“that my feet kept time with the sun’s imaginary

changing position, hoping it would rise

suddenly from scattered parts of my body

into the upturned apses of my eyes.”

—Alice Oswald, Woods etc.

Landscape I

The hill seems to get steeper as I climb it until it is nearly vertical and I am on all fours, grabbing clods of grass in my fists for purchase. The land here is concertinaed into improbable valleys. The top of each hill visible beyond the last like layers of torn away paper.

The house where I am staying, at the bottom of the hill, only twenty metres away as the crow flies, if it weren’t for the great rise of the land, is on a floodplain. The river bubbles up through the garden, mercurial. Herons step between the tussocks of sedge, the long grass, the sudden marsh. Frogs crawl out of the lawn. I share their instinct to clamber towards higher land. This morning I looked up at the hill with hunger, the crest of it licked with sun, and above it only the sky with its thin skim of clouds.

From this high vantage point, looking down at the scuffed trail of my ascent and then squinting into the sun as it continues to rise from behind the distant hills, I finally place myself. White ruminants in the field over there, chewing cud. The child’s drawing of a house, of a green hill, of a church with a steeple like pointed fingers. There the snake of the river carves a path through the valleys to that furthest haze of sea. A swell of small birds in my peripheral vision. That same twitchy feeling in my eyelid as I get with an aura before a migraine. The murmuration tightens, dilates.

I lift my hands up in front of myself instead. Make a viewfinder with the two Ls of my thumbs. I move the frame closer to my face, further away, pan right to left. The landscape within the square becomes estranged from the land on either side of it instantly. Though only my body, the cold-stung, reddening flesh of my fingers, bisects And even then, only for my eyes which look through the frame. The landscape is continuous. My fingers making contact with nothing but myself. The horizon is always out of reach.

