Nathaniel Mary Quinn

And The Family of Man

Interview by Sasha Bogojev // Portrait by Anna Orlova-Flores

During this time when people share inspirational quotes on social media in an effort to create better, wiser images of themselves, it feels good to chat with someone who lives a genuinely inspiring story, the kind of person who not only has theories about how life works, but backs them up with amazing, anecdotal personal experiences. Nathaniel Mary Quinn grew up in some of America's toughest projects and eventually made his way to the top of the fine art world, a journey full of substantive stories. From how he dealt with abandonment and the loss of his mother, to his ability to recognize and explore opportunities, all the way to how he perceives people and their behavior, his thoughts and stories are as intriguing as his captivating paintings. Built from memories and visions, both harsh and pleasant, these parts of an unfinished puzzle nudge each other, shaping both the artist and his subjects. Painfully real, indisputably relevant, and stripped of any unnecessary embellishments, Quinn’s work proves that equal acceptance of perceived strengths and flaws makes us all stronger.

Sasha Bogojev: As you've probably been asked many times already, tell us a bit about your upbringing and about how you ended up being an artist?

Nathaniel Mary Quinn: Well, I grew up on the South Side of Chicago in a family of five. I had four brothers and I was the fifth child, all boys. We were a lower working class family living in these tenement housing developments called Robert Taylor Homes. They were kind of gang infested, lacking resources, a lot of drugs and poverty, and all that. But from as far as I could remember, I was always interested in art. I was always drawing.

Do you remember any particular moment when you decided you wanted to be an artist?

The earliest moment that I can remember was when I was copying an image from a coloring book of superheroes. I remember having this keen sense of awareness that I was actually able to duplicate something that I saw. I didn't know how this was possible, but I felt this is something that I can do and something I enjoy doing. That feeling really stuck with me.

How did your family react to your affinity for drawing?

I was always drawing on the walls of the apartment, and, of course, my mom would spank me to try to teach me a lesson. One day, I was making a drawing, and my brother Charles saw it, but when my mom wanted to spank me for it, my brother stopped her and said, "Wait. Don't spank him. Look at the drawing." She looked, and they were both very pleased. He says, "Mom, I think Nate has some real talent here, and I think we should let him continue drawing."

So that was your first studio?

Yeah, the walls of my project apartment were my first studio, that's right. I would draw on the walls, and my mom would wash the walls and would let me draw again.

Did your teachers notice your talent and give you support?

Yeah, yeah. There were these two teachers—Mrs. Filtcher and Mrs. Jackson, who were two very important people in my life. They put me in a special class with a few other students and tutored us on science, math, public speaking, art and that sort of thing. The assistant principal at that time was Mrs. Hunter, and she told me about this really cool high school called Culver Academies. But my family couldn't afford that, so the only way I could attend was if I got full scholarship. So I said, "Ok, let's do it!" and two weeks later, I was accepted.

So you stayed there for four years?

Yeah. After my first semester at the high school, I got the word that my mom passed away. That was a hit. It was so shocking that I kind of convinced myself that mom went on a vacation. I couldn't stomach the reality that she was gone.

Did you continue school after that?

I did, but one month later I went back home on a bus for Thanksgiving, and when I got home, I found the apartment door opened. There wasn't anything in there except a few articles of clothing. I haven't seen my family since. My four brothers and my dad. Yeah, that was it.

So that all happened within a month?

Just like that. And at that moment, I knew I was faced with a major choice—either I stay in that community and die young, or I go back to this private boarding high school and I just see where that road takes me.

Sounds like you were good at making right decisions and taking these life opportunities.

Absolutely! I never took anything for granted, and I still never take anything for granted today. When I'm presented with an opportunity, it doesn't matter how big or small, if I can do it, I'll do it. You can ask my wife—Quinn never complains. Quinn just gets it done. And I've always been that way. I had no choice, I had nowhere to go. If I failed, I'd be on the street, homeless. I had no family. It was all on me. Who was I gonna complain to?

