James Jarvis

The Right Kind of Wrong and The Wrong Kind of Right

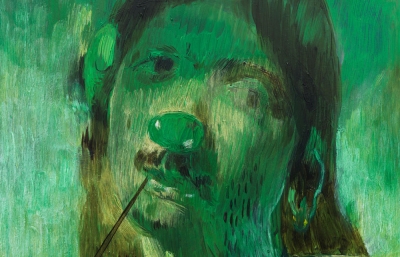

Interview and Portrait by Sasha Bogojev

It has been almost a full decade, since 2010 to be exact, when the globally recognized and popular designer, illustrator, and pioneer toy-maker, James Jarvis, graced the cover of this publication, a sagacious yellow bird in a judgemental stare-down. And while the popular art world, including Juxtapoz, has changed, checking back with Jarvis made us realize just how much his practice has evolved during this time. After years of planetary success with his Silas/Amos series of characters and toys, Jarvis decided to revisit the way it all started—by drawing.

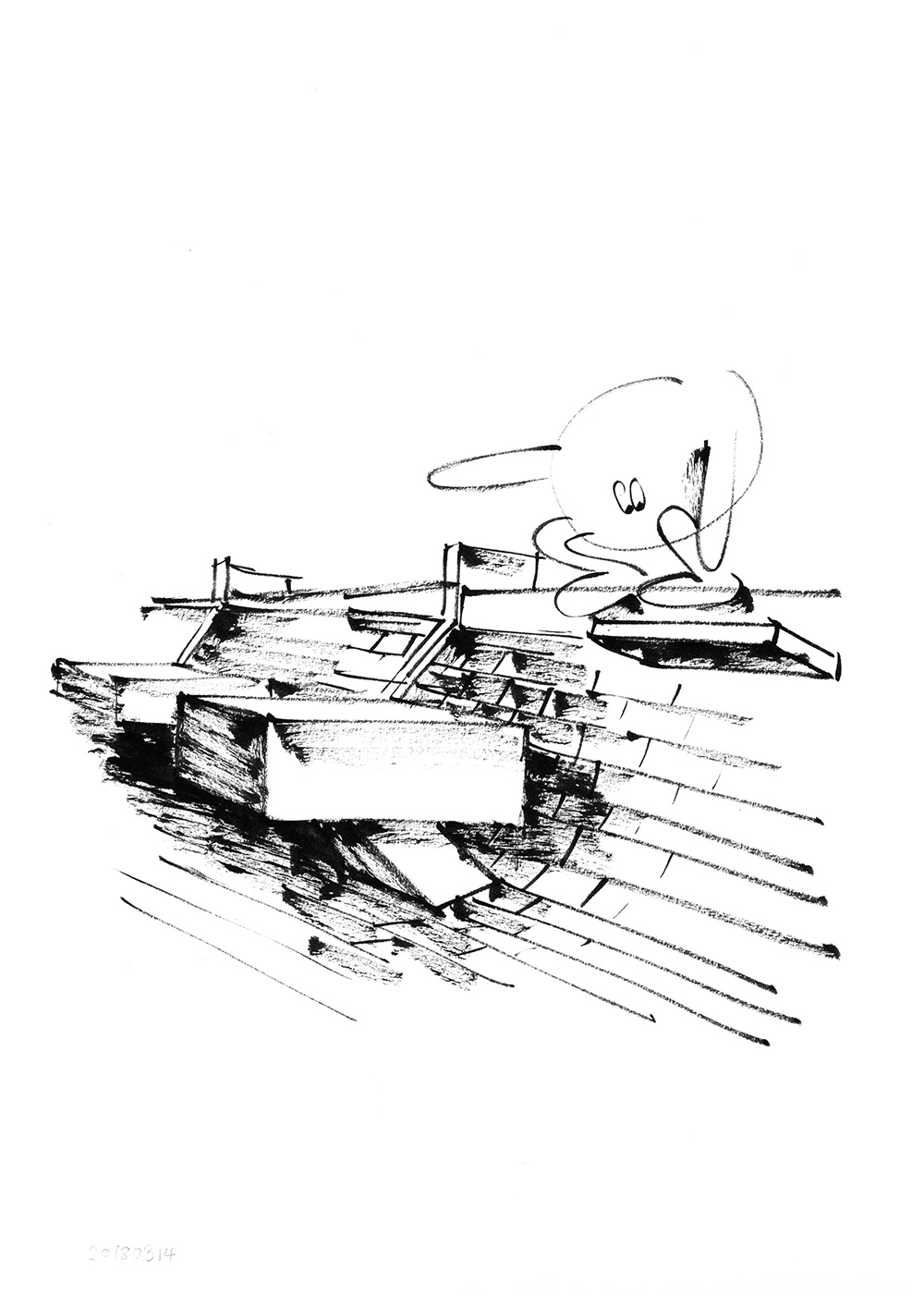

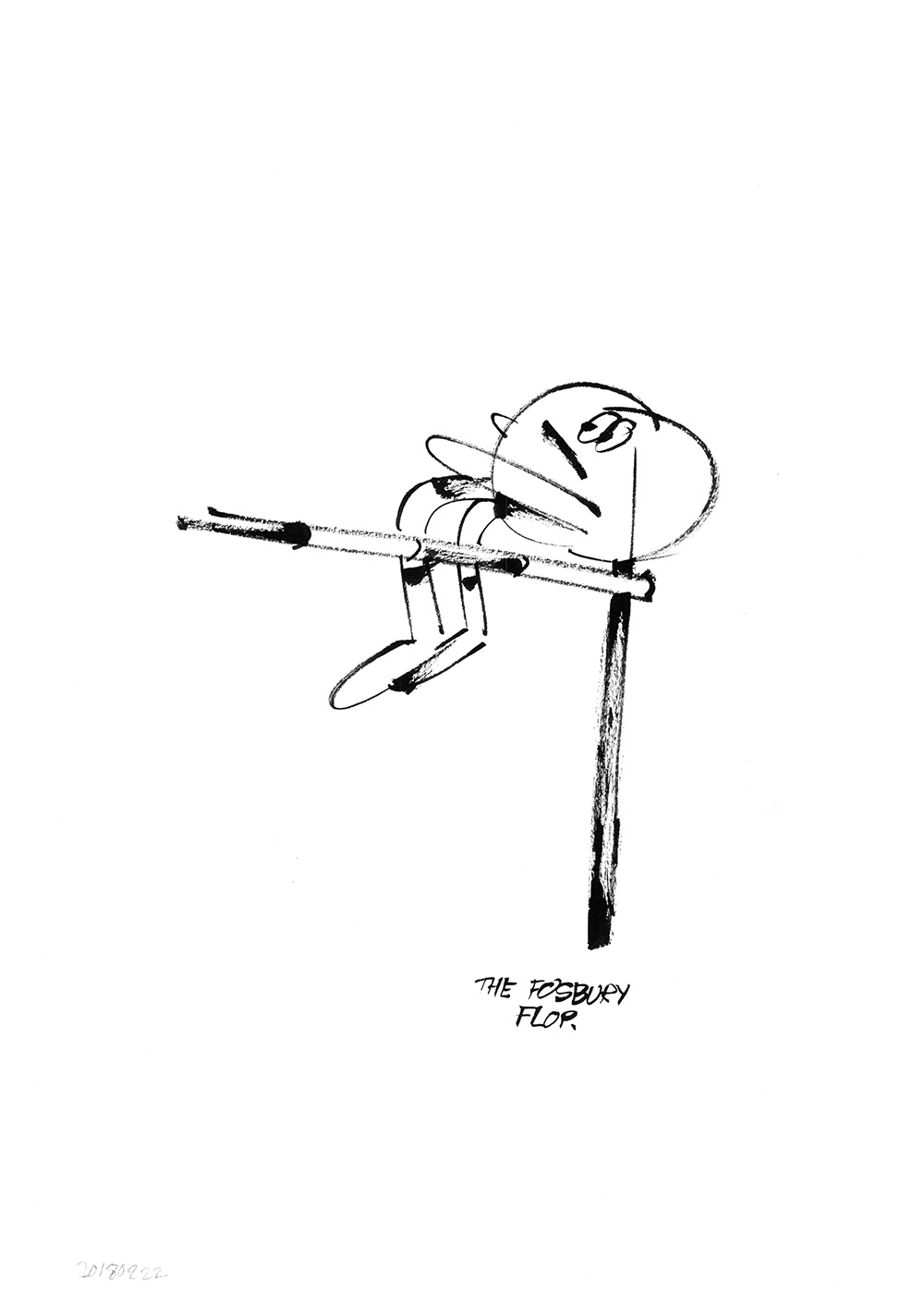

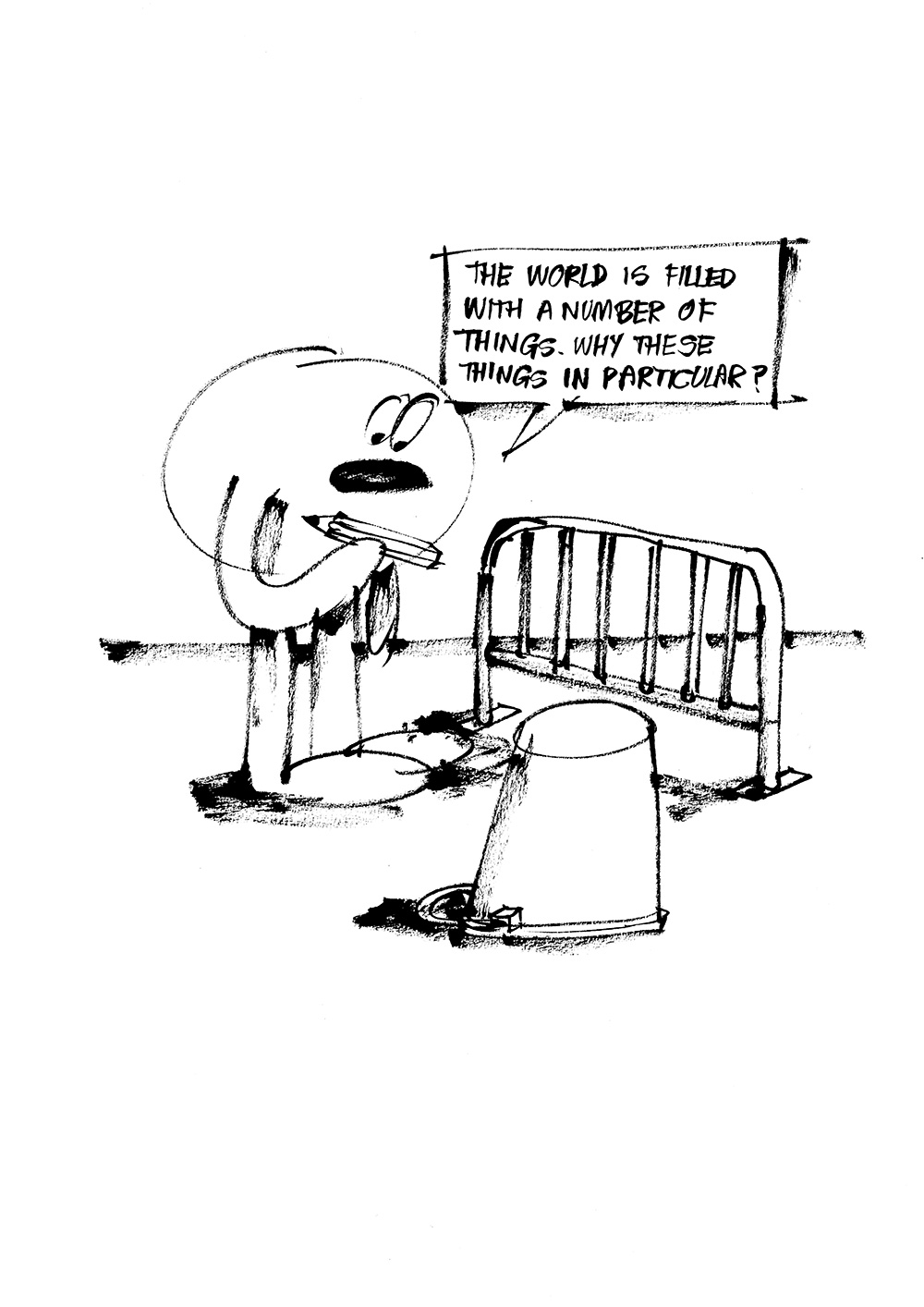

Toting only paper and pen, Jarvis took off on a mission to better comprehend the world around him. Portraying daily situations, thoughts, experiences, and references, or simply giving life to philosophical realizations, his drawings afford a deep and personal way for him to crack the code. With humor, wit, curiosity, and a critical eye, his characters battle everyday existential problems, representing all of us who ever wondered, “Why?”

Sasha Bogojev: How would you sum up what changed about your work since the last time we spoke?

