Edie Fake

Off The Grid

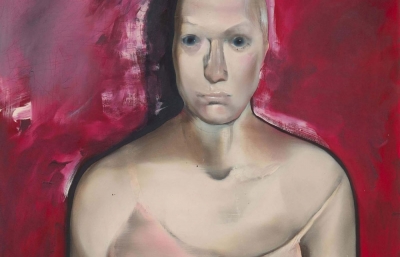

Interview and Portrait by Joey Garfield

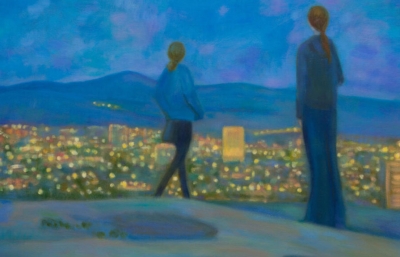

Driving through the California desert heading to Joshua Tree, the sun is ablaze and the air is dryer-vent hot. Riding along shotgun is Chicago native and art zine connoisseur Oscar Arriola. Our assignment is to interview transgender artist and activist, Edie Fake, who, though familiar to us, leaves us curious and, speaking for myself, a bit suspicious. What kind of person on such a prominent trajectory in the art world today would want to drop everything and live in such a remote area? Is he a recluse, a hermit, a danger? Why does he live down such a sketchy road, and what lurks past that bush? Our anxiety quickly diminished when we arrived and heard, “The Scorpions only come out at night, but there are sun spiders. C’mon in. Want a smoothie?” I give you Edie Fake.

Joey Garfield: Oscar and I would like to know what the fuck you are doing out here in the desert?

Edie Fake: I’ve been visiting the desert for years. When I started to make more of a living off painting, I got this bee in my bonnet that I could live anywhere… why not the desert? It’s mind-bogglingly beautiful, though today’s dusty wash may not be that astounding. The landscape is really amazing.

JG: How long has it been?

This is year three. Every year has been different. I also moved out here because I was living in LA and I needed to change my life. This seemed like a low-pressure way to do it, somewhere beautiful and cheap.

JG: How green were you when you arrived?

The first night I moved out here, my neighbors, who are good friends, were actually heading out on a trip, so they welcomed me but were, like, “See Ya.” There was a thunderstorm and my place was really shaking. There were heavy rains, lights flickering, and coyotes going off. There is a marine base nearby that was testing artillery and that shook my windows from the impact. I still had everything in boxes and my roof was leaking.

JG: Welcome to the worst idea ever. Are you able to focus better out here at least?

Oh yeah! In the city, I would start to draw and then say, “Oh, I’ve got to go get another light bulb,” or, “maybe time for some pizza.”’ It was constant distraction and I’m really bad with it. I needed tunnel vision to get things done, but out here there’s quiet time all the time if you want it.

Oscar Arriola: Do you miss Chicago?

I was pretty set up in Chicago and I miss it. Part of it was this dog fell into my life. It was so miserable in the winters there, and that was reflecting back on me how miserable I was in the winter. I was really getting blue. In Chicago, I was trying to have a full-time job while having full-time studio hours and was shortchanging every friend and relationship I had in my life and my work. Everything was at loose ends. Being out here, I can commit to people and work in a way that feels real and is healthy and not frazzled all the time

OA: Has the desert lifestyle changed your artwork?

Yeah. It’s given me room to try stuff out. I look at the work that I started when I was in grad school in LA and saw it was coming from a place of sadness and worry, and trying to draw these drawings that are puzzles and metaphors about identity that were all ending the same. Being out here kind of reminds me that things are flawed, funny and contradictory, and that’s ok. It was all a process to go through. I feel like between drawing those drawings and being out here, I can think, “Oh yeah. There is joy in life, not just conundrums.”

JG: So, in regard to your artwork, it’s very personal. Gender identity is obviously a very intimate thing. Having a surgical transformation is one of the most hardcore ways of accepting yourself and you have been very open about it throughout the process. Part of your work is being transparent but in an abstract way. Do you feel obligated to share?

