and build from there. Each edge informs the next shape. It’s like building a puzzle in space with no box top for reference. The whole time, I’m trying to push the boundaries while still maintaining a formal sculptural quality. Occasionally there will be outside constraints, like in the case of the Crystalline Baby, where I had the chair and I needed to build the form to fit that space. But, in general, the process of creating the abstract pieces is a pure stream-of-consciousness endeavor.

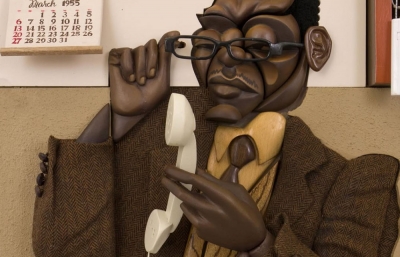

There’s no doubt your formative years were probably informed by your work with Ralph Steadman. Being lucky enough to collaborate with him a couple years ago on a bronze sculpture of his iconic Vintage Doctor Gonzo drawing, what was it like working with a personal hero? How did the partnership come about, and what were some favorite experiences or takeaways?

It came about through my good buddy Brian Chambers, who is a collector and an art dealer. He called one day and and asked, “What if I can get Ralph Steadman to collaborate on something with you, would you be interested in it?” Of course I jumped at the chance! Weeks went by, and the next thing I knew, I was working with Ralph! Seeing an email in my inbox from Ralph was one of the happiest moments of my life. I still don’t know how Brian did it because there is nothing on my website to suggest that I could pull off a figurative piece like that, but he did. The guy is a wizard like that!

Both Steadman and DeStaebler hold a similar place for me in how they approach the figure in a raw, visceral way. My friend Rich Larm once said that Steadman taught him that there could be anger in a line. I always liked that.

With your work focused more heavily on a figurative and human element, particularly within the bronze work and casts, has the Steadman piece been the most definitively figurative piece thus far?

Yeah, definitely. He took a leap working with me, and we collaborated beautifully. I would sculpt, send him pictures and video, and he would send me back a funny poem or some crazy rant. In some strange way, this felt approving and encouraging. When we finally got on the phone, he imparted valuable knowledge when he said, “All the information is in the drawing,” and I thought, “Ha! he's absolutely right.” So I went back to the drawing and back to the drawing until I got it right. I think we are both really happy with the result. We are starting to work on the next piece based on his drawing Bats over Barstow which was on the cover of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Working with him is a life’s joy, and I love his family so much. They are salt-of-the-earth folks.

That project must have certainly been conducive to rekindling the occasional psychedelic tryst. How has that affected the optics and perceptions of your production?

I have a long history with psychedelics. From age 13 to 19, I followed The Grateful Dead all over the country, I went to something like 65 shows. It was an amazing experience, and sadly, one that I don’t think my kids will ever have. It was a relatively safe place to expand your mind and I certainly took advantage of the opportunities to do so. Then real life hit, and my generation got angry and complacent, and for me, that magic was lost for a while. I decided to explore that part of life again after my daughter was born. It’s been so interesting to approach those experiences from an adult perspective, rather than of a teenager who just wanted to get high. I feel like it has given me the gift of being open to new ways of seeing and not being so rigid in my practice. Plus, it’s damn fun!

What do we have to look forward to from you as we close in on 2017?

I’ve got a couple of huge commissions in the works that I can’t really talk about just yet. I’ll be showing at Context Art Miami with K. Imperial Fine Art and at SCOPE Miami with Alexander Chambers Gallery this year during Art Basel Miami, and I’ve got a solo show scheduled for September 2017 at Cordesa Fine Art in LA.

----

Originally published in the January 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.