James Jarvis: I think, at the time I did that last interview, I was still working with my company Amos, and my work was based on designing and making products. Since then, I’ve stopped making toys and made physical drawing the center of what I do.

You seem to have gone back almost essentially to raw drawing in recent years. What triggered that, and was it a conscious decision?

I became aware that all the work I was doing was a kind of plastic process, literally with the toys, but also T-shirt graphics, animation, everything. Drawing had become just one part of the manufacturing process. But I was aware that there was an almost sacred aspect to drawing that seemed to have been left behind. I suppose I wanted to try and recapture that.

Is that what attracts you so much to drawing?

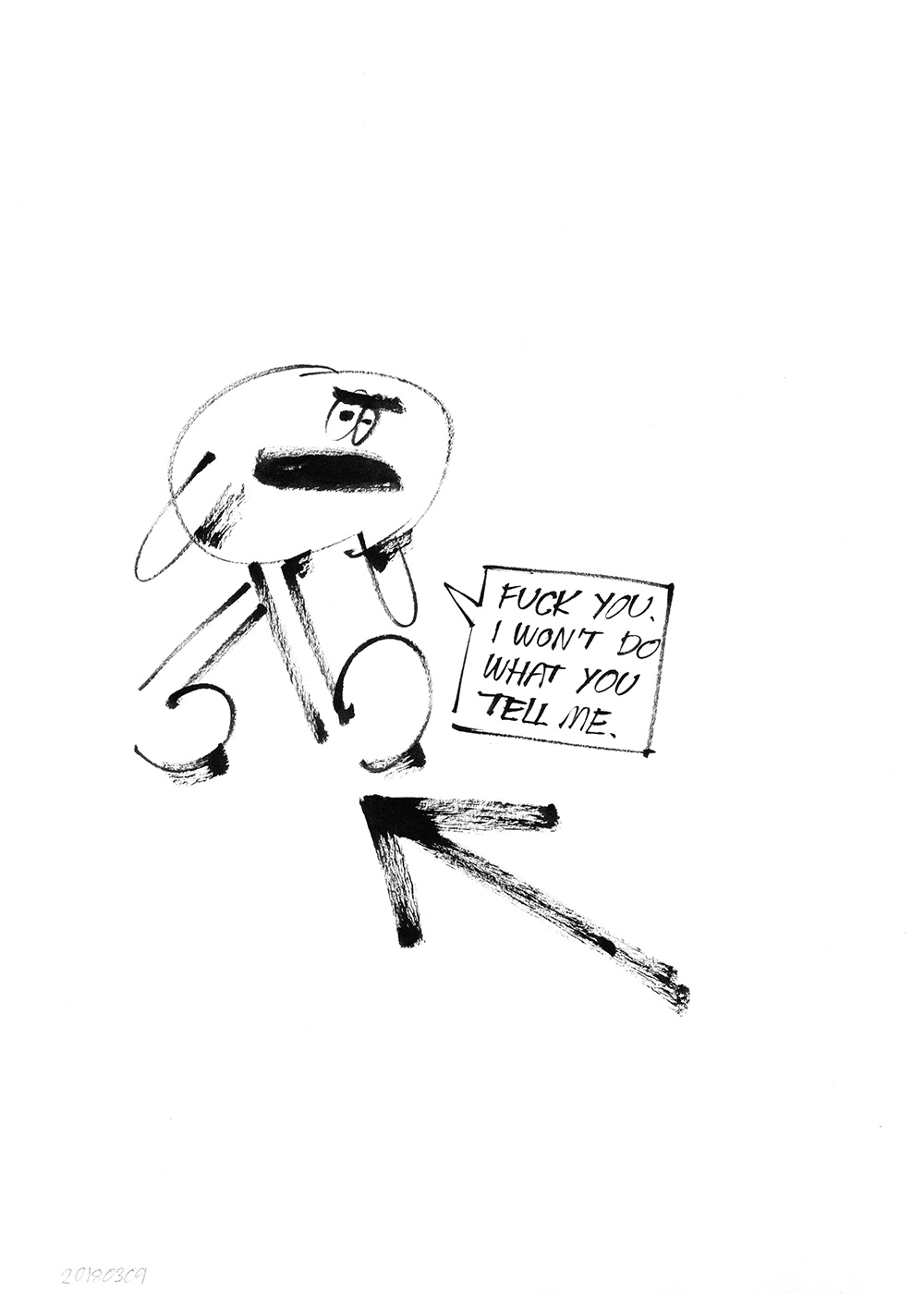

I think it is the way the process of drawing seems so directly linked to thinking. I think the value of the drawings I do, if there is any, is in the directness and simplicity of their expression. They’re not necessarily exquisitely rendered, but they are honest and truthful, and that has its own aesthetic value.

