Esiri Erheriene-Essi

A Most Present Future

Interview and portrait by Sasha Bogojev

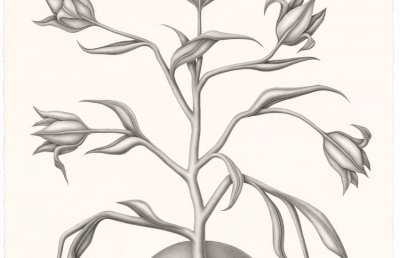

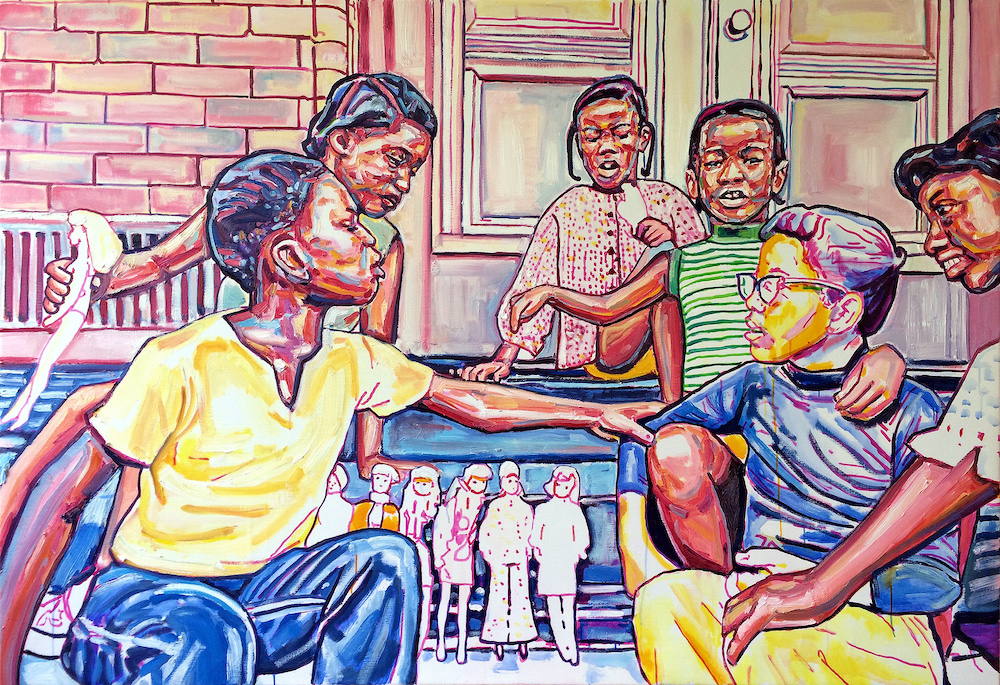

It’s impossible to feel indifferent to the tasty work of London-born and Amsterdam-based painter Esiri Erheriene-Essi. And I specifically say, "tasty," because the first thing that whets your appetite is the mouth-watering, tangy, gummy bear palette. She will then intrigue with familiar visuals of everyday people doing everyday things, teasing your perception with thick, textured surfaces marked by bold, gesture-based visual language.

Through a body of work developed over the last decade, Esiri aims to fill the gaps of a universal narrative that has often been overlooked by history. Dedicating her practice to subjects who play crucial roles embodying racial inclusion and justice, Esiri paints mostly large-scale figures of people of color worldwide. With portrayals of the most mundane of daily activities once reserved in our collective recorded history as predominantly white stories, Esiri recreates the past the way it actually looked.

Just weeks after her latest pieces were exhibited at the iconic Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam as a part of the Prix de Rome award ceremony, we talked with Esiri about the concept of her work, maternity, hoarding, and time traveling.

Sasha Bogojev: I wanted to start with the Prix de Rome award show at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. How did that come to be, and what did it mean for you?

