Prudence Flint

Portrait of the Unnamed

Interview by Charlotte Pyatt and portrait by Anna White

Whether filtered by an Instagram hue or loaded with pointed symbols, a portrait offers more than a likeness. Beyond appearances, these ghosts can recall transience and texture, as well as a point in time. 2019 offered a beautiful tragedy of subject matter, a litany of broken theories and prejudices about our world and each other, that we are trying to push into a healthier direction. Exploring this process of reversal is Australian artist Prudence Flint, who reflects on a history of misrepresentation as she creates space for new empowered realities.

Presenting thoughtful women in moments of quiet contemplation, Prudence hosts simple rooms free from the distractedness we battle daily. In these intimate spaces, we join her characters in the rhythm of everyday life. Their ordinary beauty is an expression of the unnamed, a journey of discovery for the true identity of womanhood, buried in history. Filled with social and cultural commentaries, Prudence unpacks ageism, violence of language, and the anxiety of men to reflect sincerely on her own experience as an artist and a woman in the present moment.

Blue Cotton Dress, Oil on linen, 43” x 56”, 2017

Charlotte Pyatt: Your style is typified by female characters inside of the home in moments of thought or everyday activity. Could you tell us a little more about your creative direction?

Prudence Flint: I am fascinated by how women have been represented historically in art and in the media. I think, all through time, women have been up against the limitations of their representation. They have been written out of history, their reality “unnamed” and denied meaning. We are so accustomed to this, and it is ingrained in our culture everywhere we look. It is as if women are unrecognizable if unrelated to male desire. Women are always in relation to lack, constantly up against unconscious bias. I wish for women to be at the center of things… to be all things, whole, boundless, perverse, and representative of humanity. I want to give voice to this experience of being alive, now, in this culture, as a woman.

This experience seems to focus on the mundane, almost ritualistic behavior; brushing your teeth, showering, getting ready. Can you talk more about this?

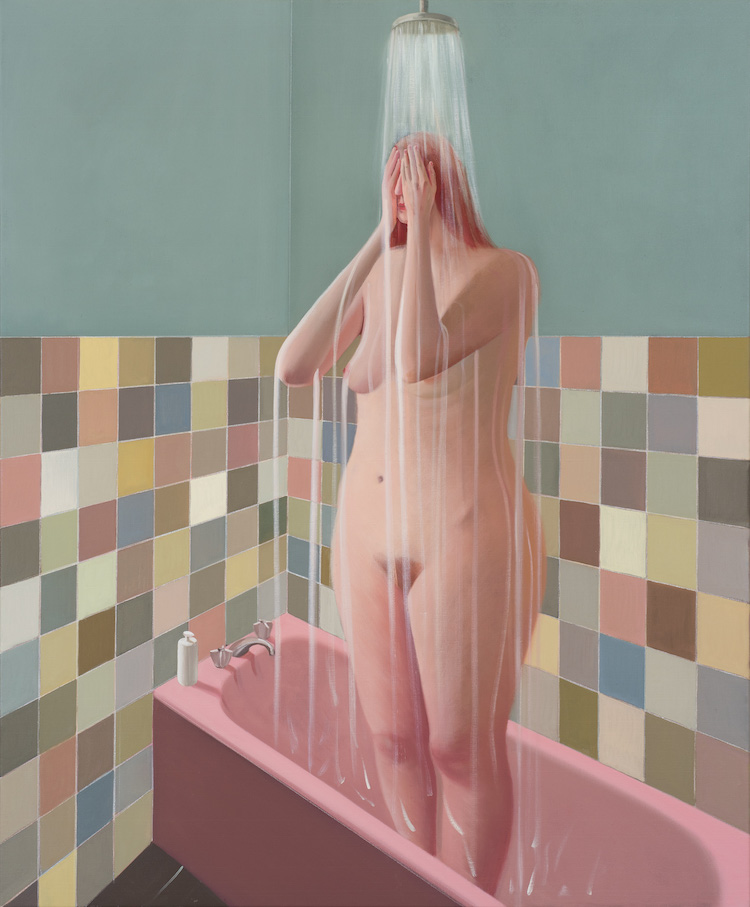

I’m interested in trying to capture existence. These simple tasks are universal, where bodies are in rooms interacting with water, machines, hard-shaped surfaces. Bodies have movements: brushing, washing, cleaning, spitting, eating, sewing, writing, and playing music. I think the bathroom, especially, is a primordial place when it comes to our psychology. As babies, our mothers bathed us, we were naked and in water. It is a private space where we are in our animal bodies. A woman sitting on the edge of the bath or standing inside it. I think about the vessel and the body of water as uterine, and the flowing movement; it feels female, vaginal, open.

The environments housing your characters have become increasingly isolated over the last decade, moving from social spaces and tasks, to sparse interiors and sitting alone. What motivated the change?

I think this was probably very reflective of the life I was leading at the time. In the older works, I was physically engaged. I had many responsibilities and I was driven and channeled my libido into tasks and activities, my energy sublimated. Now both my parents have passed away and I am experiencing a level of new freedom in my life that my mother and many of my friends have not, and now I find myself faced with the questions of existence. This idea is both terrifying and exciting. I am now more interested in addressing female sexuality more overtly. For older women, the representations are pretty bleak. Women need to be strategic and clever to find space and freedom in a patriarchal world. They have to embrace perversity to find any freedom and live an erotic life. They have to break the symbolic law and move outside acceptable parameters.