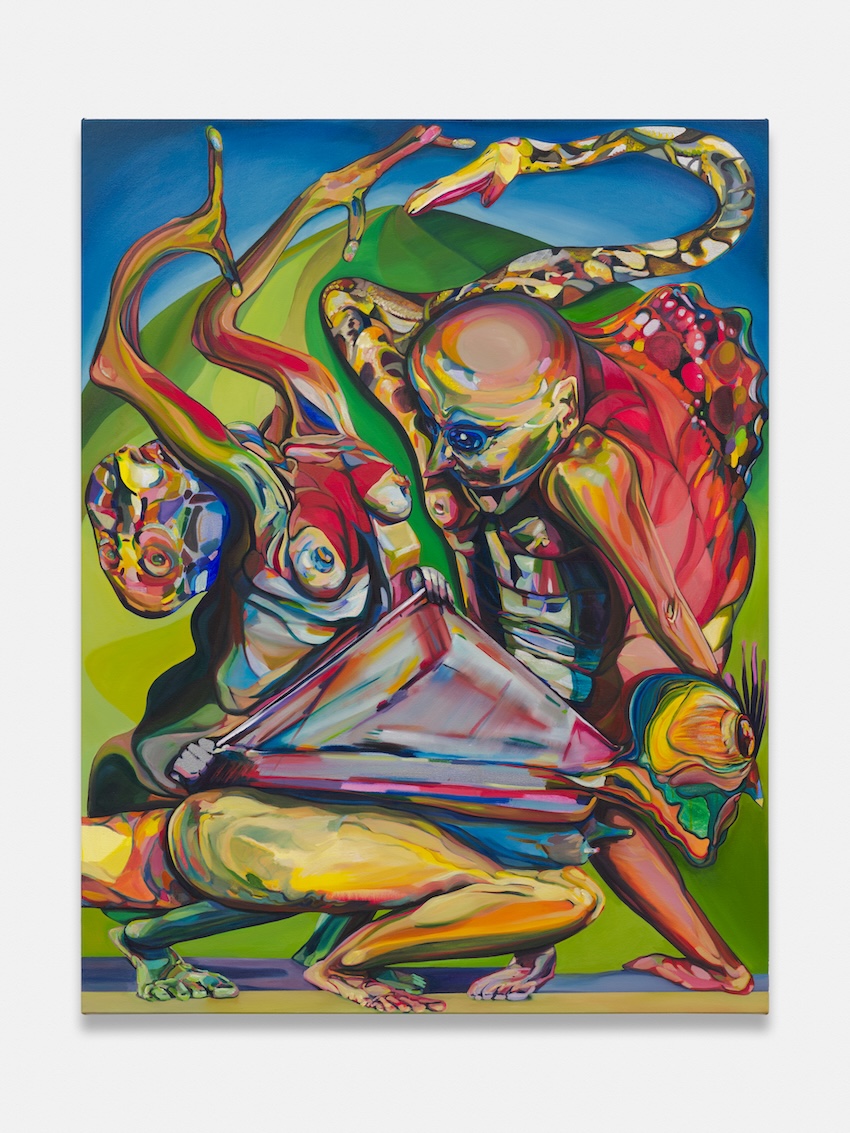

My first encounter with Emma Cousin’s ‘Landmark’ series takes place in her studio. Canvasses hang on each of the walls. I have the vertiginous sense that the paintings are what the walls look like underneath, like the white paint has been peeled away to show the hidden musculature of the world. Windows filter natural light in, offering a scaffolded view of the wavering London skyline. The draught lifts the corners of pieces of tracing paper that are tacked up by each canvas.

On each of these pieces of tracing paper, the private geometry of the painting has been drawn out. The arrangement of limbs carefully planned and scaled. In this way, Cousin reminds me of an architect, or a cartographer. There are still impulsive decisions, a responsiveness to the paint and the texture of the canvas itself, which are evident where the paintings deviate from the blueprint beside them.

These paintings began as landscape studies, largely made in Lyme Regis. And with this series, Emma Cousin asks how we begin to understand a landscape? Do we seek to understand it with data and calculation? With history and art history? Or do we call instead on our somatic body knowledge? How can we balance these methods of knowledge making?

When I think of landscape painting, I think of panoramic mountains of untouched snow and rolling green hills, endless sand dunes or silver tundra. Often I imagine these scenes empty, bereft of bodies and of the marks of bodies. Their track and tread, the trails of slime and grease. But every landscape contains bodies. Every landscape is teeming with bodies, both human and more than human, and it is only when we are pursuing the perfect beauty of the vista, the unblemished view, that these bodies are seen as trespassers. In ‘Landmark’ the transgression of these bodies is welcomed, encouraged even, until it becomes difficult to distinguish the body from its environment.

Landscape II

The black water is disappearing from view rapidly. Looking across the cavernous valley, the clouds sweep in beneath us. The air is sodden, charged. We are within the cloud, rather than below it. We watch lightning bounce from peak to peak, in sequence. It flashes most spectacularly, purple like a vein, on a stony outcrop, within which three villages are nestled, so that from here, at night, the lights of them make a face. Two clusters for eyes and a longer, thinner trail of civilisation makes a disappointed mouth. In Norse Mythology, the Earth was made from the rent body parts of a giant called Ymir. His blood formed the oceans, his bones became mountains, trees from his hair and the canopy of heaven from his vaulted skull. That would make us his neurons I think, our fingers starred and stretching towards each other.

