Javier Calleja

Finding That Magic Moment

Interview and Portrait by Sasha Bogojev

Navigating the perplexing world of fine art, armed with nothing but sincerity and sparkling creativity, a series of odd circumstances, random introductions and unexpected events paved the path for Javier Calleja’s talent to get exposure. The story of his career and success shows modern world connectivity and the ways distant cultures follow and learn from each other. Although he was showing at galleries around Spain, the work seemed to need some sort of validation from afar to be fully recognized.

When Calleja got a chance to exhibit his work in Asia in 2017, he decided to try something slightly different. Combining a playful approach in creating installations and relatable, light-hearted imagery instantly won the hearts of the local art aficionados, turning his Hong Kong debut into a sabbatical from the rest of the art world to absorb the full potential and irresistible charm of his creations. Unrestrained by techniques, mediums, formats or scale, he began exploring this new territory, riding the fast lane into art stardom, on track with some of the most desired and collectible artists of our time.

We caught up with Javier Calleja at his Malaga, Spain studio just ahead of a successful Tokyo solo debut with Nanzuka Underground last year, and looked back at his journey through, discussing his practice, influences, and emblematic big-eyed kids in our conversation.

Sasha Bogojev: I noticed you rarely explain your works and the ideas behind them. Why do you maintain that silence?

Javier Calleja: I don't like to explain the work because I think that my works are open to the observer. So I want them to finish the painting. To start and finish. I can talk about technique, why the big eyes, why this, why that; but you need to have your own idea or emotion about the painting. Also, if I think too much about my work, then there could be a moment when I know what I'm doing. And when I know what I'm doing is the right moment to stop doing it.

Was it like this from the start?

It was difficult for me when I was a student in the 1990s because all the big artists were really intellectual. Every artwork had to have a thousand words behind it, very conceptual. So, if you want to do that, you have to have a big explanation, and for me, that was really hard to do. I wondered, "Why do I have to explain everything?" But that was the art world then, and the big artists of that era, they were always writing, always thinking, always planning, talking about the work. So I needed to find something that I don't need to explain. There is something behind my work, but I don’t like to explain it. I prefer that the viewers are the one to finish that.

Yeah, for me they feel quite simple, which gives the audience a lot of room to have opinions, because the simpler you make it, the more open to explanations. If it is done very precisely and detailed, then that's that. Is simplicity your intention?

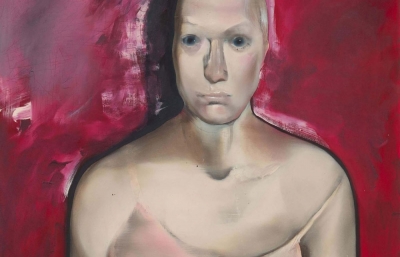

Yes. I like simple things. Simple, but not easy. I always say that I like to find a magic moment. Now, I want to do something to show you what I mean. [Javier does a very effective disappearing coin trick with his hands] It's a joke. It's not true. But, for a few seconds, or just one second, your brain says, "Oh, the magic." The next moment your brain says, "Hey, there must be a logical explanation.” But for those few seconds, it's magic. So, with art, I like this moment when the people arrive, see something and say, "Wow." This is why I like these new characters. I think there is something really important in their eyes, and it’s with only two drops, white color, and the shadows. So you get the sensation of real. But the T-shirt, background, and atmosphere are all very stupid and simple. So when your eyes notice the eyes in the painting, the brain feels like the whole image is real. They are very important to people. So your brain is looking at something real but your eyes are looking at something not real, and I think there is some kind of magic in such a moment.

How difficult is it to find that balance between the realistically rendered eyes, and let's say, a cartoonish, very flat background? That you don't go too realistic, too flat, too childish, let's say?

It's very difficult. The question is, I know that I'm a painter. I want to make a painting. But sometimes you can say, “Let's go, I can do something more realistic,” or more abstractions, but I want to be in the middle. I can paint very realistically, but also, I don't want to see myself doing realistic paintings in the future. Because maybe that is not painting anymore, something like a photograph, a representation. For example, Mark Rothko. His work is also in my paintings. Very flat paintings, not many elements. So I want to keep this moment that one part of the painting is well-rendered or finished, and other is very expressive or casual.

