When we think about utopia, we might think about the end of hierarchical society or a world of abundance that nourishes everyone—all that to say, a woman’s freedom to enjoy sex and feel no shame for it isn’t typically thought of first and foremost. But why not? As it stands, our current world is not one where sex and pleasure are synonymous for many people. In a society that is perfect for all its members, wouldn’t these two things be inextricable for everyone?

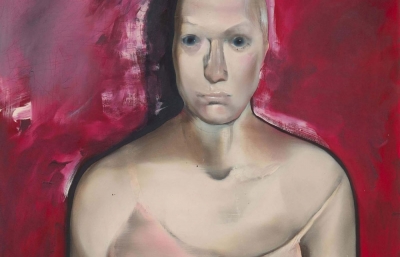

Dutch-painter Martine Johanna wonders this in her solo exhibition A Particular Ghost at Hashimoto Contemporary Los Angeles. While the scenes of women in ecstasy and grief are not depictions of this “utopic” reality free from oppression and inequality, the paintings do prompt us to wonder why something seemingly so simple has not been made real. Pulling from her own experiences as a woman and the moments that continue to haunt her, Johanna locates a piece of herself in all other women, hoping they might attempt to rid themselves of the shame society has placed on parts of their bodies.

Before the opening of her solo exhibition, Johanna spoke with Hashimoto Contemporary’s Katherine Hamilton about the dichotomy of public and private self-image making for women, why it’s both liberating and challenging to depict these intimate or vulnerable moments, and the history of male power in art history that frames women’s bodies as harmful.

Katherine Hamilton: Much of this work is about your own perspective as a woman. While you deal with broader themes on the perception of women in a patriarchal society, you draw from your own experiences and memories rooted in womanhood. Firstly, how do you relate to the female figures in your paintings? Are they versions of you, women from your imagination, iterations of women you know

Martine Johanna: My work is autobiographical in nature, so it’s about my own experiences that created my view on how I see myself within society. The outcome is something just far enough from the literal to become more abstract and relatable to others. I see it more as an emotional spectrum, not a physical manifestation like a photograph. It’s a translation of anger, strength, vulnerability, escapism, and oppositional feelings. The escapist part is very much present in this series of works, almost to balance out the confrontational works.

Would you consider this a particularly vulnerable exhibition for yourself?

These past couple of months I have been in conflict with myself over the exposed pieces. Every time I walked into the studio I felt a whole spectrum of emotions, including fear, shame, feeling exposed... In fact, sometimes I hated those paintings. I would feel uncomfortable within myself for painting them, and then uncomfortable for feeling shame.

You hardly see aroused female genitalia in painting—it’s not a normal thing to portray women in lust in the same way we often see men in lust. I absolutely hated my works but loved them at the same time, even in their almost kitsch stylized depiction and vulgarity. But all those negative emotions towards something completely natural and part of me (and others) confirmed to me that I had to finish and show these works. I asked myself, and wanted others to ask, why would it be literally harmful to anyone?

Right, a couple of the works in the exhibition show more explicit parts of women that society has deemed too “harmful” for widespread viewing consumption. Can you speak more to the idea of “harm”?

If you really look, the harm is not in the pleasure, the harm is in the judgment a woman faces around the idea that she derives pleasure from sex. The harm is the censorship of real abuse; the true harm is in judgment, in labeling a female worthless when she has desires, her nudity is feared, her body is policed. However the female body is not a danger, our bodies are not harmful but round, warm with no sharp edge. We are as close to nature as our male peers and should be able to have the same safe freedom and respect.

Titles of works like A Round Object Has No Sharp Edge point to the fact that the female form is perceived as both harmless (soft, helpless, in danger) and harmful (widespread censoring of women’s bodies and depravity associated with “impurity). How do you as a woman live through these double binds?

We as women generally have the same desires as men, maybe even more deeply and passionately because we often connect more on a complex emotional spectrum. Desire is also more exciting when it is something “forbidden,” being devoured (by someone you trust), feeling an immense freedom of expression when you are able to be submissive or in charge, it is always the contrasts that make things so exciting and liberating. However, it only works if both parties choose it.

I also want to talk about the different mediums you use to expand your practice, like writing. Are there any ideas you’ve been able to explore through your writing practice that may have been more challenging to execute in painting or other forms of visual expression? Where do you see the two mediums converging?

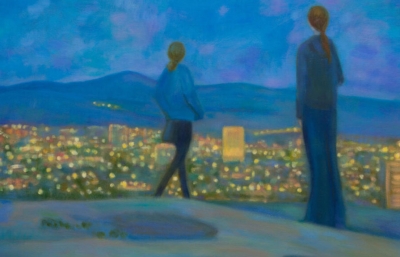

In my writing I am perhaps more capable of creating whole narratives than in my painting. This time I explored more how to depict the worlds in my mind in the way that I write them. In that way my writing has influenced certain choices, such as the landscapes and interiors. I feel very excited about those works because they offer a whole scala of narratives, like stills from a film.

I’ve had extensive therapy treatments for complex PTSS these last years. My mind is still easily overwhelmed. I always have layers of thoughts, and when I’m under pressure these layers begin to intertwine and I get a lot of noise in my head, like switching radio stations with static, music repeating and faint conversations. It’s also partly visual with images and when I manage to sleep without medication, I dream very chaotically with repeating dreams where I’m always in houses and traveling in dysphoria. Whenever I wake up, though, I make notes on what I saw and how it felt. So, in conclusion, I am the haunted one, and the images I chose to make for this show are both independent on their own and also flashes from one connected narrative.

