Your paintings often incorporate poetic text. How did words become part of your composition?

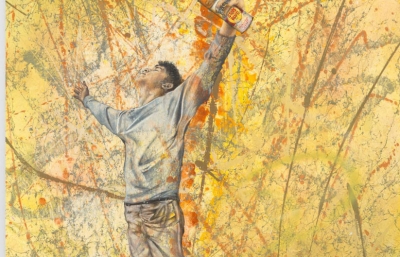

Visually, going back to the subway era, an entire 52’ long car painted is so out of the box, out of the norm, that when it comes, it takes you hostage in a way. I think people were very much intimidated by that. There were a lot of things in New York that intimidated, frustrated, and frightened people, for good reason, but when you saw this coming around and gobbling you up to take you somewhere uptown, to your job, or wherever, I wanted to make it more of an experience. I wanted to have a reading session with the public. I thought words were always captivating, and they still are.

Words are power, and when you have words incorporated into a visual, it starts to lower the level of fear in people because there’s an attempt by the person, the practitioner, to make some kind of dialogue happen. I think there was power in that, especially in something on a subway car where you would never expect to see anything written, unless they were trying to sell you on how to correct hair loss or how to pay your unpaid taxes and never get taxed again. Like all the stuff that you’re exposed to on the interior of your car. There’s nothing on the outside that is forgiving, and other than this regimented blue line that goes across, that’s supposed to give you an idea of some civil municipality. It’s frickin’ New York, 1974! Dude, it’s falling apart! You’re trying to tell me that this exterior is now going to make me feel good about everything outside of it?

I’m going to write because I want to grasp the imagination of every scrap hanger, but I also want to start lending a hand to other talented painters who are painting in this theater of operation and let them know that this is beyond the name. This is beyond your narcissistic approach to yourself, not that there’s anything wrong with trying to preserve yourself by painting your name over and over again. I think there’s something about self-agency and strength in that, but it’s also something that you can get drunk on and not recover from. I felt I needed to add more verbiage and actual language to this so that people cannot be offended at first and not look away but be condemned to look at the writing and then say, “Oh, this young soul, whoever he or she is thinking, is verbalizing those thoughts to me when they don’t have to.” I felt that that was my calling at the time.

After 1978 [the Howard the Duck handball court mural], that was the strongest statement I remember repeating to myself. If art is a crime, let God forgive us all. Let God forgive me. The reason for that was because we are already saying that art is a crime, and we’re saying graffiti because it’s not in the verbal acceptance dictionary. It’s something strange and thereby should be shunned away because we don’t want to understand it, and we don’t want to understand the circumstances that made it happen in the first place! If you don’t want to understand the underpinnings of something, you obviously aren’t going to understand when it evolves and matures itself into something that is really in front of your face. I think all art is rebellious. When you create art in that context, you’re creating a whole different experience in terms of how you approach your art and how art approaches you.