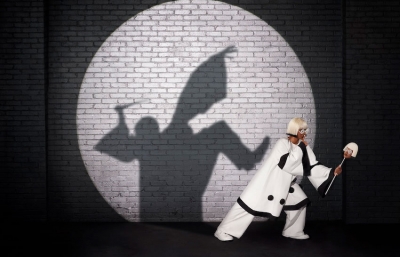

Marcus Brutus

The Colors of Connection

Interview by Harper Levine and portrait by Laura June Kirsch

Since Marcus Brutus began exhibiting his work nearly eighteen months ago, he has quickly attracted the attention of collectors and institutions alike, with two solo exhibitions, a monograph entitled The Uhmericans, and a solo presentation at EXPO Chicago 2019. In richly layered paintings, many portraying scenes of contemporary African American life and beyond, Brutus purposefully engages in the act of putting the black figure front and center on the canvas. But his influences extend far beyond the history of painting. With references ranging from music, photography, literature, sports, and socio-political history, Brutus skillfully merges a wide array of subjects into eloquent narratives that illuminate quotidian moments in black life, both real and imagined. Born and raised in Maryland, and currently based in Queens, New York, the 28-year-old artist sat down with his gallerist, Harper Levine, to discuss his studio practice and motivations.

Harper Levine: You’ve said you didn’t want to focus too much on subject matter in your paintings. What do you want to talk about?

Marcus Brutus: It’s important to talk about why I make the paintings I do, and why there is a focus on ensuring that within each painting, the black figure is central. However, I don’t want to focus too much on specific histories or specific events because I think it then takes precedence in the conversation around the work. To me, these are really just images of humanity. The only politics about them is the fact that I’ve uniquely used black figures. But they’re just scenes of everyday life, everyday situations.

It’s a good starting point, because even though there are obvious political overtones in your paintings, I’ve never thought of your work as being political, but I think some people do.

I feel like, in general, there’s only one period that people refer back to—one that they’re familiar with—and that’s the Civil Rights era. So, they think that the works are inspired by that, or the post-Civil Rights era. But I don’t paint from one particular era. I might have elements in my paintings that are very contemporary, and then I have things that predate the mid-twentieth century, so it’s a back and forth.

One thing that was interesting in our summer show, Go to Work. Get Your Money and Come Home. You Don’t Live There. was the recurrence of green. I think the story was that, looking out your window, where we’re sitting now, you saw a guy in a green vest, and that was the catalyst. But I didn’t interpret the green to symbolically mean anything other than just being a color.

I view that green as a color that marks the now. It’s a very current color. If you see a crossing guard, or if you see a cone in a construction site, they tend to be this bright green or bright orange. If you look at older photography or paintings of the past, you don’t see this bright green. No matter the subject or content within the work, the green still gave this feeling of newness. It’s something that was created recently, rather than something that’s trying to mimic another era.

I see your work as being very cinematic. There are a lot of references to all sorts of other art forms, whether literature, jazz or sports. What are you trying to distill? Is there something specific you’re trying to get at?

While there are cultural happenings that have shaped the way the world is now, I want to make sure people understand that these things are still happening, even if we aren’t aware, or we decide to tune out. I want to create connections. If you look at the Swing generation, often we’re not looking at it in terms of certain sentiments from different factions or groups in society at the time. But it was viewed by some, at the time, as a devil’s music, and it was intertwined with drug culture and oversexed society. There were all these things going on. And now, if you look at pop or hip-hop music, it has some similar connotations. What I like to do is present these images as being just one continuous thing, living all together. These are just images of life. While there are certain elements that change—fashion changes or the way we speak changes—the constants and themes remain the same.

It’s one of the things that I love about your work—there is a feeling that flows through everything that is so evocative, not reminiscent of one particular time or place, but resonant with emotion. Are you an emotional painter?

Yeah, and a lot of these works are inspired by traumatic moments in history. But what I find more interesting is that, even in the most traumatic moments, life went on—in some capacity. That’s what I’m more interested in painting, the images I want to create and put out there—the everyday, rather than these moments in time.

There was a painting called Ground Zero Heroes, which a lot of people thought was an amazing painting, although a dark and traumatic subject. What were you thinking about when you made that?

That’s a really dark moment in history, but I didn’t think of the painting in that way. I don’t really make dark paintings. That doesn’t mean they’re all lighthearted, but I don’t want to focus on dark subjects. I really just wanted to capture a moment that was very influential in my life, but then also included black figures. Because when we think of America, or the West, in general, we don’t think of black faces, or any minority faces. We don’t think of those people being a part of this collective suffering. For me, it’s part of engaging with the two-ness of being a minority in America, where you’re American but then also attached to some other specific cultural identity, as well. But they coexist within the same body, within the same space. That’s the conversation that I’ve been focusing on.

One painting, in particular, from our summer show, that I want to talk about is Day Time is the Right Time. It’s about what I would call black leisure. Would you say that’s true?

Exactly. There’s a racial undertone to being black and idle—it’s associated with being unemployed or unmotivated, or things of that nature. So, I wanted to create something that said, “No, it’s fine to be comfortable and it’s fine to be still.” There’s text in that painting that says “Idlewild,” which was a resort spot in rural Michigan where blacks would vacation during the Jim Crow era, when there weren’t many places where we were allowed. Idlewild was close to major cities like Detroit and Chicago, which had large black populations, and it was a space where people could gather together and there would be entertainment and live performers. It was also a bit classless—whether you were working class or middle class, or even of the black upper class, you would go there because we had limited options.