They do feel that way. How often are the drawings trashed, or do all the ideas you decide to put down on paper become a drawing with a purpose?

I would say most of the time a drawing comes out right the first time. By right, I don’t mean that there are no mistakes, but that it feels unforced and close to the original thought. Sometimes, if I try and make a drawing again, it loses the honesty of the first one, even if it is more correct. It’s the right kind of wrong and the wrong kind of right.

It's been 20 years since you designed Martin. How does it feel looking back from this perspective at those days and everything that came from it?

Designing Martin and making toys was never a plan. It was something that happened almost by accident; an opportunity to do something different that led me down a path I never imagined pursuing when I was at art school. How I feel about that work depends on what side of the bed I wake up on in the morning. Sometimes I consider that period of my work as juvenilia, as something I did while I was still working things out. But I am also aware that a lot of it is held in fond regard by many people. I do feel guilty for helping fill the world with more stuff.

Oh right, there is the environmental side to it, of course. But you've reached an iconic status with your vinyl figures and comics, and people truly enjoy those pieces. Was it hard to step away from it all?

I worked on Amos with my friend Russell Waterman, so the conceptualizing behind the company was a joint effort. After ten years, we just felt we had done everything we wanted within the context of working as a commercial entity. We didn’t want to keep making more stuff just for the sake of it, so we decided to stop. Russell had run the fashion company Silas for many years and I think he was tired of running businesses. I wanted to explore drawing and making work outside a purely commercial context.

Did you entirely step away from it for good, or did you just leave it aside?

We stopped Amos for good. We wanted the work we made during those 10 years to stay as a legacy and we don’t want to add anything that will detract from that.

How long did it take between stopping Amos and getting a first gallery show? It was the one in Tokyo if I remember, right?

Over the years, I had done small shows in lots of places, both as myself and as part of Amos, but connecting with Nanzuka was the first time, I had worked with a legitimate gallery. Not that the other places I showed with weren’t great, but they didn’t function so much as part of the larger art world.

Having entered the blue chip arena with gallery shows in Berlin, London, Tokyo, and Hong Kong, did you ever imagine yourself being a fine art gallery artist?

When I was a kid, I just loved drawing, and I wanted to do something that enabled me to make a living from that. I studied illustration at art school because that seemed the most obvious way to pursue that at the time. But apart from very early on, I never really ended up working much as an illustrator. Starting my own company meant that I conceived my own projects and my personal vision was always at the center of what I did. To a certain extent, Amos became an art project in itself. I never really imagined exactly what I would do, only that it would involve drawing in some way.

How did that shift towards "fine art" influence you and your work personally?

In some ways, it hasn’t changed anything. I try and make the work I am driven to make at any particular time. I don’t want to second guess the context I am making it for.

Was it difficult to find galleries that would show that type of work? Who are you working with these days?

It was hard to find galleries that looked on what I do as art. I think the reason I connected with Nanzuka so well is because they put me in a context where I feel really comfortable, showing with people like Haroshi, Oliver Payne, Todd James and Tanaami.

Those are some strong names to be affiliated with. Since you've always been a fan of an independent way of doing things, was it liberating to be able to express just yourself rather than design or draw a commissioned image?

