Gifted and talented. No surprise there.

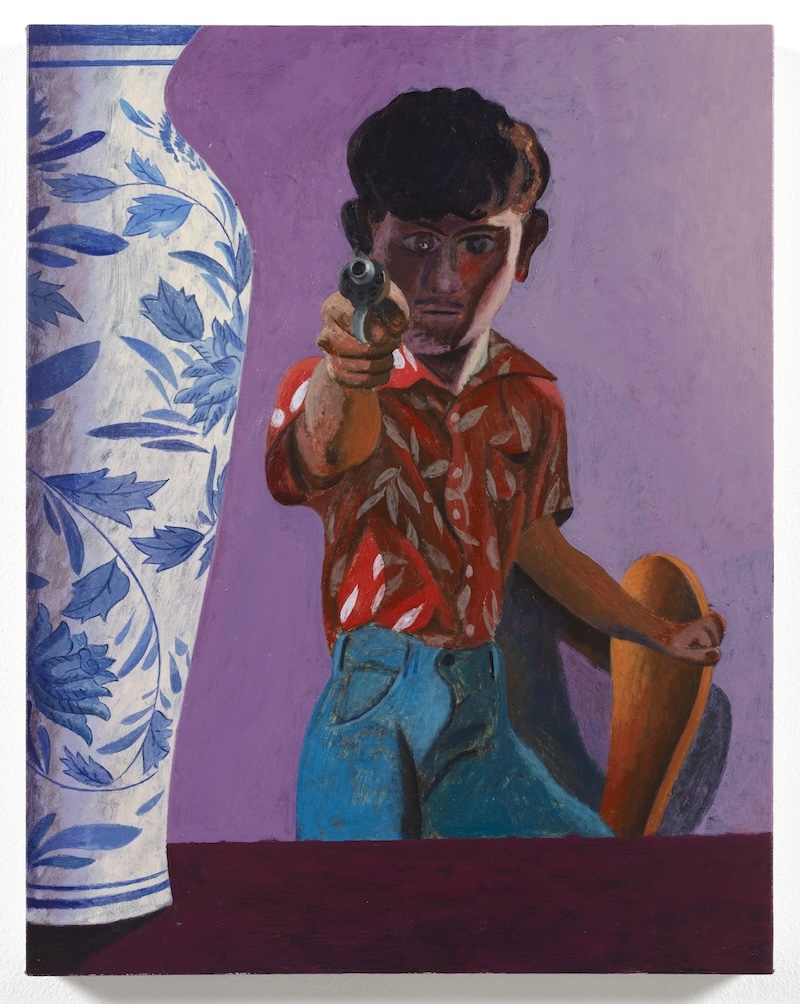

It’s silly. But it was rigorous, morning to night every day, and because of those long hours in school and hanging out with boys for years, that was my life. I was exposed to all their behaviors. They are rascal creatures, they mostly do horrible, mischievous things and sometimes nice things.

I also identify as a man and boy myself, it’s something I relate to. I think all problems or issues in life involve men. I personally have more problems with men in terms of daily interactions. I don’t have that with women. I see women in harmony, as perfect human beings, everything goes smoothly, no problem. When it comes to men, it’s difficult because I’m part of that group myself, and I know where many of their issues come from, so it interests me.

Growing up in Iran, I was also exposed to western cinema through national TV. You may be able to imagine that under a completely ideological political system, there was so much censorship. We thought we’d seen the full movie, but we didn’t know some scenes—and in some cases, an entire character—were edited out, mainly females, because of the way they were dressed.

My introduction to the world of cinema was those classic movies by Orson Wells, Antonioni, Tarkovsky, and other directors in that caliber; partially due to censorship and partially because of the nature of those movies. I was watching great movies mainly about these complex male characters, although they were probably not appropriate for a teenager.

I feel lucky I got to see these great movies, back in the ’80s and ’90s, during and after the Iran-Iraq war. Everything was limited. We had two channels and there was not much money to produce Iranian films. Now, it’s completely different, like the rest of the world, but back then, they mainly used their archive from the pre-Revolution era, when the previous regime was investing lots of money to collect western movies.

Did you start making art as a child, and how did it change when you left Iran?

It’s like that cliché that every kid draws and paints, but I just never stopped. I didn’t go to any art classes, I would just copy things from books. Later on, my dad had an amateur artist friend who gave me lessons and introduced me to western art history.

I was drawing until I went to an art university that was supposedly the best in Iran, but I wanted to learn anatomy like the old masters, and that’s not what they teach in Iranian art colleges and universities, for obvious reasons. They couldn’t have nude models.

Everyone was pushed into abstraction and I was never interested in it back then. I dropped out after a year, and later came to the US for college and grad school when I was 26.