Nehemiah Cisneros

The Legend of the Wicked City

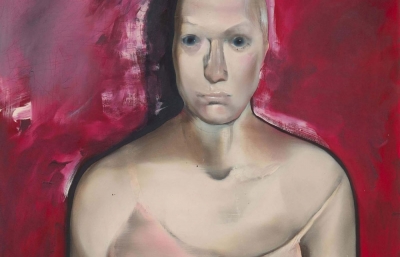

Interview by Evan Pricco // Portrait by Max Knight

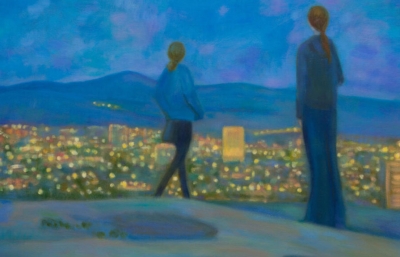

What captures you at first is the density of information. On each canvas, you are immersed in an imagination that is devouring every detail of the subconscious and attempting to make each painting an entire story of both place and person. It’s as if there won’t be another painting ever made in ode to Los Angeles ever again. It was van Gogh who once wrote, “I dream my painting, and I paint my dream.” In the case of Nehemiah Cisneros, he is painting his dreams and making us see what dreams can be. There is tragedy, romance, and history. A Cisneros painting is Shakespearian, and he is the maximalist director of this play.

On a sunny winter day, I visited Cisneros at the UCLA Graduate Art Studios, just as the night before he sent off his graduate thesis, and was surrounded by two massive works for his MFA show. I knew Cisneros for years as just AUGOR, the prolific, enigmatic, and comic-by-way-of-horror inspired graffiti artist who took over billboards in the same way he is now taking over canvases: with every attention to maximal detail. Like fellow MSK writers REVOK and POSE, Cisneros has transitioned his tenacity for graffiti into something with equal energy but studio-bound. Now working on a series he calls Wicked City, these monumental examinations of street life in Southern California are informed by both immersion and distance, a view of Los Angeles as a city with layers and characters that the Hollywood sheen does not reach. Wicked, as both a word of evil and surfer charm, is at play here, and we begin our conversation with dichotomy and balance.

Evan Pricco: Okay, so you are on the last legs of your MFA at UCLA. How are you feeling? What is sort of in the headspace of Nehemiah Cisneros right now?

Nehemiah Cisneros: Currently, we are in production on Wicked City—Milestone, my thesis exhibition, which features significant statements in my art practice while attending the University of California, Los Angeles, as a painting candidate at the Graduate School of Arts and Architecture. The exhibition features Wicked City 1 and 7, created in 2023, along with a suite of four works I am completing for the exhibit in the spring of 2024. I'm ecstatic about it.

What would you say, in the simplest terms, are some “significant statements in your art practice?” Give me an example of something you are trying to say with your work right now.

Wicked City documents a through line in cultural and class divides that connect via entertainment media consumption. I'm interested in presenting the viewer with the mundane, shown then erotic and traumatic, narrated through the blackest of humor. My paintings function as arranged marriages between contrasted iconography seamlessly illustrated through dense shape languages.

My current work in progress, Wicked City—Milestone, functions as my "Juicy.” According to what a track like "Juicy" represented for Notorious B.I.G.'s discography, among his many tracks about dope dealing and killing, Milestone stands firm as a redemption painting celebrating my candidacy to Master of Fine Art—a dedication to my mother, my guardian angel.

When I saw your paintings at the Rubell Museum in late 2023 during Miami Art Week, I had this sort of internal monologue of you as an MFA student, being a famous graffiti artist, having works in a museum, and finding yourself in Kansas City for your undergraduate degree. It has been such an adventure for you. Like a chaotic ride where you are just beginning to slow down. How much of all those things I listed make it into the paintings?

The four paintings the Rubell Museum acquired are Wicked City 2, 3, 4, and 5 for their Singular Views: Los Angeles exhibition. The works chronicle histories of iconic Los Angeles landscapes I call home. Home in Wicked City functions as a relic, the facade of a building with interchanging casts of characters. I look to the landscapes in Wicked City as a memorial, preserving my history as an artist.

Where is AUGOR, the graffiti artist, in your painting now? Is he in there? Do you let him in? Or is it just that you let the experience in?