Esiri Erheriene-Essi: The Prix de Rome came through an old tutor of mine from a residency called De Ateliers. I went there around 2007-2009, and Ronald Ophuis, a Dutch painter, was a guest tutor at the time. He's been following my work over the last 12 years, and when the Prix De Rome asked him to nominate two artists, I became one of his two choices. He just emailed me, I think, on the first of January this year and said, "I'm nominating you as my preference. Could you just give a proposal for a plan of what you would do?"

Then I was contacted by the Mondriaan Fund to tell me about an exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, and that I should submit a proposal. My son was five or six months old at the time, so I made the proposal on the phone while I was holding him. Within a day, I made a quick decision, my dream exhibition.

How did you feel about your chances of getting in?

I submitted it and didn't think anything more of it. I just did it as a favor to Ronald Ophuis. I had been telling him that painters never get anywhere, but was, like, "It's really nice that he thinks of me and of my work in that esteem, so I will do it for him."

I got the phone call in April to say that I was one of the last four, and then I had five months, starting from May, to make a whole new body of work.

While having a six-month-old?

Yes. As you know, in trying to come to my studio, I've not been working so much. This kind of forced me to really work, and I was really shitting myself actually. There were a few times where I was going to call them up and say, "I don't think I can do it. I don't know how I would be as an artist now while being a mother. I can't dedicate my 100% anymore, all of my time. I don't know if I can do it, and thank you, but I'm going to pull out." I nearly did that twice but then I just sucked it up. My mum was like, "Nope!" My husband said that we’d make it happen because it was such a good opportunity. I went back to painting and somehow, I don't know how, three days a week, I was in the studio and managed to make eleven paintings in four-and-a-half months.

Wow, that is impressive! How much did your process change because of the circumstances, and were you conscious of that?

I think I became a bit more structured, a bit more efficient with my time. I've also been a painter who paints quickly, but I’m always trying to take my time, trying to give a painting at least two weeks to a month. Now I‘m just like, "Yeah, fuck it."

It's like, I've got from 9:00 am until 6:00 pm. Those are the hours, and that's what I could do. There were some paintings that I did, three of them that I managed to do in one day. The rest of them, I had to take some time, because I have to sketch and do Xerox transferring. It's the Xerox transferring that takes the most time

I think I can see that looking at your technique, in the bold gestures and thick layers of paint. Have you always painted like that?

My favorite painter, when I first started at around 17 or 18 years old, was Lucian Freud. He's the one who got me into painting, and I loved his really thick painting, and the fact that when you were far away from the painting, it looked like just a face, like a boring painting of the face or a figure. Then, when you get up close, it was all of these abstract patterns and different worlds going on. I just kind of developed on my own, but all of my favorite painters are from the London School.

Was there ever, let's say, a "smoother period" in your painting?

I tried to, but I don't really have a refined way of painting. It's normally more emotion and energy-based. Even though I tried to be refined, the only time I could do that is if I paint super thinly. But I've never been really interested in it, more like I put my music on—and I go!

I'm not really thinking about it. I've looked at my older paintings and, in some, it’s obvious they're done by me, but they all look quite different, as well. They still have the same thick, gloopy appearance.

How difficult is it, relying so much on those gestures and work around mistakes? I'm guessing they do occasionally happen.

Mistakes are all over the place. What I have in my mind or before I paint is totally changed with the painting. As I've gotten older and more used to painting, I think I've become much more open to the fact that I can't control it. Before, I wanted to control it always, but I can't. I just kind of go with it and I don't panic as much. I just go with the flow and instinct. That's why each painting, the way that it's painted, is always different.

Does it ever happen that, at the end, it just doesn't work?

It happens quite a lot, but I try to struggle through it. There hasn't been one where I've quit, because I've gotten more confident that I can figure it out at some point. For the Prix de Rome, I don't know if you remember, there was a painting of the woman holding a child, looking back with the dresses. Her face, the woman's face looking back, that one took me nearly two weeks. Sometimes it's a mutual dance and sometimes it's a fight.

