Michael Kagan

Trust The Universe

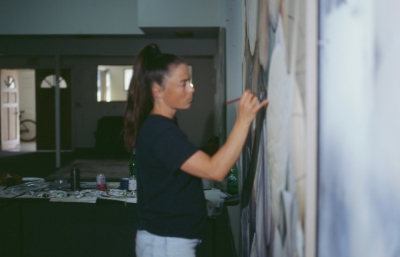

Interview by Sasha Bogojev and portrait by Jon Brown

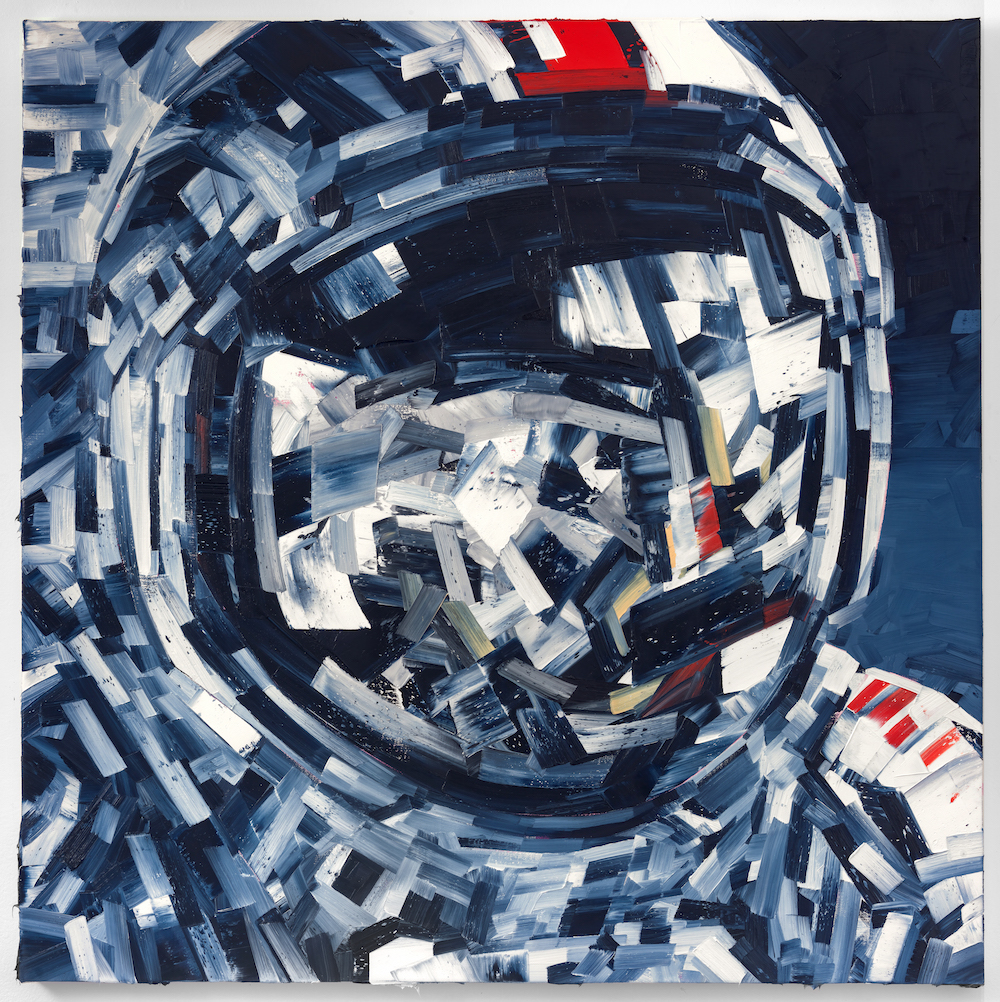

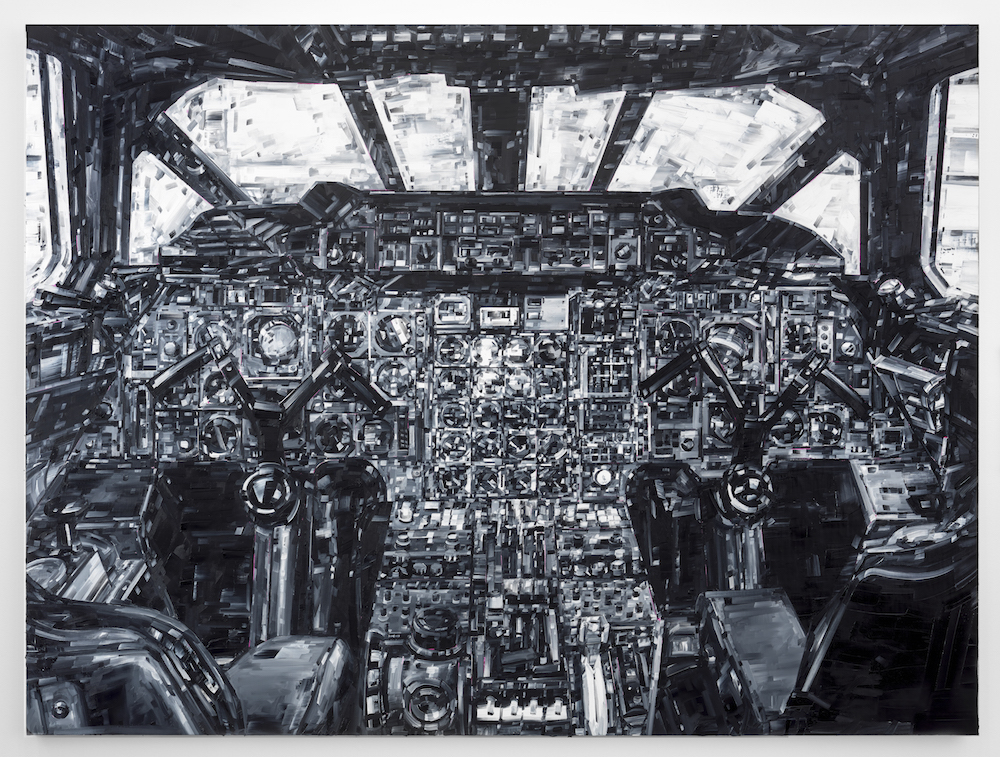

"Work by an academic painter," sure doesn’t summon images of astronauts, airplane cockpits, or rocket launchers. Yet, those are precisely the motifs that escalate New York Academy of Art MFA graduate, Michael Kagan. Blending his love for painting with personal interests, he gradually shifted his practice towards people, machines, and moments that celebrate the strength and determination of the human spirit. Just as his subjects ascend beyond the horizon, he pushes the boundaries of painting as a medium by constructing images from shards and slashes of expressive, abstract brush strokes.

After years of successful solo shows around the country, international recognition, and collaborations with such brands as Pharell's Billionaire Boys Club, Kagan is about to present his first institutional exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art. He will simultaneously release a monograph book and launch 2020 with an international debut at Hong Kong's Over The Influence. The timing couldn't be better to finally sit with Michael Kagan and talk about the relationship between space exploration and brush strokes.

Sasha Bogojev: What always strikes me about your work is this almost sterile technique because of your motifs, but there is an obviously strong painterly process guiding your practice.

Michael Kagan: I see what you're getting at. When I'm not painting, exercising or doing something, I'm thinking about the evolution of the work. So, the painters that I'm attracted to, that I've always been attracted to, are the ones who have this kind of natural voice or technique. It doesn't matter what the technique is, as long as it's not being forced. It's like the way people dress, it just happens. You can tell when people are faking it and when people aren't. I've always kind of believed that with my work, I just wanted it to be like a natural process. When I started painting astronauts, I think that's when my technique came together. I was doing a lot of figurative painting, but I was doing these thick squeegee brush marks, and I always wanted to use a lot of paint, but not flesh-colored skin and these big figures. Then, one day in 2006, I decided I wanted to try to do an astronaut painting, mainly because I knew a lot about it from growing up.

