Matthew Palladino

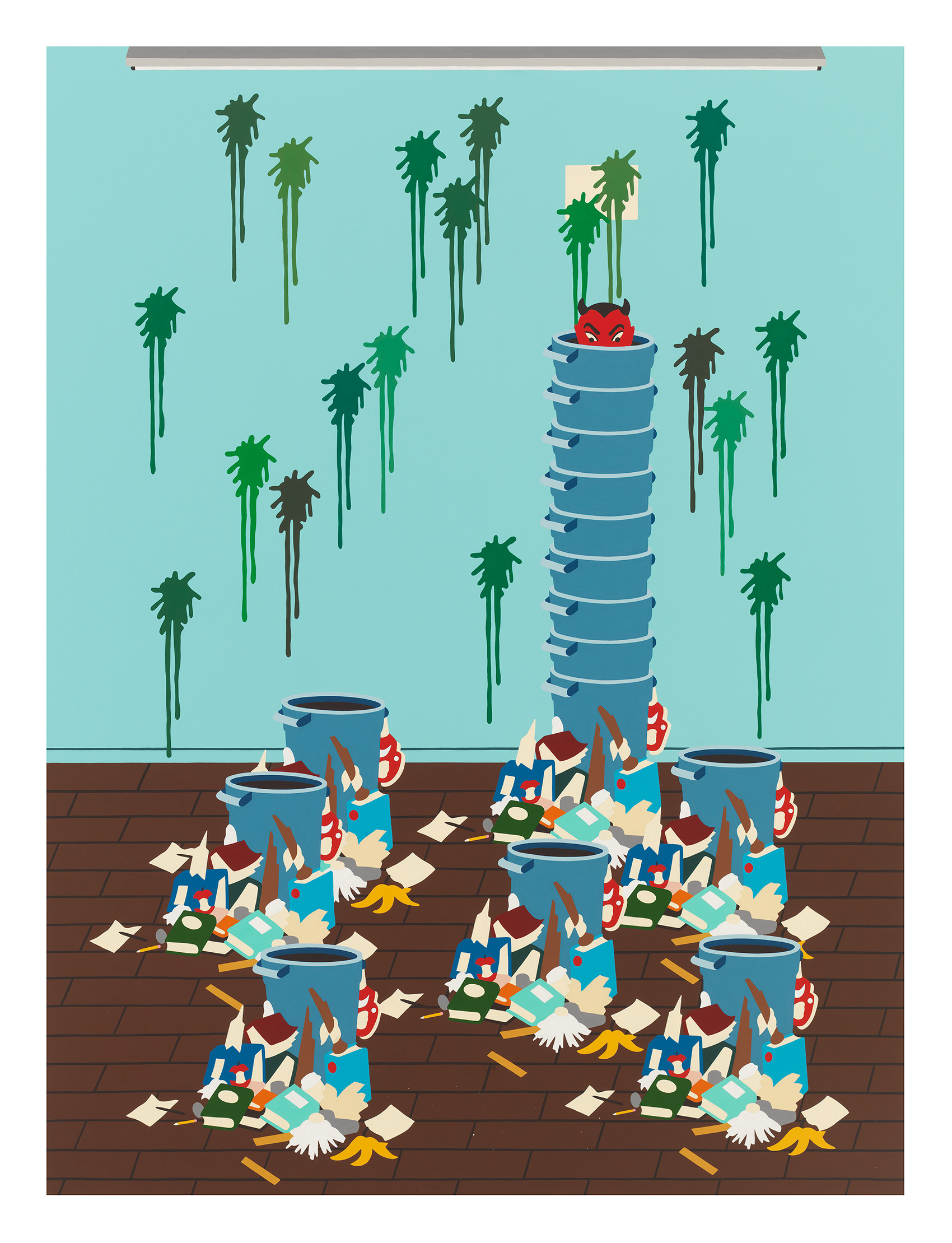

The Haunted Playhouse

Interview by Gabe Scott // Portrait by Clark Mizon

The work of Matthew Palladino has been undergoing a cyclical evolution over the last few years, as his painting and relief sculpture have engaged in a binary orbit around each other. Much ado has been made of his pop-drenched, three-dimensional creations that regularly parody reality, both in content, as well as portrayal in their medium. The outcome of his blurred boundary feels akin to being stuck in a Duchampian vacuum; an objective sensibility is questioned through a series of manipulated readymades, steeped in irony and a deviant sense of humor. In advance of his upcoming solo show in Hong Kong on October 19 at Aishonanzuka Gallery, we discuss the process of permutation, some roots of his visual syntax and how creative exploration can come full circle.

Gabe Scott: Give me some examples of early graphic archetypes that have held longstanding influence and that you may hold crucial to the tenants of your own conceptual design?

Matthew Palladino: It probably all started with Pee-wee. That was definitely my first real obsession when I was around four or five. The elements of that show, the playfulness, color, humor and weirdness, that influence seems to still linger. Cartoons and animation were the main delivery system for humor and visuals growing up. My dad used to take me to the Spike and Mike’s Twisted Festival of Animation. I was probably a little too young for some of the content, but I loved it. It was interesting because I think I saw some early Nickelodeon cartoons before they were on air at those festivals, and then when we got cable, there they were, right in your home. MTV also had a lot of weird adult-themed animation, Aeon Flux, The Head. It all made an impression on me. I loved comic strips; Calvin and Hobbes, The Far Side. I remember stealing Matt Groening’s Life In Hell from some older kid’s cubby at school when I was eight or nine, and taking it home and obsessing over that.