Why not be open about it? It’s something people maybe don’t deal with because they don’t think they know trans people, or think, “How could I possibly relate to that?” It’s very human to have these questions and work it out with your friends and the people you are on Earth with. So I make the work personal in order for it to feel honest and worth making, especially with comics. If I don’t hit on something that I’m not working through psychologically with myself, it’s not worth doing.

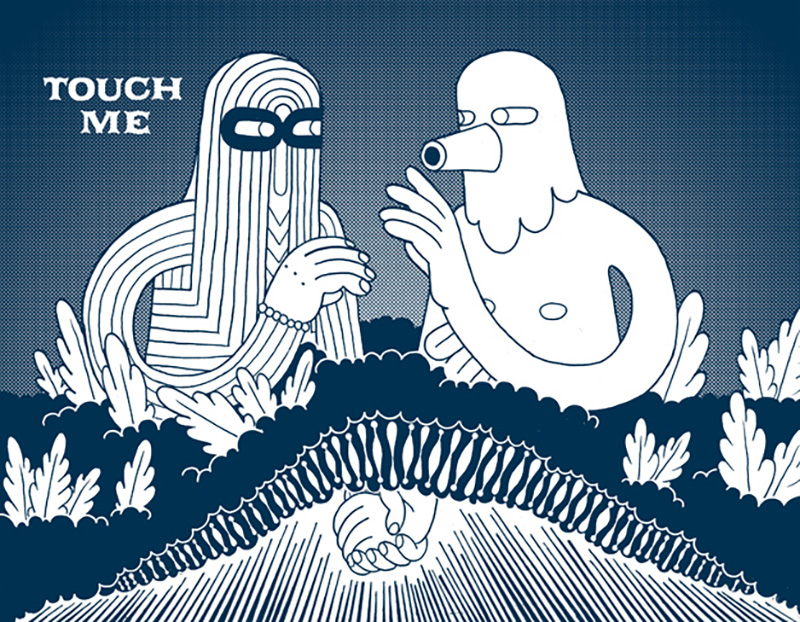

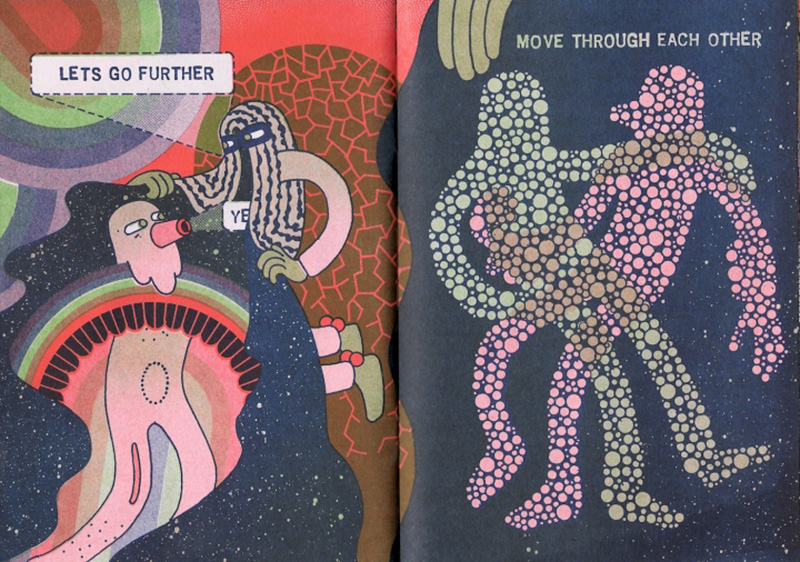

OA: Can you explain what your Gaylord Phoenix comic-zine series is about?

Gaylord Phoenix is a gender-conforming bird-man who goes through these magical environments and has a lot of lovers. There are a lot of monsters, changes, and strange friends in the process. It’s a transformative journey that doesn’t directly relate to my boring autobiography because that would be, “Dear Diary, Today I walked out in the sand and picked up some rocks.” But it does mirror some larger emotional things in my life, and that’s what I try to put in these fantasy comics.