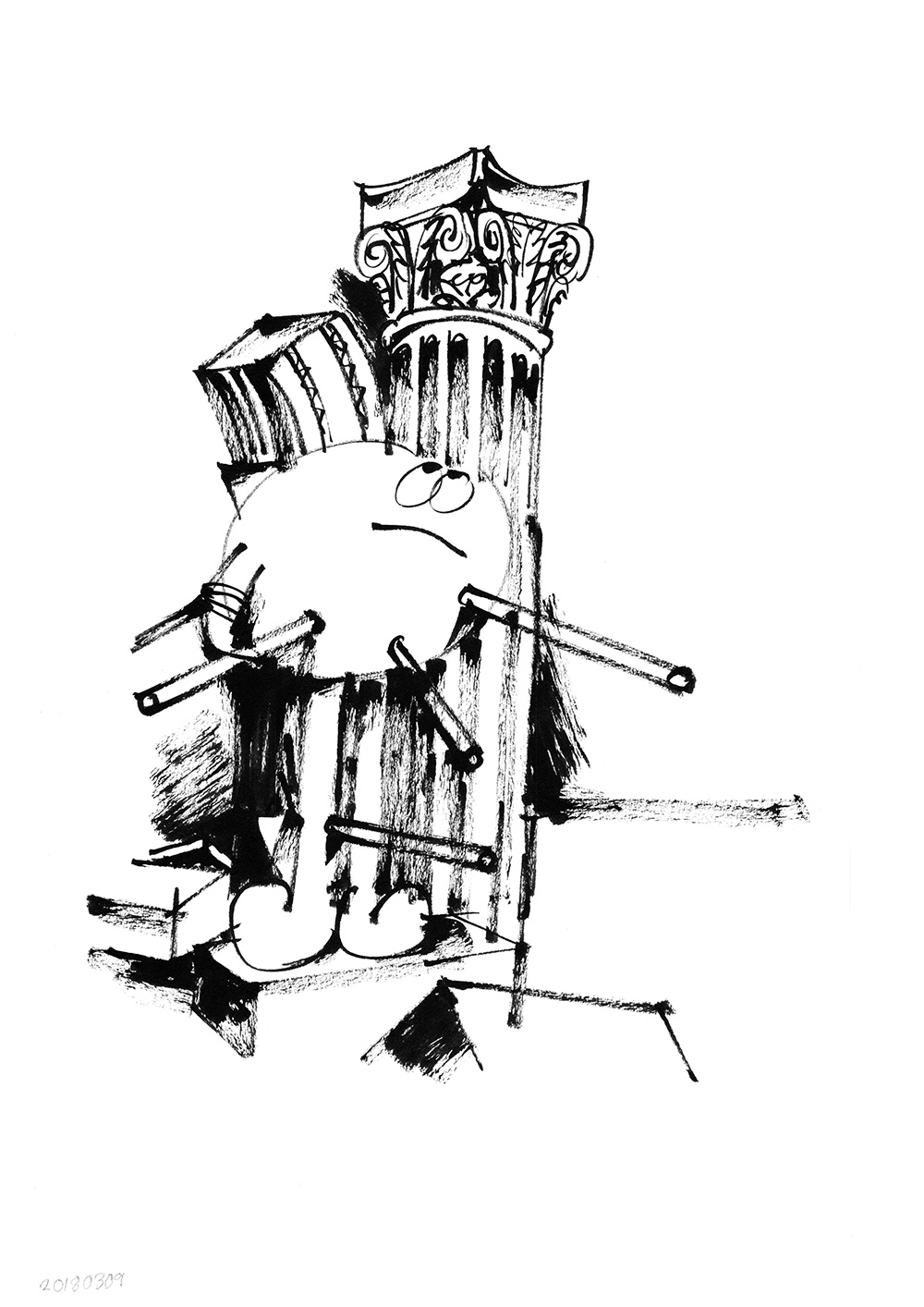

A big part of that independent philosophy came from Russell. That was how he ran Silas and that was how we ran Amos. The liberation came from not having to make stuff! I was aware that, as Amos, we made decorative objects. If the Amos work was about anything, it was about that process. I think our last project, the Amos Generic Character, made that quite explicit. After that, I wanted to make work that was about something other than itself. The first in-depth project I did after Amos was about philosophy (Spheric Dialogues) and the things I discovered about drawing from that project, like drawing as a tool, have informed everything I have done ever since.

Have you ever tried the traditional painting methods or materials?

I’m definitely a drawer, not a painter. I think in outlines. I’m really interested in artists who use process as an integral part of making their work (Sol Lewitt, Richard Long), and in sticking to a particular medium and technique, I find that my drawing becomes a kind of artistic system. The problem I find with other materials is that they detract from the system. Having a system in place means that I am free to think about content without worrying about how to go about making it.

Was it difficult to reinvent such work for white cube presentation, and how did you deal with that challenge?

It was difficult in the sense that I initially felt like I should make work that looked like the work expected in a traditional gallery context. But talking to Shinji (Nanzuka) I felt like the black-and-white drawings I make all the time without self-consciousness should be the center of what I showed.

