Julian Schnabel

Painter, Director, and Ensemblist

Interview with Max Hollein by Gwynned Vitello // Portrait by Evan Pricco

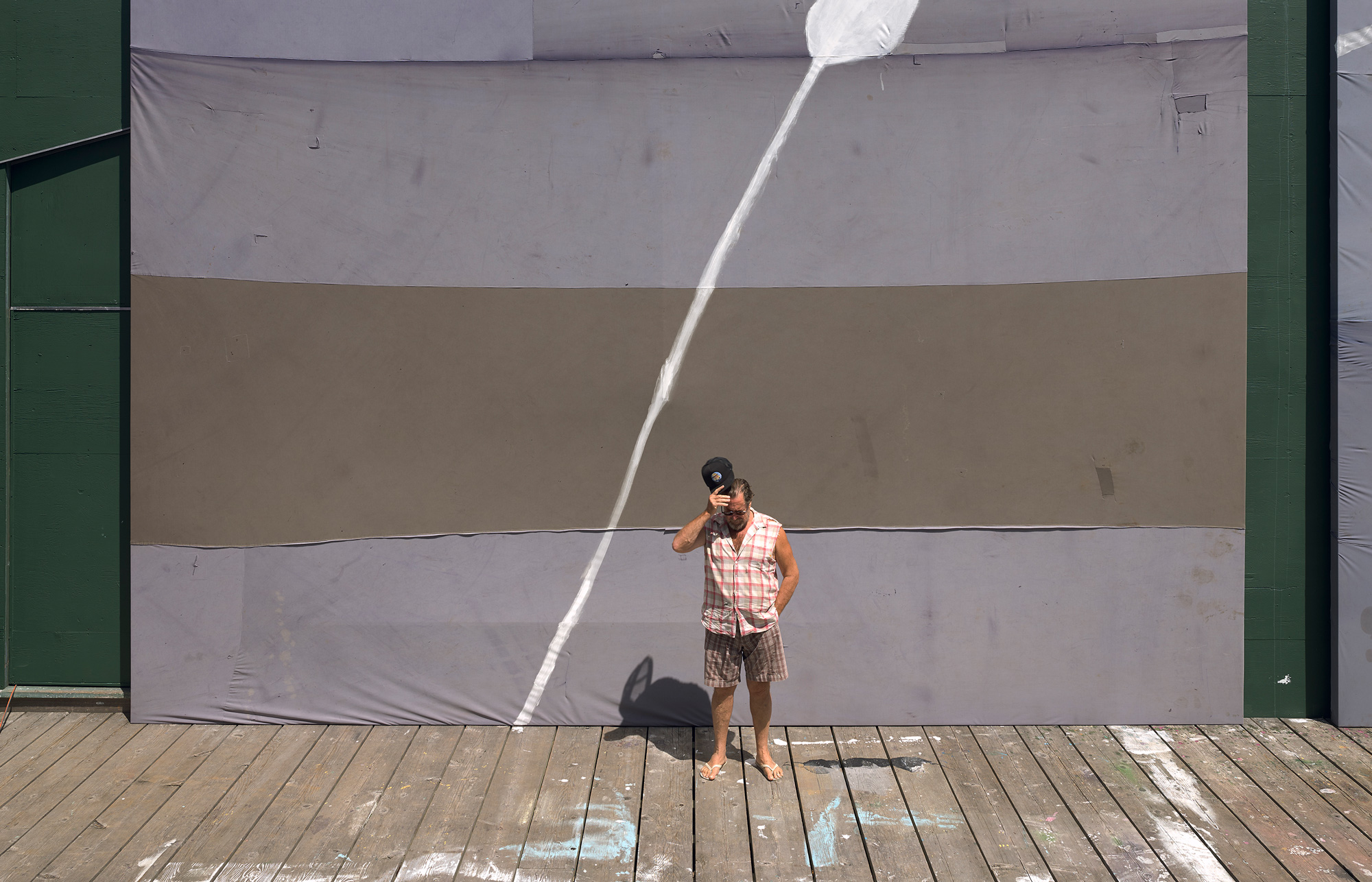

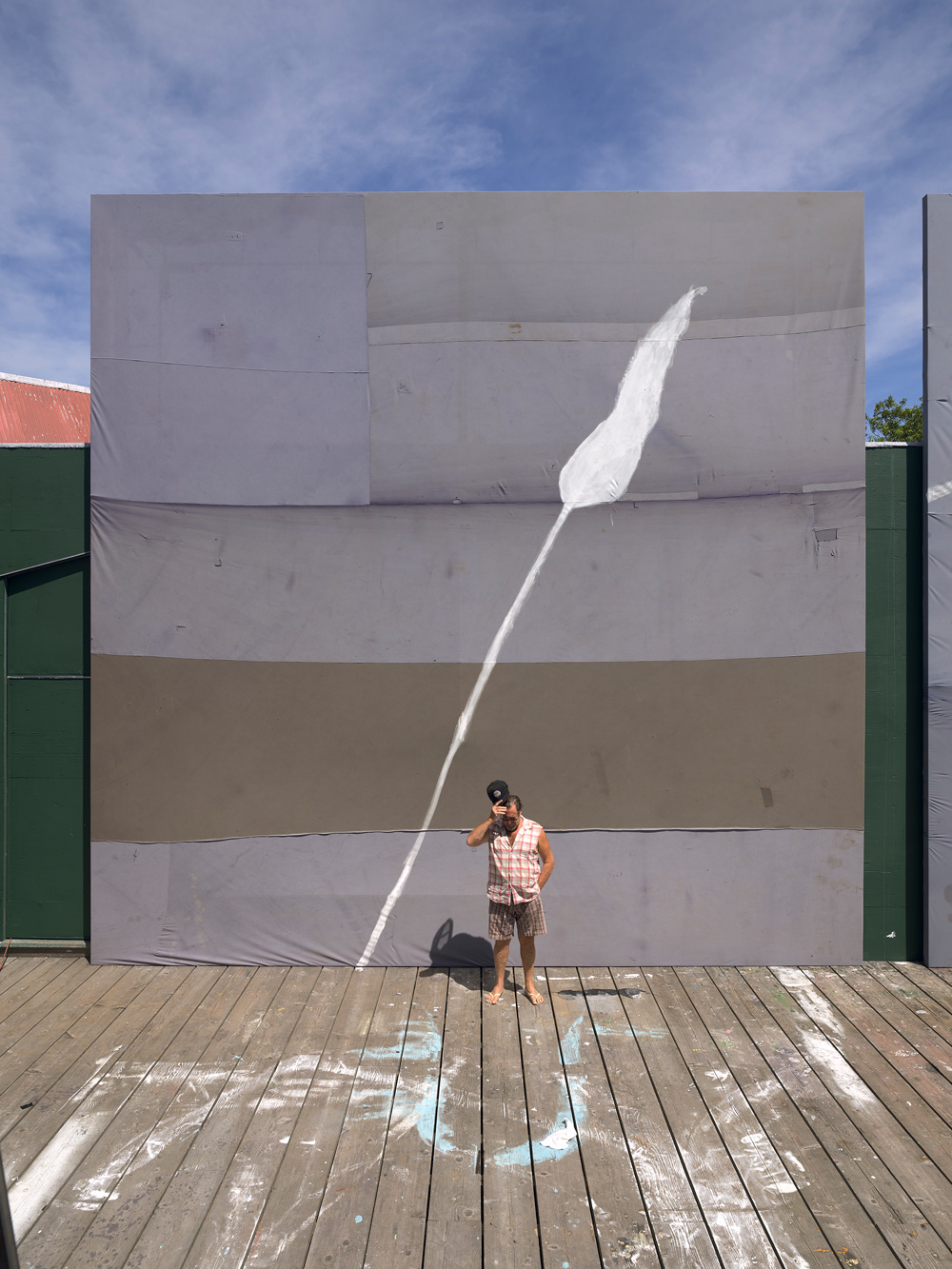

A case could be made that Julian Schnabel is the most American of painters, New York Jewish, born and bred in Brownsvillle, Texas, where he discovered Mexican culture and Catholic iconography. Though he felt fenced in at the University of Houston, the vast state spawned a passion for big ideas and a big canvas. Back in NYC, he entered the Whitney Independent Study Program, showing his paintings wherever possible and cooking at a local restaurant where he served and slayed gallerist Mary Boone. The rest is art history that is still unfolding. On April 21, Schnabel brings a body of work to San Francisco’s Legion of Honor. Director Max Hollein, who organized this exhibit, maintains that, “Paintings are physical things that need to be seen in person.” Fittingly, for an artist who is energized by painting outside, the first of the trio is created specifically for the outdoor court. Editor Evan Pricco visited Schnabel at his studio, and we both got a chance to talk with Hollein, who already organized the artist’s major Frankfurt show in 2004.

Gwynned Vitello: People are certainly familiar with Julian Schnabel’s name, and they associate him with the big broad stroke. What initially attracted you to his work?