For the first five issues, he’s perpetuating cycles of abuse and violence on partners that he gets into it with, but by the end, there is kind of a resolution. It starts with him getting attacked in this cave. He loses his memory and has uncontrollable anger and violence patterns he can’t break, so that’s kind of the theme for these first issues, to try and come back to the history and own it. I just drew two more issues of Gaylord last year. It was a surprise. I just pooped them out like an egg or something. They take awhile to draw, but number seven and number eight happened very fluidly, almost writing themselves.

JG: The phoenix metaphor is intentional?

Yeah. As the comic started, it was amorphous, but a phoenix is a really goofy and great way for me to go through all these adventures. It was a nice, mythical entity constantly being reborn through fire, coming out fresh.

OA: Congratulations on Gaylord Phoenix, as well as several of your self-published comic zines like Rico McTaco and Esoteric Erotics being in the MoMA’s archival library collection, as well as the compilation of Gaylor Phoenix comics published by Secret Acres, not to mention an IGNATZ Award for most outstanding graphic novel!

Yeah! It was a pretty big award to win and it was a big surprise because more and more graphic novels come out each year, so it was like… this weird one won? It starts off real scrappy because I was learning what was interesting to draw while I was doing it. Even though it’s an indy award and no competition for Marvel, it’s very cool.

JG: To put a lot of your personal stuff out there and be acknowledged on any level means you are doing something right.

I’ve always felt really engaged and embraced by indy comics and zines. I always loved what I picked up as a teenager as far as comics and zines, so I feel like it forced me to bring my A-game when I started making them. It is such a culture of small objects, easy to trade and a great way to exchange ideas.

JG: What is it about zines that make them so darn desirable?

I thought about this a lot when I worked at a zine store. Why? It is nice to have an intentional physical object. Having grown up with books, I love having them around partially because of the physicality. I can’t pull it up on my phone, but I can have a more intimate experience. Gaylord Phoenix was my main artistic practice for a while, but after doing several issues, I realized I couldn’t convey what I wanted because what I was thinking about was less narrative and more idea based. That’s when I started drawing buildings.