Were you always doing figures? Was that always your thing?

I started off doing only portraits, so that's how I learned. I was literally just doing portraits the whole time. Then I moved to the Netherlands in 2007, and I stopped doing them so much and started using more reference photos, photos that I found. Then it was mostly full figures. I went through a lynching phase, so I was doing lots of different things.

How do you find and select the reference photos?

They come from everywhere. I buy old JET magazines, the old African-American magazines from the '50s and ‘60s. They're mostly in black and white, but the cover is in color. I collect and buy them online on eBay, on Etsy, just different online auctions; and I buy Polaroids and Instamatic photos as well. I just buy them or save them from different online archives.

So, do you select the ones you buy according to the image or the story behind it?

It's mostly surface, it's mostly aesthetic. It's in the pose, how it looks, and the memory it triggers. Most of the time, it's like I don't really know why I select it. It's just something I like about it, then I will just buy or save it. Then I take it to the studio to find out why I'm intrigued by it and what I can act on.

When you say memory, how do photos of strangers connect with your personal experiences?

I'm from England, from London, but my parents are from Nigeria. A lot of times, when I was a kid, I was always looking at our family photos of my grandparents and their parents. That's how I learned about who I was, why I had these photos of people who I've never met. Then I would make up stories about them and attach narratives, just imagining who they were, what I got from them. That kind of spread out to other things, and even if there was no relation, I was always trying to figure out who these people were. I was just intrigued and curious by them. That was just the starting point; then it would go from there.

Do you ever research the stories behind those photos and try to recreate them?

No, because there's no information the majority of the time, especially with the photos I’ve recently saved in the last two, three years. There are not really things I can go and retrieve. There's just this one photo that's either been thrown away or sold. Sometimes there's a little note about who's in the photo or what time, but not much else.

Speaking of old photos, the first time we met, you told me about a color calibration thing with old Kodak films?

I was buying lots of magazines from the '50s and photos from the '60s, and I would always notice, especially looking at black skin, that it was super dark and super flat. I was Googling Kodak and black skin, and came across loads of articles about Kodak technology being actually quite racist because it wasn't at all adapted for black skin.

It was geared for white skin. Everything depicted was super flat and super dark. I found it quite interesting that, even with a simple thing as a camera, we were kind of erased in that sense. I wanted to play with that and use that predominantly, just to see what I could do, to see how I could bring out colors within.

Do you know when that technology changed?

In the mid-’80s, but only because, I think, a chocolate and a furniture company got really annoyed and petitioned Kodak to change it due to the way their brown furniture or brown chocolate sweets were looking. That's the only reason it was changed.

Is there a certain emotion or atmosphere you try to convey with your work?

I'm just really interested in a lot of these silent, quiet histories. I spent a lot of time going to museums as a kid, and I see the whole history of Western art and all of these portraits that are signs of people being alive, and I didn't really feel connected 100% because there were not people that looked like me.

When I look at these photos, it's a way of me having that same feeling in the museum, of all these people who come before me. I want to give the spotlight to these people, I want to celebrate them because I really think that if it wasn't for all of these people doing what they did in all of these different parts of the world, I couldn't be here doing what I'm doing now, living my dream to fruition.

It's the greatness of these people who are just living their lives, regardless of all of the turmoil that's going on around them.

And by greatness, you don't mean grand achievements?

No. It's just them living. I mean, I collect images from the end of the 18th century, up until the ’80s. I'm just thinking of all of the times, especially in the Civil Rights Movement in the US, the UK and Nigeria, those three countries. They're just getting on and doing what they have to do.

There are all of these great, famous photos of protests. But I wanted to celebrate the people who are protesting quietly. What happens when they leave the protest? When they go home and live their lives, what does that look like? These are things that I'm intrigued about and that's what I'm trying to celebrate.

To some extent, it feels like you're filling the gaps of a historical narrative that's been kind of a “saving” for certain types of people.