When I think about the inspiration for my current work compared to my early work, I think about the aesthetics of biomorphic abstraction. The horror vacui is still prominent in the new paintings. The maximalist tendencies remain, with the composition as dense as possible. The design of framing a form within a graphic, bold contour, along with the vignette, is still prevalent.

Do you stay in tune with graffiti these days? I was thinking about some of your contemporaries and influences, from REVOK to Alex Pardee and ZES to other MSK artists, who have all gone in these exciting and different directions. Are you more tuned into that post-graffiti world, or do you also pay attention to billboards, tunnels, and freeway underpasses?

I moved back to Los Angeles shortly after the fright of the COVID-19 pandemic intersected with the George Floyd protests. The city was in a crime wave; hence, graffiti flourished, bursting through the cracked gravel of downtown Broadway streets like weeds. There are so many weeds growing now that I don't think the city has enough gardeners. Nonetheless, I'm in awe of vintage works by 1970s and 1980s subway artists like Quik. I often put on Style Wars while in the studio, along with movies from that golden era of Black exploitation films like Rudy Ray Moore's Petey Whiteshaw flick, where he plays the devil's son-in-law. The script is so absurd, so coded, and the costumes electric; the sets have a tethered patina that comes with small-budget film production. If I were to name someone contemporary, I do fawn over this person currently painting Funko-Pop characters as cholos around the city; they are cutesy and ironic, and if that wasn't the intention of the artist, it's even more genuine. I love seeing it.

You were born in LA and spent most of your life here, having found a voice at Santa Monica College in the mid-2010’s on sort of whim, would you say? I want to know about this pivotal time in your life, where you went from graffiti, SMC and then to the Kansas City Art Institute, where you began this new explosion of work.

I call Leimert Park, Los Angeles, home, along with a legacy of legendary artists like Timothy Washington, who was my neighbor during my residency there. Santa Monica College is a transfer school, a community of creatives with diverse practices, and the faculty and cohort led me to pursue my terminal degree as a fine artist. I felt comfortable making the type of work I wanted to hang on my walls. That mentality and the fortune of landing in new educational spaces with the same admirable faculty and cohort led me to earn my MFA degree at UCLA.

What has school taught you about art? Not just your own, but others, too.

Being a student of the arts has taught me that institutions do not accept the best artists; they take the best students. I'm fortunate to have experienced three versions of an education in the arts chronologically between 2016 and 2024. Studying painting within the studio restrictions of a community college differs from the immersive, cult like atmosphere of a private art college experience. Yet that also differs from studying art at a university that is the size of a small city. Graduating from UCLA bonds me to the bloodlines of John Baldessari and Charles Ray. My thesis committee, Rebecca Morris, Catherine Opie, Rodney McMillian, and Rodrigo Valenzuela, taught me to address myself as an artist, not solely a painter.

What did going to Kansas City teach you about your life in LA? Or maybe better put: what did time in Kansas City make you think of Los Angeles, and how were you able, from a distance, to create works about your hometown?

On an ethnic level, I drew parallels to the neighborhood nationalism shared between the Midwest's embrace of the Confederate flag and the gang-tagging scrawled throughout mid-city Los Angeles. My residency in Kansas City was between 2018 and 2021. I created an arc of paintings called Violent By Design in those three years. I refer to VBD as an arc of “ghetto mythologies” that straddle themes of urban fiction and satires of societal traumas through my renditions of art historical works from the 1500s and 1600s.

Through the lens of my Midwest cohort at KCAI, I saw my birthplace described in exotic ways and stereotypes, the same ways people from the coast would make hasty generalizations about Midwesterners. This back-and-forth of hearing opinions from two sides about one another spawned an archetypal portrait of society skinned blue and yellow, which still seeps into the current work.

Tell me more about Violent By Design. You are now working on a series, Wicked City, but V.B.D. seems to be where you really began to get your voice as a painter. What is the genesis, and was it something you had been thinking about, even if not creatively, for quite some time?

