Doug and I first met John Fekner back in 2018, when the three of us were attending the Nuart Festival in the city of Stavanger, Norway. John's unassuming presence conveyed an aura of calm amidst the sea of chaos swirling around him. At that point, I wasn't fully aware of his artistic legacy, and he certainly isn't the type of person who has the need to announce it. As a scene, street art and graffiti have no shortage of characters, with many whose presence demands attention by way of flamboyant or signature style choices. John's not the type of guy to be donning a trilby and sunglasses anytime soon.

To understand the significance of his ability to marry street and art culture, we have to go right back to the 1960s and the 1970s, to a time that predates Banksy, Blek le Rat, or even Basquiat. John was a young art school kid with a penchant for social discourse and a love of the concrete playground that was New York City. Like all great artists, John's work is a reflection of his surroundings, in his case, a flower pushing through the rubble of a city pressed to the limits, a product of his environment.

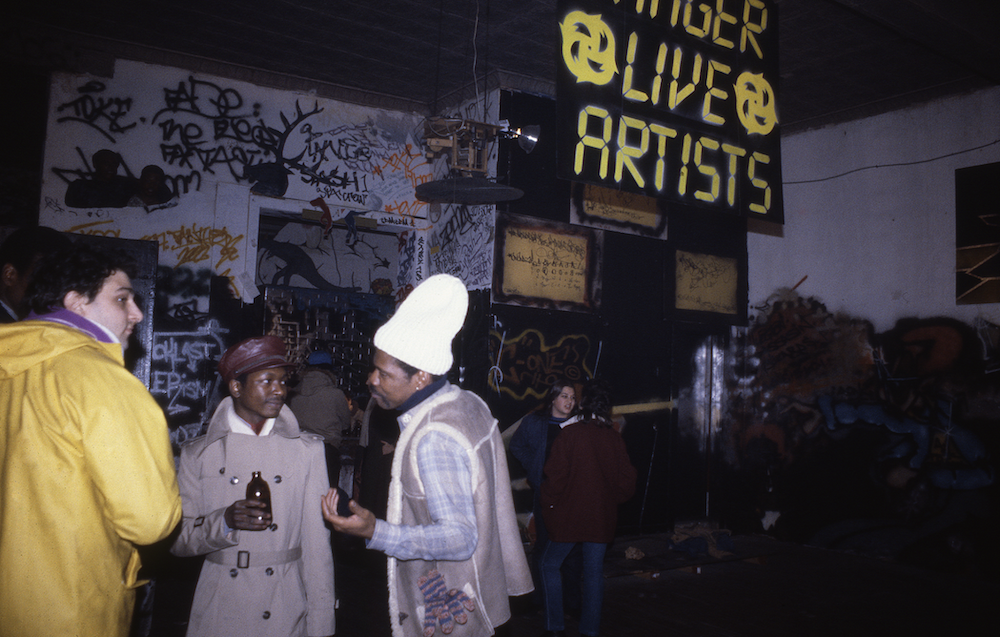

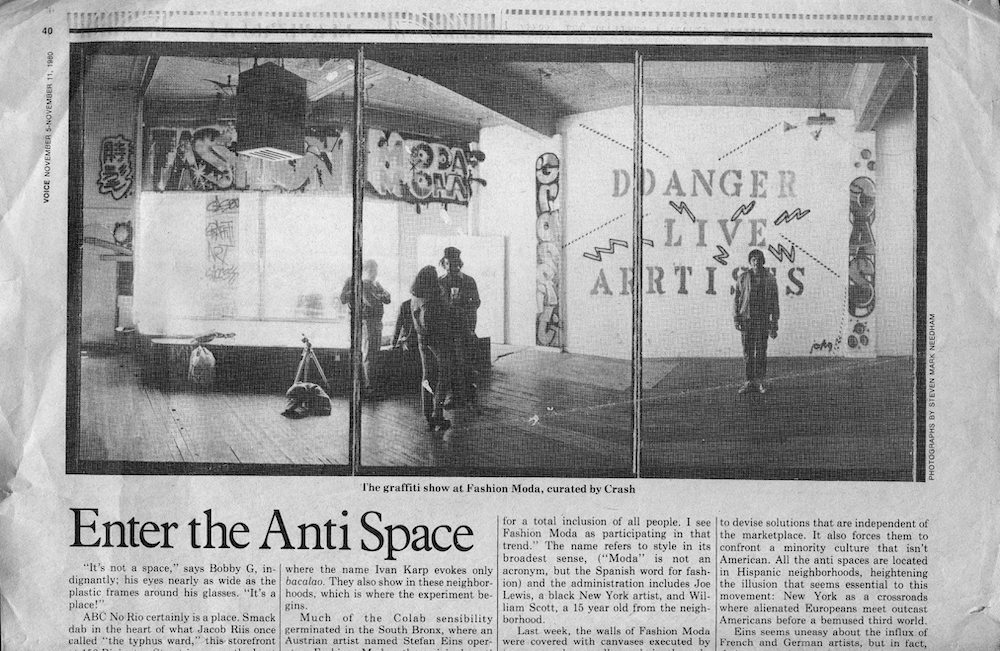

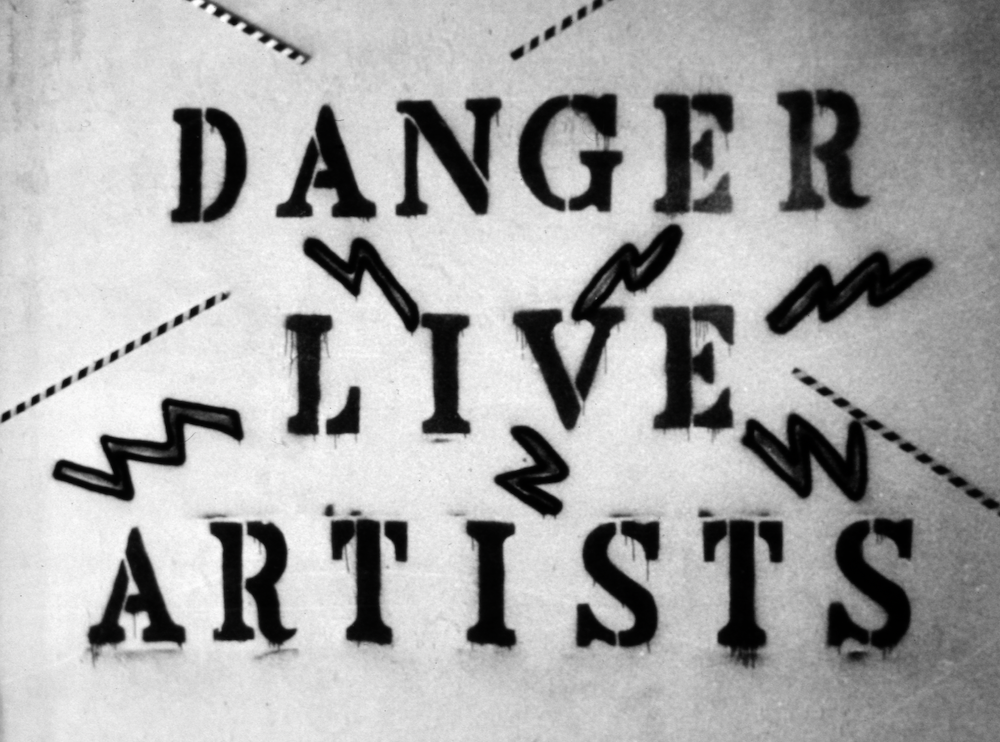

The work is legendary: stenciled text that boldly proclaimed “Broken Promises,” “Urban Decay,” collaborations with the original Space Invader, Don Leicht, or his presence around the Fashion Moda space. In short, Fekner has been one of the most pivotal political and social voices in street art and graffiti. Through conceptual art, photography, music, poetry, stencils, paintings and even early forays into digital art, Fekner has always been at the precipice of prevailing art culture. Dough and I persuaded him to sit down for a chat — Evan Pricco

Evan Pricco: Throughout your career, and even now, with your almost slight discomfort in doing an interview, is such anonymity just a point of freedom for you?