I never gravitated towards the classic superhero-type comic books. But I would go to this comic book store around the corner from our apartment in San Francisco, Comix Experience (it's still there!), and they would have these bundles of ten comic books for five dollars or something. In those bundles would be a variety of all sorts of funky stuff, a lot of Mad magazines from the late ’70s and ’80s, as well as Sergio Aragone’s Groo The Wanderer, which I collected, probably the closest thing to a superhero I ever got into (his superpower was that he was an incredibly deadly moron).

I found a Rat Fink comic in one of those bundles and that got me into Ed "Big Daddy" Roth, and eventually, the custom car culture of the 1950s, early ’60s in California. I was really into drawing my own custom cars for a while, as well as aping my own versions of the motorcycles from Akira. But then I took a summer class when I was like 13 on car design, and the instructor on the first day gave this speech about how none of us were going to be designing the next Ford Mustang and that we should forget about designing cars. That turned me off to the whole thing. But I think the colors and forms of the custom car stuff had a big influence on the relief work I made later.

Growing up in San Francisco and primarily around the Haight Ashbury, psychedelic art has had an influence. I don't remember being specifically interested in it, but people have brought up the "trippy" look of some of my art so I think that aesthetic just seeped into my subconscious over the years. That and drugs.

What about the early murals, characters and wall works you were doing around SF?

High school was all about graffiti. Letters weren't my strong point, but I was okay at characters. Spray paint cans as the angel and devil, sad sack faces, that kind of stuff. That was my first experience of art as a social act. It came with a kind of community, and gave me some sense of the value of making images for not just myself but for others to see. I discovered Barry McGee's art, and from him I got into Margaret Kilgallen and Chris Johanson, along with a lot of other great artists from the San Francisco art scene. Their work formed a bridge from graffiti to more personal "fine art" for me.

