Paco Pomet

The Surrealist Adventurer

Interview by Gwynned Vitello // Portrait by Lucia Rivas

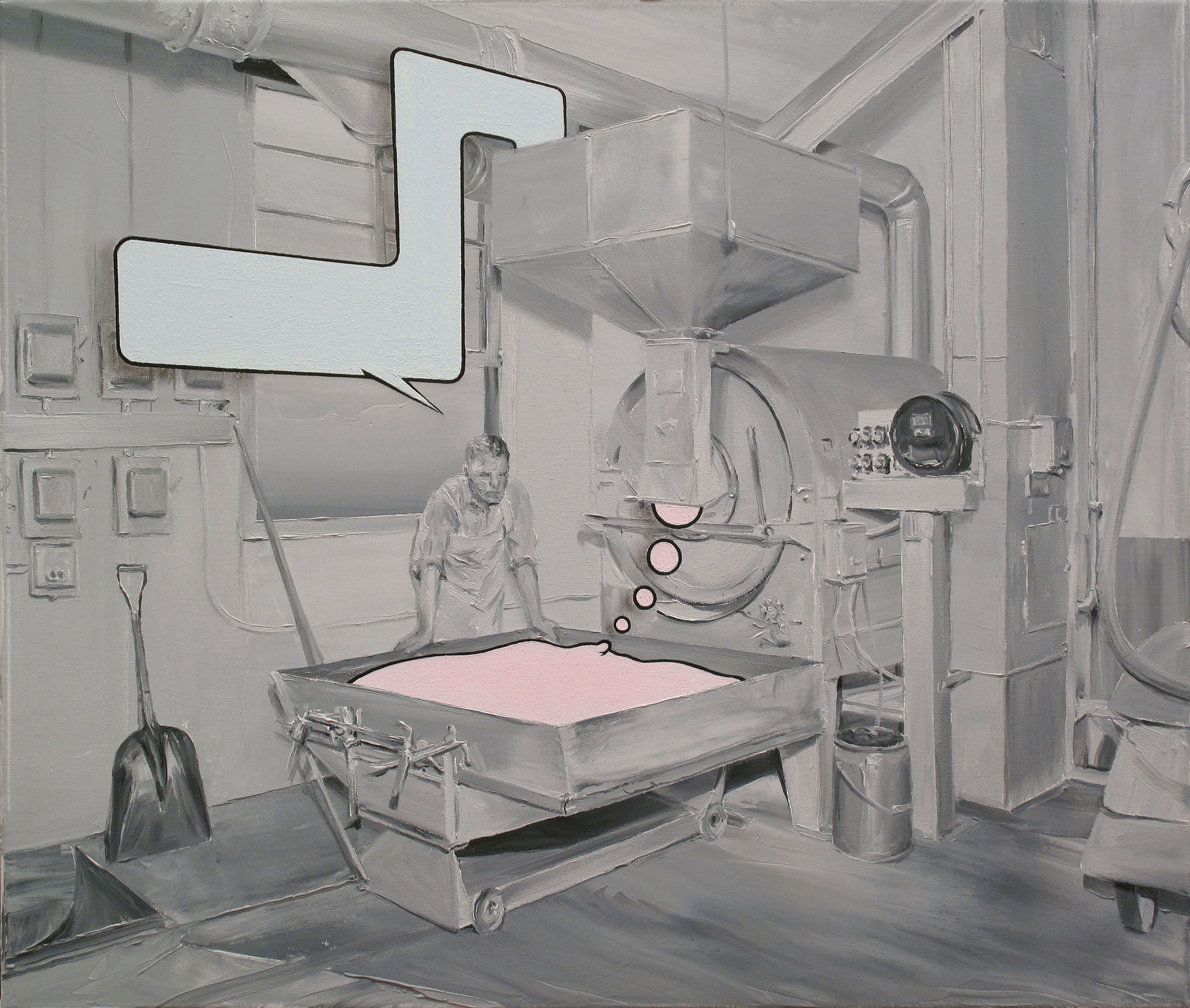

Viewing the Twilight Zone in black and white, as it was filmed, evokes simultaneous feelings of connection and distance, but you don’t just watch. The scenes linger and loop around with a searing shot, just like the paintings of Paco Pomet, who injects a jarring jolt of surprise or color into each seemingly serene image. Neither snack food nor stylized confection, this works like a time-released truth serum. A gash of crimson severs a glorious glacier. A poison pen suffuses a mountain lake. Somber faces engage (or are engaged) in incongruity. Something’s been happening, and things just aren’t what they appear to be. Educated at the University of Granada with further studies at New York’s School of Visual Art, Pomet combines the austere color and time elements of the Spanish cubists and the ironic dreaminess of the Andalusian surrealists. A conversation with the thoughtful artist reveals that, indeed, “You are about to enter another dimension.”

Gwynned Vitello: Given that the look of your painting is very singular, unlike almost any I’ve seen, I’d like to start off with you describing how you co-mingle the look of photography and painting, your actual process, including timeframe and materials used.

Paco Pomet: For quite some time, I have deliberately taken an open approach to photography as a rich, endless and reliable supply of motifs, a starting point from which an idea can arise and be turned into something else through painting. That dialogue between photography and painting turns out to be important in my work right now, mainly because I love realism. There are probably several reasons why I turned to photography: first of all, because only this medium can hold completely unseen fragments of the world, and because its enormous popularization has turned it into the container of a visual heritage that is practically infinite, in comparison with the rigid traditional structures of the genres of figurative painting. Secondly, unlike painting, photography, and even each individual photograph pictorially translated to the canvas—such is its power beyond its own medium, a feature of referential power and veracity of enormous value.

The age of the beginning of photography and cinema, a time period that comprises the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries, show us a time very enthusiastic about new inventions, a more naïve and intriguing time, before mercantilism and advertising flooded everything, The photographs that I like to recover from that era are a great source for my paintings. I am especially interested in documentary, press and amateur photography, including photographs done by myself purposely for a painting, and family photo collections. The more rushed or inexperienced the photographer, the greater is the photographic radical quality and distance from the visual and compositional codes of painting.

