Justin Liam O'Brien

A Freed Style

Interview by Evan Pricco // Portrait by Laura June Kirsch

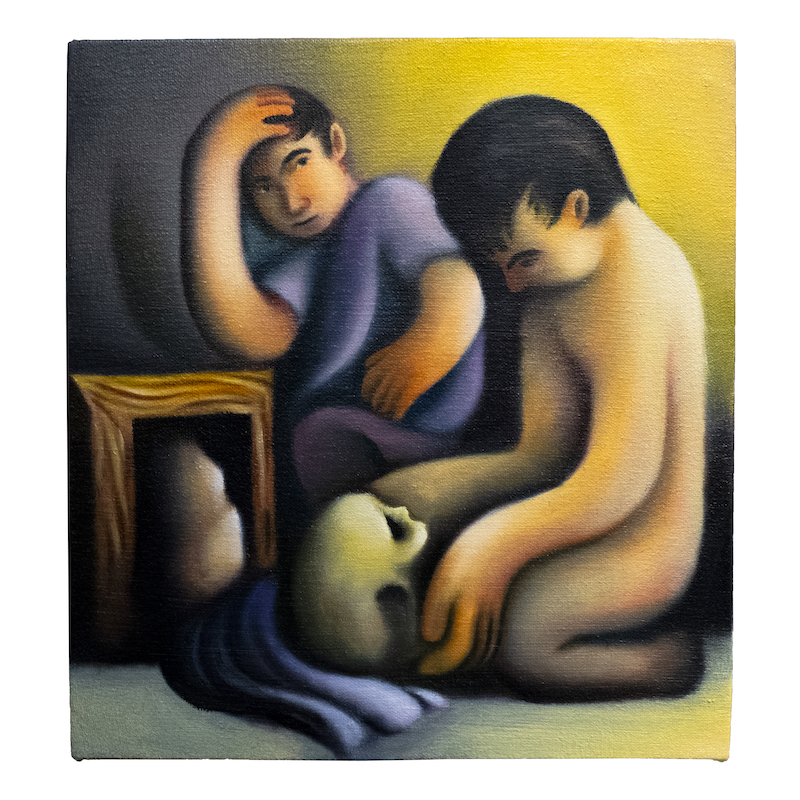

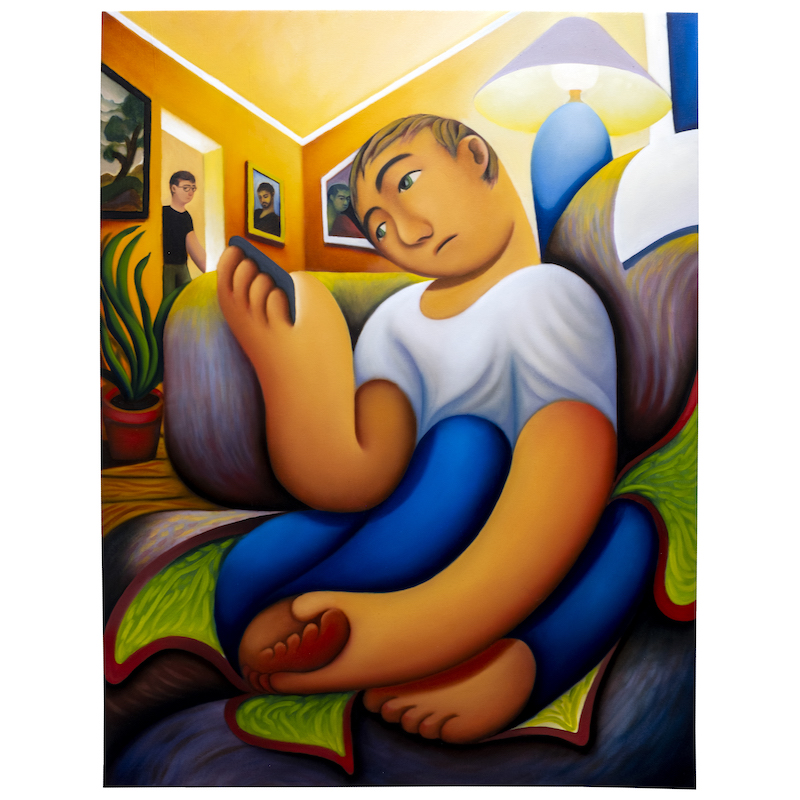

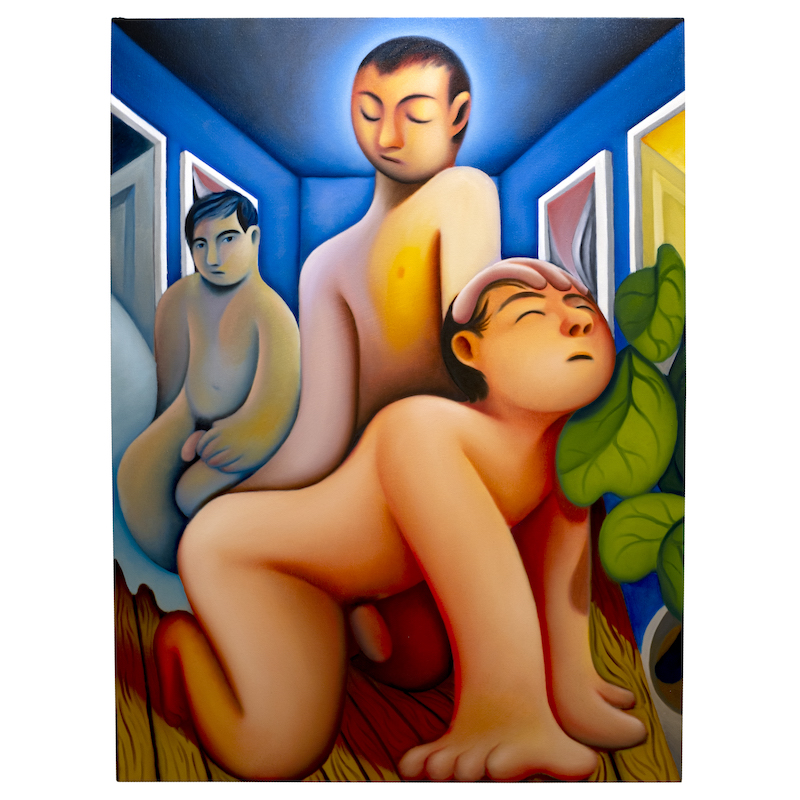

Through the chaos and divide that America has gone through in 2020, from the minor ups and tragic and enduring lows, moments of clarity emerge. For painter Justin Liam O’Brien, 2020 is a bit of breakthrough through a break-up: leaving his day job behind in 3D modeling to focus solely on his craft in his studio, resulting in a stunning new direction with his show this summer, Dammed By the Rainbow, at GNYP Gallery in Berlin, and his upcoming fall exhibition with Richard Heller Gallery in Los Angeles. The intimacy in these works, speaking on topics such as Queer identity, isolation, sadness and humor, have begun to evolve as O’Brien becomes more seasoned in his practice. From his early aspirations in video game design, to finding inspiration in the career of David Wojnarowicz, with the world in flux, O’Brien is finding meaning in this new chapter in American painting.

Evan Pricco: I didn't realize until I was doing a bit of research that you studied digital art at Pratt, but then when I looked back at your works from 2016-17, it made a lot of sense.

Justin Liam O’Brien: Between 2013-16, yes, I was at Pratt doing 3D animation. The way that I got into this whole thing was actually through video games and 3D art. Which is interesting to some people when I tell them, because when they look at my paintings, they see these really simplified, blobby, 3D model-ly characters. That was somewhat intentional in the beginning, and it took off from there.

Justin Liam O’Brien: Between 2013-16, yes, I was at Pratt doing 3D animation. The way that I got into this whole thing was actually through video games and 3D art. Which is interesting to some people when I tell them, because when they look at my paintings, they see these really simplified, blobby, 3D model-ly characters. That was somewhat intentional in the beginning, and it took off from there.

It's not really present in my mind anymore, but it definitely made its way into the visual language of the pieces. It's funny how these things have a carry over, whether you want them to or not. I actually just quit my job, where I worked for a real estate company, making 3D models of interiors, and warehouses, and stuff like that. And in May, not because of covid, it was actually completely separate, but they laid our entire team off. Since they didn't really offer me a very good severance package, I said, "You know what? It's fish or cut bait right now. Maybe I should just dive into the painting thing, and really commit to it." So, it's been two months of just full-time in my studio painting, and I haven't been happier in a very long time.

It feels like you’ve disassembled your 3D elements and got a bit looser in the last couple of years, like you're starting to find your original voice.

And to see it happen in myself, too, is so mind boggling. It’s almost like, "Oh my god. I'm making paintings that were in my mind, but I just didn't know it."