Max Hollein: His paintings create a particular environment, and an important thing to say about his work is that people always comment on the scale, and I would say they misunderstand it as some kind of act of grandiosity, of wanting to do the biggest scale of all. But, actually, I believe it’s different, and he would probably agree. Julian makes paintings that have a kind of physicality and human scale, and to that extent, the works have a direct relationship with you as the viewer. By definition, because of their scale, and obviously, because of the materials that he uses, they’re really also objects, and they are architectural in their sheer existence, transformative of the space that surrounds them. It’s something different than a painting by an artist who kind of uses it as a window to something else. I think Julian’s works always kind of embrace you. They immediately transform the space they inhabit. There is also the very simple observation that the larger his canvases, the more reduced his pictorial language and painterly gesture get.

Can you compare that to another painter?

The exact opposite approach can be seen with artists like Mark Grotjahn or Mark Bradford. Bradford’s become more detailed, multilayered, simply full with a whole lot of paint and pictorial ideas as they get bigger. Whereas Julian’s work, well, it gets to the point, even more reduced. He has a very good way of dealing with proper scale and what he wants to convey and express. It’s an extremely persuasive and moving physical and psychological environment that he is creating. I think he has shown with his art that he can apply that artistic sensitivity to very different areas. Of course, there are the movies, but also his environments; so if you go into the Gramercy Hotel in New York, the interior of which he kind of reimagined, you are entering rooms designed by a painter.

But he became famous from the plate paintings, and those weren’t minimal.

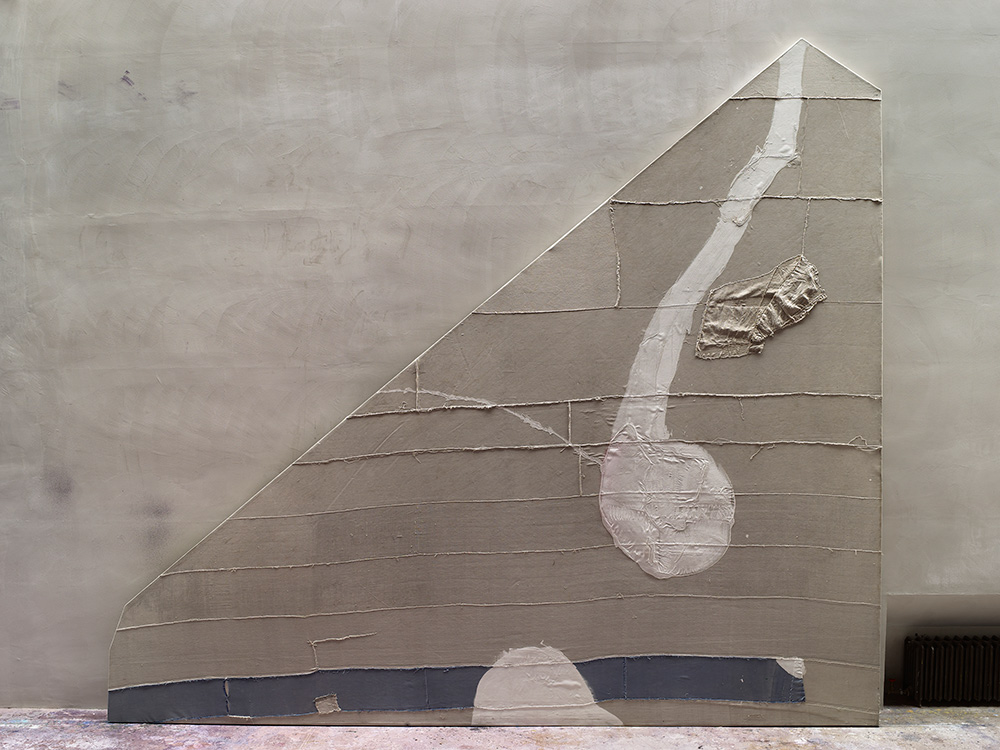

I would certainly not call Julian Schnabel’s work minimal, but if you look at the early work, which was already extremely radical, and we’re talking about pieces from the late ’70s and early ’80s, the so-called wax paintings, he was basically painting with wax, which is a very old Masters’ technique. The paintings, again, were like objects because these were not flat planes, and then what he did with the plate paintings was that he expanded the canvas even more into three-dimensionality and transformed the existence of the painting as something that does not live solely on a flat plane, but has a presence, a volume and an inherent complexity. There were, of course, numerous influences, but I think the plate paintings really created a base and established a complex representation of the world on which the artist reflects.

Though he doesn’t need to be categorized, he is considered both a figurative and abstract painter, right?