Once the image idea is generated and the visual sources or the resulting image are systematized, I draw the final image directly onto the canvas. When the composition is adjusted, I build up the image through oil paint. To keep myself concentrated on the paintings, I usually work in long sessions. I work on one painting from beginning to end, so the process doesn’t lose continuity, and also to maintain the fresh and malleable paint. Sometimes the applied paint needs to dry completely so a discordant color or an area with a different treatment can be added afterwards. Therefore, the process of some works can have different stages.

I imagine your artistic career gradually evolved into this method. When did you decide that you wanted to attend art school, and what was your style at that time?

Although this sounds commonplace for a painter, I began to draw like mad when I was very small. I was a shy, home loving child, perhaps a little introverted, and I spent hours looking at everything. My parents like to say that I’ve always been very observant, but the truth was that I couldn’t see very well and had to get glasses when I was five years old. I used to stare a lot and open my eyes wide just to distinguish things! When they finally got me glasses, I suddenly discovered the world was made in high definition, and I discovered textures, clean edges, dust and little reflections. I became fascinated with being able to distinguish infinite details and became trapped forever by the amazing variety of the visible. This rediscovery of things then led me to enjoy recreating them on white sheets of paper, and likewise, a fascination of the details appearing from the point of a pencil or pen.

Some years later, in school, the classic genres predominated and the discipline consisted of landscape, still life, or portrait. It was a boring, arid, Spartan period, but scared off the lazy imposters of the “calling.” It also served to build up in those of us that stayed on an ever-increasing desire for freedom.

To clean my head after those academic tutorials, I remember doing really crazy, surreal drawings between classes, letting my head and hand go. I remember trying to figure out how to draw absurd and mad ideas that friends proposed, laughing as I tried to manage how to accomplish those challenges. That was great training that served to give more confidence when approaching a problem on paper. There is still a residue from that time in my manner of drawing that brings solutions typical of comics and animated cartoons. After deciding to go to art college, I prepared for admission exams at the Fine Arts Faculty in Granada, so the academic training had to be revisited.