How much of the work is intuitive and spontaneous? How much of your process involves sketching?

I always try to do some sketches before the painting, and I also make sketches for the drawings. Then I forget the sketches and just go with the flow! For example, the bodies, the eyes, the head, they have to be a bit strange. If you do a good sketch, it's very easy to make it perfect. But in the painting, it's not easy to balance everything. Eyes need to be just right, but the T-shirt, the body, hands… I cannot think of a more stupid way to draw them than this. But not the faces, the eyes, and the mouth.

What is, for you, the most important part of the work process?

The most important part is when I feel the moment that I want to paint. I'm very Spanish sometimes, and not this kind of Spanish that I would paint only two paintings in one year and just relax for the rest. But I have to work every day, every day, every day, a lot, a lot, a lot. Because if I stop working, I stop working. It's that I don't want to work. And the most important thing is when I'm feeling that I want to paint. Sometimes, I'm painting because I'm professional, but sometimes you feel that you are painting because you are an artist. You are happy when you paint. Sometimes, you are painting, and your mind, your emotions, are all in the painting. This is the moment when you can find something new. It’s an emotional moment.

The size of canvases you are working on now are pretty much custom made, right?! How did you come to that size and format?

For the size of a canvas, I need a human size. I'm not very tall, so I need to reach the whole painting with just my hand. I did try working with bigger ones, but then I have to jump and climb things. And I want it within my reach cause it's like a dance sometimes. You need to work with something that you can manage.

You obviously have an urge, a need to produce, to make things. Is this because you just want to be creative, or is it because you have a certain message you want to send?

I do both because I found in my life that is the best thing I like to do. And I like to do things that I enjoy. For example, when I do a character, I'm not thinking about the audience. I'm thinking about me, about how to do it. I have to produce this kind of magic we were talking about. And I always follow this emotionally. But when I finish the work, I need to find somebody who will like it. The audience is as important as art. Vittorio Gassman, the Italian director said, "One actor—one spectator—the theater." So one actor without somebody who will watch, it’s nothing. I feel like the same thing goes for art—a painting without people, it’s nothing.

You always loved installations. First, they were small-scale, but now your shows are usually one big installation. Why is that important for you?

