It’s fairly certain that no one suggested to Jim Marshall to “be sure to wear some flowers in your hair.” As filmmaker Eric Christensen remembers, “Jim Marshall was many things: confrontational, sometimes kind and generous, other times irascible and politically incorrect, but above all, a great photographer who always somehow managed to get the shot he wanted.”

All photos © Jim Marshall Photography LLC

His legacy is aptly summed up on the front page of his official website with the defining maxim, “Cars, guns and cameras.” The order of importance is debatable, but, while not festooned in daisy chains, he could always be identified wearing an armament of photographic weapons, ready to shoot. The Summer of Love is legendary, and like any romance, fraught with frothy fiction and cold hard facts. —Gwynned Vitello

Read this feature and more in the March 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Jim Marshall’s 1967 at the San Francisco Art Commission Gallery at City Hall captures the whole social symphony. SFAC Director Meg Shiffler is the opening act, as she relates how the show came about.

Meg Shiffler: I wanted to create an exhibition at City Hall that would tie into the citywide celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love. The SFAC Gallery’s City Hall program is primarily devoted to photojournalism and fine art photography, and it came to my attention that San Francisco has never hosted a large-scale exhibition of Jim Marshall’s work. I called his longtime assistant, Amelia Davis, to discuss the possibility, and she agreed that Jim would have loved having a city-produced exhibition of his work inside the historic structure known as “The People’s Palace.” Jim was a regular guy, and the fact that the general public will have access to the show would have thrilled him.

The idea of the show was generated through a series of conversations between Amelia and me. How do you curate an exhibition of 89 works from thousands and thousands of images? We started by narrowing the show down to the photographs he took in one year, 1967. Then I thought it would be interesting to focus on Jim, and in order to do that, we would present the exhibition in chronological order, so the audience could follow Jim as he documented this pivotal year. He was an absolute beast of an artist—insatiable, really. The amount of work he produced was staggering, and viewers will leave with a better understanding of his role as a documentarian and his commitment to the musicians.

Janis in her apartment, 1967 © Jim Marshall Photography LLC

My favorite shots are the ones where you know he was given special access to the lives of his musician friends—the shots no one else would have been able to take. He and Janis Joplin had an incredible relationship, and at the very end of 1967, he took photos of her in her apartment. You can see how comfortable and trusting she is with him, which makes those photographs feel warm and private.

Media maven Eric Christensen just released the film Korla and was a contemporary of Marshall’s, smack in the heat of the action with some indelible memories.

Eric Christensen: He was early to arrive on the music scene in Greenwich Village, the jazz scene in Harlem, and then at the beginning of what would change San Francisco in the early 1960s. He took iconic shots of The Beatles at both the Cow Palace and at what turned out to be their final concert performance at Candlestick Park. He had carte blanche to shoot from the stage at the Avalon ballroom and at Bill Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium—or any other music venue, for that matter.

He was everywhere around the rock scene, and I wanted to be there too. Working as a kid after school for Autumn Records and Tempo Productions run by legendary underground disc jockey Tom Donahue, I managed to get on guest lists. Jim was always there, clad in blue jeans and his trademark corduroy coat, Leica cameras strung around his neck. Access was key, and it was Jim’s tenacity that always got him where he wanted to be. His work was his calling card. In the case of Miles Davis, who was notorious to work with, it was an iconic photo of jazz great John Coltrane that he gifted, so Miles let Jim do what he wanted. In one case, a trip to a boxing ring for a shot of Miles sitting by the ropes.

Eric Christenson with San Francisco DJs Tom Donohue, Rachel Donohue and Tony Pigg photographed by Jim Marshall backstage at the closing of the Fillmore in 1971.

I got to know Jim pretty well when I was a student at UC Berkeley. I went to a show in the winter of 1968 at the UC Greek Theater, and in hindsight, made the mistake of asking Jim for a ride back to San Francisco. The movie Bullitt had just come out, and Jim had just bought a brand new V8 Ford Mustang, much like one Steve McQueen raced through the streets of SF in the movie. In just 15 minutes, we were in the city, a trip that normally took at least half an hour. Jim put the pedal to the metal as I sat next to him in utter fear. The fearless aspect of his personality was never more apparent than at Bill Graham’s Day on the Green show in 1977 at the Oakland Coliseum. Peter Frampton had headlined two sold-out shows on July 2nd and 4th. I was producing and directing a three-camera film shoot from the side of the stage, right next to Jim, who got right in front of Frampton as he merged to take the stage. No one in their right mind would mess with Frampton’s managers, and they told Jim to back off. But Jim kept shooting, words were exchanged, and Jim told them, “Fuck off. I’ve got guns, too.” He was escorted out and told by Bill Graham never to come back. Which, I think, lasted for only a few years.

Jim’s behavior was often as outrageous as some of the music performers he photographed. He shot all the now dead “Big J’s” of rock and roll: Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, John Lennon and Jerry Garcia. In my opinion, one shared by many of the great photographers of the era, you could add Jim Marshall to that pantheon of “J” legends of the music world, who all died much too young.

Undisputed keeper of the flame is Amelia Davis, described on the website as “sole beneficiary of legendary photographer Jim Marshall’s estate.” She presents a softer side that’s just as searing.