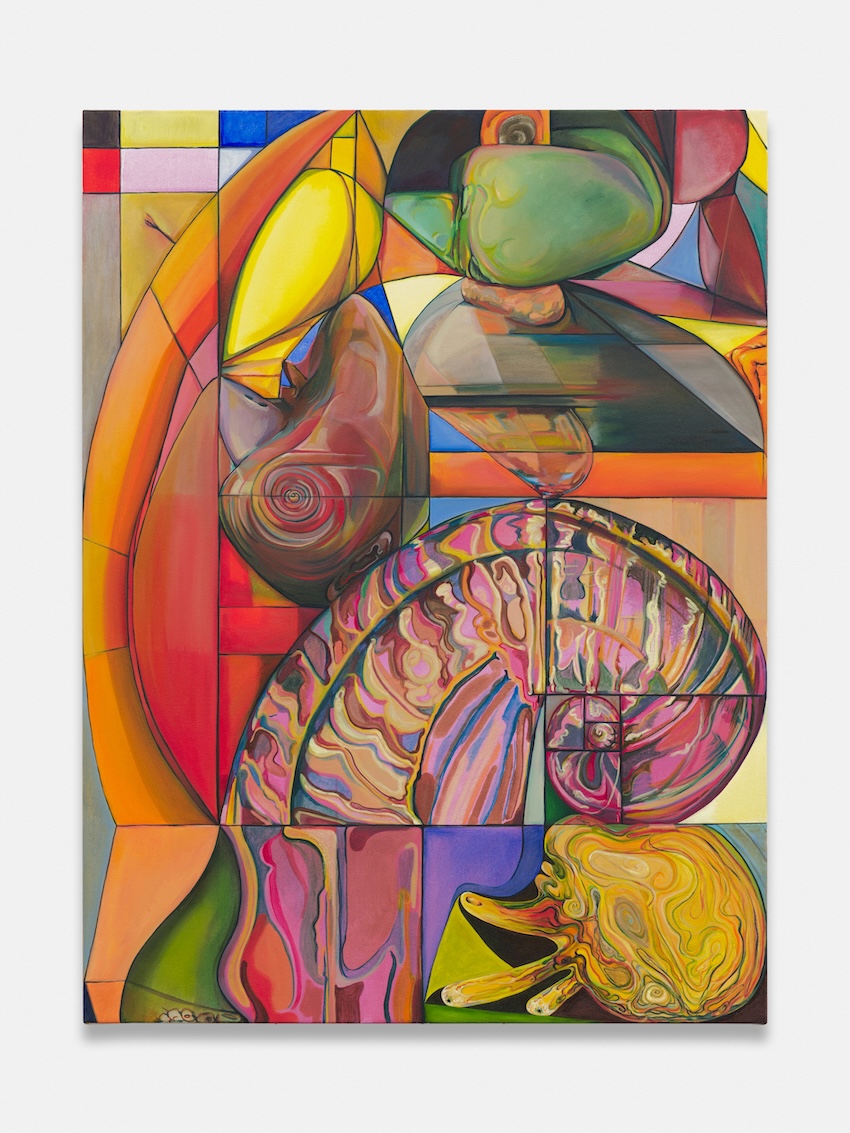

In Fossa, the snail painting with the fewest discernible human figures in it, the mathematics is most noticeable. The scaffolding grid remains, dividing the painting into regions, like the sky through the windowpane.

The main form in Fossa is the Fibonacci swirl of the snail. Though they are named after a 13th Century Italian mathematician, the Fibonacci sequence was first described in around 200 BC by Indian Mathematicians, including Pingala and Bharata Muni, creating formulae for metre in Sanskrit poetry. We find the endlessly spiralling, fractal forms produced by the sequence hypnotic and meditative, whether we encounter them in poetry, musical harmony, or in nature, in tree branching, in the complex spiral of seeds in a sunflower head, in pine cones and artichokes and roses and snail shells.

Cousin’s son is going through a snail phase, she tells me. Fossa means to dig. His fingers in the mud, the mulch, under the lips of plant pots. The root of fossil. The snail like an ammonite. The magnetic tug of her son’s curiosity drawing her back through the spiral of years, the unwinding of time to that same child state of play. The soft foot and glittering body of the snail emerging from the shell, tentacles first, waving in the air. Snails possess limited, fuzzy eyesight but the long tentacles on which their eyes sit also contain well developed scent sensors. The rest of the snail’s outer skin contains cells to detect smell, taste, touch, humidity and temperature. They cannot hear, but they can probably feel vibrations through this skin. The snail and the toddler both put leaves and mud and other snails in their mouths.

Watching children play and explore is excellent evidence for the primacy of perception. While scientific and analytic faculties are still nascent, their knowledge comes from their body’s exposure and encounter with the world. This mode of being in the world, body first, is described in Talia Welsh’s “The Child as a Natural Phenomenologist”, a summary of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s writings and lectures on child psychology. “Merleau-Ponty describes initial human experiences as displaying a syncretic sociability where the infant does not distinguish between herself and others or between herself and the world,” like we begin our lives experiencing the world as a primordial soup, where we are porous, edgeless, mixed up with our mothers, the water we are bathed in, the snail. Philippe Rochat disputes this total melding in his “Five Stages of Self-Awareness”, arguing that infants can at least differentiate between self and non-self touch from birth. There is a sense of my body, which is separate from other not my body entities. This knowledge is somatic, not intellectual. For the infant, those not my bodies only exist when they come edge to edge, skin to skin with my body, and likewise my body as a piece of knowledge emerges from the encounter with the other. This self-awareness amounts to a distinction between two types of sensation. And this is the base rock of our own mature self-knowledge; the feeling of grass underfoot, your mother’s smell on fabric, which does not smell like your own, the difference between the heat of your own hand in someone else’s.