So many of your paintings, with their rural backgrounds, have an almost nostalgic feel. Did you grow up in that kind of setting?

Although I have never lived in the countryside. I had the chance to experience rural life from short vacations to my father’s hometown, a little village in Cordoba. I keep nice memories of that time, with sensations that form a very distinctive character. That raw and natural setting displayed in a different way, revealing peculiar sounds, lights, and even peculiar odors and textures, all of which formed a distinct landscape really different from the urban environment where I grew up. Sometimes I find myself being dragged by these memories and looking unconsciously for scenes and images that bring back those feelings. It’s not by chance that I moved away from the City years back and am now living in a village near Granada, where everything is more natural, relaxed and peaceful.

It’s clear you have a keen interest in the relationship of history and current affairs. Are you influenced by any particular historians or philosophers, or would you characterize yourself as more self-motivated?

My motivations come mainly from the everyday feeling of perplexity experienced when witnessing how the world insists on unfolding its meaningless features. As years go by, I find myself more and more misanthropic and skeptical. In any case, I won’t let this invade my spirit entirely, for I can always rely on the redemption of art. In my work, I can always lead a chaotic drift to a safer land of meaning.

As you point out, I am very interested in current affairs, but in order to fully understand today’s world, it is necessary to look back and examine historical events. Past is full of hints that can unveil the present, so in some ways, we could paraphrase that statement which says that there’s nothing new under the sun (Nihil novi). I have always thought that subjects and themes remain the same over centuries, and that human pursuits, aspirations and chimeras are cyclical. Nowadays, we might have different tools and ways of approaching those issues, but the important questions remain the same, even though the way they show up changes throughout the years. Technology accelerates and intensifies, but, for the moment, doesn’t add new meanings.

On a lighter note, how important were comics, television and movies in your work?

I remember being attracted to cinema and television since I was very little, like an average child. This attraction was reinforced, since my parents rejected buying a VHS recorder in the early ’80s when it was very popular. They considered that it would lead to watching too much TV. But this denial turned out to build an obsession, and by the time that refusal became unsustainable, my parents finally bought the recorder. I was hungry to see all the movies I could put my hands on, and my fascination for cinema lasts until today. I also loved going to the cinema, and I especially treasure great summer memories, both in my hometown and in a seaside village where my family spent vacations in August. Fundamental references were the Marx Brothers, Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, as well as adventure films from the ’50s and ’60s. Later on, I became fascinated with Bunuel, Fellini, Kurosawa, Truffaut, Bergman, Monty Python, David Lynch and Herzog, among others.

How does Spanish tradition play in your work? Is there an artistic reaction to the Franco regime?

In many ways, Spanish (Iberian) tradition tends to be more cynical, restrained, and especially more grotesque than Latin American art and literature. That said, I think my work is, in fact, rooted in many aspect of this tradition. The way I confront issues and themes in my paintings can’t avoid this Iberian tendency for a particular way of experiencing life, a disposition that has been strengthened by the tragic and hard events in the recent history of my country, especially when the Franco regime was in its cruelest period. Many scars remain from those dark years, and fatalism is an ingredient that is almost omnipresent in our culture; but sometimes humor represents the last and only resort to ride out hard issues.

Your integration of vintage photos with clues or signals of impending catastrophe is very unsettling, like when the air is still and sky is blue, but you know a storm is coming. Is your intention to ensnare the viewer and force them to take an active role?

I like how you expressed it. I like causing a reaction like this in the viewer and impelling him or her to go across the subject of a painting, and make their own decisions in ways to experience it. I think a good painting can sometimes work as a mirror and possesses the ability to return the viewer to the reflection of his own fears and desires. I still believe that a static image can achieve that. There’s a lot that can be said without appealing to irrefutable statements, taking the long way to address a matter instead of recurring to a direct—or, let's put it like this—a realistic approach.