John Fekner: I think so. It was a place where I could find some solace and something where I'm going to do what I'm going to do on Friday night. I'm not going to hang out with the kids down at the park where I lived. I would spend a Friday or Saturday night doing artwork. This is back into the late 1960s, into the '70s. And that was just built into me. I was kind of, like, I'm not going to say a recluse, but I needed the time when I could just do something. I would use my time that way. I thought it was productive. I mean, some people would read books, but it wasn't like being in the park every night and being a showman or playing handball or hockey; and then cards and doing everything associated with hanging out at the park in the middle of the night. That's where I first started doing outdoor work.

Doug Gillen: So let's talk about this outdoor work then. What was the motivation for you? I imagine there wasn't a huge amount of this kind of work around NYC in the late 1970s. If I'm a young street artist coming out now, it’s a very different time and I could easily be inspired by the never ending amount of street art that's out there, but what was it for you?

Well, there wasn't that much. I mean the first large text I did was a phrase from The Small Faces, and I wrote the words “Itchycoo Park.” It was a hit, and my friends and I decided to just juxtapose things. I took a green highway sign off the Grand Central Parkway. We brought it into the park and hung the highway sign on the metal fencing above the handball court walls. So it was like this incongruous thing about why this sign here would be pointing to the Grand Central Parkway exit. I was in college, and this was the fall of '68. We painted with white paint and rollers, and it was large. That was the first instance of doing something outside with large letters. And I then did a couple other things like bringing a car into the basketball courts. It wasn't a park, it was a playground, a cement asphalt playground. And that's why I'm such a physical wreck these days because I never played on anything that was soft or grassy or a football field. Everything was rocks or stones or asphalt.

Getting back to where that led, in terms of the stenciling, I was very fortunate to be involved with the early Soho scene in 1968. My teachers at the New York Institute of Technology founded the first co-op gallery called 55 Mercer on Mercer Street. And a few years later, Mercer Arts Center opened up and that was the first place most punk bands started to play. It was the early era.

EP: In 1968, when you took the train in New York City, were there already tags inside the subway cars?

No, I think it was pretty obscure, and probably pretty small. I mean, there were gang members that tagged the bridges, the Hell Gate Bridge, names like that coming out of West Side Story. If you see the original end credits, and even through the movie, there were some pretty interesting early… you might not say graffiti, but it was definitely somebody putting something on a wall in urban times. I'm not talking history here, I'm talking, like, the late 1950s. So there was some stuff around, and of course, Taki 183 was, like, everywhere.

This has me thinking about my own history. I had a teacher in art school in the late 1960s who told me a really great thing: you don't have to be an artist and use paint to make a painting. That was kind of profound, and I came in the next day and I made a painting with masking tape. He looked at me, like, this kid got what I just told him. Before then, I was doing landscapes and portraits, the usual college 101 foundation type of paintings, which was really great. So at the time, that sort of turned me onto a different type of approach and work. The second important thing a professor told me was that there's not just the real world and the art world, John. There are other worlds you can look at.

EP: What you're kind of explaining, and I know we hate using this term, but it's almost like you were kind of given access to becoming more of a conceptual artist.

I was. It was conceptual art. And that was the start of, like, Fashion Moda, breaking all the rules.

DG: I want to go right back into this sort of street sensibility. There's this other world, but what was your coming of age into art, the kind we look at, say, from the early 1960s. Was that an option?