Some of the paintings are obviously very figurative in the sense that you can decipher what is being shown. But Schnabel’s work always oscillates between reduced, gestural abstraction and some figurative elements, and I think you see that through all of his works. There is no real sense to try to categorize them one way or the other. If you look at the more recent work, you will, again, conclude that differentiation is not important. In a sense, there is also no definition for a thought, a memory, an emotional status, a word. Is it figurative or abstract? It is, of course, both, and none at the same time. In a certain way, the past, things that already happened, are also figurative components, and he incorporates them by including materials or using textiles as a surface in the work. He also blows up found footage materials, like photographs, as the starting point, and then adds a painted gesture.

Like the goat paintings?

Exactly. They’re another example, and we could cite numerous other groups of works. In any event, for whatever reason, people still look at his work mainly through the perception of the plate paintings. For some, it is possibly the only thing that they really looked at. And this is a fairly uninformed position regarding Julian’s general reception as an artist. If you were to poll the art world and ask what people think about him, you get mixed responses.

Either the greatest painter, or the worst.

Right, and then what you encounter is that basically a lot of people who have a particular opinion have not actually seen much of his work. So you have this fixed notion, which is more of an opinion about a vague idea of his persona or reputation, and I would say that a lot of those people have not looked at this work in a long time. On the other hand, I think that Julian is fairly influential for a new, younger generation of artists. The most obvious is Oscar Murillo, but you have a whole other set of artists. And it’s not the plate paintings that are the big influence. It’s really the work from the ’90s and onward, as well as the very early work, this absolutely stunning, emotionally and poetically charged, yet reductionist, large kind of canvas.

Having been involved with his work for quite some time, it's very interesting that a whole number of people have formed such a strong opinion on fairly little information or exposure to the work. When I look at Schnabel’s oeuvre, I see one of the greatest and most important painters of his generation. We arranged a big retrospective in Frankfurt which then traveled to the Reina Sofia in Madrid, and I have written about his work a couple of times.

It seems that, though he’s exhibited in Europe, here he is remembered for parties and celebrity.

Well, at least from a certain group of people, and yes, it’s for them that he became the poster boy for something excessive that they see connected to the art scene development of the 1980’s. On the other hand, he has a large and loyal following of collectors, though surprisingly, there is less exposure to his work here in the US than in Europe. Even if you have a negative opinion of the work, people will admit that he is one of the defining artists of his time. So, in a sense, there is an intriguing nuance about the perception of him.

And people might just think of him as the painter who also makes movies.

Again, after his major achievements in this medium, some people try to pigeonhole him; “Well, he’s an okay painter, but the movies are great.” I would say that, regarding the movies, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Before Night Falls, in particular, though there are differences, of course, they are extremely painterly—poetic, experimental, spontaneous and persuasive. He would insist that he’s a painter doing movies. When I asked, “What did the movies really do for your career?” he replied that, “Suddenly people could start talking about what I do.” And he’s right, because it’s hard for people to speak about painting. Everyone can speak about movies and their narration. Once I moderated a panel with Albert Oehlen and Julian about painting, and it was revelatory in showing what a different language we need to use to describe artistic intention. If you would have to speak about what you like, say, about the goat paintings, it’s much harder than speaking about what you like about The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. I would say that he is the visual artist of his time who has made the best films—but I admire his paintings first and foremost.

Nevertheless, the genre is so different. If you decide to do a painting, you do it, and you don’t need anyone else. Doing a movie is a major, major organizational effort, and you need to motivate so many different people. And he can do that. If you look at his movies, especially the first ones, they’re really on a shoestring and done by sheer dedication, vision, and force of will. You can see that the actors playing in Basquiat are really his friends, participating and acting somewhat for him, so he could have David Bowie be Warhol and Dennis Hopper play Bruno Bischofberger. And he got the best out of them. He wants to use the best people, and in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, he worked with the famous cinematographer Janusz Kaminski. Obviously, this guy had all sorts of lenses, but Julian had this idea, for the cameraman to film through Julian’s own glasses. So in this very typical, impromptu way, the world is seen through his own personal lens. It’s like when he stands in front of a painting, and makes a white splash from the left lower corner, and then sees how it develops into something else. I think he uses some sort of the same artistic elements in the film medium, which usually is not as prone to improvisation.

He’s almost reminiscent of a Francis Ford Coppola, an expansive and operatic artist.

