Kate Pincus-Whitney

Generosity of Spirit

Interview by Shaquille Heath // Portrait by Max Knight

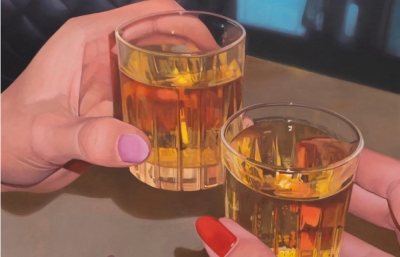

It has been a long two years of heavy stillness. I honestly believe that at the deepest point in the pandemic I could have easily taken a finger and dragged it across my thigh, unsurprised to find it caked with a weighted blanket of dust. But now here we are, venturing out at “normal” rates to see loved ones. Sit at tables to share a bottle of wine, spill some secrets, dip into the same bowl of salsa, and most importantly, revel in some good art.

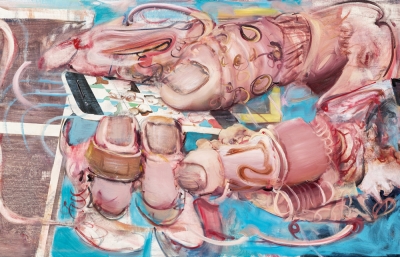

Kate Pincus-Whitney is one of those artists who seizes the significance of such moments, exalting the table-space with the consideration and devotion that it deserves. Using her own words, her decadent paintings engage with the “the theater of the dinner table.” Her hands suffuse everyday objects, from Triple Sec bottles to cans of cream of mushroom soup, with divinity and purpose. How we identify, both to ourselves and to others, become mirrors in the form of edibles and the like. Old Bay seasoning is coupled with memory. A box of Zatarans is now a place for communion. These paintings become altars of connection, confessions of memories, and shrines to our most mundane but cherished possessions.

Our conversation went deep, quite like the complexity of her paintings, and of course, it would materialize in this way. Although we spoke from different cities in California, we could have easily been together at a table, drinking Peronis and diving into a bowl of olives. As much as we are ready to “go, go, go”, there is always that anticipated respite at the end, and. Pincus-Whitney reminds me that it's usually around the magic of a table.

Shaquille Heath: I have friends who always ask me about what artists I’m interviewing next for Juxtapoz, and I feel like I've had a really hard time describing your work. Because in essence, in the purest form of essence, you make these beautiful still-lifes. But the word “still” really diminishes the substance of your art. I’ve heard you describe it as narrative portraiture–which I love, but how else would you describe your work?

Kate Pincus-Whitney: I would describe… like the essence, essence, essence of it is “the theater of the dinner table.” That is my entry point into that space. I'm looking at identity, at the object’s identity of things. I'm synthesizing and pairing, combining to make these larger allegorical scenes. But at its essence, what I am mining is this duality of the sacred and profane. Materiality and also self and identity. And so with that… yes, of course, when you come upon them or you come face to face with one of the paintings, it takes a moment to unfold.

One of my pet peeves is when people are, like, “Oh my god, picnic still-life!” Yes, obviously. But all of them have these much larger, loaded meanings that are synthesizing mythology and contemporary life. For example, to channel something deeper, larger, for example, one of the paintings I'm working on right now, is for an up and coming show. It's an ode to the apple pickers, and so within that, it talks about divine femininity. It's talking about the Garden of Eden and Eve. Referencing Mary Cassat. It's a push/pull thinking about femininity, knowledge, what has been forbidden, sexuality. It's talking about the history and the symbology of this thing. And also, contemporary life and womanhood, right? And so I really think of the paintings as a place where I dive into the unconscious, as a form of Jungian sandtray. Do you know what that is?

No, no, I was gonna stop you. Please tell me more.

So, my mom Laurie Pincus, is an artist, but also a play therapist. The Jungian sandtray, basically, is this tray of sand where you engage in a session, surrounded by hundreds of thousands of small objects that all have these loaded meanings that you are totally unconscious of. But they're archetypes. They're actors. They're all these different things. And so through the conscious or unconscious process of picking these historically, politically, archetypically, loaded objects, and arranging them, you discover it’s the relationship between the things that creates the larger narrative.