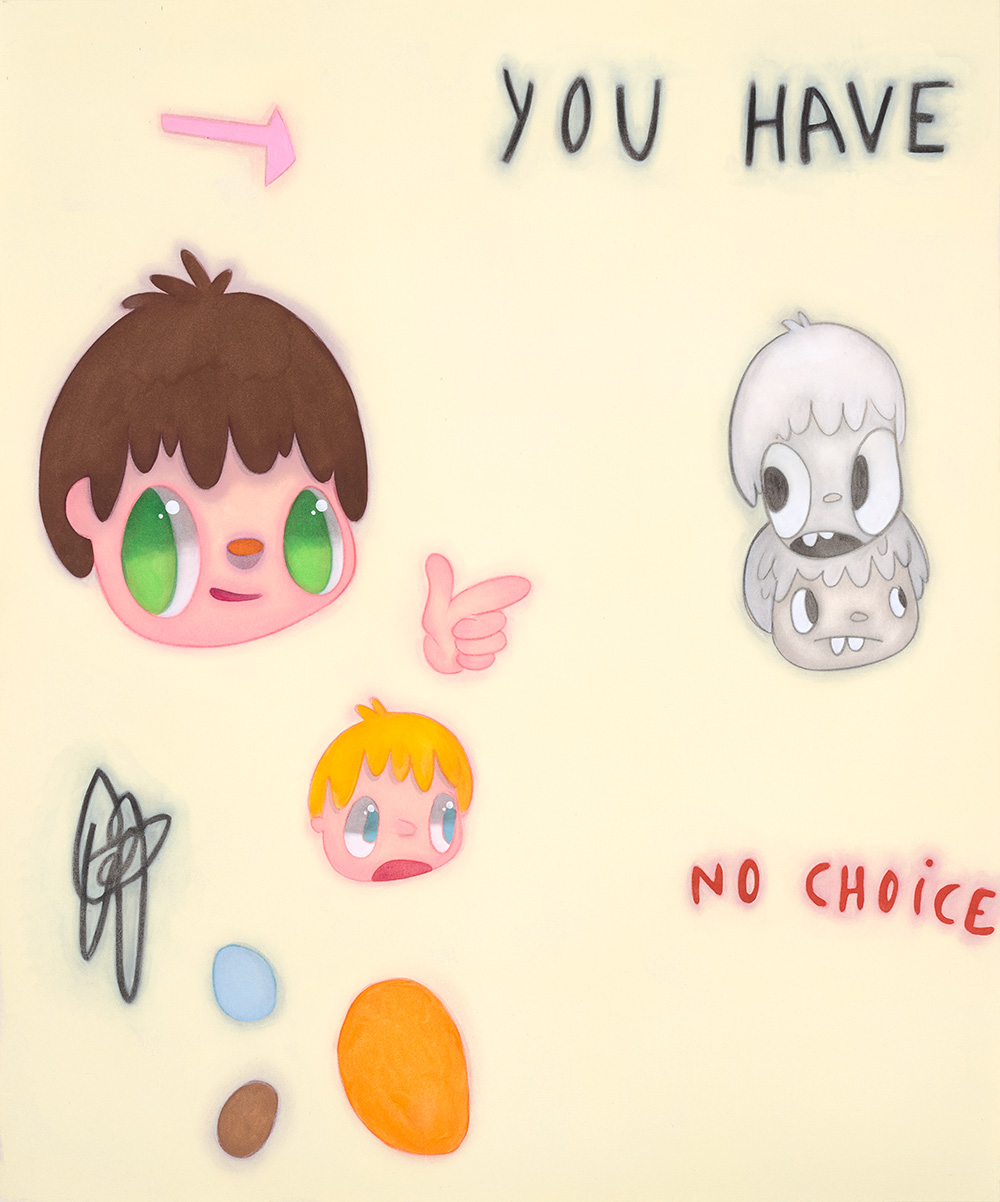

It’s important because I have so many elements from the past that I like to recover. Sometimes I do these big pencils or new characters. I like to play with the scales and make them small and big scales. Like Gulliver. Also, I had no space or possibilities to realize these big installations in the past, but most of my gallerists help me to do this kind of thing now. So I can mix the old things and new things. But I'm always a little bit worried because, in the beginning, I did small installations, abstractions, figurative, conceptual, pop, surrealistic, minimal, everything. And people would say, “Javier, you are crazy. You have to choose one.” But I want to mix everything together. Sometimes it's not Surrealistic anymore, but absurd. Sometimes I paint the character, and the text on his T-shirt is absolutely absurd. But if you mix something real and absurd, you create something new, and it makes sense, so people can understand. It's like a book—the first sentence of the book is really important.

And your style, your visual language translates great on all scales. Do you prefer big or small-scale works?

Both. ’Cause in my very beginning I used to play with scale. You know, there was a show in CAC Malaga, where I did big and really small scale, and everything worked. So with new paintings and installations, it is a completely different way, but still similar. It's still Javier Calleja. My work is now different, but the conceptual part is the same. That is actually the main connection between old works and new works.

At the very beginning of my art practice, I had a show in Madrid. When I arrived at the gallery where I was supposed to bring my work, they said, "Hey, you forgot your works. Where are your works?" I said, "No, no, my works are here, in a box, in my pocket.” The guy said, "What? Are you going to do a show with only this in this space?" I said, "Yes, yes, don't worry. You will see." And we did. With a box filled with tiny little pieces.

Do you have a dream installation you would like to make?

Yes, but I know I'm not at that level yet. So I try to not think. Sometimes I do have ideas and I try to think about the level I am at and how can I get to the next one. But I try to not think about that too much because I don't want to cry. [Laughs] My next step is to change the studio. I want to change the studio next year if I can and get a bigger one.

So, you don't have any aspirations to do like a big mural, or something monumental?