Would you say you grew up in a house that lent itself to working in the arts, or even video games?

I was certainly encouraged to try it and express myself. I grew up more around music. My mom, if anything, had more of an interest in music, but she had painterly friends. It wasn't really the fine arts. I was introduced to all of that stuff in college, and of course, to Juxtapoz. When I first encountered the magazine, I was in my teens, and I was really interested in modding video games, drawing concept art and graphic novel-style art. That's how I learned how to draw figures and how to do perspective and all that stuff. It's so put upon you in that field, knowing how to come up with a scene, or a character, at the drop of a hat, in a snap of a finger.

I always had that skill, as I was very seriously involved in making video games up until I was 22, 23. Then I went to school for animation and using those skills, but it really wasn't coming through. In about 2017, I started painting. And I started using those methods to try and make pictures about the stuff that I cared about. The problem I was having was that I was sublimating a lot of my feelings, my emotions, but it just started to click, just like that, the visual language thing, and all of the stuff that I was going through, coming out as a Queer person. I started to try and put those two things together, and it really started to work. There's also this whole thing with being here in the city, and making connections, and meeting the right people. There's definitely a social element to this whole art world thing. I was also being influenced by people like Lou Fratino and Danielle Orchard, to name a couple.

Let's work this out. When I think of animators or video game concept art, increasingly, as video games have evolved, the idea of creating emotions and personality, and really deep storylines have emerged. Video games are attempting to do more and more with emotional settings. Was there something there that you connected to, like escape as an artist, or immersion in alternate reality? That must help you as a painter.

I think the reason I was so drawn to video games in the first place was because they offered up a visually stimulating environment, as well as an escape from a relatively hostile environment, and one that I didn't need to fit into—in the same way that you do in high school, or early college, when you're still trying to figure yourself out, who you are. Suffolk County on Long Island, where I grew up, is a very backward-minded place, very homophobic. And it didn't offer me very much in the way of any avenues to come out, or be myself, or express myself.

So video games, online communities and people on the internet, I would say, in a lot of ways, are like a Queer counterculture. For years and years I did this. And so, as much fun as I was having, and as profoundly as I was escaping my environment by playing video games, I was also like, "I think I see a future here, too.” I think I can keep doing this, and maybe do it more professionally, because I'm good at painting, I'm good at drawing. I'm good at 3D modeling.

Painting offered me a very delineated, very clear community of people I wanted to be involved with, too, in the exact way I wanted to express myself, which is through images, and endless space to explore. Whereas, with a video game, you're making characters, and drawings, and environments, for the purpose of the game. And by somebody else's rules, for somebody else. It's not a free expression the way that painting is.

There's a lot of storytelling in each of your paintings, too. So, you're playing around with this idea of escapism and narrative in something that is more of an isolated creative output. It’s just you.

Animation is telling stories over time. I'm not good at that. I'm really not good at creating movement to tell a story. I'm good at getting a single image to tell a story. I know how to do that. I understand the dynamics of where to put a figure, to imply a mood or feeling about something that is going on. I can't do that with a 3D animation or a movie. I don't know how to do it.

But you can get that in a single image. Do you feel, in your solo exhibitions, that you're getting better at telling a themed story through painting and being a cohesive storyteller in one show?