So I feel that in essence… it's funny because it's like, oh, yes, obviously, utilizing objects in still life. But sometimes they're shrines where I'm literally, communing with both ancestors, the alchemists… everybody. It's a sort of translation, like, who am I inviting to the table to engage in dialogue with for a specific piece?

In a simpler form–and I even hate saying “to simplify it”, because … Why? Why do we need to simplify things? That is what is so fulfilling about your work, is that it's not simple. So I can imagine how frustrating that sense can be. Because it is deceiving. It's so fun! And colorful! And I love how you call it boisterous. There's so much going on, you could spend so much time focusing on just one corner.

Right!? Well, it's also interesting, because, in that way, each piece gets to act as a sort of a mirror. The artwork that really touches me is something that does that, where it reveals something about yourself, and that is the absolute magic of the universality, and personal aspects of food. Where, as I've talked about sometimes, there’s this perfect example of when you see a Lillet bottle in my painting, it's me divining and having a conversation with my grandma, because that is something that is so deeply inside my sense memory of this person, who's no longer here. And that's also what I love. These paintings get to kind of live in this weird wiggle space, where you can't really pin them down. Where, “Oh! x plus y doesn’t just equal z,” but instead honors the linguistics of the actual thing, and it gets to commune or talk to you. Sometimes the painting, well, I don't plan things, really, when I start painting, I don't draw it out. There’s no amassing of preparatory sketches because I don't find that it's really important to be in this continual open dialogue. Instead, all of a sudden, weird things show up, and you're like, “Oh, this is the direction that the painting is taking us.” There will be a portal or threshold of an idea but once I enter into the conversation I allow the material and the magic to take hold. It's interesting because for somebody to come upon it, on the surface, it’s a “pretty still life.” Then you start allowing the associations and the actors to come through. A sort of Trojan Horse. And that's what I love about it.

Absolutely. There is so much at play. But, okay, I need to go back to your mother. She was an artist, but tell me about her other profession. What is a play therapist?

What is this? What is this? Haha. Okay, so she was a female artist working in the 1970s and ’80s in LA. Then she had a child. And then, of course, the art world being incredibly sexist—shocker—was like, “Oh, you don't exist anymore. Mother? Nooo.” So at that point she ended up going to Pacifica Graduate Institute, studying Jungian therapy, dream work, and play therapy. She, of course, continued as an artist but also while doing this. So growing up, literally, I would be placed as a child, sitting in the sandbox, playing with all these objects, which I knew had all these intense meanings. And it's still, 100%, absolutely the way that I “play” in the studio.

That’s what I was thinking, and it must have had some sort of influence on you. But also with all that time, I'm sure you've learned a thing or two from your mom. And I'm sure it's really fun interacting with people when they engage with your work and see what they gravitate towards. Just having this analysis in the back of your head like, “Hmm, okay, so that's what's going on with you….”

If I were Freudian I would turn around and be like, “This is what this means. Sex. Repression.” But I'm much more Jungian. Haha! You know, so also, when in undergrad, I consciously was like, I am not going to art school. I'm not interested in this. I want to learn about what it means to be a human in the world. So I studied a lot of neuropsychology, cultural anthropology, and ethnographic studies. At the core I was basically just like, existentially, what does it mean to be a human? How do we make meaning? All that stuff. So it is always so interesting… I love people watching. Observing people interact with things and seeing what they get called to, and what resonates with them.

So, I am really into spooky, scary things. And San Francisco has this columbarium–which is a place that holds funerary urns and cremations of the deceased. I visited a couple weeks ago. I guess I never really realized what those places were like. They had these glass shelves where you could see inside the box. It sounds intense, but it was really lovely because you get to see people's personal belongings that were left for them. For example, there was this really stylish grandma who had included her Chanel lipstick. And you could see the image of her in this big fur coat and you got such a sense of who this person was. To even silly things, like the dad who was a big Giants fan. He had his Giants baseball cap in there. It got me thinking about materiality. And I couldn't help but think of that in relation to your work, and how often we think about people, not in the sense of what they were, but in the material things that defined who they were. And the relationships that we have to that.