No, we were looking earlier than that, as kids having different types of models, car models, building models, painting models, some type of casting wood burning kits. My parents always gave me those types of presents when I was, like, seven or eight years old, so I was already drawing. I was combining some types of drawing. I still had drawings with text, and, of course, like every artist, cartoons were very important. The Flash was my guy. I did a comic book with my friend, and we made a black and white zine when I was 14 years old. I was writing in 1965, poems and stuff. Then realizing as that went on, I thought. ‘why do I have to write a whole book or write a poem when I can just say exactly what I want in one sentence?’ You get that from Bob Dylan. I mean, it's just kind of like, yeah, ‘The Times, They are a Changing.’ I mean the song could just have been that, Or “Blowing in the Wind.” I thought that the efficiency of that type of approach was very interesting.

I applied to Pratt and Columbia University and was accepted, but my parents, who had never owned a house, always lived in an apartment, could only afford another school. It was a brand new school, the New York Institute of Technology, which was a lot cheaper than those two. I wound up going there, and it was the best thing that probably happened to me.

EP: Were you aware of how these people around you were going to define that period of time, folks like Jenny Holzer, Keith Haring, Basquiat? Were you aware of all this happening?

It felt very important because every day there was something new being brought to the table. A lot of it was driven by music, a lot of the rap, electro, hip-hop, whatever; I mean, everybody listened to Kraftwerk, I mean, hearing a song for 20 minutes driving from Jackson Heights to go to play West 4th Street handball, and the song was still on. It's phenomenal.