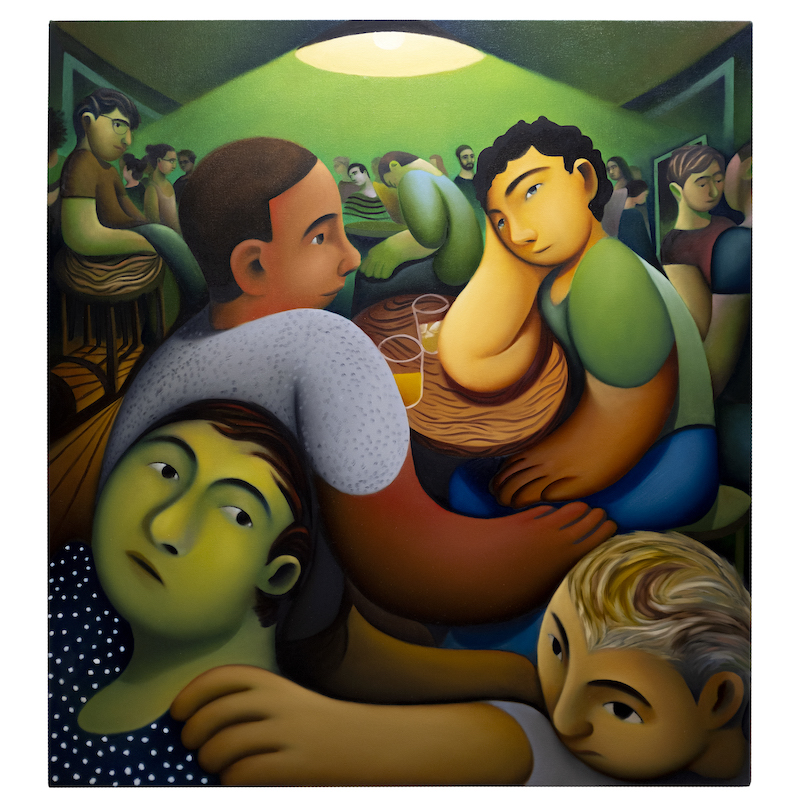

For sure. I was just working on this painting for my upcoming solo show this fall with Richard Heller Gallery. It’s a painting of a group of people sitting at a table. I didn't know what I wanted from it, didn't know what the story was going to be, or what it was supposed to be about. But, as I've been painting it this week, it’s been changing. It was this happy-go-lucky, feel-good image of people at dinner before. And as I'm working on it, I'm just starting to feel this theme. I'm thinking about coronavirus, and the world's going up in flames. The faces are just turning inward, and they're getting a little more serious. I changed the figure, the figure spread his arms out, across two people. In changing it to be like he's falling back in his chair, with his arms spread out, he's trying to grab for help.

So I'm getting more comfortable, and more loose, with working on changing that story to be more meaningful to me as I'm working on the paintings. I'm getting way better at that. Before, for the first couple of solo shows, I had to draw everything out, and have everything just so, in a sketch, before I even started painting. And then nothing changed between the drawing and the painting. Because I just didn't know how to paint well, I didn't know what I was doing. Everything in the drawing needs to be on that thing, and if I try anything else, I'm probably fucked.

Now, in a way, as your confidence grows, you're letting the images tell you where they should go, which I think is probably something about a feeling of comfort.

Absolutely, absolutely, absolutely, yeah! That's exactly what it is. Even today, things happen a lot faster, because I'm just so much more comfortable with putting colors down, and being a little messy. Just letting myself realize that it will work out in the end, narrowing in on that image, tightening it up, just everywhere. You're just tightening, tightening, tightening. Or, it’s okay for it to be loose.

Originally, I thought it had to be a tight, finished looking at the painting right from the first brush stroke. Everything had to be perfect. But that's not how paintings are made. It's really not. It's a pile of oil sludge that you push around until you make it into a sensible looking thing.

"... it's about feeling alone in a crowd of people, really. That's a good way to say it. It's this internalized feeling of loneliness."

I love how you jump around between groups, two people, and single characters in your paintings. There are these dynamics that are playing out, like the play of our lives, how we feel around large groups of people we don’t know, then our intimate groups, and then how we feel about ourselves behind closed doors. These emotions feel even more powerful this year. You capture the idea of being alone in a special way, if this makes sense.

Yeah, it's about feeling alone in a crowd of people, really. That's a good way to say it. It's this internalized feeling of loneliness. I was writing about this the other day. And I was thinking about loneliness, not as an acute condition, like a momentary thing, but as a recursive pathological thing. Loneliness is like a disease, or just this thing that you carry, rather than it being just like, "I feel lonely right now." It's more profound than that. It's more lived. "I'm living with loneliness, as a feeling." But, it's also about those tender moments of rejoining with people, or connecting, or clicking with people. It can be about that click…

You are speaking of feelings that are hard to articulate.

Right, which is why I gravitate to painting, to try and work them out. And I always feel like I fall short when I try to describe it with words. The feeling is one of speechlessness, or wordless-ness. Of this intensive feeling in your chest of, "I don't know why I'm having this extreme feeling right now." Loneliness, lust, anger, or feeling rejected, those feelings can become so complicated and so overpowering, that you just can't speak about them.

This may be off topic, but we were speaking about finding your community, and NYC has this historical aura of the art community, of nightlife, and seeing people, and people coming to your shows. It's magical, really. Did you ever worry this year, that maybe New York wasn't going to be able to hold it together, and you would have to leave?