The name Violent By Design references the Jedi Mind Tricks album titled Violent By Design. This record was my soundtrack in the studio; I played it repeatedly while making the series. I created an arc of stand-out paintings, easily recognizable among my cohort at KCAI, by repeating blue and yellow-skinned figures Victorious and Villainous; the expansion of the V.B.D. universe played out in my head. How can V.B.D. exist as an animated series, fabricated statues, a playing card game, or a movie? Those thoughts kept my interest while painting many, many, many late nights at KCAI. The characters themselves are my renditions of Golliwogs. Instead of blackface characters, I empowered them, augmenting them with a blue color. Blue is endless. Blue is the ocean, the color of a superhero, and a power color. I've had a history with Jim Crow-era Black Americana due to growing up in my mother's antique store, "The Collectors Safari," in Inglewood, California, which sadly burned down during the Rodney King riots of 1992. The salvaged remnants of her collection of vintage Golliwog dolls relocated to my childhood bedroom after the fires turned to ash. I fell asleep to the glistening shine of the Golliwog doll's eyes until I moved out at age twenty. Like shark eyes loaded with the scars of my heritage, the lifeless doll eyes stared at me with a big red grin. I formed an atypical bond with trauma, but eventually, I started smiling back.

So then tell me more about Wicked City? Where is it? What is it? And how long can this series go?

Wicked City is a series of nine paintings so far. It is derived from the 1987 anime, Wicked City, which I chose because the name serves as a time-capsule for the era I was born in. Also, the name Wicked City is a double entendre. Wicked can mean something malevolent in addition to existing in the vernacular of Californian surf and skate culture from yesteryear.

The paintings have a shallow perspective like a stage play, nearly life-sized figurative paintings that function like Greco-Roman freezes. The compositions align with antiquated treasures like Pompeii's Villa of Mysteries, where a side-scrolling narrative unfolds.

I have no plans on ending the series; yet, I am in production on numerous outlier paintings that are not part of the Wicked City canon.

Okay, so Wicked City is a double-entendre of good and bad, birth and decay. In your thesis statement here at UCLA, you wrote something I really wanted to hone in on, how “Wicked City chronicles humanity unhinged. The role in the studio is that of a director; Wicked City is a stage play. The setting is the iconic backdrop of Los Angeles, a city in flux, where the natives grapple with preserving ever-distorting landmarks plagued with transplant migration or urban decay.” I want to talk about this idea of it being a play and you as the director. Because as a painter, you probably have an idea of what you want to paint, and then as the work develops, improvisation occurs. How much of these Wicked City works evolve in the process of making them?

I’m painting over all the faces in my current painting, I clash back and forth with my inspirations, applying realist painting techniques similar to Gustave Courbet along with an obsession with the crisp sticker-like line qualities of artists like Takashi Murakami. I had this grand idea to show the internal conflict of contrasting formal interests in the painting. I'm not struggling with it because this is not the first time I slugged it out with a painting in the studio. I often take photos of the work after leaving the studio to sit in bed Indian style on Procreate, digitally finishing the paintings in my pitch-black bedroom. I'm creating a guide for the next move to play the following day in the studio. I hope I have more time in future works to build the thinking processes out on the canvas where you can see more histories of the painting arguing with itself, but we are in thesis mode; as of this interview, I have less than twenty days to finish.

Are you thinking about theater or film as you make these works? It feels so cliche to ask that of a Los Angeles artist, but it’s hard not to think of film when you begin to put LA’s landscape and cast of characters into visuals.

I was vacationing in Bar Harbor, Maine, during the summer, which allotted time to read both volumes of The Directors' Voice, which logs multiple interviews with directors of stage plays and how they live their lives as artists. It was encouraging to share ideologies with creators who were not studio artists. I have since found myself daydreaming about the theater backdrop, the set props, and how I could connect with a director to collaborate on designing a play or co-writing a play myself. As for film, those intentions are there too, yet my cohort says my loglines for scripts might function better in an animated format.

I want to jump back a second. Your life as a graffiti writer and your life as a fine artist, too, are inspired by comics, animation, and skate graphics—just real, authentic visual culture that wasn't based on a fine art lexicon. I always thought you were the closest thing to an essential aesthetic of this magazine: where Robert Williams and graffiti collided. Did you find yourself a bit of an outcast with your inspirations once you got to art school, or are we so far past that at this point?

My favorite visual stimuli are from various subcultures and fandoms. I am currently working on a painting that cites furry culture; yet, it is subverting Manet's Olympia painting, where she has a "fursona." On the other hand, the picture plane is peppered with sassy Buldak ramen mascots. I am drawn to caricaturesque depictions of the figure, regardless of medium. I mostly pull from film these days, with lots of screenshots, and yes, the unapologetically imaginative works of Robert Williams have planted seeds in my formal desires since adolescence. Williams, along with artists like Jim Shaw, are what encouraged me to make large scale narrative paintings.