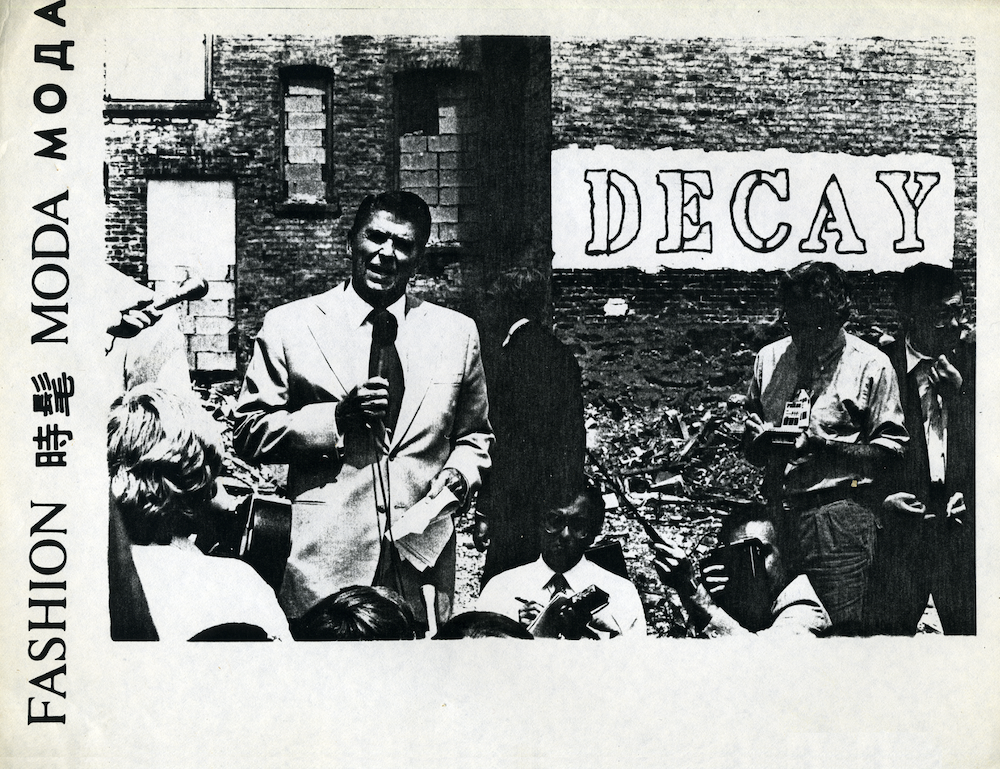

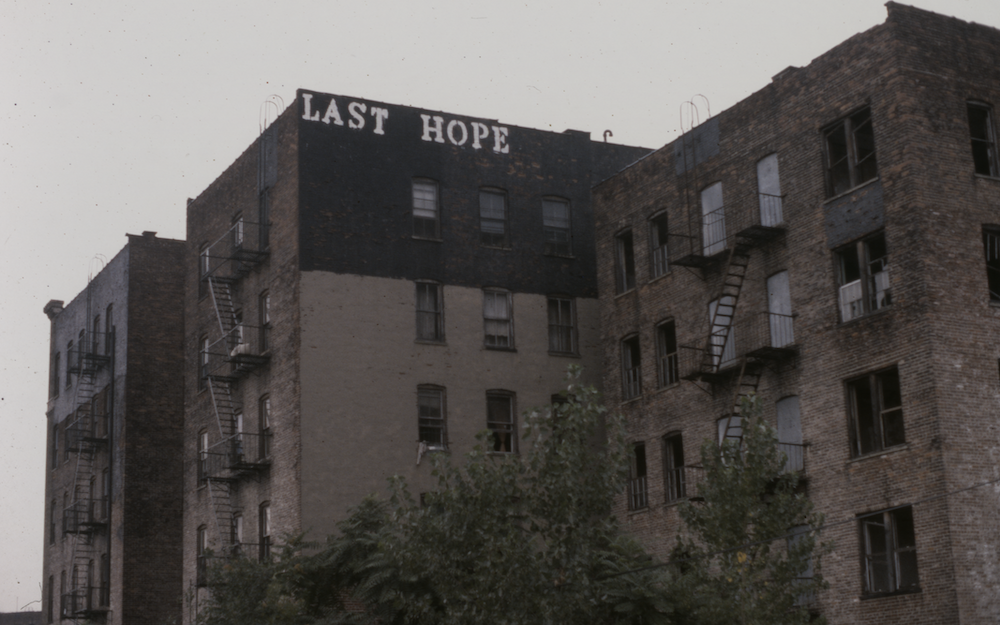

DG: Some of your most iconic images come from the 1980 series in the South Bronx, a city in the midst of a crack and heroin epidemic. There were staggering rates of homicide, burnt out and abandoned cars, piles of rubble and buildings that were more like vestiges of war than places of comfort, forming a concrete playground. To draw attention to the scale of the city's mismanagement and lack of investment, you and your long time creative partner, Don Leicht created a series of large scale, high impact stencils on buildings throughout the neighborhood. The simple, but effectively bold captions, red phrases like “broken promises,” or “decay,” gave the desolate buildings a life, as they cried out for attention and change. How did this come about?

The “Broken Promises” came from Jimmy Carter, who was President at the time. Ronald Reagan, a presidential candidate for that upcoming November, was in New York. So I didn't know what was particularly going to happen, but there was an alternative people's convention from people across the U.S. as well as the local people. Don taught on Tinton Avenue in the South Bronx, so we knew these neighborhoods. I was already doing stuff in the decaying areas in Brooklyn and parts of Queens. I knew that the Bronx was a place to do something, a place where this could really be big.

DG: So, let’s go smaller. I'm really interested in the history of the stencil. What did the stencil give you that writing something freehand didn't?

Authority. It gave me the look of authority. It looked official. It looked like it was done by the Department of Sanitation, something so big that it would catch your eye. I mean, they would tag a car, and if there was an abandoned car on a highway, they would put a little sticker. So I just took that idea and just made it on a construction wall. It would say “post no bills, post no bills.” I took that and made it “Post No Dreams.” That was a tribute to Don because an art gallery person told him that his work would never be shown on 57th Street. Don came out all depressed, and he was thinking that it was just not going to happen here. So I did a piece called “Post No Dreams” around the IBM building at 57th and Madison. I was always trying to make it look like maybe it was legal!

JohnFekner.com