I thought I knew a lot about it, so I didn't feel like I was faking the imagery, and it felt genuine. And then I thought the brushstrokes translated nicely to it, these kind of short brushstrokes. Looking back on some of my work, there was this flow and these circular strokes, and these paint splatters, and now I work in these shorter block stripes. But I kind of like that it's happened naturally. It wasn't as if one day I said, "Oh, I'm going to shorten my strokes." I feel like my paintings have more detail and more information, there's more busyness to them now.

There's a weaving of strokes, but it was something that just kind of happened naturally, which, I think, is kind of nice. I like that when I see other painters that I admire, whether Jonas Wood, Luc Tuymans, Richter or Christopher Wool, there's this flow to their work, but then there's this organic progression of how it evolves. It's not super jumpy with how it goes.

From my conversations with artists, unforeseen circumstance end up being breakthrough moments, because otherwise, if you are confined to a certain schedule of catching up with deadlines, you become almost like a craftsman.

Exactly, as much I love to be the studio, it's also good to get out because I think that's when I really process what I'm working on. It's the power of saying no, too. I think it's important to say no to some things. If a subject matter is a demand, or someone comes through with a show idea, but you feel it's not a good fit because you want to start moving your work in a different direction, I think it's important to also back up and say no, take the work this way.

This year feels like all things are coming together: these two big shows, the monograph... How does it feel to have all of this happening at once?

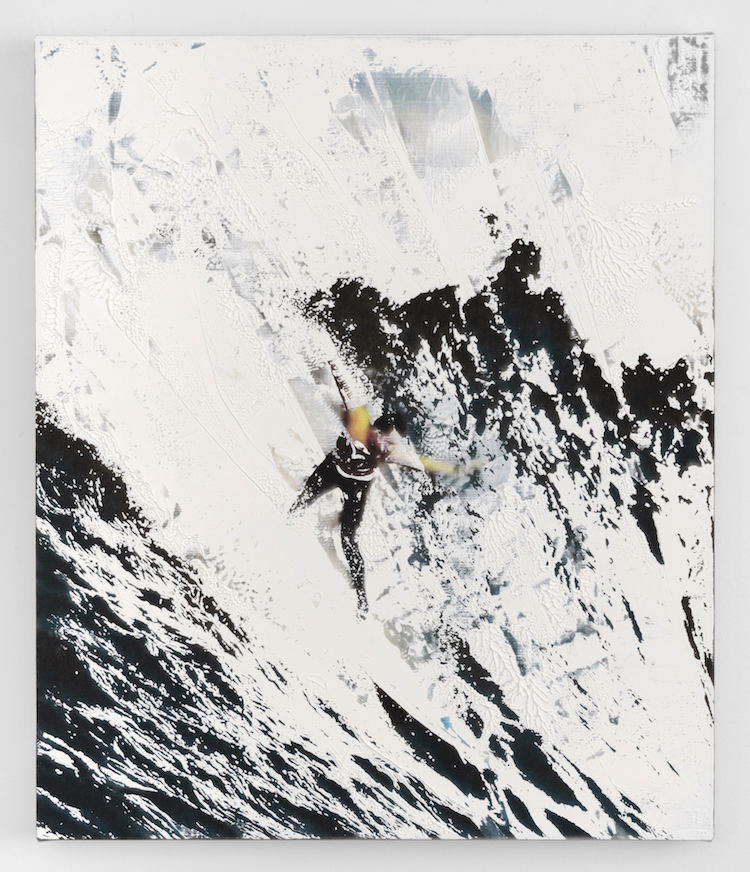

I mean, it's funny, when I did this painting of Everest in 2016, it was this big painting. Some of these paintings just flow super nice, and some are epic battles in the studio. They're usually successful, but some of the ones you have to fight through are the kind you love more in the end. As you know, the struggle that you had made it so. My wife once came into the studio and saw me obsessing about the painting and taking photos on my phone and going through to see what I can fix, and she's like, "Just trust the universe, just trust the universe, everything has a flow, you‘ve got to trust the universe." And then I named the painting Trust The Universe.