Yes, I did some murals, but I'm not happy in the street. I'm not comfortable ’cause I know I'm not a street artist. And I have never been really happy with things I did in the street. So I decided to stop. Maybe one day... but I prefer to do sculptures. If I was gonna do something outside, I have more ideas with sculpture than with painting.

What sorts of things inspire your work?

Everything. I'm inspired by everything. I can get inspired by talking with you. Maybe there is a sentence which I can use on a T-shirt. And also, sometimes I'm inspired by other artists. This is nice to talk about because, in the art world, all the artists are scared to talk about being inspired by other artists. But for me, it’s not hard to say, "Okay, if I like the works of other artists, I can try and work with those ideas too.”

There was a guitar player in Spain, Paco de Lucía, who said, "When I see somebody doing something nice, I try to do the same.” So, I wanted to do that myself. I want to repeat what somebody else made, and keep working on it. At some point, I’m doing it myself, and step by step, it's becoming mine. But at the beginning, it's the same as the source.

That’s an honest way to look at it. Which artists influence your work, and which do you look up to?

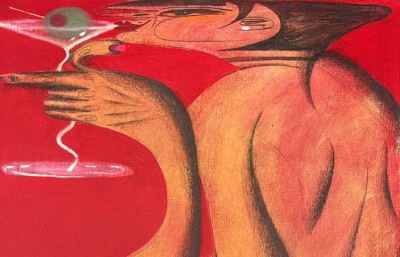

Of course, Nara, but I also love Philip Guston, Rene Magritte, and Alex Katz... You can see they all have very simple work. Well, it seems simple, but it's not, it's very complicated. And sometimes the work behind my paintings is really very complicated too. But there are many, many, many artists I get influenced by and you can clearly see a few of them. You can see very clear Nara, you can see the colors of Katz, Barry McGee structures. Many people see Nara in my work, but I can see more McGee in some of the pieces. You know, his faces, only heads. And honestly, I'm not ashamed of this. Sometimes artists are a little ashamed, but I’m opposite—I’m proud that my favorite artists are in my work. So that’s cool.

It’s great to hear you talk so openly about it. So how much of your work is focused on portraying yourself?

Every character is a little bit of a self-portrait. So it's me in each one a little bit. My mom asked me, "Javi, you can paint girls. Why you don't paint girls?" I say, "Because I'm not a girl. Every one of these is me." Sometimes I do girls, and sometimes I do something that is a mix between girls and boys. It’s this kind of age that you see a girl and a boy, and you don't know exactly which one it is. So I’m painting this kind of age maybe cause it was the happiest time in my life. That moment. When I was an adolescent, I wasn't really happy. But when I was a child, there was a moment when my sister Carolina and me, we were the same. You can go anywhere together, you are always playing, the body is the same, and that was a really, really happy time.

The first thing that comes to mind when I see your work is playfulness and positivism. And getting to know you, that's obviously a translation of yourself.

There is something in these characters. They have, you know, the eyes, puppy eyes. But it's with red. And the nose is also red. And the eyes are really shiny, watery. So these guys are happy because they just stopped crying. Do you know this moment when you are crying or child is crying, but then start to smile again?

,2015.jpg)

I know it really well—I have a four and a half-year-old son...

Yeah, so the pain is gone and then you’re happy again and this is the start of it. That is the moment I paint—when experiencing something bad and you just had a breakthrough. I think when a child is crying and then stops to cry—they’re a hero. Because he or she decided to overcome the pain.

I also see your sense of irony, empathy, a bit of a self-critique maybe, optimism, and some sort of rebellion. Would you think that these are all parts of your character?

Yes. My work is about emotions. There is a saying, I don’t know who said it, but it goes like, "everything is more important than art, but with art, you can speak about important things." So with these simple characters, only a pair of eyes and one T-shirt, I can talk about everything. I can be critical, empathic, happy. It depends. I like Philip Guston in that way, the abstract painter. One day, he was in the studio trying to mix the colors right, while there was news about the war on the radio. So he felt stupid and changed his practice, started to be a critic with the work. I know that the moment I want to say something critical, I can do that with my painting. For the moment, I prefer to be ironic.

Do you get emotionally attached to the characters? Do you give them names or have a hard time letting them go?