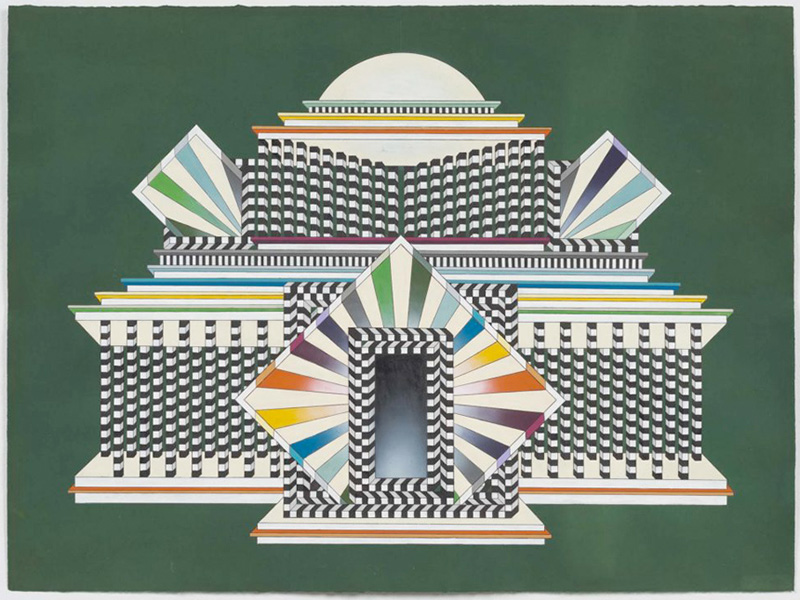

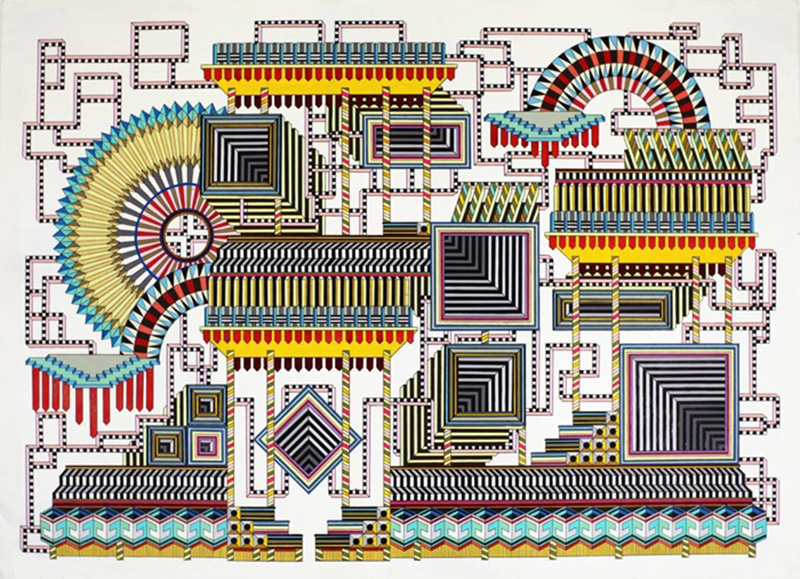

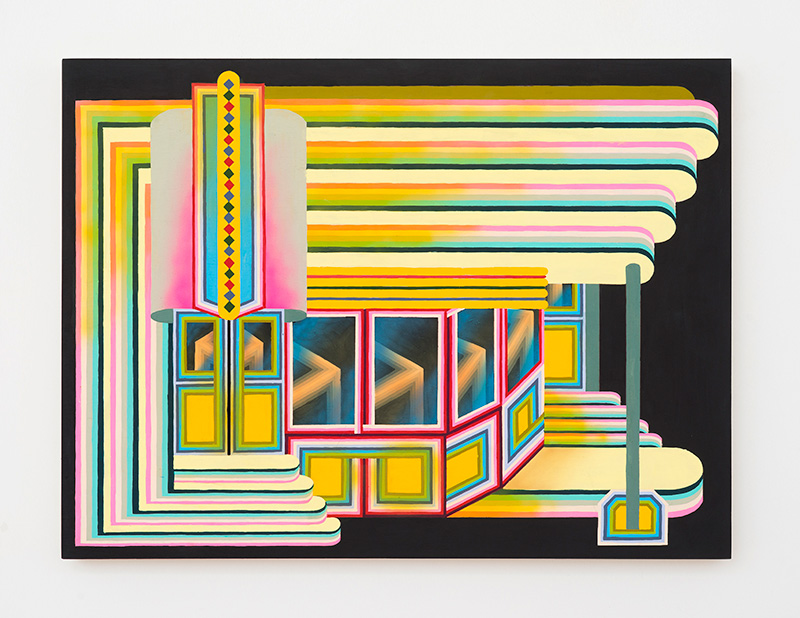

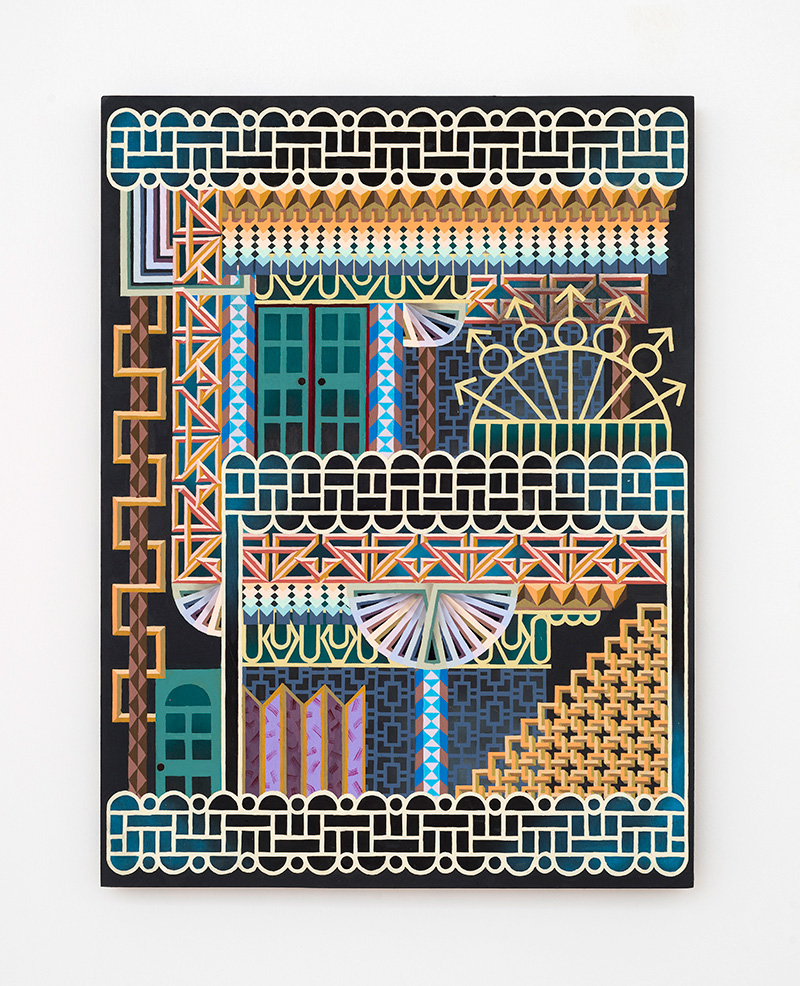

JG: You have a lot of artwork based around architecture and the body as a building or structure.

There have been strange and ecstatic depictions of the body throughout art history, like Forrest Bess, that I want to echo. Thinking of the body as a building is very easy for me to do. The queerness is in the nitty-gritty construction. I think the interesting thing to think about buildings and architecture is that they are really just shells for people to occupy and it’s impossible to assign a gender to that.

JG: Good point. Memory Palaces is a series of LGBTQ buildings, like bathhouses and bars. Did they exist or were they imagined?

Memory Palaces was a mix of things. A couple of buildings were based on empty spaces around Chicago that already looked like a ready-made queer space, and I figured I wanted to composite and draw that because it is a space I would want to have. A lot of them were spaces that existed once as a queer space but don’t exist anymore and are reimagined. It’s always been about tapping into knowing that these things existed as a source of power in the future versus a nostalgia trip. Less “Boo hoo, that doesn’t exist anymore,” and more like, “We have agency in the present to create a world.”

JG: Do you feel that is working?

Yes, in some ways, and in other ways, it’s a constant project. It’s hard to say that anything is working these days.

JG: I wrote this down when I saw your slideshow a while back: “Gender that can change opens up and doesn’t work closed off.”