How did moving to New York influence your work?

When I came back to NY, I found a cheap apartment in Bed-Stuy and I got a job painting the interiors of public schools. After that, I got a job as a teacher, working with at-risk youth, which I did for ten years. I would work until 7:00 p.m., come home and would make art in my little bedroom or whatever from 9:00 until midnight. And I did that for ten years. I would just focus on becoming a better artist.

Did the work look like anything you're making today?

Nothing like it. It was completely different. I mean, it was always figurative, but it was more natural figures, you know, straight forward, representational stuff. But I kept working all the time. I always focused on just being better as an artist.

Did you get to show or sell any of that work?

Nah, I didn't sell anything. I mean, I sold few pieces here and there, like one piece for $200 or $150, and would have two or three sales a year. But it was nothing close enough for me to be a full-time artist.

When did things start changing?

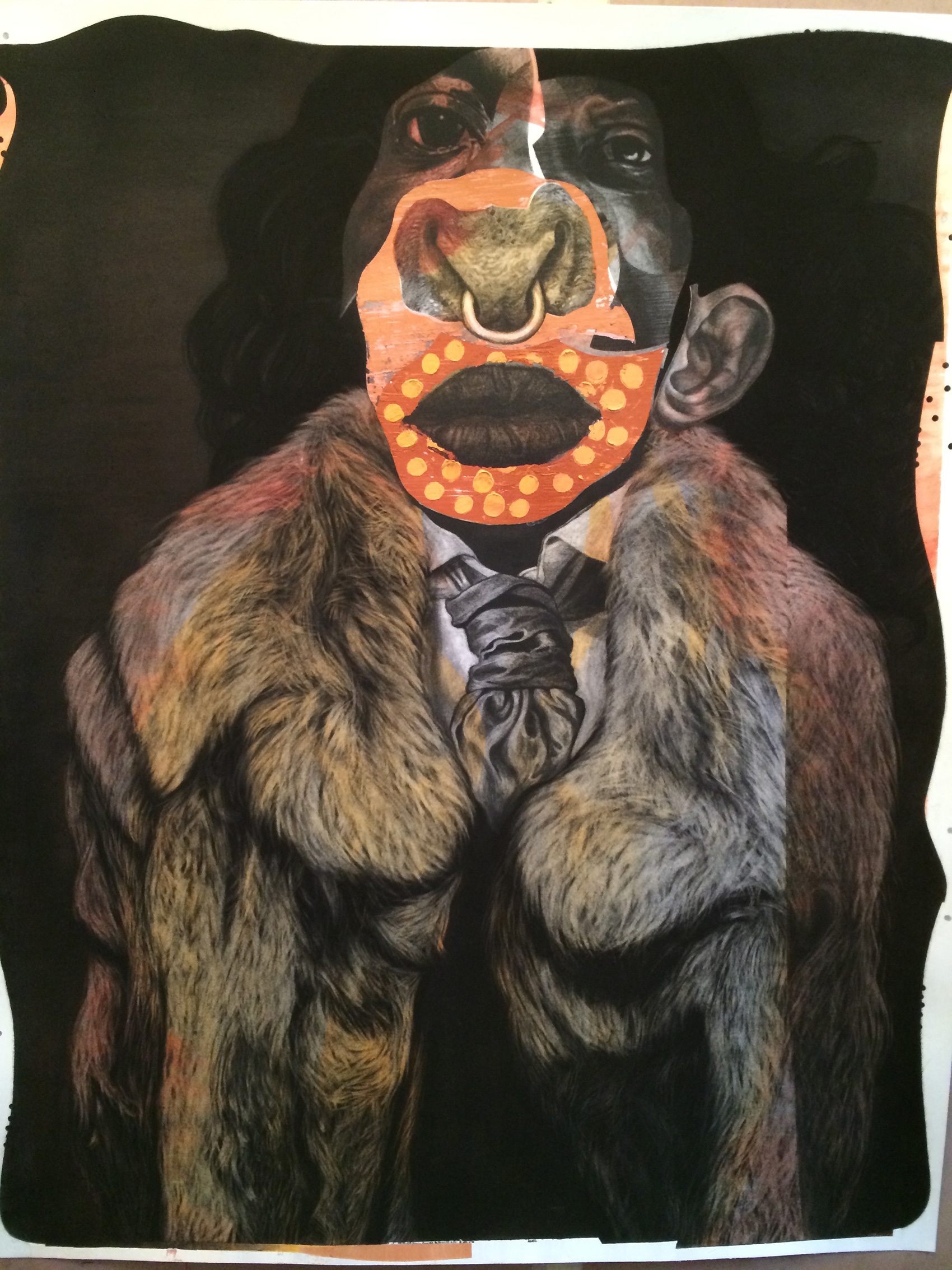

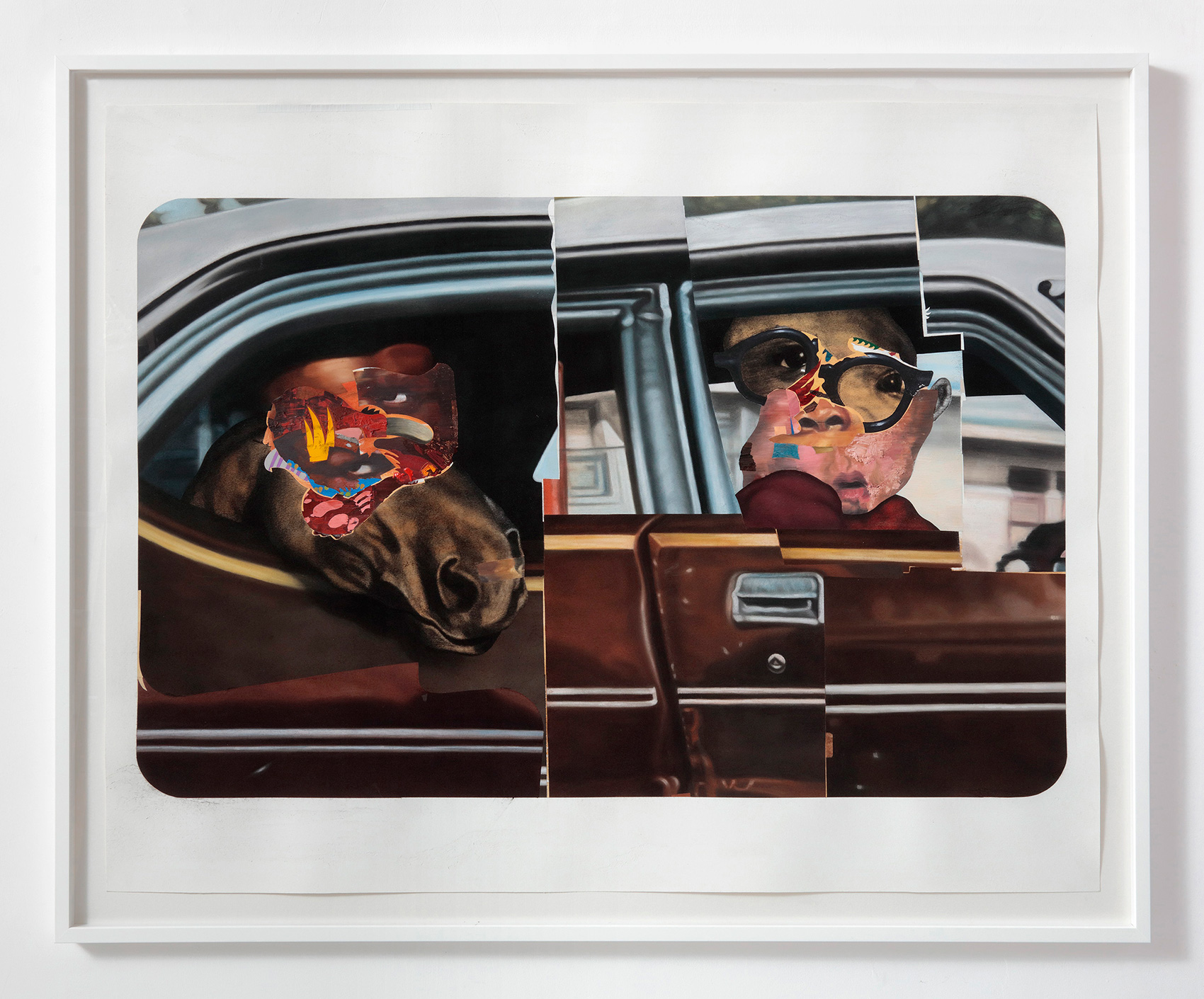

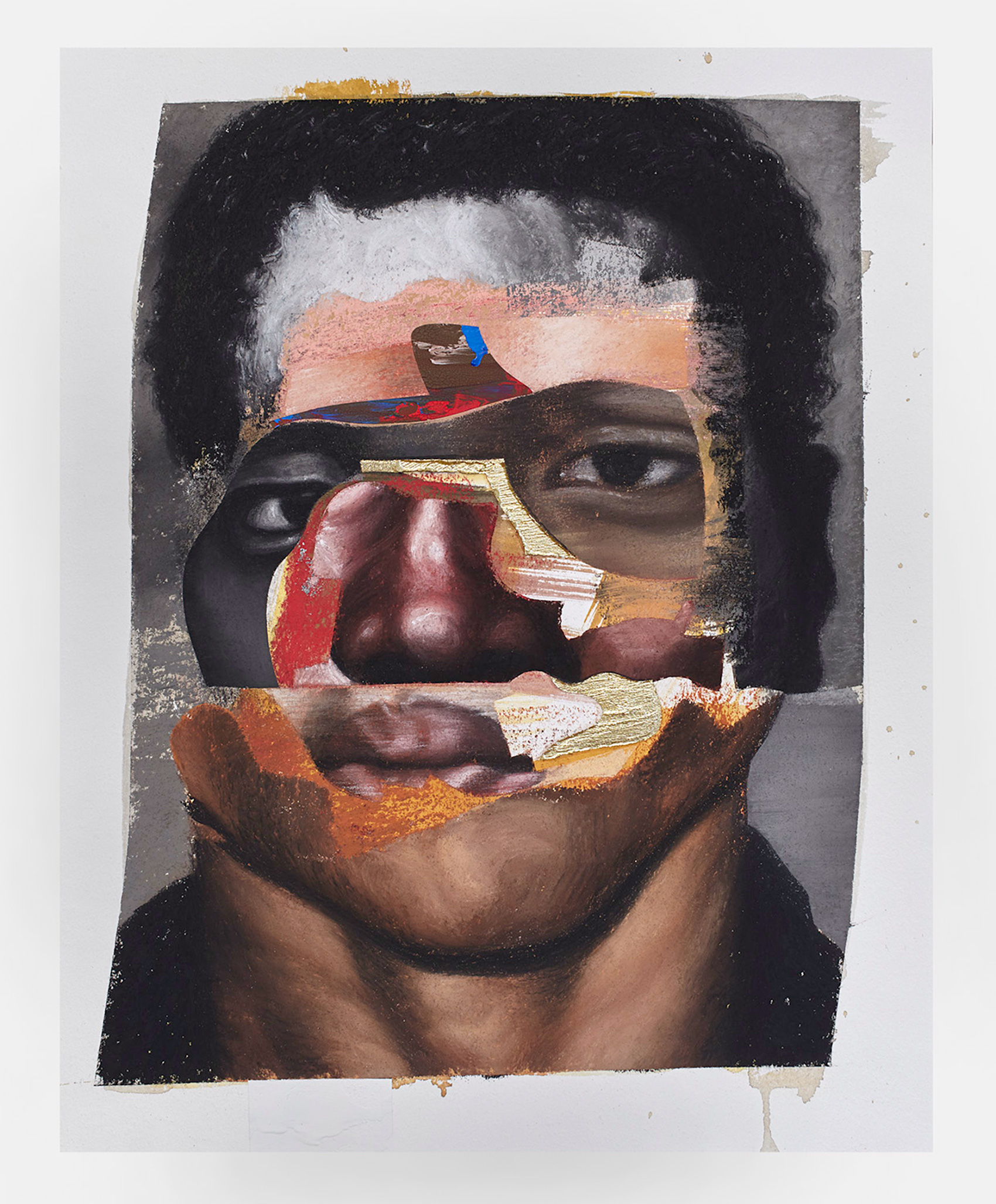