So when did you start working on this museum show?

The museum show was in the works for almost three years. There were timelines set up and then they’re also doing a book. I got Todd Bradway on board, who has done some really amazing work with different monographs, and then I started working with OTI in the last year, and they want me to come to Hong Kong in March because that's the best month. So I feel like the timing worked out well because OTI's really behind me with the book and the museum show. The museum show will be great and then there'll be this other nice show afterward.

I like that I didn't approach the museum and ask them for the show. I've always known the museum from growing up there, and they came to do a studio visit three years ago. I always like the dealers and collectors who do the studio visits, and then you think they're going to offer you something, and they say, “See you next time,” and they do another studio visit. So they took their time before asking me, which I respect. They didn't just hand it over. I'm from Virginia, and a museum show is important for any artist's career.

Even by itself, this book sounds like it's gonna be something else.

One of the reasons I asked Todd to come on board was because I didn't realize the book had so many details. With Todd and I kind of taking it to the next level, we took another step getting Pharrell to write the forward. Bill Powers, who has interviewed some really great artists, did the interview in the book. Matthew Israel, who works as a curator for Artsy, is going to write the essay. I've known Pharrell for years, being from the same hometown, and I've done two collabs with Billionaire Boys Club, and am doing another one this summer. I went to KAWS’ show in Hong Kong and I ran into Pharrell, and he didn't know I was going to be there, so he's like, "Hey, what's going on," and I told him about the book. He's said, "I'd love to be involved in any way that's possible." I suggested the foreword and he said he’d be honored. It's cool that there’s a nice flow.

I like that my first museum show will be in Virginia and it's nice that Pharrell's from Virginia and he's going to write the foreword to it. He gets it. One big boost in my career in 2013 was my collaboration with him, which helped move things in a good direction, so I like that he's coming back to help with this book.

I think the title of this interview might be “Trust The Universe” as well. Is the museum show a retrospective, or are you making new pieces, or is it a mix of things?

It's kind of a mix. There were talks about making a small new body of work and just showing that, and there was an idea of just focusing on one subject matter and getting those paired. Then we decided to make it kind of like a mini-retrospective of the past eight years of work. But also, I've painted mountains, surfers, astronauts, rockets, and cockpits, so we decided to kind of focus in a little bit on what has gotten me to this point, which has been the big cockpit paintings, the big astronauts and the rocket launcher. So we're focusing on those three things. And some F1 drivers, I forgot to mention.

We're getting back the best of the best work. As we're doing that, I'm kind of seeing that some of my best collectors actually have the best work too. So we'll get paintings back from Japan and Europe, and then some great collectors who have recently purchased my work will be behind the show. It's nice to see the work again. Then there are one or two new paintings I'm going to make specifically for the show that I'm working on this summer.

Now that you've named your themes and motifs, I remembered that before I ever saw your work in person, I always saw these brush patches as digital glitches of images. Was that your aim?

No. I've gotten that before a couple of times. It's one of those things that I don't see but other people point out, and then I can understand how they see it. I think it was actually Eric Fischl who said, “Oh, what kind of filter are you using in Photoshop for your reference image?” But that's just the way my mind breaks up the image.

I had a big cockpit painting at OTI in LA and it was the cockpit of the stealth bomber. When I was at the opening, some woman wondered if it was an aerial cityscape. And I said, “No, it's a cockpit.” And then she's like, “Okay, I see the cockpit,” but it wasn't clicking for her. Depending on how close you are to the painting, it can read one way, or it can completely fall apart and not read.

So do you build your work like that, with the purpose of achieving a balance between representational and abstract?