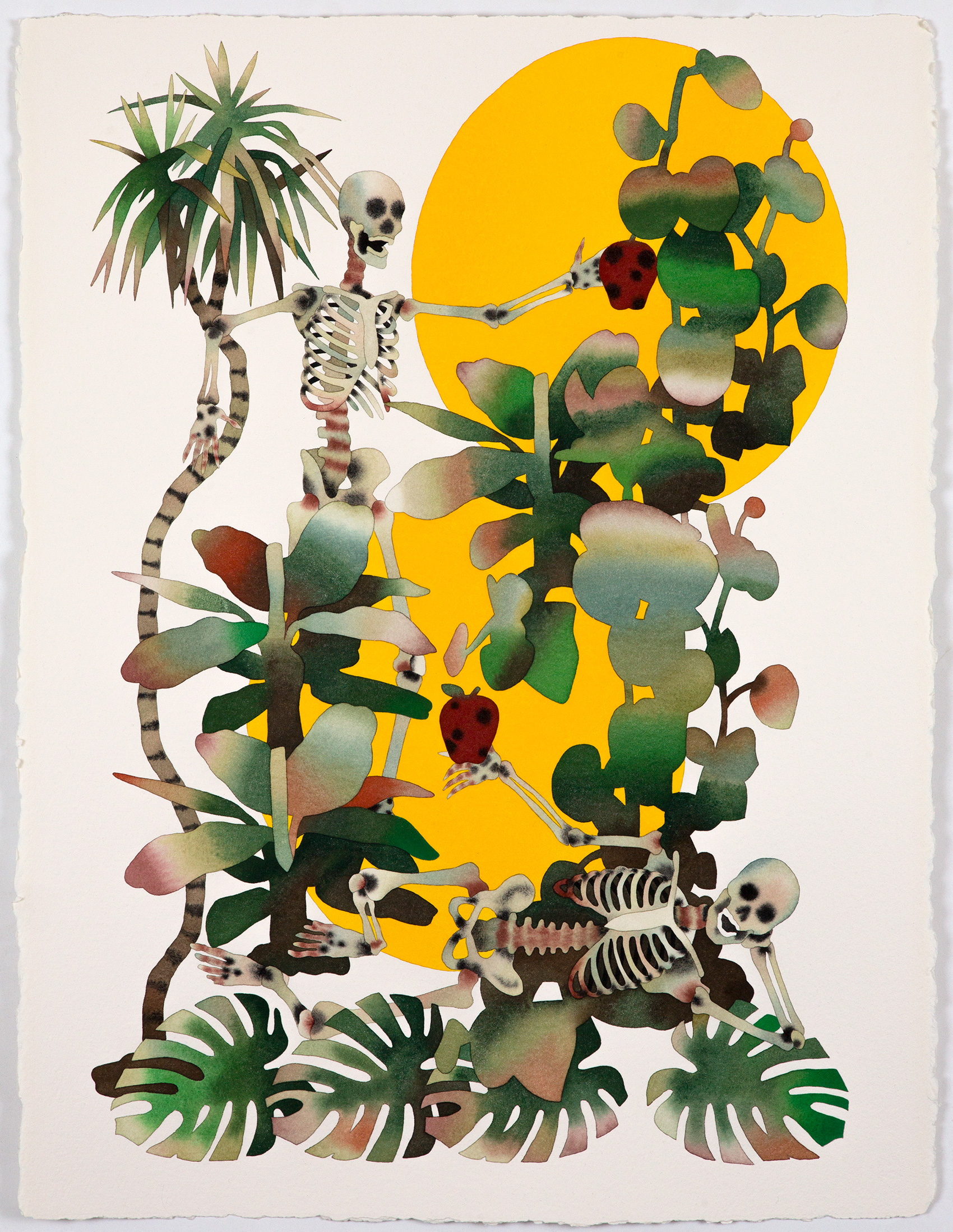

How did you end up gravitating towards watercolor? It’s a starkly different media than aerosol?I went to college at CCA in Oakland and ended up taking a watercolor class. I had never been interested in traditional painting. I’m not sure why, but realistic rendering, brush strokes, acrylic paint, even canvas, all those materials were such a turn-off for me. But watercolor felt completely different; the immediacy and permanence of it, the delicacy of the materials. It has a bit of a mind of its own. You can guide it but you can never truly control it.

You mentioned the elements of Pee-wee's Playhouse and Matt Groening’s Life In Hell, particularly the darker adult themes, as an initial and lasting influence. How would you describe or explain the pervasive subterfuge in some of your works that tow a line between a black humor and donut sprinkles?