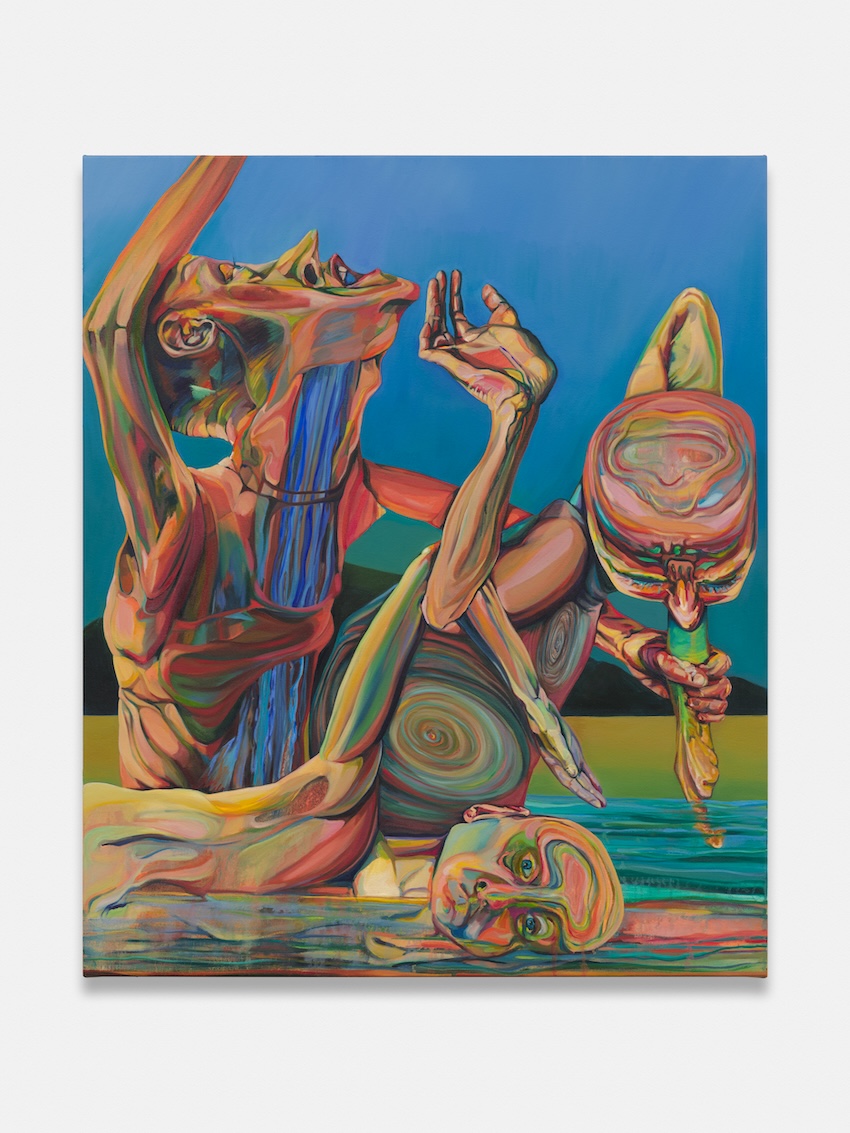

This somatic mapping of the world and the body is evident in ‘Landmark’ where Cousin paints body parts in proportion to their sensory significance. So the hands are large, as are the noses, the mouths, the eyes, while many other parts of the body may not appear at all. Further, it is the moments of contact between bodies that really stand out. In Headwater a nose pokes out from the hinge of a knee. Right at the bottom of the frame, in the silt of the painting, two sets of toes kiss. It is a touch so glancing that you might overlook it. Except it is precisely in moments of touch like this that the body finds its edge. In other paintings, the touch is more desperate, weight bearing. In Cover Point the sinews of the limbs pop and stretch, a thumb grips round the ankle of a foot with flexed toes.