Totally. That relates to the more fortress-y work where I was making drawings related to limitation and validation. There was this drawing called Personal Business that was based around structures in Chicago and Los Angeles where you see a very dumpy wall hiding a pretty fabulous thing. I think, in Chicago, there was a private social club that concealed a secret garden in the back. It’s like, you have this severe filter of who gets to see this fabulous interior of you. There is something behind it that is pretty fabulous, but there’s no access, and that’s just part of trans identity. Today, I’m pretty open in my work, but I’m definitely not at the grocery store being like, “I’m Traaaaans!” I think people aren’t safe being public about that stuff, although I would want a world where people are being acknowledged and celebrated.

JG: Are there self-imposed rules to your work such as how and why you make certain structures, patterns, and grids?

There is a point where the rules don’t serve you. I’ll come up with an idea within the framework of the rules, but for a while, I was getting really uptight about whether this drawing was an accurate building and then I was, like, “IT’S A DRAWING!” It doesn’t have to look like any building on the planet and people don’t need to recognize it as a building at all. It’s an ecstatic drawing of space and bodies. I feel like the rules can really tie me up if I don’t have the desire to mess with them. I don’t feel flat out motivated to draw buildings. I use drawing and painting as a thinking process to work stuff out in my mind. I start with a scrambled egg of an idea where this building was a place, and it feels like trying to rope in visual ways to convey both a feeling and idea. It feels like creating a beautiful riddle, a space to hold ideas. It’s now a building in the loosest sense and a grid in name only. When a picture starts to vibrate it’s, “Oh, you are telling me something… like, hands off.” If it didn’t, I’d work on it forever.