The darker content is usually influenced by a mix of current and historical events. I don't start with the mindset that I'm going to make a piece dark. I think it all gets consumed then expelled through the work. In an attempt to gain a deeper understanding of people, I try to observe their actions at their worst as well as their best. There are hard truths in there. I feel myself having to sit with it a while, trying to put myself in the mind of the offender and the victim. But if you spend too much time there, it starts to eat away at you. So then I try to untangle it from my consciousness, which making art helps to do. The darker stuff I try to be careful with, especially when dealing in real life events. My hope is I’m respectful when going down these ugly rabbit holes. They’re not my stories, and these things really happened to people, so I try not to get too emotionally self indulgent or fetishistic. But something about it draws me in, and that’s the cycle that ensues.

The Gilgo Beach piece is definitely one of my favorites, but also one of the most unique paintings you’ve done—it has a completely different feel than so many of your other works. There’s a darkness to it that goes far beyond the story presented in the media, and your depiction of the scene. Tell me about your personal fascination with the mythology that has been constructed around the story and how that folklore prompted you to work in somewhat of a different motif.

Yeah, the darkness comes into the work and hangs over it like a cloud sometimes. The insanity and evil of men seems to be a recurring theme. I think that first popped up when I saw the documentary Jonestown: The Life and Death of People’s Temple.

That had a profound effect on me that got worked out in the paintings. It was just such a crushing feeling, the hope and positivity of the congregation of that church and their ultimate murder at the direction of a sick man. It haunted me. That darkness that lies in men, you worry that you have that in you somewhere, and it scares me.

With the Gilgo Beach painting, that was actually about a very specific feeling. It was the loneliness of those bones, sitting out in the brush, discarded and alone, night after night. It felt cold and dark. I felt like those bones, and I wanted to expunge it. After watching a documentary about the victims of the Long Island serial killer, I was haunted by the thought of their remains, laying out exposed and alone in the brush night after night, waiting to be found. That sad feeling of loneliness followed me around until it made its way into one of the paintings. I think that piece was less about the violence these people had experienced and more about how they had been used and discarded. The lack of any justice or conclusion as to who had done this to them compounded that feeling and left it open to fester.

How have you come to organize and manage the graphic imagery that you've utilized, both from personal experience and from a larger cache of pop culture? in other words, what caused you to see and create the picture plane in the manner you do?

Working on the computer has of course impacted how my images are organized and built. Almost everything I do is initially "sketched" there. I like the modular aspect of making images on the computer—gathering together images and building them up on the picture plane, editing them, taking elements out, rearranging, until you think you've hit the right balance. I like that my hand is not involved in the planning because the hand has a mind of its own, and I found that when I hand-sketched things, while I enjoyed that tactile experience, it was too influenced by what felt good to do, which worked against what I would be trying to accomplish. So using the computer broke me of a lot of bad drawing habits.

I think growing up consuming so much visual information through screens from such an early age, it was inevitable that its influence would have some effect on fine arts. Computer programs such as "Kid Pix" (which was like MS Paint but with sound effects and little animations) made the computer an appealing tool for creativity when I was young. But while I usually start my initial planning on the computer, I think it’s important to take it out of that space and bring the final creation into real life. You're locked into the programmer’s world they've created when using their software, so I like to make my work by hand for the final stage to have the freedom to make choices in real space. The computer is just one of many tools I use. It’s not my preferred space for the image or object to live in or be consumed.