Totally, so there was William James, whom I studied in the Psychology of the Religious Experience class. One of those things that he used to talk about was how our understanding of self is not just our kinesthetic, our psychological or emotional self, but is actually the objects that we surround ourselves with. They are imbued with who we are. And that, to me, actually captures the essence of a person or a relationship so much more than like, the curve in somebody's nose, right? And it's also having those moments where you get to touch those objects… that to me is also a perfect example of the living breathing duality of the sacred and profane, right? It's like, Giants hat, very profane, ends up becoming this object, icon, relic because it is imbued with this personhood. I love that.

I love how you were like, “I love spooky things!” And then you’re like, “Actually, this is just like…”

No, I mean, that was the thing! I went there too, you know, it was spooky in its own way, right? But I actually just felt so much reverence there. There was just so much depth that I feel you don't really get in a graveyard. Not that I'm, like, traversing graveyards…

I mean, I do love a good traverse of a graveyard!

I do love a good graveyard. When I was in LA back in January I finally went to Hollywood Cemetery for the first time, and that was really interesting. But you just don't get that same experience like, when you can see someone's objects or a photograph or just really feel them. But not to get too distracted with graveyards, because I do want to go back to you. I know that you said that when you come to a painting, you come to the canvas with nothing in particular. Like, no objects ready in your mind, so I'm wondering, what do you come to the canvas with? Is it a feeling? Is it a vibe? Are you thinking of a person and then creating with them from your mind?

Absolutely. Okay, so what I do process wise, literally, is I will write directly onto the canvas in paint. I will divine. I will call and call to things and have this very abstract engagement with the material that immediately imbues meaning into the canvas itself, and I don't have to remember what that is. It might be anywhere from a poem of Maya Angelou, to calling to somebody specifically. After that happens, I do a lot of physical work on it. Abstracting the words. And then I age them, like a cheese. I like to put those away until I don't know what is in there. And then when I come to an actual starting of a piece, to me, it's like a portal. That's like the best way that I would describe it. But I definitely do have something in my mind always. Sometimes it's directly channeling a person, where I’m really interested in both researching the life and understanding a person through the objects they created, as well as what was so meaningful to them, a sort of portrait conjuring. How do I create a shrine calling to this person? So we'll do research and I'll start gathering objects.

Or let's say, I'm working on something… like right now I'm starting to really work towards this solo show, The Gods Are In the Kitchen, (my next solo show with my home gallery Fredericks and Freiser opening this September in New York.) The way that I am entering into the portal is much more through the alchemical and honor of the elements and material, so I'm thinking through it in that way. But I can't go to something without some sort of, not even play, but like, some poem, or play, or person. Trying to understand. A series that is an ongoing series for me called “Paradise a la Carte”– carte in French means both map and menu, and so it was like each piece specifically was diving into a place through its objects. So something like my physical relationship with having grown up in Santa Barbara and going over the hill to Santa Ynez Valley and like, how do you capture the essence of this place? That's when I start gleaning and grabbing all of these objects, some of them mythological, some of them not. It depends on who I'm communing with. And then I'll draw them with chalk on the canvas itself. And then it's a go. And things get wiped out. And that's when it's like, the language. And the reality of the canvas starts opening up and speaking. And then it's that dialogue thing.

"I want a Jungian analyst, an art historian, a high priestess, and like, grandma, to come sit down and all tell me what this painting means."

Fifty years from now, or actually, 100 years from now, it's gonna be really fun for some conservationist to x-ray your work and be able to see the different layers of how your mind was flowing as you were creating work!

Totally. I'm like, I want a Jungian analyst, an art historian, a high priestess, and like, grandma, to come sit down and all tell me what this painting means. Because it will then, like through all of them, actually be able to start a conversation about the thing that exists in that space.

I want to be at a table with all of those people, generally. So you said you didn't want to go to art school but knew that you wanted to be an artist, probably when you were pretty young? What is it that brought you to becoming an artist?