Where do you find photographs, and how long have you collected them? Do you yourself take photographs?

Photography has fascinated me for a long time, and I have been collecting photographs for years. Any source can be interesting, and when I have the chance, I love to visit flea markets, where I have often found interesting pictures like family albums. The oldest ones are usually much more intriguing due to the changes in social habits that can be observed. Fantasizing about them and giving those images a chance to play a different task from the one from which they were taken is a thrilling feeling. I also take photos myself, especially when I am traveling, but also in my daily routine, and some serve as motifs for works.

Color plays such a dynamic part in your paintings. Do you ascribe particular qualities to certain hues? Do you have favorites to use in your work and some you personally like? How do you achieve that neon look?

I like to use color in a symbolic way, not as a describing tool. Sometimes the use of a particular tone is justified by certain attributes we apply to it, but it doesn’t always work in this way. Sometimes this unexpected use of color puts into question its properties and conventionalism associated with it; new and unexpected uses can bring a new set of ideas associated to the presence of a certain hue. In many of my works, this inclusion of a strong color breaks the monochromatic structure and creates a contrast heightening a specific element or area in the painting that needs to be emphasized. I tend to prefer saturated colors and I have a special predilection for red, orange or yellowish green, highly powerful tones that attract the gaze very radically.

The neon look you point out can be very effective. I am really fond of the ability that paint has to create an effect of real light, even though what I finally achieve is a delusion. Through this process, painting plays an illusionist role that I particularly enjoy.

Do you have any preferences where your paintings are hung or settings where they can be best appreciated?

To tell the truth, this is a question that I often let slide. Once the paintings leave my studio, in some way, I lose control of what happens to them afterwards. I should take more consideration deciding the installation of my works in shows, whether they take place in galleries fairs or museums, but I don’t always have the chance. Generally speaking, the setting for my paintings demands a special care, at least regarding illumination and enough space for the viewer to have a living space that puts away visual interferences.

There is so much humor in your work. Would you say that it speaks of cynicism or a way of coping, or making the best of a world situation?

Humor has always been present in my work, but it is a difficult genre, hard to hit the target. As time has passed and I have moved away from youth, skepticism and hopelessness have gained ground in the way I see the world. It is inevitable. I’ve always been an optimistic person, but this personal predisposition can be boycotted by the stubborn presence of reality. I happen to like realism precisely because I tend to be very observant, even though I’m more critical with reality. As a result, I think the humor in some of my work is somehow turned more bitter and caustic. A slight misanthropic drift has imbued many of my themes lately, however, a bright and clean humorous streak can appear dressed up in oil paint at any moment!

Maybe I’m romanticizing Spain, but during Europe’s economic upheavals, it seemed and seems to be especially buoyed by a national appreciation for food, family, walks in the plaza, to hold onto human values. True, or should I be more cynical?

You should definitely be more cynical! It is not a question of appreciation for values, but a resignation. As a consequence of the economic swindle (what governments usually call a crisis, using the easiest possible euphemism), many people have lost their jobs, even their house, and entire families had to return to their parents’ homes. On top of that, due to the State cutbacks in wages and pensions, those retired parents had to come with the drama of supporting their sons, daughters and grandchildren in a worse economic situation. There is no way out for people than to slow down or even stop their aspirations. Our current government is doing nothing about it, and it is really a big disgrace.

I think adaptability is a characteristic that describes Spaniards. The positive aspect means that we can enjoy the small and important things in life, as you point out, and reinvent ourselves. On the other hand, the negative angle is conformism. We sometimes adopt an attitude of watching life go by, as the title of a Spanish song, “Pasa la vida.”

But there’s nothing conforming about those elongated limbs you love to paint.

I would blame John Cleese and his wonderful sketch, “Ministry of Silly Walks” from the amazing series Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

Paco Pomet is currently working on two solo shows next year at galleries in Los Angeles and Copenhagen.