JG: What are you making now?

I’m working on chest drawings now. One is called Double Keyhole, which is the type of chest surgery that I had. I was looking at keyhole forms in architecture and tapping into the feeling of being put under for surgery. It was like an out-of-body experience. I’m trying to get into that.

JG: That’s why it’s a cathedral?

I grew up in a really strict Catholic household with lots of churchy shit to get through and over. That was in my childhood, so these Polish church structures are coming back around in this series.

JG: Before you had the surgery, were you miserable, or was everything ok?

I was ok. I’ve definitely experienced body dysphoria, but also, as a trans person, had the experience of trying to appreciate my body for what it is. My gender identity is what it is. I was raised as a girl who recognized there was something trans and queer in my identity but didn’t have a name for it.

My access to medical care has been scraggly around the edges. If chest surgery can happen, that’s a lucky break, or I get access to hormones, and that’s a lucky break. If I don’t pass as a man in the world, that’s fine. It’s all the puzzles of a non-binary gender and I am one. At the same time, it breaks down to binary. My journey into any kind of transition has never been about passing and never been fast. My body doesn’t respond that way. It’s complicated.

With an assigned female body and transitioning to male, I think part of it has always been to make sure it wasn’t rooted in misogyny. Making sure I was true to my own feelings about myself and not like thinking it would be easier to just get with the patriarchy or something wack like that. It was never that blatant. Just working through loving my body, even if I had breasts, and loving it no matter how it looked and owning my identity within that.

JG: As a kid, were you alone a lot, or did you always have friends?

In high school, my closest friends were girls but also weirdos. It never really mattered to me, but I did gravitate toward people who I felt would be open to that. I was also really into learning things in high school and obviously dressed cool because I got the worst dressed award.

JG: Having been through chest surgery, can you talk about healing and coming back into a new life? Does it feel, for lack of a better term, “right”?

It feels like the right decision. Recovery was very strange. My whole chest was numb. The first sensation I was able to detect was weird because I knew what having my chest touched felt like, but it was this new sensation coupled with the memory of what I knew the sensation felt like. It kind of merged onto a whole new feeling. Having no sensation in my chest was like waking up in a new altered body. I’m still myself but in a new transformed body.

OA: Like new mental and literal feelings were separated for a while?

Exactly. It was exciting but it was really a lesson of being in a non-binary body in the world now too. The surgery was in 2005 and was like, “Ahh, I have transitioned!” But people would still say, “What’s she up to?” which I don’t mind. It was interesting to have a masculinized chest but still be myself. There was not an instant switch like, “Now you’re on the other side of the binary.”

But one day, this past October, I was at a music festival where everyone was saying, “Thanks, dude,” and for me it was, “Whaaat is this world?” I had to get my computer fixed and the guys at the computer store were like, “Here’s what’s up, Bro,” and I thought, “Are you kidding me? I’m a Bro?!” I was aghast [laughs]. It was like, “Oh no, too far!” So, yeah, all of a sudden I’ve become a full-on Bro. There is something about it that feels very new and exciting, but there’s also, whoa, if I am passing as a man, I am much more aware of taking up a lot of man space, ha ha. It’s still fresh.

JG: I would think growing up knowing you are queer and finally getting to become the truth of who you are, would feel not new. Or is that naive?

There is something that does feel like a relief. But that’s not even the right word. It’s a wild social shift that’s happening in my life. Passing as this, not that. Also being honest about trans identity has always been core to me and my work, and I feel that passing more as a man is not that simple. There is a relief to being seen in that way, but the biggest relief is being seen and feeling safe as a trans man. That feels the most honest.

@ediefake