Jess Johnson

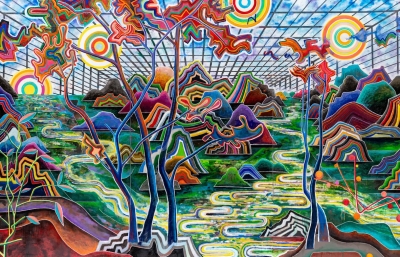

Infinite Quest

Interview by Kristin Farr // Portrait by Dexter R. Jones

Jess Johnson grew up in New Zealand where second-hand book shops and video stores were the conduit leading her to fantasy worlds and science fiction. “The cover art was always the window into that world, which got me into aspects of art and illustration,” she explains, leading to her early days making gig posters for friends, and her current endeavors as a leader in virtual reality art. Hers was the first VR exhibition commissioned and acquired by Australia’s National Gallery of Art, and it will eventually continue its travels across Australia, New Zealand and Asia. Currently holed up in her Brooklyn studio, Jess continues to collaborate with her close colleagues overseas as they develop a highly anticipated short film.

Kristin Farr: As a pioneer of experiencing art virtually, and having explored dystopic, sci-fi landscapes in your work, how does it feel to currently inhabit this fully dystopian future?

Jess Johnson: My experience is not dissimilar to most people out there, but there’s this eerie sense of familiarity combined with unreality. We’ve been prepared for this kind of world we’re inhabiting because of all the science fiction books, movies and dystopic depictions we’ve been consuming for decades, but you have to constantly pinch yourself when you’re out there. The weirdness is just the absolute mundanity of it; all the domestic routines and reversion to baking, and walks around the neighborhood juxtaposed with this very bizarre reality.

There are the odd pleasantries of your immediate routine as well. Most people I’ve talked to are kind of enjoying these times, and you feel weird saying so, but the enjoyment from cooking together, and the relief of the hamster wheel stuff that usually occupies your thoughts… everything laid on top of each other is discordant and strange.

So strange. I know you grew up escaping into science fiction, so which were your key authors or stories?

As I grew up, I found myself more attracted to what you’d call speculative fiction with different future social scenarios, which linked me to female authors like Ursula K. LeGuin, who was incredibly mind-expanding. And Octavia Butler, I got into her in art school, and she’s had quite a resurgence in the last few years. Each of her books is like a perfect gem, and her writing about power structures, gender and race was really formative for me.

There are a couple of individual books which became real benchmarks. One of them is The Inverted World by Christopher Priest, this incredibly psychedelic story about time having a physical manifestation. Another is Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban that takes place in this post-apocalyptic world where there’s been a breakdown of society, so there are small, futile societies emerging out of the rubble of the old world. It’s written in this reconstructed language, so it’s incredibly laborious to read, but around page 30, your brain clicks and you can understand it more. The idea of language reforming at the same time as a new society really got into my brain.

In your own work, you build a particular world and language. Is there a narrative to follow?

My brain doesn’t work in a linear narrative. I think of the drawings as these little pin pricks or windows into that world. My video collaborator, Simon Ward, connects those windows and introduces a bit more of a comprehensive narrative.

I’m resistant to ascribe too much to it, like if I try to lock it down or contain it, that might stop the natural evolution. In the same way, I never try to map out a drawing too much before I start it, because then I’d lose the element of surprise for myself. I do have a structured methodology in how I start composing them. There’s always the central starting point, sometimes a monument, or text, which will form a scaffolding around which everything else is built upon.

Your traveling exhibition, Terminus, has a large scale installation and five artworks viewed through VR headsets. You talked about the physical installation being like a transfer platform to the other world. Tell me more about the layout.

I think of the installations as akin to decompression chambers in spaceships, where you have to acclimatize to the pressure inside or outside. Prior to working with Simon on the animations and VR, whenever I would exhibit my drawings, I would always build elaborate installation environments of painted patterning and elements from the drawings. It’s an attempt to bring the reality of the drawings into our world.

For us, the real work is always the virtual reality projects, but the installations are the seductive, candy-coating. It’s like this false artifice meant to lure people into the VR, which they can’t document and can only experience within the headset.

The show is built around five distinct realms. Each has a location on a large floor map, with a structure that holds the VR technology. The audience is catapulted to each realm once they put on the headset. We made the VR works in a sequence, so they combine to form this transformative, hero’s journey—the story archetype where the hero sets forth on a quest and leaves the familiarity of home, then gets lost on the way there, then gets closer to what he seeks, which will be a jewel or a ring, which is usually in the belly of the beast. So that’s the way we constructed the chapters. We base things on an emotional mood.

I often come back to maps in the drawings, both Simon and I are drawn to them in some way, and I can trace it back to the books I read when I was a kid. In the first few pages, you’d see a map of the world that had been illustrated, like in Lord of the Rings or something like that, and I was always super excited by those maps. They were like an artifact from this other world, or proof that it existed.