In Hong Kong, you showed big clusters of drawings as well as canvases. Will you be continuing to work on pieces like that?

Putting the drawings in vitrines was a way of helping quite intimate pieces make sense in a gallery space. I want to carry on showing those drawings because they are such an integral part of my practice. The problem is more about other people’s expectations of gallery work.

Is this something you grapple with? How do you feel about it?

I’m always thinking about different ways to make work, but I feel that it’s important to make things that still feel a strong connection to drawing. I’m working on a couple of sculptural projects as well. I look at Haroshi’s sculptures, or KAWS’ paintings, and I often wish I could do something like that, but I come back to my process, and I think for all its faults, it is 100 percent me and no one else.

I've noticed on your IG feed the occasional use of color here and there. Is this something we'll be seeing more of in the future?

The color is there if it helps a drawing make more sense. I’m not really interested in it for aesthetic value. I do notice that colored drawings get more likes on social media, but I am not sure that is a healthy reason for pursuing an artistic direction!

Where do all the references to philosophy or science come from? Is there a certain reason why you include those elements in your work?

I am interested in all kinds of things, and so are my drawings. At a primary level, my drawings are my way of making sense of the world, and you can only understand so much from drawing about skateboarding!

Do those references influence the creation of the piece, or do you get inspired by the drawing and then include those references?

Sometimes a drawing is an attempt to record or understand a thought. Sometimes I read something and I make a drawing to try and understand what I have read. Sometimes I look at a drawing and I make another drawing in reference.

In the past, you called yourself a situationist rather than an illustrator or artist. Could you please elaborate on that?

I think that came from a drawing I made of a character saying I’m not a drawing, I’m a situation. A drawing that drew attention to the artificial nature of the process. A drawing is always firstly a drawing. It’s never just the thing that the drawing depicts. I like defining myself in absurd ways: visual philosopher, vernacular semiotician. I’m always slightly embarrassed to call myself an artist, and I’m not an illustrator, so...

What do you mean by your reference to drawing as a tool?

The idea of drawing as a tool is really important to me. I want it to be something useful, functional, to serve a purpose. I feel limited by the idea of making artwork purely for decoration.

I find it a bit strange that your work isn't more political. Is there a reason, or did I just miss a whole series of such work?

Maybe that comes from wanting my work to be about the the universal rather than the particular. I’m sure I have made drawings about political concepts but haven’t had specific references to current events. There’s an element of escapism in my drawing, and so, perhaps there’s an element of cowardice, of not wanting to look at certain things.

Skateboarding is another big aspect of your work. Do you still skate and how come you find it so inspirational?

My inspiration from skateboarding comes from the way it recontextualizes space. I do still skate, but not in a meaningful way—skating concrete parks isn’t philosophically valid!

I've found this video interview in which you mention the term "skate goggles" as something you put on when you start skating and from there, you see the world differently. How much did "skate goggles" help your professional life and was there a moment when they were a problem?

“Skate goggles” are never a hindrance. It’s like in They Live, when Roddy Piper puts on the sunglasses. It’s interesting because you end up looking at architecture and space in a different way. Everything becomes sculptural.

It sort of reminds me of the way you’re able to minimize the images to the very essence of what they’re about. There aren’t any decorative or redundant elements, and the depiction is just detailed enough to add to the whole story or concept. Was that a goal?

I think that comes from various philosophical ideas that have become important to how I think about drawing. One is the Bauhaus ethos of form follows function. The other is the Platoís Theory of Forms, which is basically the idea that non-physical, idealized forms most accurately represent reality. You can draw a particular table that you can see in front of you, or you can draw an idea of a table that doesn’t exist but more truly represents the idea of a table. I’m trying to draw platonic objects and characters!

Even your character seems like a universal archetype that fits any time or space. Why did you design it that way?

The idea of a universal archetype is important. It’s the question of the universal versus the particular again. I want a character that references as little as possible because it makes it easier for that character to represent anything.

How long did it take you to get to the character you’re using these days?

Not long. I stripped away everything from my old characters that felt unnecessary, and that was what I was left with.

Other than universality, what aspects of your work are most important to you?

Simplicity, humor, honesty? I don’t really know!

All those come to mind when looking at the work, so you’re definitely ticking those boxes. Where would you like to see your work go from here?

I would like to win the Turner Prize and generally be celebrated as a genius artist.

studiojarvis.com