I think that's important. We're in 2020 and there are other voices that come to the table and kind of fill in the gaps, because there's a lot of gaps. There's a lot of discrepancies in contemporary history, especially in the West. Not all voices and not all narratives are being told.

Sometimes I can go in and re-edit, but then I'm just drawing from what has been around and trying to think about alternative histories and alternative ways that people have been living, and kind of present that—see how that relates to now and how that will relate to the future.

Did you ever use your own personal family photos?

I have used my own family photos, and my family photos are in some of the paintings, but I use them as a base. I think, going forward, I have quite a lot that I want to use, I just wasn't as comfortable before. There's a really cool image of me and my father, my aunt and cousins, when I was, like, one, in Lagos, Nigeria, for my birthday party, and I'm crying. I finally got a good copy of it because I think it was somewhere in London.

Does it feel different building a narrative around something personal, more familiar?

No, because there is still a distance there, and even though I know that's my father, he looks totally different to how I knew him when I was growing up and how I know him now. There is this kind of distance, and the same with my aunt and cousins. It's like, there is a time, of course, but there's a distance to it that I can go in and still play around with. Of course, maybe I never saw myself that way? It's just another baby, but it just so happens that it's me. I think I have more license about what I put in than if it was some other random person. I think I could go a bit more crazy with images that I know. When it's not, I think I'm more hesitant to go too crazy with suggestive images.

I read somewhere, I think the biography on your website, that you see history not as something that has passed, but as something we carry within. Can you elaborate a bit about that?

I was reading James Baldwin a couple of years ago, and I was thinking about all the things he was talking about in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, and how it still relates to now. How history is this forcible power that is all around us. It's in our names, it's in our language, it's everywhere. It's there and it does no good to just ignore it—where we come from, and where we are now, and where we're going. There are always things that I can relate to. I'm just really intrigued by that, and that's how I look at history—as this thing that's always within us and everywhere, and something that we can never get away from.

And, in what way do you think such an approach informs your work?

I go in there and I can kind of play with history. The people that are in these images, I can take them on a time-traveling adventure. I can bring in someone from the ’70s and then imagine it as originating from the ’50s. Bring in references from 2020 and kind of go back and forward with everything. It still relates to now.

Do you remember when you developed that concept?

I think the bigger shift was when I moved from London to here. In London, I was making comic paintings based off of photos I had taken of me and my friends. We would go to bars or pubs and I'd be taking photos of them vomiting, then I'd be making drawings and paintings of that. I wanted to document modern life, that's what I wanted to do. When I moved here, I didn't have them anymore, nor did I have the energy of London!

Your art is becoming more and more known here in Holland. What is it like in the rest of Europe, internationally, and in the United States? Have you shown around much?

I haven't shown in London pretty much since I left, so that's a long time. I would like to go back and show there because I think there'll be quite a great link. Same with the States. I will finally go and show at the Armory Show, so I'm going to be taking some new paintings there too.

I'm curious to hear how the work will be received there.

That will be a good gauge, just to see how it goes. I get a lot of comments from people here, especially the Americans who ask, "Are you American?" When I tell them I’m not, they're like, "Oh, because this looks very familiar. It's very American." I always explain that there are images from America, images from Nigeria and images from England."

As an informational tool, do you ever give context around your work when you have exhibitions, as in where the images are from?

I think maybe I should do that. Well, not should, but it would be nice to do that in the future. But normally no, because I take all of these references from different places and I want people to connect without me kind of imparting my intentions. One hundred percent. I don't want to block people and close them off at the bat.

If people ask me and inquire and where the image comes from, of course, I would let them know, and then maybe they can do some digging. I just always leave little clues, sometimes in the titles, sometimes in the images themselves. Then I leave it up to people to kind of go and dig in.

Esiri Erheriene-Essi will be exhibiting with Ron Mandos Gallery at the Armory Show in New York, March 5, 2020–March 8, 2020.