How does a woman find space? I have my studio, and it’s one part of the world where I am in control and I get to play out my perversity unabated. I have to give myself room to be larger than my life and think myself through a problem, and I am compelled to take risks; otherwise the work goes nowhere. I have to challenge myself. It needs to feel dangerous. I need to push up against myself and thrill myself.

As you get older, do you feel these limitations, and how do you think it affects the reception of the work when you offer these issues a platform?

Visually, older women carry a symbolic function. We are the horror movie of culture; we represent death and loss. It’s a powerful place. We used to be burnt at the stake. It carries weight. It is a blind place. I know this because I confront it when I try to open up to new images to paint and see how my images get read and responded to. I too am blind, but I want to see.

All my works are drawn from experiences in my life; how could it be otherwise? As a woman, I feel constantly up against the idea of what is meant to be happening to me versus what is actually happening to me. Where I have painted characters with grey hair, or hanging flesh in my work, the scenes just become so overpowering to the narrative that it becomes an abject distraction. I think I have found a solution by distorting the bodies, which becomes representative of what experience does to you. It marks you and creates emotional weight.

Is the absence of men in your work intentional? Is the male audience a consideration?

I’m not sure? I have found some men really enjoy my work, and sometimes, I’ve been told they run from the room. I’ve only recently been interested in painting men. There is one man shown and he is laying on a bed exposed. There is a lot of anxiety about the fact he is passive and resting. This amuses and fascinates me.

I feel like there is so much unconscious blindness when it comes to gender. I feel that change is happening, but slowly. Women are too thin, too fat, too young, too old; there is so much violence in the language used to control women’s bodies and it seems tangled with notions of power.

You have a passion for literature and film, and I wonder if this theatre impacts your creativity or process?

I read a lot of fiction: classics, crime, romance, contemporary, experimental, and watch a lot of movies. I love a female protagonist. Paintings are the ultimate intimacy and independent practice, distilling this process to create a single intense moment.

I will sit with the canvases for months at a time. They come together by surrendering to a process. I have to let myself sit and spend time and inhabit the painting and see where it takes me. I need to embody the figures and to let the tension and complexity reveal itself. I have to feel the discomfort of the work not being what I want for quite a large part of the painting process. What works in a small drawing doesn't necessarily work in a painting. A painting has to work on several levels. Paintings have surface and body. The narrative needs to hold ground with a painting tradition; it needs to talk to other paintings throughout history.

Color seems central to amplifying this intensity, so this must be a conscious choice?

Color is definitely the key to the creation of atmosphere. There has to be an unconscious harmony that holds the idea; allowing the soothing colors to sit along the more pared back colors. I'll push the colors back with their complementary to make the canvas sit as one, creating complex relationships. I know the color is working when I can stand before the canvas and it glows and holds together.

The reduction of space and play with perspective is about cultivating an environment that feels emotionally convincing. I am not interested in following photographic logic. I relate much more to this haptic logic.

I admire early Renaissance paintings. There is something heart wrenching about them, where there was a clear purpose and intention to their message. In a crucifixion, annunciation or a lamentation, the narrative had clear reason and emotional logic.

“When it comes to images of white women in underwear, that can tend to take a backseat; and maybe fair enough.”

After three decades exhibiting and working in Australia, you have recently made a global shift, working with Mother’s Tankstation, in Dublin, Ireland, for your European debut, and also a feature for Art Basel. How is the work being received?

Europe feels like a new audience, with its rich historical lineage of figurative painting. I enjoyed the work being viewed by fresh eyes. Political agendas can really take center stage in the art world and direct where opportunities and support are available. When it comes to images of white women in underwear, that can tend to take a backseat; and maybe fair enough. I’ve enjoyed working with Mother’s Tankstation and letting go of the reins, trusting their curation and direction. The Dublin gallery has a beautiful space with a skylight that suited my work.

You have won a host of Art prizes including the Len Fox Painting Award and the Doug Moran Portrait Prize, one of the richest prizes in the world. Does this grant some freedom from the rat race or do you still feel these same pressures?

I’ve won several Art Prizes, but this is not the same as institutional support. I like that the paintings speak for themselves, and that they have transcended my own life and geography, taking me outside of Australia. My work is able to be something and say something I cannot in the social world. They are a step ahead of me and my own consciousness. I have learnt to trust this unknowable part of myself that leaps into the unknown.

I’m independent and self-sustaining now. It’s been a long time coming. Because of the nature of my work, I am limited to producing five or six paintings a year, so that protects me from the pressure to be prolific. These days I try to focus on making good decisions about where I show the work.

The Wake, Oil on linen, 40” x 48”, 2018

Are you working on anything new at the moment?

For now, I’m back in the studio creating a new body of work following the recent exhibition in Dublin and the Paris Internationale Art Fair with Mother’s Tankstation.

This year, everything has shifted for me, personally and professionally. I'm getting to stretch myself out, and that’s not without its pain. I don’t know what’s ahead of me… and that is both a scary and exciting feeling.