In 2012, I became a private tutor to make some extra money. There was this one kid I was helping, and his mom, Regina, offered to show my work at her brownstone in Brooklyn to help me get some exposure. By that time, I had four paintings and I wanted to finish the fifth, but I only had, like, five hours to make something. I knew I could not make a painting, so I thought I’d make a drawing. Normally, I would look at photographs and think about how they related to each other, but I didn't have the time for all of that, so rather than draw the entire face, I’d just reduce everything and focus on what's important. I'd just draw the slither of the eye and the slither of the nose, and maybe part of mouth. And I thought I'd fill in the gaps with some watercolor. And when I was done, when I revealed the whole image, I couldn't believe I made this. It blew me away! I never did anything like that in my life. Ever! It didn't even feel like I made it, it felt like somebody else made it.

Did you do it in one go?

One go! It took me four hours. And that piece was Charles. Cause it reminded me of my brother Charles who I haven't seen since I was 15 years old. And also, it was the most fun I had at studio practice. So about 20 people came to the salon, and sure enough, everybody gravitated towards that piece. Everybody! Yeah, it was like the heavens were opening for me.

Did you continue working that way straight away?

After that, I made six more of these drawings with the same passion, ’cause my conviction had changed now. When I made that piece, I didn't do any preliminary sketches. I didn't even think about it. I just worked. And the work that came out was the reflection of my brother. So that let me know that my true convictions must lie with my family. So I thought my work can be an expression of that. But also the expression of human identity and re-understanding how our experiences dictate the construction of our identity. ’Cause for me, humans look like my work. That's who we are. It was like exposing the internalized world of a person, very crudely put together.

What happened next?

My friend, William Villalongo, an artist himself, was blown away with the works. Now, I trust his reaction and his excitement ’cause I had known Will for seven or eight years, and in that time, he was trying to convince me to be a stand-up comedian [laughs]. But I'm in debt to him for life ’cause he really gave me his best to help me have a career. He put me in a group show with Susan Inglett gallery and in a solo show at the gallery Bunker 259. Afterwards, Marc Glimcher from Pace Gallery comes by my studio, and two weeks later, he calls me saying they would be very happy to give me a solo exhibition at Pace London. So my first breakout show was a solo exhibition at Pace London in September, 2014.

You recently had a show at Half Gallery in NYC that was about your mom. How did that one come to be?

The show opened on May 2, 2017, and it's like an ode to my mom and the relationship between my mother and I. My middle name is Mary, but that was my mom's first name. I took her name ’cause she never had formal education, so now all of my degrees say, "Nathaniel Mary Quinn". So now my mom has a college degree and master’s degree and her name is on the walls of the gallery, because my ultimate goal in life is to be remembered as an inspiration for future generations of artists. On a personal note, I wanna be the polar opposite of what happened to me—I was abandoned and forgotten. Now I have the opportunity to be remembered and never forgotten.

Do you have any major goals for your life or your career now?