Fleshold Crossing is where you’re crossing the threshold into this other realm, and you have all these choices of which way to go. There are all of these tangled travelators and portals transporting you to subterranean levels, up and down, and all of that. The next one is called Known Unknown, which was the respite in the journey, the chill-out zone experience where you’re just in this trippy, shifting landscape with these meta-realities loafing around you. Gog and Magog is housed in this big tower, which raises you up on this vertical platform, a big floating sphere at the summit of the tower, which is a big sack that holds all of these floating bodies, and it’s guarded by two humongous spiders, Gog and Magog. It’s the experience where you’re entering into the belly of the beast, the heart of darkness, and that’s the scariest of them all. My favorite is Tumblewych, which is basically a psychedelic experience that is really overwhelming and stimulating, and we based it on the nightmare boat scene from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. Instead of going through a tunnel, you’re going through the body of a giant worm, and all these trippy things are flashing by as you move at greater and greater speeds.

The worm is one of your main recurring characters.

I think the worms provided this relief from the really rigid geometry, the same way I started drawing the humanoids and faces of the alien deities, which are the only other organic shapes.

There’s something I started to ascribe to the worms, in terms of their function in the world or how they interact with the other characters, like they’re the physical manifestation of knowledge. I draw them passing between different orifices of the humanoid creatures, or being regurgitated or absorbed, so I think they hold the knowledge of the alien civilization.

You’ve also referenced tapeworms, which I remember from middle school science class—many jokes and fears around tapeworms.

I definitely have a pathological horror of worms and parasites, so I think I’m just playing out those deep-psych universal fears we all have. There’s a type of worm in Papua New Guinea, and I’m not sure where else it lives, but when it’s in your body, a symptom is these sores on your limbs where it burrows into the surface of the skin. To remove it from the body, you hold a match to the wound, which pushes the worm to the surface. You have to very gently draw its head out, then wind it around the match to continue drawing it outside of your body. It would take a couple weeks to extrude the entire length. It’s just fucking horrific.

I wish you didn’t tell me this! Is it real?

Yes. I look up microscopic photos of the heads of worms and insects. They’re so fucking alien and terrifying—but very good source material.

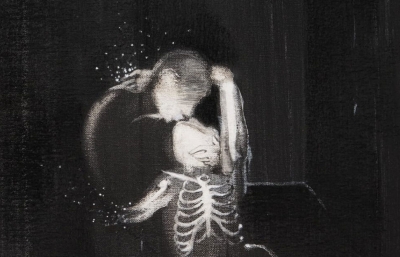

Tell me about the genderless humanoids, the “flesh suits.”

I think they became a way for me or other people to ground themselves in that world we’re creating, or mentally project themselves into it.

It’s also clear to me that they weren’t of that world. Early on, I thought of them as digital glitches, they were caught in these repetitive movements within that world. There were always positions of supplication, vaguely torturous looking, but they weren’t conscious and didn’t have any agency. Not quite sleepwalkers, but caught in some kind of digital soup. They’ve got no control in that world, and they couldn’t enact their will, and that relates to how I don’t want to give the audience any agency in the VR world. I don’t even want to introduce hand controllers, because that immediately gives them little god complexes where they want to build and conquer, or shoot, and it’s not their world to do that. So, with the flesh suits, as well, stripping them of any kind of physical identifiers or characteristics serves to neuter them.

We tried heaps of things in the first year of making VR and had to find the recipe that best fit the atmosphere of the world in the drawings. This process of experimentation and elimination created the right feeling of alienness, slight discomfort or unease, which is what I wanted people to feel.

Your new animation UmWelt conveys that unease.

That was actually the building block for a short film we’re working on. Our long-term dream is to make an animated feature film, which brings the challenge of how to translate my world into more of a narrative. That’s the struggle for both Simon and me, how to retain things that are important to us and create something that can physically connect with an audience. It’s difficult to do that with a conventional story structure.

Your VR work looks like animation but evokes the kind of feelings you get from film.

A lot of our reference points trace back to films we were into when we were young, and we got to play that out with Terminus. We could actually build our own VR versions of movie scenes that were really formative to us, like in The Neverending Story, where Atreyu passes through the two Sphinxes, and they shoot lightning bolts out of their eyes.

The other problem with making an animated film is language. I don’t want dialogue, so we are actually binding ourselves with very difficult parameters, although I was very inspired at the Moving Image Museum a couple years ago by all the working drawings and notebooks Jim Henson and his team had made for Dark Crystal. Initially, he wanted it to be told in the Gelfling language with no subtitles. I was imagining what it would have been like if he’d been able to stay true to that. There’s precedence for it.

So you would use language, but only if it was unintelligible.

That kind of opens up a can of worms...

There you go with the worms again.

There’s definitely not going to be human language...

Tell me more about how you and Simon collaborate.

The first time I saw an animation finished, Simon had been working on it intensively for six weeks, and he wanted a reaction from me, but it honestly felt like the most natural thing in the world to see my drawings animated. I was like, “Oh, yep. That’s what it’s supposed to look like.” The drawings were just renditions of something bigger that was living in my head, and to have Simon bring that out in the world just felt incredibly natural. We’ve been working together ever since.