Yes, I do, and it happens more and more with time. Two, three years ago, I would just make the painting, ship it, make another one, ship it... And now I start to like them more and more and Alicia (my wife) often says, "Oh, don’t sell this, I want this piece.” I am a collector too, and sometimes, I am my first collector. For example, this guy with the glasses. If I sell it, I probably want to paint another one, and if I don’t, I might just keep it and not paint another one. So, selling my work and letting go is the reason to continue to paint. ’Cause if I have a lot of work I can say, “Okay, I have enough. I don't need to paint more.” But if I don't have them, then okay, let's make another one.

You're like Geppetto: just make another one. Do you repeat them? Do you have some that you made more than once in the same way?

Yeah, sometimes I try to do the same. But I cannot. I start to work with the same colors, with the same everything, but it never comes out the same.

Every character is like my son. A little bit like my son, like my child. I have no children, I have no sons. So it's like, “Okay, this one is gone. Goodbye son. Let's produce another one.” At the end of my life, I might have thousands of children.

Do you ever give them names?

No, but it's a good idea. They don't have names and I don’t know why. It’s a good question...

The eyes are quite exaggerated and well-rendered, like puppy eyes. And for me, it feels like they're a parody of this eye-candy aesthetic, or a joke. Did you ever think of it in that way?

I never thought about this. But it's another good question to think about, and I can text you back about it. [Laughs] But no, this is the kind of thing that I like—when somebody says things about my work that I never thought about. This is why, for me, it’s most important that you finish the work, because my paintings speak with you differently than with her, him or anyone else.

It feels like you often use negative space or blank space around the characters, and for me, that feels like it makes the character seem smaller and more humble. Is that the idea?

This is also another connection with my older small works. I don't like crowded places, I like having space. I always say this to people when talking about this - The biggest is not the object. The biggest is the space around.

Where do the text phrases that you use on the T-shirts come from? Do you make them yourself or do you find them elsewhere?

Yes. I try to find myself but sometimes I just hear them somewhere. In a conversation with you, or something like that. When I finish the painting I like to find the text to put there, but sometimes I don’t know what to put on the shirt. And I like to read a lot. I like to read Samuel Beckett. In his work, I can find an infinite amount of text to use. It’s amazing. But sometimes the sentence is mine. And then I make an image around that sentence.

I wanted to ask you about your experience with making these new sculptures for the Tokyo show. How did you like working in that medium?

I'm really happy with this experience. I did other ones in the past, like pencils, potato, rocks, but with my new work, characters become real. This kind of idea opens a new door. Not because the painting is flatter, but with the sculptures, I can move around. It's a new way to interact with the audience. I have three dimensions, plus other possibilities, like installing them outside, inside, etc. Also, these were made of fiberglass and metal but, in the future, I want to work with bronze, aluminum, wood, these kinds of materials. It takes a lot of time to produce, and I have to check a lot, but I'm really happy we made those.

In new works, new canvases and drawings, it feels like you’re breaking up your characters a bit. They are more like going almost to abstraction Like the text is scattered and there is just parts of the heads. Is this the new direction you’re heading towards?

I don't know. This is a moment. Sometimes I have to do something new with one painting. Just to test. At every show, I try to do something for the first time as the possible next step.

Do you think you might work more with text? I saw these drawings and canvases where the text is not attached to the shirt anymore. How might you involve it more like a visual element?

At this point, I'm considering using text outside the shirt. But sometimes, like in some of the latest drawings, I forgot to do the body. So if there is no body, the text is around the space. In these new paintings, I can use texts, heads, and color, building them like abstract paintings.

I like to play. So let's play with this. I'm also thinking that, in the future, I would like to do something more abstract with this new technique, because I find that I can do many things with this. Or something with nature, like trees, leaves, a little bit like Alex Katz. One day he found how to do trees, the landscape, the forest, and for me, these paintings are really the most beautiful of all of his works. So I'm thinking that one day I can maybe do a still life or something…

Javier Calleja will have new works presented by Nanzuka Underground at Art Basel in Hong Kong in March 2019, and he will open his next solo show with Galerie Zink in Germany on May 26, 2019

callejastudio.com