One of the things that drew me to your work in the first place is your use of text. “Idlewild,” for someone who doesn’t know what it was, just sort of looked like a word that was there in space. The first painting of yours that I ever saw was on Jen Guidi’s Instagram, and it was Black Magic. I didn’t even see the painting; I just saw the words. What compels you to use text in so many of your paintings?

Surprisingly enough, it’s actually being inspired by artists like Ed Ruscha—how he married text and images. The way he described it, the text would live in the foreground and everything in the back would almost be like elevator music. I kind of wanted to create paintings like that, but I still wanted to work in black figures as well. I wanted to create a more equal marriage between figure and text in the painting. The text is also kind of a reference point. Black Magic, for instance, is the name of a Double Dutch team in the ’80s—there’s a nice documentary on them. I felt like it gave the painting more life. You stare at it and try to figure out what the reference is, and if you get it, you’re curious to go look it up and check things out. It’s something that hopefully makes people inquisitive.

You and I have talked a lot about how we met—through Instagram—but I’ve never asked what you were seeking when you started posting your work. Were you hoping to find some kind of audience, or just doing it for yourself?

It was really for myself. I didn’t have any idea about what I wanted to do with painting. I always wanted to be a professional artist, but I didn’t really have any sense of how I could realize that goal. It was a way of finishing my paintings. So long as they’re still with me, I can always edit them, change them. But I felt like if I just put them out there, it was one way of saying that I’ve completed a painting, that I’m confident enough to put it out and show people. I could let go of the work. It was an early bit of training. At first, I felt like I couldn’t let go of any of the paintings, like they’re a part of me. Now, the only time I feel that kind of attachment is when I start a painting and decide that it’s going to be mine—that I’m only making it for myself. Yeah, these are all parts of me, but now I love the process of sharing them with people.

In his essay for your book, The Uhmericans, Antwaun Sargent poses the major question that he thinks your work addresses: who gets to be an American? What do you think is the answer?

What I really wanted to do with the first show we did together, The Uhmericans, was to say that these are all paintings of Americans and they’re all going to feature black people, because we don’t think of it like that. If you looked at a documentary photography book about drag queens and the book was called The Americans, would you bat an eye? You would. But if you saw one of the many things that are supposed to represent America featuring white people, you wouldn’t be surprised. You’d feel like it was a fair representation.

The Uhmericans, Acrylic on canvas, 30” x 30“, 2018

I can’t pass up the opportunity to talk about Robert Frank. When you were making work for The Uhmericans, were you thinking about The Americans?

When I was taking a history of photography course, he was one of the first documentary-style photographers who drew me in. That was kind of my starting point for really becoming interested in fine art. I liked the whole narrative aspect of it, and his capturing of life almost indiscriminately. But it was also a fair representation of America, in terms of how I interpret the work in that book. That was definitely a loose inspiration for the work, and a direct inspiration for the name.

The title also comes from my experience at museums and institutions. I would visit the NGA in DC a lot growing up. You didn’t really see art by people of color represented in a very academic or intellectual manner. So, I’m questioning how that was allowed to exist for so long. That was what my work was about: let me make an entire show about Americans, and it’s all paintings that feature people of color. I felt like that’s how people would understand why that isn’t a fair way to represent any period. It’s always something that pops up in my head. I want to know what people in Africa were doing during the Crusades! I’m always interested in what people are doing throughout the world during these major events that have shaped the world we live in—when we talk about the Greek philosophers, what were the other philosophers in other regions at that time thinking about as well? For me, it’s about addressing that imbalance in representation.

Historically, institutions clearly have grossly underrepresented artists of color, as well as women artists, but there is currently a lot of contemporary African American art on the market. For lack of a better way of framing it, do you see yourself as part of a movement?

I don’t think I’m a part of that movement. I might benefit from some of the success that these artists have had, being a young, emerging artist now. I’ll benefit because I’m not coming out of thin air. There have been examples of successful artists of color, or women artists—underrepresented artists—who have been able to thrive in the art market at a certain level. But I don’t think I’m attached to any movement or anything like that.

One thing that’s been interesting to me is that you don’t cite particular influences. Did you study art history? Do you pay attention to contemporaries of yours?

There are artists that I know or people whose work I admire, and I like to follow the trajectory of their careers, but it’s not connected to my journey at all. It’s more so just as a fan.

I didn’t study much art history in a very academic space, but I think of myself as an artist who came up with his own curriculum. I have to rely on reading books, I have to watch documentaries, I have to visit museums, and now that I’ve had a little success, I’ve been able to meet other artists and discuss painting with them, learn from them. I still have to go through the coursework, but I’ve created my own curriculum on how I want to attack that.

In the work that you made for UNTITLED in Miami, I felt like the paintings were looser. There was almost a psychedelic vibe—more drips, more experimentation with paint. Do you feel freed up now that you’ve had some success?

It’s more about being comfortable now. When people aren’t familiar with you, you kind of feel the need to show all of your best characteristics at one time, and it can be an overload. Now, just having this confidence, it can lead to more experimentation. I also got to this point where I’m reading about artists of color that work in more abstract realms—Frank Bowling or Sam Gilliam, for instance. Figures are a very easy way to discuss representation, but when it comes to abstract work, that’s an entirely different realm as far as discussing representation. You’re even more so introducing something like black intellectualism or black feeling. You’re entering into the realm of humanity in that way. I want to find a way to marry the two.

Portrait by Laura June Kirsch