Amelia Davis: I am a photographer myself and have a BA in Studio Art from UC Davis, where we studied fine art photographers like Henri Cartier Bresson, Helen Levitt, Man Ray and many others. I didn’t know who Jim Marshall was. When I graduated from college, I started showing my work in galleries, and it was during that time that my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. In going through the journey with her, I saw that there was a real need for a photographic book to show women what the disease looked like. This was back in 1994, and no one showed what breast cancer looked like unless you had a friend willing to show you. My mother’s only option was a modified radical mastectomy and she was devastated when the bandages came off. No woman should ever have to feel that way, so I took my camera and started to photograph women with breast cancer. It took me over six years, my own money, and though publishers agreed the book was needed, they thought they wouldn’t get their money back. After 56 rejection letters, the book was finally published by the University of Illinois Press in 2000, though not in time for my Mom, who passed away in 1998.

Bill Graham in his office, 1967 © Jim Marshall Photography LLC

Shortly after her death, I met Jim at a friend’s birthday party. This little man with a Leica around his neck saw me and made a beeline. He introduced himself as Jim Marshall, which was completely wasted on me. I didn’t know who he was! He asked what I did and I told him about working on the publication of a book on breast cancer. He thought what I was doing was amazing and told me about the many women he knew who had breast cancer—and that he thought Thanksgiving turkeys looked better when their breasts are removed. He offered to help and asked where I lived, which turned out to be a block away from him. We met for coffee the next day and hit it off. Jim needed an assistant and asked if I’d like to work for him, and I said yes. When I went to his apartment and saw all of his iconic photographs on the walls, I was really embarrassed not to have known him by name. But I sure knew his images!

I worked for Jim for the next 13 years. We became very close, like family, part of each other’s everyday lives. Jim always supported what I did with photography and admired what he thought were courageous photographic choices. I was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis and ended up publishing a photo book on people living with MS. Jim would always introduce me as his assistant, “The Disease Photographer!” Jim had no children; his photographs were his children. He told me that I was the only person he trusted to take care of his children. When he died in 2010, I became the sole owner of his estate. Jim’s archive is too important not to share with the rest of the world. He photographed pieces of history that won’t repeat, so I’m going through his massive archive and cataloguing it—over a million images in black-and-white 35mm alone!

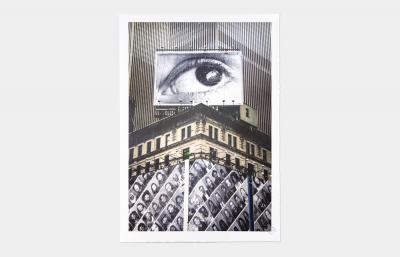

I found a notebook of his from around 1978. It was titled The Haight, and he had cut out photographs and pasted them on pages. About ten years after the heyday, I think it was too close to the time period to interest publishers who had not yet realized the impact of the era. I approached Insight Editions, and we looked through 5000 proof sheets from 1965 through 1968, finally winnowing down to 350 photographs. How lucky that they felt honored to publish this book, which chronicles a brief period that was so very significant in music, literature, fashion and counterculture. Jim photographed not only the musicians, but everything going on around them. He felt he was a historian with a camera. His curious eye was always looking for more things to photograph, no matter how seemingly insignificant, capturing emotions and moments in time through photography. The viewer becomes the participant. This was Jim’s genius, and every subject knew that Jim was the best in his field and wanted to brag about being photographed by him. The musicians’ trust in Jim is why he had all access.

JIMI-FIRE, Monterey Pop, 1967 © Jim Marshall Photography LLC

With 2017 being the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love, San Francisco is celebrating all over the city. When Meg got in touch with me about participating in a show, I told her that once she saw the book, The Haight, she’d realize no other photographers were needed because Jim had photographed it all! In curating the show, Meg came up with idea of calling it Jim Marshall’s 1967. She wanted to convey how much one photographer did in just one year, in Jim’s case, 24/7. We decided to illustrate that month by month. What an amazing story to tell, and, as Jim said, “Let the photograph be one you remember—not for its technique, but for its soul. Let it become part of your life—a part of your past to shape your future.”

Baron Wolman, Rolling Stone’s first chief photographer (In coversation with Eric Christensen)

My wife and I were living in what, at the time, was an edgy Haight-Ashbury. I was away on assignment when some neighborhood thugs broke into the house, tied up my wife and stole a bunch of stuff. She quickly got untied and called Jim who immediately came over armed and ready to defend her. For two nights, he slept on the couch with his gun, explaining that the police had given him permission to shoot the perps if they returned. I know he hoped they would... what a friend!

Henry Ditz, Photographer of The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, James Taylor and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young (In coversation with Eric Christensen)

I met Jim way back in the early ’60s, the folk scene in Greenwich Village, but we always saw each other and were both onstage shooting at Monterey Pop and Woodstock. I hadn’t heard from him in years, and the phone rings. “Henry, it’s Jim.” Well, I know a lot of Jims, so I said, “Which one?” He replied, “It’s your fucking guru.” And that he was.

Michael Zagaris, Rock and Sports Photographer (In coversation with Eric Christensen)

It was May of 1968 and I was working for the Bobby Kennedy campaign, but took the day off to go to the Santa Clara Folk Rock Festival, headlined by The Doors. I took a camera and two rolls of film, one roll to shoot a frame of the other bands and one roll for The Doors. I managed to get into the pit in front of the stage, and halfway through the show, I see a guy in a corduroy coat with a number of cameras around his neck. He got into a beef with a frat guy in the pit and pulled a knife on the guy, who immediately disappeared. I tapped him on the shoulder and asked who he was. “I’m Jim Marshall, who the fuck are you? I told him and asked, “Who brings a knife to a concert?” And he said, “That’s not all,” and showed me his gun. We became friends for life.

----

Originally published in the March 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.