He certainly has an ego and a clear sense of what he wants to get accomplished, which I have to say, every artist should have and needs to have to basically pave through these kinds of walls they have before them. It’s fairly amazing how Julian knows things, memorizes them and points them out. He kind of digests and absorbs so much of his surroundings and is sensitive to what’s happening around him; whereas, some other artists certainly are not.

Okay, he did a film on Basquiat and he’s now doing one on Van Gogh, who are both romantically tortured artists. But he’s not tortured? His attraction to such iconic souls is interesting.

I think he has this somewhat old-fashioned idea of artistic struggle in life. I mean, he certainly shows that in his movies, although it’s more difficult to decode in the paintings. It’s very hard to make artworks that are beautiful and emotionally charged, but not be kitschy or superficial, or kind of stereotypical. I think he kind of treads on that border on purpose, which is not always a safe space.

He still does portraits, doesn’t he?

Yes, commissions and plate paintings, as well. Some might say this caters to the market, but Julian, like Warhol, has a signature style for portraiture, and one that’s recognizable for many. And for some people who want to have a Schnabel, that makes them very happy. On the other hand, I would say that Julian’s paintings, in general, given their monumental scale, their complex and coded narrative, their challenging materiality and different approaches and styles are almost the opposite of what the “market” would want.

Since the Legion will be showing some of his signature massive paintings, we’d like to know more about them.

I feel that among his most important paintings are probably the Treatise of Melancholia series. These were done for an exhibition at an old monastery, the Cuartel de Carmen in Seville; 24 paintings on olive green tarpaulin he found in Mexico. It was an extraordinary exhibition of major, very large paintings in a highly connotated environment. An element that is important about his work is that the paintings have a history already ingrained in them before he starts, so it’s not like a blank canvas. His basic canvas could be the landscapes reproduced in his goat paintings or fabric that a street vendor used to cover his vegetables. He just buys stuff that he is inspired by as the basic surface material for his stretcher, which gives his work a kind of history, a narrative. It’s already charged, to a certain extent, before he even starts painting.

Your show will feature some of these big, bold pieces, right?

When he came out here to the Legion, he kind of jokingly said, “So, Max, where are my galleries?” We were standing in the courtyard, and I played along, saying, “Well, we are standing in it.” That kind of stopped him in his tracks, and he asked, “What do you mean?” And I said, “I want to have a show of your works in the outside courtyard.”

Because he paints these large canvases in an outside studio which he built, and because his paintings are so much about architecture in their context, I thought this would be a perfect kind of environment. And with our new overall contemporary program at the Fine Arts Museums, work is not supposed to be presented in a gallery of white cubes, one, two, three, but as bold and playful interventions using our premises in an unusual way, sometimes creating tension between the classical and contemporary art context. Out of that came a new series of paintings that Julian Schnabel custom-made, so to speak, for the courtyard. I also felt we should exhibit three seminal bodies of paintings from the ’90s to show in the three galleries housing our Rodin collection. So, in these galleries, we’ll present the Jane Birkin paintings made from the reclaimed Egyptian sails that Julian saw on the Nile, the goat paintings and the abstract Mexican paintings whose canvases are from Mexican fruit and vegetable market stalls.

Paintings inspired by Jane Birkin, the actress?

The name evoked a time and mood for him. He sometimes includes in his paintings the names of people he relates to, that are close to him, or just foreign words that he just heard, words that resonate. So you will find Pope Pius IX, Ozymandias, or William Gaddis in some of his work, or his surfer friend Chuck, or something fairly mundane or haphazard in another. Again, some of it seems very impromptu, but it is about the possibility of having a reaction to the different elements that surround us, showing that all sorts of things can be reference points, inhabiting a psychologically charged room of reception. It is not a diary. It’s just him being open and applying his artistic hand to everything in life, even to the design of the chairs in his house, or in choosing an eighteenth-century piece as background in one of his works because he likes creating an ensemble for now, as well as eternity. That’s also what I really like about him.

Well, that’s the director in him.

You’ll be visiting the studio and he’ll say, “You need to see this painting. But you should see it in this light—and then in that light, and then in a third context. And he starts moving the paintings around by himself, like on a theater set where they take center stage and where he is extremely sensitive to their place and relation to the spectator.

And the Legion of Honor is his next theater. How will you take care of the paintings in the courtyard?

We don’t take care of them, I mean…

If it rains, it rains.

Right. Well, it’s not the most important thing that they’re going to deteriorate. These are paintings being part of the environment. And they will have, so to speak, that history of having been exhibited here at the Legion ingrained in them wherever they end up afterwards.

Julian Schnabel is on view at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco April 21–August 5, 2018. He is currently working on a movie about Vincent Van Gogh.