I wanted to touch on your conception of landscapes within these works and the religious idea that women are closer to nature. Some works appear figureless, showing dream-like renderings of different environments: a boardroom table inside the Northern lights, an X-ray vision of a sunset through a forest, windows and portals that seep fog from another world. I know you mentioned that women’s bodies are a part of the natural world in this body of work, but these sporadic landscapes also seem to allude to “a safe adventure” that ties the works together.

The common denominator is that all these works are somehow landscapes, scenes and momentums that come from my imagined world, they are non existing but very real to me and full of possible adventure, within the safety of my mind. The idea of women being closer to nature is so commonly embraced because we can carry a child, which apparently means we would somehow have a more intuitive nature. However, empirically, we are as close to nature as men, and yet this association of women with nature also suggests that men are closer to God, making them slightly closer to power. Nature from the middle ages is unified with the earthly idea of the devil or evil, a woman (Eve) is of a lesser value and inherently more evil than men, it’s a subtle religion originated idea interwoven with society's view on the value and distrust of women.

Something about the works with nude figures reminded me of historical paintings of the goddess Venus, particularly Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus,” and her emersion from the land (a shell), the way she covers her pudendum with her hair, signifying demurity. To me, these women seemed to be responses to the long history of men painting allegories for idyllic beauty. Though “escapist,” there’s still something raw and honest about your figures. When making the works in A Particular Ghost, were there any artworks you were looking at, whether through a lens of critique or inspiration?

I think just intuitively these associated shapes and symbols come to exist in these works. Somehow I have really avoided modesty because that to me derives purely from religious and patriarchal perception. Do we measure men’s behavior by the same standard? The old masters depicted rape, judgement and modesty as a way to educate women. Look, here is what happens when you behave a certain way. Whilst what I show is the purest form of intimacy you’d want with a safe and free person, without that judgment. The hands in the explicit works are of an unknown person because I wanted to focus purely on the female presence. So even if her partner is anonymous, or a fantasy, it should not matter.

There’s a sense of pleasure permeating through the artworks. Can you describe your desire to depict these women in such intimate situations? Do you see it as a form of liberation or more like a view into private thoughts or fantasies?

Liberation, absolutely, because I still deal with the emotions that I have to face when showing these works. These private thoughts or fantasies are generally not an acceptable expression coming from women. Whilst men generally would have the freedom to take pride in their lustful fantasies or adventures.

Much of your work has explored the dichotomy of public perception and private self-image for women—as though we have two (or more) selves that navigate the world depending on who the “viewer” is. You’ve mentioned that you, the painter, embody the eyes of the women in the scenes, reporting private, interior moments the public would not usually witness. Is there an exhibitionist element to revealing these “private” moments?

I don’t think so, for me the abstraction of my style has the inherent effect of a translation that feels distant enough to be able to feel safe. Also the narrative is so relatable that many people can connect somehow. They also inhabit themes of fleeting time, of desire, of whirlwind feelings, all these things are relatable to any sexes.

Your previous works showed a world where women seemed to be escaping or fleeing somewhere. How would you say the works in A Particular Ghost works relate to “escapism”? In part, it seems they depict a world where giving into lust is not only tolerated but perhaps encouraged rather than a world that runs from sexuality.

These works are about accepting and embracing that everyone is equal in worth, and I'm not even addressing, “should be,” but IS. Sexuality is a big part of that, but freedom of expression, adventure and development as well. Because for those that are seen as weaker, the fear of not having safety, respect, equality and freedom is always something holding you back. Those who are perceived as strong in society have a natural autonomy, because they don't have to consider those things.

I also want to touch on the more solemn aspects of this group of works. Works like Ritual For a Small Death or Silent show young women gathered, some bowing their heads, perhaps in grief. You wrote that, through this show, you hoped to “unravel a poetic type of loneliness within the social construct that has both harmed and celebrated [the artist].” How did you approach loneliness throughout this exhibition? You seem to weave it in and out of each work.

I think loneliness is a part of any trauma that is not visible from the outside. Especially when shame is involved it becomes extremely lonely, because somehow you feel responsible for bad things that happened to you. That's what I was taught and what is taught to all who are seen as weak. Ritual For a Small Death for instance refers to both a female orgasm, the shame, but also a loss of virtue, or literal losses we women face and are often not addressed because you need to move on or you should be ashamed of your contribution to bad situations.

Finally, you’ve depicted many, many women throughout your life as an artist! In an ideal world, what are they doing right now? What might they be doing tomorrow?

These women are just the ghosts or fragments of myself and other women or even other persons that suffer similar issues, visualized as a dialogue. In an utopian situation they would cease to exist, because all their turmoil is what created them in the first place. Utopia as an unattainable desire, to me, is just a similar world, where every person can be free of oppression, and there are no people that are seen as possession or as weak. What that would probably mean is no religion that oppresses, a healthy environment and no more poverty within healthy competitive economic systems that are not exploitative.

A Particular Ghost in on view at Hashimoto Contemporary Los Angeles through February 03, 2024