I was lucky that I grew up in a very creative family. My father's father, John Whitney, was one of the first experimental filmmakers who was obsessed with making visual music. And then on my mom's side, they were all theater people, early television people. Her father created the Real McCoys. So “sacred storytelling”. Like, this is who I have on my shoulders. But growing up, I was, and am, incredibly dyslexic. So I really did not understand the world in the typical way. And so for me, I understood everything through and synthesized everything through the visual. It's funny because within that process, cooking came into play. I was raised by a single mom and grandma, and I used to spend the majority of my time skipping school to cook with her. We would go to like six different markets in a day. I was learning about the world through a means that made sense to me, and I was honoring that experience instead of being ostracized and emotionally abused by teachers repeating the montra, “you're stupid.” Because I was different. It took a lot to be like, no, I actually just engage with the world in a different way. So I was always drawing and painting and all of that since I was able to get my hands in paint. I would have people reading out loud to me constantly, and I was really negotiating the drama of life through the visual.

Then, when I was 16 I lost my grandmother. She and I were living on the same floor, and our bedroom doors, which never were closed, were opposite each other and always open. I remember that day of coming back from the hospital, and going and touching all of her objects, because I felt like there was the potential to touch that one last ineffable thing that was hers. To feel her. Because there've been a lot of deaths in my life, I knew that, in that moment, the magic of her being still existed in these objects. I think that was the moment also that I really turned to creating and painting in a really serious way. Because all of a sudden, these larger questions of, how do you capture the essence of a person and how do you capture the essence of a relationship came through in that mode of thinking. Then I thought, okay, well, that’s cultural anthropology, like learning romantic poetry and its legacies. So I ended up going from that moment to Sarah Lawrence in New York, because I was interested in understanding a larger concept of what it means to be alive. And I knew that I would be filtering it through my own didactic visual vocabulary.

I'm so sorry. I lost my mother when I was 17 and I feel like it's a really hard age, as you're finding yourself as a woman—to lose that guiding person. It's awful.

It's awful. It's also one of those things, too, where all the sudden, there's that moment of innocence that's lost that you will never get back again. And in a weird way, I feel like it enables you where you can go into the space of just being removed. Or you can also become a seer, in a way, where you are aware of the world. It's like the same thing as a first love. Like really having your first love and really losing your first love. All of the sudden, music sounds different. Food tastes different. You are interacting with the world on such a different level. I think, for me, whenever I get lost in the path of “What am I doing? What does this mean?” I think back actually to those moments that kind of blow open your perception and understanding on how big and small the world is. That you're like, “Oh, it's totally divine. And it's totally awful.” But you can't taste the sweet without the bitter.

Absolutely. The duality of life. So speaking of taste, one of the things that I missed the most throughout the pandemic is being able to sit down with loved ones around a table, a table so full and rich and delicious as the ones you paint. I imagine all of these people coming together from different places across town to this one destination which is the table. I'm also a huge Carrie Mae Weems fan and I’m reminded of her Kitchen Table series, and the role of “the table”?

That series is one of the most poignant, profound, deep, quiet… It's just incredible. To me, the table symbolizes this space of intimacy where we all take off the masks that we're wearing outside and we actually deeply connect and share with one another. And in that space, it becomes a theater. That space becomes a commons. Weems’ pictures… witnessing them, you feel almost like a voyeur. But at the same time, there's something so intimate that you do actually feel like you are welcomed into the space. For me, that is something that I try to do in my paintings. I want that generosity of spirit, to be able to invite anybody into this space. Come be intimate! Come be loved! Come cry, come grieve, come fight! Let's remember what it means to be and to relate.

Growing up, when somebody died, we sat at the table. When somebody was born, we sat at the table. My mom's heart was broken, we sat at the table. My heart was broken, we sat at a table. All of the sudden my grandmother was no longer there to sit at the table with us. But we still held her space. The profundity in that theater–that, to me, is what that space symbolizes. And not just symbolizes because it actually gets to enact that thing! It is an embodiment of that, simultaneously, so unbelievably deep, universal, and personal.