We got a grant to buy a developer kit for the Oculus Rift and made our first VR experience, which got shown at a big museum in Australia, which was before the first consumer model of Oculus was available. For most people, it was their first experience with virtual reality, and it was satisfying to see how viscerally people responded to it, and also imprinting my artwork on their first VR experience, which can be really memorable.

Showing drawings in a gallery is this passive relationship you have with the audience, where you can walk past a drawing or painting and choose to look at it or not, but with VR, when you put the headset on someone, you fully capture them for five minutes. I had never had that feeling as an artist, of creating these really emotional experiences for people. And seeing people get super scared and take the headset off, or get emotional and cry—it was addictive.

It seems VR art can be most meaningful when it has a significant analog component.

It’s that Frankensteinian touch. If you create a world that’s entirely digital, it can feel lifeless or cold. In my work, the human hand is still visible in the VR world we create, so although every mark of my drawings is rendered digitally, it has that spark where all the flaws, mishaps, mistakes and mutations gives it this organic growth.

You use really unforgiving mediums, so I figure you never make mistakes.

I make different rules for myself, and one of them is that if I make a mistake, I have to integrate it into the drawing, and that becomes a problem I have to work through. It can be the worst thing having to solve a mistake, but it can occasionally be rewarding, because, in breaking through to that other side, I’ve given myself some new tool to add to the armory of techniques. Committing to things by inking physical paper creates a restriction, but also a way to evolve. There are hundreds of mistakes in every drawing, and when I’m in the middle of them, I’ll obsess and get discomfort or pain from mistakes, but once I’ve sent it to the framers and I can’t touch it any more, then this emotional disconnect happens. Once I’ve created the image, I can do whatever I want with it, and I don’t actually feel any ownership or emotion towards it once it’s finished.

Tell me about your mother’s quilts and your recent collaborations.

I’d never paid mum’s quilt-making much mind. It was always something she did in the background. All that piecing and arrangement, and cutting of the materials—I realized well into my drawing career that there were parallels with how mum composes her quilts, and how I compose the drawings, down to the elaborate borders, the geometry, and all the math that goes into it.

All my drawings have a high-res scan, and they get cannibalized into all these digital component parts for the animations, so there are huge archive folders of columns, limbs, alien faces, archways, and stuff like that. I come up with new digital compositions, and then I get them printed on cotton and have the material sent to mum in New Zealand, and then we work out the compositions further together over Skype. She’ll have ideas for borders, and the new ones that have a lot of applique and floating elements. Just as with Simon and Andrew, I really respect her decisions as the artist. We only disagree occasionally.

My mum’s 71 and she’s been making quilts for 50 years. She’d always made them for family and showed a few in community art exhibitions, but for her to have the experience of seeing her work in galleries and museums has been wonderful. She’s never gotten any external validation for her work, and now she’s got Instagram followers and we’ve been interviewed, and she feels so much pride and gratification seeing her work in magazines and selling the quilts. She opened her own bank account for the first time and bought a sewing machine, and we took a trip to Melbourne together to see the quilts in a museum there and have lunch with the curator, so it’s been very rewarding and special.

That’s lovely. Your drawings are the root of many other productions, and we haven’t even talked about the music yet.

Andrew Clarke creates the soundtracks for our VR and animations and is one of my oldest friends. He’s the only person I’ve ever wanted to make the music for the work. We’re all around the same age, we grew up in small-town New Zealand and have all the same reference points, and similarity in how we work. All of us have complete autonomy in respect of the parts we make. We get together and have these hot-house periods where we’ll generate ideas, and then we go off into our little work holes. It’s a seamless integration of all parts because we’re all going in the same direction naturally. We all live in different countries. I’m in New York, Andrew’s in Australia, and Simon’s in New Zealand, so we’ve got isolation and working remotely down pat.

Do you have lots of inside jokes?

We do laugh a bit. Simon had been trying to come to the States for the last year to work on the short film together, but his visa kept getting denied. He finally got awarded the visa, and we were going to present our work at SXSW, and, of course, that got cancelled last minute; but he still had this flight booked, so he came to New York instead.

Everything started escalating and going into lockdown the day after he arrived, and he was understandably worried about making it back to New Zealand before the borders shut down. So we spent this really weird eight days together trying to storyboard this short film. I live in a tiny apartment in Redhook, and we spent 24 hours a day trying to write a script and having burbling conversations about labyrinths, puzzles, keys and unlocking doors. There was a lot of hysterical laughter on both our sides. And then, every so often, we’d jar back into the weirdness happening outside, the global pandemic...

What do you most want to evoke with your work?

A fracturing of people’s psyches, or this feeling of slippage, like creating a fissure or disconnect, and then whatever space it opens up, or whatever emotions it evokes within people, that’s their own thing to bring to it. I’ve never wanted to be too didactic with whatever messaging I have. I just want to jar people out of complacency or just evoke potential for something else.

How do we get into your world and escape this one?

Restating the potential of human beings to imagine a different world than the one we’re currently living in is the first step. If we don’t have that imagination, then the potential for changing our circumstances dies as well. Imagine the world that you want, and try to build it.