Elsewhere in Cover Point one of the figures appears to be eating, perhaps kissing, a plain of green earth. Throughout history, soil eating, or geophagia, has been practised for medicinal purposes, mostly to ease stomach pain and menstrual cramps. But this figure also seems to be trying to imbibe the landscape in order to merge with it, to blur the boundary between the body and the land by swallowing it down.

In the first chapter of Samuel Beckett’s Molloy, Molloy visits the seaside and fills his pockets with sucking stones. Rotating the stones round his pockets, Molloy tries to perfect a system for sucking each of them in turn. The passage becomes an intricate description of the calculations of this puzzle, this game, in which the solution in the end is to discard all the stones but one. What makes this passage most game-like perhaps is that there are rules, ‘principles’. One of these is that the stones must be equally shared between his pockets at all times. When he trials a solution without equal distribution, he experiences a feeling of yearning, a bone marrow feeling of wrongness. “There was something more than a principle I abandoned, when I abandoned equal distribution, it was a bodily need.” All children can recognise this feeling. When the rules of the game are broken, or undermined, by themselves or another player, children have a strong sense that it feels wrong. All children also know the drive, the conflicting bodily need, to test the constraints of the game and propose new rules, complicated exceptions, mitigating circumstances, to find loopholes, cheat, call time out just as they are about to be it. The game collapses. There is a stage of childhood development when more time is spent determining the rules of the game, world building, than playing.

In the spirit of play, we might also see the figures in Cousin’s paintings as trying on the landscape, by trying to fit their bodies into the landforms. This might sound strange, but we have all done it, and we know the euphoria it unleashes. Think of snow angels. Arms window wiping in the cold. Standing up, looking proudly at the mark your body has made. Imagine lying on the grass and recall the impressions it leaves on your skin. My mother tells this story, one of her earliest memories, when she had fallen into a stream and instead of standing up to protest she just lay there in the water, looking up into the sky. The water wasn’t deep enough to overwhelm her, only to clothe her for a moment. I think of this moment each time I look at Oolith. The figure lying in the water, staring out, and above the great planes of perfect blue.

Landscape III

My gums had bled for several days, so that the only thing I could taste was tin, and the bitter throat drip of dissolving painkillers. From the window of our room, I can see Cave Hill. This is the city with a mountain at the end of every street. No matter where you stand in this place, if you raise your eye line just a little you will see a smudge of green warbling the horizon. Cave Hill is named for the giant cave that opens on the side of it, like a worm eaten apple. It has another distinguishing feature, however. The topmost ridge falls away suddenly in a vertical cliff, known as Napoleon’s Nose. Both of us have lost our sense of smell. It is a sweet irony to hike this huge aquiline formation. I climb unsteadily, needing to pause frequently to lay my hand on a mossy rock and rest. I stumble over every rabbit hole, punched into the land like wide pores, I trip on every mole-like tussock. We could turn back. We don’t. I want to be out, I want to be up, I want to be standing on that cliff edge that I have been looking at hungrily for days, which has come to be for me the absolute quintessence of outdoors.

At the tip of the nose, we pause and look out over the sprawl of Belfast. I stretch my wingspan to feel the wind buffet and buoy me. I am this big, this big in this huge world, in which I am not even a speck to someone standing on the road down there, or looking out of that distant bedroom window, and yet from up here, I can see out and over. I can take them, and everything, in. My nostrils flare and contract as I inhale.

In ‘Landmark’, as in many of Cousin’s other work, the bodies are impossible. Body parts and faces twist and contort, limbs bending backwards, necks craned, arms pretzeled. These bodies are riddled with tumours and gouty swellings that mushroom from knees and ankles.

My body is an impossible body. A surreal body. I can step through the circle of my own arms, wiggle them up my back, then fold my head through without unlinking my fingers. Sometimes when I put my hands on my lips it looks like my arms are on backwards. The Beighton Score is a series of five movements (with movements 1- 4 being performed on both the left and right sides of the body, to give a total possible score out of nine) used by medical practitioners to assess hypermobility. My body had a perfect score.