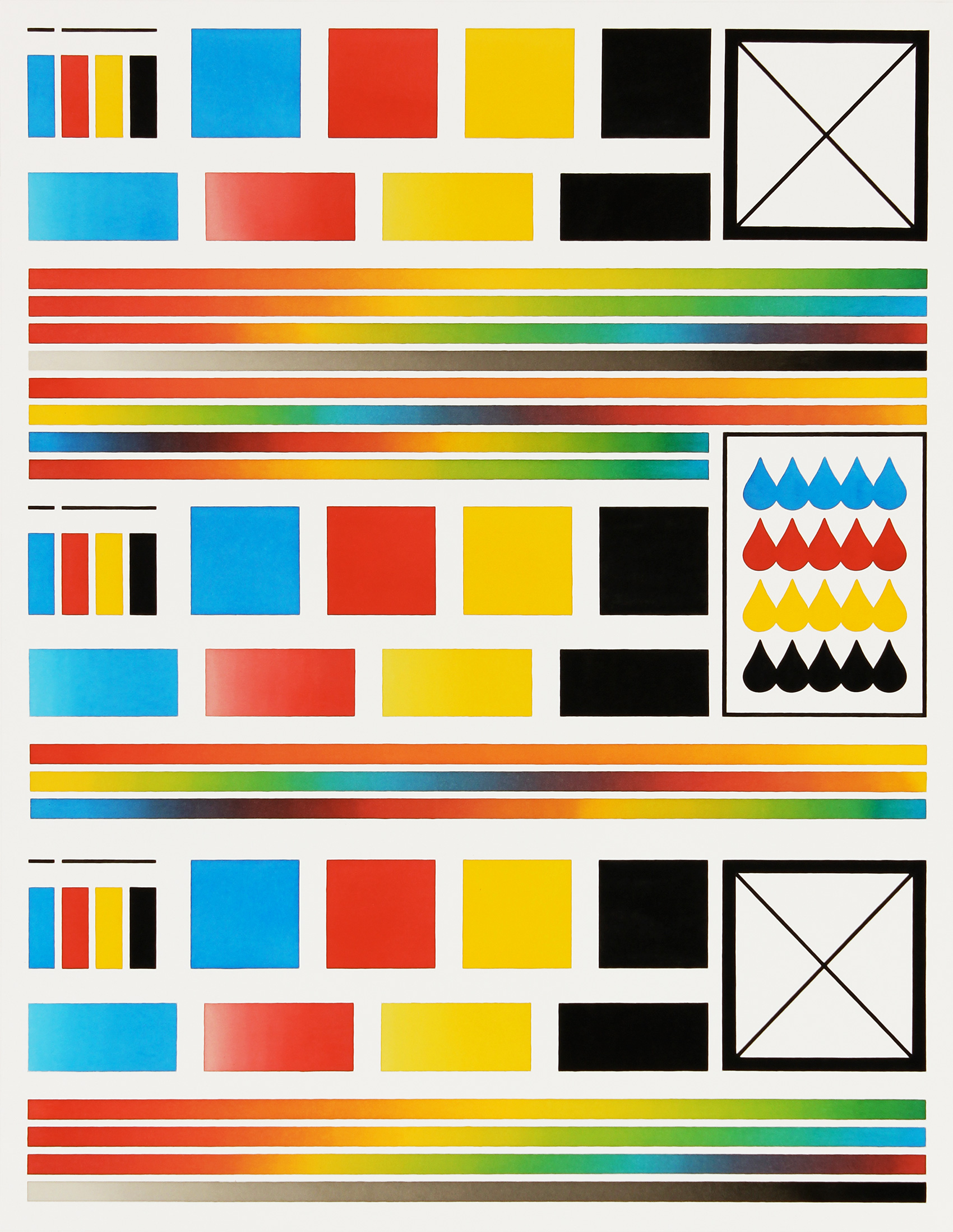

I have this clear memory of when we got our first inkjet printer, printing out clip art, and specifically this red Ferrari, watching the printer head go slowly back and forth, and it coming out so perfect. I had this distinct feeling of jealousy. I wanted to be able to do that. I think that was the beginning of a long relationship with using and battling the computer in making art. I even did a painting about it, Test Print (John Henry) where I tried to perfectly recreate in watercolor one of those test prints you do on your printer to make sure everything is calibrated. It made me think of the American folk tale of John Henry battling the steam engine for his job. But it was tongue-in-cheek since I’m just some ding-dong with a paint brush and I don't die in the end.