Yeah, literally. Yes, yes. In this moment, it's very strange to live in the City when it is stripped of its character. Another thing that I think about a lot when I work is this history, this lineage, the heritage of being a Queer artist in New York City. And I think about Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz, two huge, big deal people for me, who were here in the 1980s. I'm reading David Wojnarowicz’s biography right now, Fire in the Belly, it's a really great book.

I was introduced to David's work in 2017 by a friend. It blew my mind, it changed my life. And consequently, it's influenced my reasons why I make the paintings I do today. It's probably the reason why we're talking. David Wojnarowicz is, hands down, the most influential artist for me. But, it's funny because, when you listen to his story, and Peter Hujar’s, and of all these people like Kiki Smith, all these New York City artists, Beat Generation, there’s all of the color, all of the nightlife. It has the CBGB, it has Patti Smith, it has all that shit, which is why everyone wants to come here. It's why everyone wants to see this city, it's SoHo in the ’80s, this really sexy New York City nightlife. Right now? Everybody's in the park trying to keep their head on straight, pulling their hair out of their heads. And you're like, "I'm supposed to be living like Robert Mapplethorpe, like now? What do you mean?!" It's like, "How does this compare?"

I love that you mention David. He was all over the spectrum of the creative world. He wasn’t just one kind of artist. He was everything. Is that an inspiration? It also could be daunting to be everything.

I think about David as somebody who did not need to be a painter. He did not need to be a poet. He did not need to be a writer. He was just all of them. And I'm learning through this biography, that he really was very, very troubled. He didn't consider himself a painter, he didn't consider himself a writer. He was just like, "I'm a person that does stuff." Which is a funny, old school way of thinking about art. My introduction to Davis was Close to the Knives, his memoir, which ripped my heart out of my chest. I was also, at that time, 24, looking for a way, still kind of inching out of the closet. And then I was dating guys, and one of them just gave me this book, the memoir. I still have the copy that he gave me, and I read it, and I read it again. And I read it again. I was like, "I have a culture. I belong to a culture. There's a history of Queer people. There's a culture here for me." And I just latched onto it, and I just haven't let go. And I journal, prodigiously. I'm not a good writer, but I write all the time. I sketch, I draw, I do pastel sketches. I think about David all the time, because he just didn't ever limit himself to that one medium. And I'm hoping that once I'm not as slammed for paintings, I will be able to explore more things.

The works you made in your Germany show were really beautiful and strong. Was that a body of work that you knew you were feeling good about when it left your studio? Like a direction you wanted to pursue? There were elements that felt a little new to me.

Definitely. I mean, honestly, the primary reason that those elements were there is because I quit my job in early May. So, the last, I guess, 30 days, I really was ripping through those canvases and dedicating full-time hours to making those paintings. Because all the work that I've done, including the solo show that I have in Monya Rowe—I did that in the margins. I did that on the weekends, I did that at night. I wasn't really singing that song very loudly, but I was making it when I was forcing free time to make it. I didn't realize how much better the work could be if I had all of the hours of the day dedicated to it. So the paintings in that show in Berlin are so much stronger, because I just had the time to make them so.

It’s really amazing to be able to have the time to fully realize some of these ideas that I have in my head about how light should play on a surface, or maybe experimenting with patterns and all these spatial things that I've been trying out. They work, they actually work. If you just have the time to try them, more or less, they work. It's really cool to see, yeah, very exciting.

I initially thought there was a chance that you were European from the first time I saw your works. Now it seems interesting, because some of the influences you've mentioned are not European.

I'm not offended at all, I think it's so cool that you're saying this. Yeah, Germany was super into it. I don't know exactly why. I can't tell you very much about Central European art, especially contemporary European. But I'm looking at Wojnarowicz, Diego Rivera, and then I'm also thinking about Grant Wood, for example. The references are eclectic, I'm not just thinking about one type of thing.

This is also what David was. David was attempting to change it up, change it up, change it up, stop doing the same shit. I mean, very clearly, this is why I'm resistant to the idea of being that artist that just narrows in on one thing and does that, like a one trick pony kind of thing. I don't want to do that. I hope that in five or ten years, I can completely reinvent the work that I make.

Besides the solo show at Richard Heller, what are you looking forward to right now?

It truly is just like staring off into the blank, middle distance and waiting for the engine to start. That’s what I’m looking forward to.

Justin Liam O’Brien’s solo exhibition at Richard Heller Gallery will open in November, 2020.