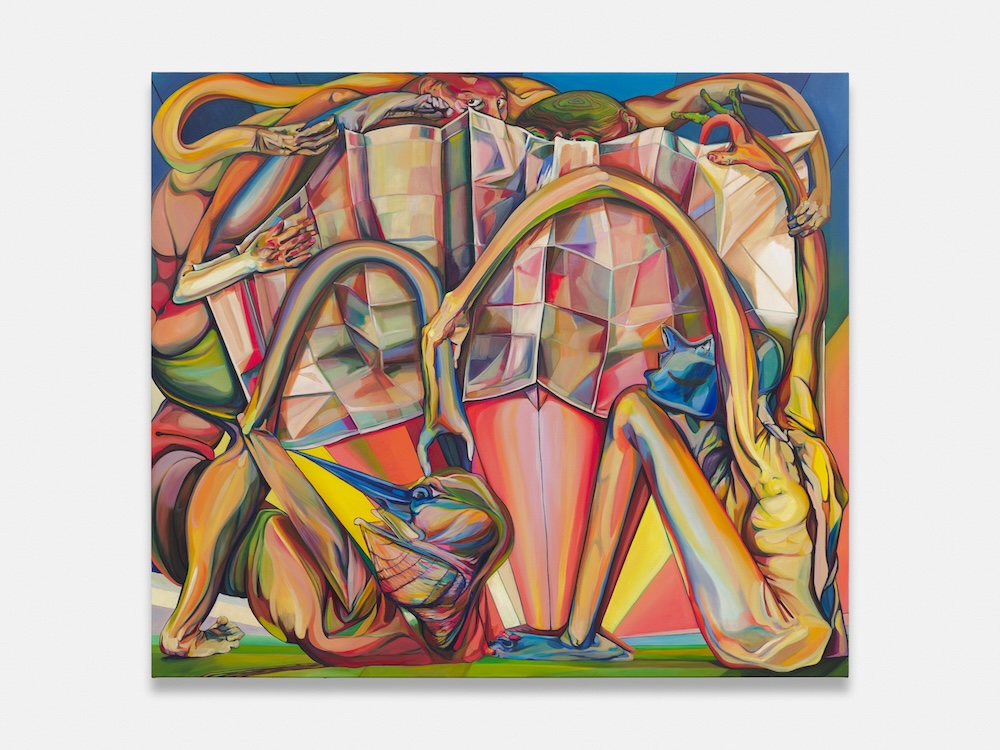

One summer when I was thirteen, before I knew I was hypermobile, I went on a summer camp in rural Wales which involved a long four day hike. Coming down the shale path from Snowdon, both my ankles rolled and I plummeted, my heavy backpack dragging me down the side of the mountain like a millstone. I spent much of the next week being carted around in a wheelbarrow, my knees, ankles and hips never quite regaining their stability. I am brought right back to that hike when I look at Pelican Vale. The spaghetti armed figures straining to encircle a huge map.

The map is the world unfolded, the landscape flattened and gridded. Each creased square is like a field seen from above. Instead the human bodies around it bend to make the curvatures of hills. All the paintings in ‘Landmark’ have a cartographic quality, of which Pelican Vale is the most didactic. In all of the works you will find circular lines arranged concentrically, like land contours. The planes of colour, bisected as they are with outlines, remind me of the British Geological Survey maps, in which each colour denotes a particular kind of rock.

These rocks describe the history of the earth from the creative violence of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes, to the slow shifting of the coast by the licking sea. A core taken from the land will be striped with layers, soil horizons. These soil horizons are a key motif in Tartar, titled after the sediment that builds up on our teeth. ‘Landmark’ began its life in Lyme Regis, where Emma Cousin was undertaking a residency. There, alongside the clay cliffs that provide such excellent fossils, you can also find ‘Granny’s Teeth’, a set of steps leading from the lower wall to the upper wall of the Cobb. Though man made, these steps are so exposed to the sea fret and the countless hands and feet that touch them everyday, that they are changing shape, taking on the burnished form of sea smoothed pebbles, of sucking stones. As Granny’s Teeth have been altered by the many people who have scrambled up and down them in pursuit of fossils or a sea dip or ice cream, so are all our teeth shaped and stained with the history of our appetite and desires.