What was it that compelled you to start working with the plaster reliefs? Was there a certain rendering within your painting that prompted the shift?

I think is was around 2011. I was living in Philadelphia. I had some success with the work on paper but felt like I was getting to the limits of what I could do in that medium. The early watercolors are painted incredibly flat, but I wanted to incorporate the nuances of form and volume into the work. I had been going around to knick-knack stores and costume shops and buying little objects and painting them to try and make these assembled object collages. I liked that I could apply color to an object and the form was rendered by the light. At some point, I wanted to make a clear frame for one of these pieces, so I attempted to make a mold of this old wooden frame so I could cast it in clear resin. It went terribly. I realized mold-making would be a time consuming and expensive process that I didn't really have the patience for at that point.

So I was in one of these costume shops and I was wandering around the "adult" section and came across an ice cube tray that had these little figures fellating each other. I thought, hey this is already a mold, I could just pour plaster into this. And it sort of worked. So I went online and tried to find more ice cube trays to use as pre-made molds and ended up stumbling into chocolatier websites where they sold plastic molds of almost anything that you could want. They were inexpensive too, like three bucks a pop, so I ordered a ton of them. I think it clicked because the constraint of selecting usable objects from a limited field made me be more creative. When I was doing the assemblages, there were too many options. Working within the chocolate molds, I had a good amount of sculptural images to pick from, but was limited by what already existed in that world, which was ultimately liberating. I would have to find objects that could be plucked out of their categories, reimagined and combined with others to create these original weird tableaus. I also liked that I could make multiples of the images and objects through endless castings, and the repeated image was already something that occurred a lot in the watercolors. When they were all glued down to board and painted, they reminded me of ancients reliefs, only weirder.

After a while, I figured out how to make my own vacuum form machine so I could make quick and inexpensive molds of almost any object I could find. It got me thinking about how the mold and casting process was like 3D photography, as I wasn’t sculpting these objects, I was just capturing and reproducing them, ultimately working them into essentially 3D collages. The only problem was that I couldn’t control the scale of the object and I needed to have a physical original object to cast, both of which became frustrating. I knew I could overcome these problems with 3D scanning and printing, but the technology wasn’t quite there yet. So I began to sculpt my own original objects to get around these restrictions, playing with scale and original forms. It made making the reliefs feel more like painting. I’m currently working on a new system for making the reliefs using different computer-aided design and production methods, so I think my mold-making days are over. I’m excited because this new way is what I’ve been dreaming of since I first started creating the reliefs. There are endless possibilities for them now, with only the cost of production being a constraint.

The Monstrosity, for example, displays an intersection of many different stylistic traits you've explored over the last several years, movement of color, abstract form, symmetry, contour, all seemingly in a state of constant metamorphosis. How would you say working in 3D has informed your painting?

I had taken a break from watercolor for a few years while I explored the 3D work. But the 3D work was getting pretty intense, very large and time consuming, to the point where last summer I took a break and went back to watercolor. I wanted to create something immediate and fun, with minimal planning and low stakes again. And it was fun, and very freeing. Watercolor really is a magical medium. Since last summer, I've inched back toward the more ambitious stuff with the watercolors and started to plan a little more again, but I don’t think I would be painting in the same way if I hadn’t been focused on the 3D work for so long. Taking a break then coming back gave me a new appreciation for the medium. It also made me looser and less precious, which has gotten me experimenting with a blurry rendered look instead of the dead, flat color planes which dominated the watercolors previously.

Are you able to anticipate a range of experience for viewers of your work? How do you think your visual arrangement invites an individual to devise their own understanding about the world in which we live today?

I never know how people will react or read a piece. I don’t try anymore. I have my own thoughts that drive the piece, but I certainly like people to "finish" the thing in their own mind. It usually reveals something about them and myself that is unexpected.

Matthew Palladino’s new solo show opens on October 19 at Aishonanzuka Gallery in Hong Kong.

www.matthewpalladino.com