I guess the next step for my career and life is to gather more institutional support from museums and stuff. I'm in a few museum collections now, but I wanna get into more, and do more museum shows. Also, I’d like to get more critical press on my work, and that's why I was so excited about this opportunity with Juxtapoz magazine. It gives me opportunity to talk about my work from a more critical perspective.

Yeah, it seems like your life story always takes over in your interviews.

There is no doubt that my work is about my family. But also, it's about the complexity of humanity and exploring the wide spectrum of colors of humanity. In our society, in the world at large, we have many belief systems, but what ties us together is our humanity. No one is exempt from the waves of life. We all experience loss, happiness, we go up, we go down, and we have various experiences that impact who we are and what we may become. Pain feels the same way to everybody. It's a what binds us all together. And I'm interested in exploring that. And you have to be a highly empathetic person to be able to embrace the journey with human complexity. That's why, in my work, I do images of people that I actually knew, so they become the platform from which I can talk about the larger scope of the idea about visualizing human assets. It's one thing to talk about humanity, but it's another thing to be about humanity. You learn to understand about compassion, integrity, character, loss, all because of your direct dealings with another individual. You learn to live with abrupt changes in your life and they impact your identity as a human being.

Did you feel that the current politics in the US affect your work in any way, or are you staying focused on humanity in general?

The current political situation further emboldens my work and gives it more weight. I tend to believe that Trump is in the office because he is a reflection of the collective consciousness of the American people. He is the embodiment of the social media era in which we live. Social media created the new mantra of the love of attention, and if there is one thing that Trump loves, it's attention. But he is the reflection of America at large. People are using media platforms like Instagram to express these deeply embedded insecurities under the guise of being cool, accepted and special. The reality is, though, that you don't feel special, you don't feel accepted and you don't feel cool, because you don't want to embrace who you really are. And my work is a representation of who and what we really are. And if you can embrace that, all the jagged edges of yourself, all the disjointedness, the chaos, the grotesque, the beauty, you'll be much more secure and you'll be set free.

Do you feel any extra pressure or responsibility being where you are in the predominantly white male art world?

The only thing I do have a conviction about is being a pillar of hope and inspiration for other black and brown folk who may want to have a career in art. I'd like to show them that this is possible. The bedrock of prejudice and racism is the notion of superiority. So blacks are inferior and whites are superior, right? Which is false, no truth in that at all. A superior race would be if I was walking down the street and I saw another guy just take off in flight. And he starts flying. Now, that motherfucker is superior to us! Also, to me superiority means that you are superior in every way. But that's not the case. Because if you were superior in every way, then any given white artist should be better at making art than I am. And I know that's not true. So no, I don't feel any kind of pressure to prove myself to white people or anything like that. I never felt like that. I never thought, "I need to present my best self cause who I am naturally isn't good enough."

I was thinking more about being a role model to younger kids, as you had mentioned.

I wanna be an inspiration to them so they can see there is a black guy from the hood of Chicago, whose parents couldn't read or write, whose brothers were all drug addicts and alcoholics, and that motherfucker, that nigga right there, is now rising up in what is considered as one of the world's most elite fields, fine art. Do not let racism or prejudice stop you from achieving your dreams ’cause far too many people of color have died so that I can have what I have today. People have fought for us, for the future, to get the life that we rightfully deserve, not only as black people but as citizens of America. As human beings. As far as I’m concerned, your skin color is dictated by the amount of melanin in your skin, which then can protect you from the rays of the sun, perhaps preventing your ass from getting skin cancer. It's a protection barrier for your body. That's it. Making other kind of interpretations is a dangerous slope.

Where do you see yourself in 30 years?

30 years from now? I'd like to believe that I'd be in museum collections and foundations, that I'd have a number of major museum shows and retrospectives too. I'd like to be in a position where I can have my own foundation where I can give money to students to go to school, with particular focus on black and brown students, making sure they can go to school without having a financial burden, to make an impact on the education of young people. And after that, of course, dead [laughs].

@nathanielmaryquinn