Perhaps Cousin is telling us that history is not an arrow driving forward, but the slow accumulation of layers. Of plaque on white teeth; of fresh new growth gradually sloughing off old skin; of last year’s soil being weighed down by new rot; the snail’s shell, which begins as a mucus-like secretion from the shell gland, then swirling onwards continuously with each ring that is added; like the rings in trees counting the years; like painting, and thinking, which both begin as an amorphous, wet and muddy slurry, until they crystallise, harden, and take shape. As in Delta the stalagmite grows within a bulbous shape like an egg timer. It is formed from the regurgitate of the face above. Time does not pass but is amassed.

Landscape IV

High summer. Lying on my belly on the lawn of my granny’s garden. The damp from the earth is seeping into my clothes, cooling me pleasantly. I am incredibly still as I can be when I am watching. With my eyes so close to the grass, my retinas are flooded with unending green. Until a cabbage white flits past. I lift my chin to follow it. It dances lazily past my eyes again and settles nearby on a blade of grass. I study the black eyes on its wings. This one has two conjoined spots on each wing, like ampersands. I think about stretching my fingers out to touch it, but I am distracted by a ladybird that is stumbling over the immensity of my small hands. It teeters on the apex of my knuckle, and falls into flight. When my eyes track back to the butterfly, it is also gone.

Cousin describes drawing as a way of “reconnecting [her] and [her] hand.” When I look at the paintings in ‘Landmark’, I am reminded of life drawing classes. Flexing my thumb against a pencil, holding my arm out straight. Our bodies are our first measuring tools. We count horse heights in hands, our own in feet. A fathom was originally the span of one’s outstretched arms, but is now standardised to 1.8 metres. I remember at primary school being told a metre was about the same as my arm span, middle finger tip to middle finger tip, and crucifying myself on tabletops and against cupboards to see if this was true. There are also the self-referential rules of body proportion. We say our two fists together are the same size as our brain, that a single fist is our heart, that arm span is your height (somewhat longer than a metre now, but not quite a fathom). In all of the paintings in ‘Landmark’, the bodies could be used as indicators of scale.

But from what vantage? From the view of the child lying in the grass, or the adult looking out across Belfast? The data we get from the body is always relational.