Maybe you don’t, but do you remember the first time you pulled something like this off? Like taking an element from subculture, art history, and say, popular culture like ramen and making work? It sort of takes real insight to get here.

While working as an illustrator with Upper Playground, I did a set of pieces portraying famous rappers in fantastic situations. The series mood board had the farty humor of Garbage Pail Kids' trading cards. I adopted it for the series, transforming Soulja Boy into a troll doll with a fluorescent pink gemstone in his belly button. "Trollja Boy Tellum," get it? I was 22; what can I say? That was in 2008, so it's been part of my practice for a while now.

In each of your paintings, you drop little clues, little autobiographical elements that only you and a close knit group of friends and family would understand. In the massive painting that was in your studio the other day, there was a nod to your mother and Mark Bode graffiti dropped in. Tell me about these elements you place on, well, often, on the bottom of your paintings—these little borders that contain so much information.

Consider each grouping of tiny figures to be a melody to the painting, a soundtrack. These figures provide depth, making the central figures appear totemic. When you pair smaller forms next to larger ones, they appear massive. My work applies contrasting strategies, whether scale shifts or contrast shifts, or dense patterning to void spaces, in order to slow down the viewer's read of the imagery and to dictate focal points.

You are part of the unique legacy of a group of Afro-Futurist and Pop Surrealist painters that have been given both new attention and deserved reexamination. I was even thinking about you the other day when Kerry James Marshall came up, and I was thinking about his comic work and the incredibly bold storytelling he does. But there is a great group of painters that have come from Afro-Futurist and Pop Surrealist aesthetics, and I wonder where you feel you fit in.

The current work aligns with movements like post-internet art and, to an extent, zombie figuration. I recently discovered the work of the Narrative Figurative movement in Paris, and I share the philosophies that artists like ERRO convey with the collaging of appropriated imagery.

Most work I see today, especially by artists younger than myself, seems to have some connection to the tropes of pop surrealism due to its timely references, collaging together of atypical imagery, and highly imaginative and ambitious Frankenstein paintings. I love it.

What's the part of finishing your MFA that excites you?

Earning my terminal degree excites me. It took all my life; I earned it.

What's the part of finishing your MFA that makes you nervous?

The mindset that something is finishing, I look at it as a beginning I am looking forward to. After eight years as a student of the arts, I will get to make work outside of a classroom setting, so that my work will no longer be helmed “student work.” That, to me, is more exciting than nerve-racking.

What was the last show or painting you saw that made you stop in your tracks?

The Hernan Bas show at the Bass Museum in Miami was the most inspirational exhibition I attended recently. We share multiple formal tendencies, which I would love to discuss in a studio visit one day.

If you were going to ask Hernan a question, what would it be? I see a similarity here.

I want to talk about lore. I want to compare the processes of information building and sourcing references. I love the themes of exploration and adventure in his works. I got an assignment in undergrad to draft covers for fictional science fiction novels, and I get that feeling of mystery and suspense novels from his paintings; I think about the Hardy Boys covers when I see his paintings.

I’m going to set the stage: When you were hitting billboards, sky high above Los Angeles and creating some of the most ingenious, detailed and original graffiti many had ever seen at such great heights, did you ever look down at the sprawl below you and start to create Wicked City in your head? Was there something about going out at night, finding the angles and vantage points few see, that helped inform these narrative paintings you are making now?

Man, it's hard to answer that. It's been so long since I have been in that headspace. I feel like the people, the fandom, want to read about those situations, yet my enthusiasm can only read those situations as anthropological. People do those things because they are not concerned with seeking adventure or seeing the city from a skyscraper; that's irrelevant. A real writer's only concern is to make themselves seen and to show everyone that they matter. That's what graffiti brings you: relevance. Graffiti is for the shy, the lonely, and the misunderstood; graffiti is a form of communication for those who lack the social cues of a normative society; they have connected to a fraternity of other damaged men—hurt men who are fatherless, black sheep, orphaned. I think about my painting On The Swarm, which has three versions of myself in different states of vulnerability; they are reaching out for one another to be consoled, held, and acknowledged together, and a bond forms, uniting a crew. It might be one of my most potent pieces. Maybe I’ll expand this series in the future.

Nehemiah's forthcoming solo exhibition with Josh Lilley Gallery will open in London in spring 2025. He will also feature in I’d Love to See You at Rusha & Co. in Los Angeles, opening on June 29, 2024. This interview was originally published in our SUMMER 2024 Quarterly.