I mean, that's something I'm always trying to do with my brushstrokes too, and we're playing with that idea in the book. We have these super close details on some pages where it just looks like an abstract painting, full bleed on the page. Then when my paintings are shrunk to book size, they achieve a photographic quality. But when you see my painting in person, when you're up close, it's just these chunky abstract sections, and then when you back away, it kind of tightens up.

I like that my paintings have that play because one of my favorite painters is Tuymans, and I love how his works are just quick reads, just like a snapshot. So I'll use the analogy of how, at a crowded opening, when you're just kind of peaking over people to see the paintings, you can immediately get what it is. You don't have to walk up close. You'll just get the image. And I like that my paintings can be like that. I like that you can just be like, boom, astronaut, even if you just silhouette the figure in most of my things. Boom, rocket! I like that they are kind of these static quick snapshots, but then you can really get in and see a flurry of strokes that, if cut into a little three-by-three-inch section, would be like a little abstract painting. That's the way I'm building them up when I paint them. I'm just making these little abstract paintings in little three or four-inch sections, and then it all comes together.

Since you reference abstract, do you have an interest in making that kind of work scaled up?

I mean, it's like the thing I said when we were talking before, in the beginning—it is if something happens naturally, unforced. In my recent show in Miami, I did these squeegee rocket paintings, and some really read as a rocket, and then some are just one squeegee stroke. If you hung one of those rocket paintings in a group show, it might possibly look like an abstract painting. So it is an abstract painting. But if you hung it next to an astronaut painting, in one of my solo shows, it would read as a rocket. The same thing happens with some of my surfer paintings.

I want to ask you about your personal connection with all this, let's say, technical stuff. Astronauts, rockets, cockpits? Is it like a childhood interest of yours, or is there more history?

Bill Powers from Half Gallery and I got into this when we were talking last week, which was good because it's always better to talk it out. You get into more ideas. When I grew up, my father was really into NASA and its history. He remembered the moon landing and all that. He knew the history, so we would watch the movie The Right Stuff, and we went to Space Camp together. He had telescopes and would show me all that. So, when I made the paintings, the astronaut things, I knew a lot about it. But I always feel like the astronaut paintings have a core structure in the middle, and then it's the core idea that got this body of work moving, so everything else spirals out of it.

What fascinates you regarding this technical stuff?

I'm fascinated with the idea of the Concorde, of this supersonic flight. I did this painting, which will be in the museum show, called Concorde, and it is a black-and-white painting of the cockpit. I like this idea of supersonic flight. A lot of these moments are things that people have never done before, people doing things, whether it be big wave surfing, or F1 drivers pulling serious g-forces. I like that all these people have been the first. These surfers, drivers and all of them doing death-defying acts, and astronauts doing it for the greater good of civilization—these astronauts, the first men on the moon, The Mercury guys, the Gemini guys, and the Apollo guys were the first to make a mark in their fields. But it will continue to be harder to be the first at something as civilization goes on. Everyone has a different motivation, but they're also doing it for themselves, and I like that all these people are doing it for that moment. The guys that climb Everest or K2, they're all on the summit for not even a couple minutes. Then they come down, but they have that moment when it was all worthwhile. If they died trying, it would be worth it, and that's in the paintings too. The painting gets a little macho with this kind of hardcore stuff, climbing, F1, rockets, but I like that drive behind it.

Do you know what you'll be making for the Hong Kong show with OTI? Is it gonna be along those lines?

For my show in Hong Kong, I'm starting to work on a few paintings, and I'm doing some more F1 stuff. I have only done four or five F1s, but I feel like I didn't really go for it the way I was capable of. And now I'm painting better than ever, so there's a bunch of imagery that I would love to work with. I've been making a lot of black-and-white paintings recently, very subdued, color-wise. But with the F1 stuff, I'm going to go full color with that Ferrari red, and that really chromatic yellow. It's kind of like I'm going to dip back into the figurative stuff because when the visors are up, their eyes show, and then some guys hold onto their helmets. So, very slowly, I’m going to reveal the figure once again.