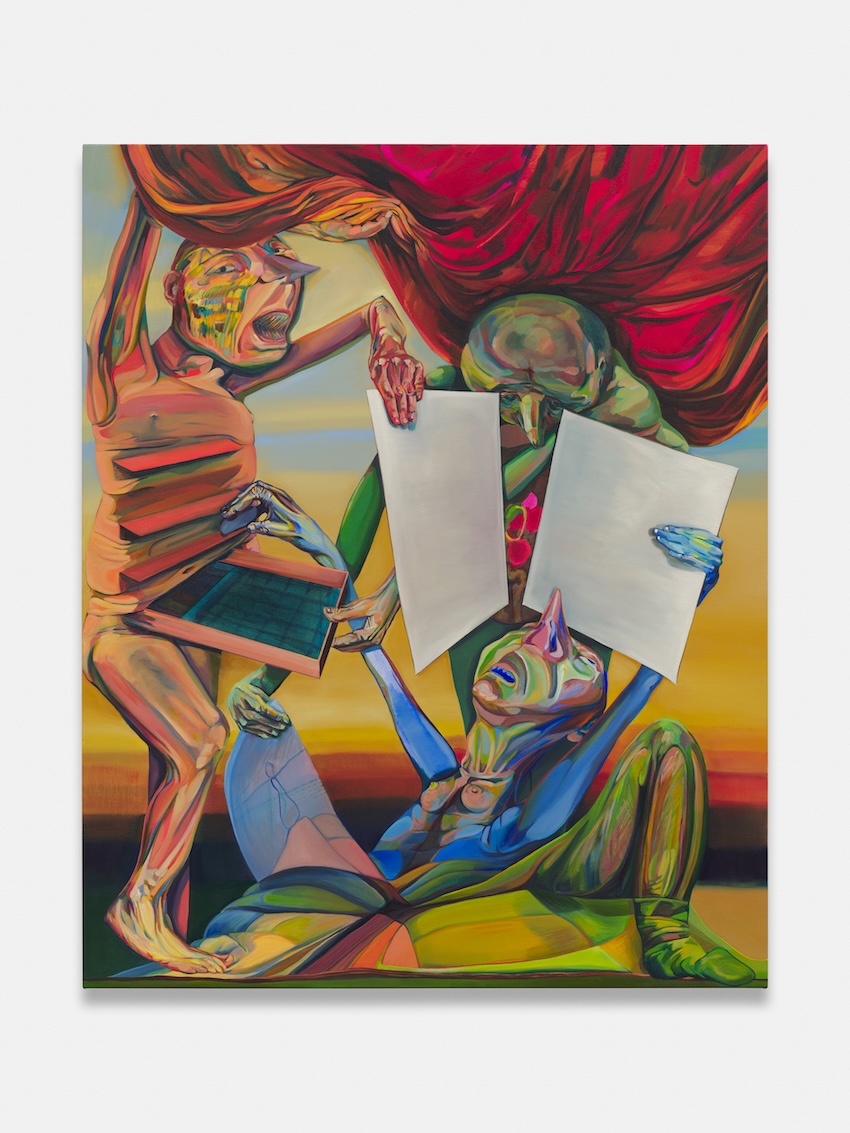

Milkweed is inspired by lepidoptery, butterfly collecting, but it also seems to be an invocation of the idiom “I have butterflies in my stomach.” I have always loved that phrase. The figure on the right of the painting, partially obscured, might be our shy collector. This collector figure pulls at the skin of the figure below him, the skin on the thighs that peels into butterfly wings. The collector figure’s other hand pulls open one of the drawers from the left hand side figure’s torso. This left hand side figure appears to have trays and trays of stilled butterflies in his stomach. Maybe the butterflies have been brought to heel, but the mouth which opens like a basking shark suggests not.

I do not understand butterfly collecting. I once found the perfect still form of a dragonfly on a picnic bench outside my office. I lifted it gingerly and was surprised by its lightness. I put it into a slightly soiled sandwich box and carried it home. I must have looked at it once or twice, but in truth it made me sad. Even its body which retained its astounding, iridescent turquoise colour seemed dull. It was a body made for movement, perfectly designed for it, and ill equipped and poorly proportioned for stillness with its tiny thread-like legs and copious wings. I cannot think for the life of me where it is now.

When I think of inserting a pin into a butterfly, I am brought back to the futility of life drawing. There is always a certain amount of failure in trying to capture something. The harder you look, the less a subject behaves like itself. To study a butterfly it needs to be still, but once it is still, it has lost a significant part of what makes it a butterfly. Attention becomes abstracting.

I have spent too long looking at these paintings. Like after staring at the sun, the echoes of them linger even when I close my eyes. The figures are transmuting. In Pike see how that arm might be a snake. That body might be cocooned and souping into a butterfly. The landscape and every body in it eats itself before it is resurrected. Even now. You have watched me plot the vast and wild territory of my body through many landscapes. I have tried to find my landmarks, to place myself, but I am less certain of my boundaries now, not more and yet I keep looking at.

Landscape V

I bring myself to the coast, to the outline of the earth, where the horizon is widest, and the vanishing point bristling at the end of my pointed nose. I am at Lizard Point, the craggy tail of this landmass. This is the edge. I line my toes up with the rock. As close as I can get to it. Closer if I balance on the balls of my feet, so I can peer right over the promontory of myself and see that there are stones under the water as glossy and slick as the jellied inside of my torso. My skin is pinking. I am here at the edge of my body, my skin as thin, as porous, as liminal as the meniscus of mist that splits the ocean from the sky. Constantly water moves across this membrane. I put my hand out and I swear I can feel the still wet paint on my fingers but it is just the rain.

---

Text by Vida Adamczewski

This essay was written on the occasion of Emma Cousin's solo exhibition, Landmark, which was on view at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco in late 2024.